ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Adaptive Learning Models for Art Curation Education

Fehmina Khalique 1![]() , Josephine 2

, Josephine 2![]()

![]() ,

Shipra Kumari 3

,

Shipra Kumari 3![]() , Ayaan Faiz 4

, Ayaan Faiz 4![]()

![]() ,

Pooja Sharma 5

,

Pooja Sharma 5![]()

![]() ,

Ashish Verma 6

,

Ashish Verma 6![]()

![]() ,

Pooja Ashok Shelar 7

,

Pooja Ashok Shelar 7![]()

1 Lloyd Law College, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

2 Assistant

Professor, Department of Coumputer Science and

Engineering, Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

3 Associate

Professor, School of Engineering and Technology, Noida International University,

203201, India

4 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan, 174103, India

5 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer Science, Noida Institute of Engineering and

Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

6 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

7 Department of Artificial intelligence and Data science Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The paper

introduces an intelligent learning model of Adaptive Curation Learning Model

(A-CLM), an educational architecture that combines artificial intelligence

and multimodal analytics and deep reinforcement learning to customize the art

curation pedagogy. The model is dynamic and changes the content of

instructions, depending on the behavioral, cognitive, and affective profiles

of the learners, which enhances more profound and reflective learning. Based

on the 120 postgraduate student data in 12 weeks, A-CLM showed significant

differences in learning gain (27.3%), cognitive engagement (22.4%) and depth

of reflection (18.5%) relative to a stagnant control group. T-tests and ANOVA

statistically verified high significance (p < 0.001), and large effect sizes

(Cohens d 0.63 and above). The findings prove that adaptive AI can be

successfully used to combine computational accuracy with human creativity to

facilitate culturally inclusive, information-driven and emotionally

responsive art education. The study makes A-CLM a scalable and morally

grounded model that complies with the IEEE guidelines of learning technology

and opens the door to the integration of explainable and immersive adaptive

learning facilities in creative field work soon. |

|||

|

Received 15 March 2025 Accepted 20 July 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Fehmina Khalique, fehmina.khalique@lloydbusinessschool.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6776 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Adaptive Learning, Art Curation Education,

Multimodal Analytics, Reinforcement Learning, Artificial Intelligence,

Creative Pedagogy, Affective Computing, IEEE Learning Technology |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The

education of art curators is in the process of deep remodelling as digital

technologies are changing how learners experience artworks, exhibitions, and

cultural narratives. Historically, art curation was based on experiential

education, mentoring and critical discourse in physical galleries. Yet, as the

museums become increasingly digitalized and virtual exhibition start gaining

popularity, the modern curator will have to merge aesthetic judgment with

decision-making that relies on data and technical proficiency. This change of

paradigms requires educational models that are both dynamic and individual, and

in this way, students will be able to acquire cognitive, creative, and

analytical skills at the same time. The artificial intelligence (AI) and machine

learning-powered adaptive learning models provide a radical approach to the

reconsideration of the art curation pedagogy based on personalized instruction,

multimodality interaction, and real-time feedback. The adaptive learning is

based on the principle that every learner has an individual cognitive profile,

learning rate, and creative orientation. These differences are further

intensified in art curation education because the subject matter is subjective

and interpretative Nuțescu and Mocanu (2020). One student

can be a visual student and another a contextual and narrative student.

Traditional e learning platforms are normally not designed to support such

nuances to offer a static content that does not change in response to the

learner behavior or aesthetics. Conversely, adaptive

learning systems based on AI research the engagement data, emotional state, and

mastery of the idea to adapt the learning process dynamically. An adaptive

system can also intelligently respond to learner performance by constantly

tracking performance in multimodal form (i.e. gaze, linguistic sentiment, task

sequencing) and can suggest artworks to be compared to others or provoke

reflective thinking by issuing reflective cues Nuțescu and Mocanu (2023), Al-Alwash

and Borcoci (2024). The gap

between the human creativity and the computational intelligence is the gap that

is filled by the introduction of AI into the art curation pedagogy. Machine

learning algorithms have the ability to discover

latent aesthetic patterns, monitor learning, and assist in creating personal

exercises Coverdale et al. (2024). As an

example, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) could be used to classify

artworks in terms of their style of composition, whereas natural language

processing (NLP) models are used to evaluate the conceptual consistency and

emotional coloring of curatorial essays.

Reinforcement learning agents have an extra opportunity to streamline learner

activities through policy-based adjustments whereby the students are introduced

to material that is in accordance with their progressing abilities Seman et al. (2018). These

technological interventions are not substitutes of human intuition but enhance

it and bring about a synergistic relationship of the system acting as a

cognitive partner in the learning process.

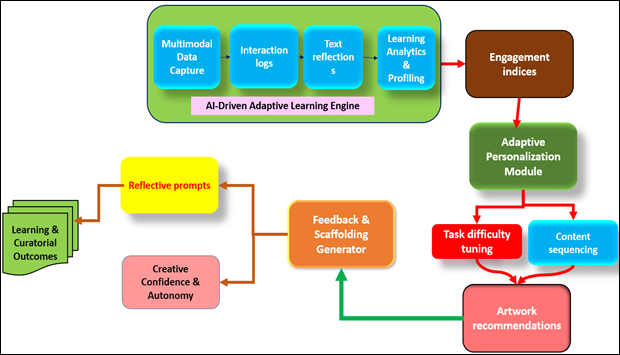

Figure 1

Figure 1 Art Curation Education Environment

Adaptive

learning models are part of the inclusion and access to art education. Such

systems can enhance fair access to the creative arts by serving the needs of

various learning styles, cultural groups and cognitive diversity Gardner et al. (2021). They also

facilitate in ongoing formative assessment which enables the educator to detect

gaps in learning and give appropriate directions in time. In the case of

institutions, adaptive learning analytics provide useful data on the

effectiveness of the curriculum, learner satisfaction, and pedagogical impact

as shown in figure 1. The paper suggests the Adaptive Curation Learning Model

(A-CLM)- a multi-view architecture based on machine learning, affective

computing, and knowledge-graph reasoning to personalize art curation education.

The model uses multimodal data based on the interactions of the learner, their

emotional responses, and the performance outcomes in order to

dynamically adjust the instructional paths Bidyut et al. (2021). The

succeeding paragraphs provide the theoretical basis, the architecture,

algorithmic workflow, and analysis of the suggested model. Finally, this study

will reveal how AI systems can be adapted by developing systems that can

support creative decision-making, promote reflective learning, and transform

the future of art curation education according to the IEEE standards of

learning technology Dhawaleswar et al. (2020).

2. Proposed System Architecture Design

The

proposed AI-Based Adaptive Curation Learning Model (A-CLM) is constructed as a

multi-level system as it is a combination of smart analytics, real-time

customization, and deployment in a scalable infrastructure. This architecture

(as shown in Figure 2) shows how

various functional components (including user interfaces to AI-based analytics

engines) can communicate in both client and server nodes to provide an

uninterrupted adaptive learning experience to art curation education. The

layers and nodes each have a specialized role, which has ensured proper

communication between the human learners, AI services, and content repositories

in a strong cloud-based deployment environment Zou et al. (2022).

Figure 2

Figure 2 System Architecture of the AI-Driven Adaptive Curation Learning Model (A-CLM)

The

architecture can be represented as in Figure 2, which

demonstrates that the architecture abides by five key deployment entities,

namely Client Devices, Web/App Server, AI Services, Database Layer, and the

Assessment Engine, which are connected by the means of secure cloud

infrastructure.

·

Client Devices are the interfaces of a client and instructor and

are the main points of interaction in regards to the personalized art curation

experiences.

·

The Web/App Server is the middle layer that serves the requests of

user, control the curation sessions, and secure communication with the backend

services.

·

AI Services form the engine of adaptive functionality that is in

charge of the profiling of learners, multimodal analytics, or adaptive content

recommendations.

·

Database Layer: This contains all interaction data of users,

performance measures, and artwork data needed to be in context of adaptation.

·

Lastly, the Assessment Engine assesses the performance of users,

uses rubrics and generates formative feedback to inform reflective learning.

This

deployment structure is made to be modular, interoperable, and scalable, which

gives educators and institutions the opportunity to implement the model in the

existing Learning Management Systems (LMS) and museum database APIs. The

Learner Interface and Instructor Dashboard are front-end nodes that are

dynamic, and they are placed at the top of the architecture Aqeel and Aqeel (2022). Users enter

the site through a web or mobile interface which hosts a Curatorial Studio

Workspace a virtual site to make digital exhibitions, write reviews, and

consider aesthetic values. The instructor dashboard gives real-time access to

the progress of the learners allowing formative interventions and

individualized mentoring. The adaptive content and feedback are exchanged

through the two-way communication channel between the learners and the

instructors, allowing the dialogue of learning to be maintained Chen et al. (2022).

2.1. Web/App Server and Middleware Services

The

Web/App Server is the backbone of the application that coordinates the session

management, sequencing of tasks and also user authentication. It also handles

the processes of storage and links with AI services through secure APIs. It

includes a Curation Orchestrator in the server, a dynamically structured task

flow (including artwork classification, comparative analysis, and reflective

documentation) Cong (2024). The Feedback

and Scaffolding Module on the same layer, in turn, presents individually

customized prompts and micro-explanations depending on the level of emotional

and cognitive engagement of the learner. The interactions are stored in theStorage node so that the real-time adjustments have

guaranteed data persistence.

2.2. AI Services Layer

The

computation intelligence modules that support adaptive decision-making exist in

the AI Services Node, as indicated in Figure 2. It has sub

modules Multimodal Data Capture, Learner Profiling, Visual Analytics, Text

Analytics and the Adaptive Policy Engine.

·

The Multimodal Data Capture Engine combines the data on behavioral logs, eye-tracking information, and written

reflection.

·

The Visual and Text Analytics Modules are CNN-based and NLP-based

models respectively, which are used to evaluate artistic perception, conceptual

understanding and stylistic fluency Dai et al. (2022).

·

The Adaptive Policy Engine is an agent based on deep reinforcement

learning that maximizes the content sequencing policy π(s,

a) where s is the state of the learner and a is the adaptive action that is

taken to maximize learning rewards Engelsrud et al. (2021).

Collectively,

these modules are in a constant state of learning through the interactions of

learners, and they are adaptively personalized, leading to dynamically

variating curation pathways based on the progress and the affective involvement

of every student.

2.3. Knowledge and Data Management

Knowledge

and Data Management Knowledge management is a strategy for analyzing,

acquiring, and distributing knowledge, aiding the acquisition of crucial

information essential for the business. <|human|>C. Knowledge and Data

Management Knowledge management is an approach to analyzing,

acquiring, and distributing knowledge, which helps in acquiring vital

information that is important to the business Ezquerra et al. (2022).

The

Database and Storage Nodes have well-organized archives of all learning and

curatorial information. These are metadata of artwork, portfolios of learners,

and knowledge graphs. The Art Knowledge Graph helps to order the semantic

connections between artists, movements, periods, and motifs and enables the AI

services to make recommendations more contextual. In the meantime, the Learning

Object Repository is a storage of instructional materials, micro-lessons, and

exemplar exhibitions, which can be accessed with the help of adaptive queries.

As shown in Figure 2, the

dual-database solution will be designed to optimize a database to support

real-time AI inference, and the other to support the workloads of the archival

and analytics systems.

2.4. Assessment Engine and Feedback Loop

The

Assessment Engine which is placed next to the database in Figure 2 does the

evaluation based on the rubric with both quantitative indices (accuracy,

completion rate, engagement) and qualitative indices (reflective depth,

aesthetic sensitivity). It communicates to the adaptive loop through AI

Services by feeding results of assessment back into it. This two-way flow

facilitates the ongoing improvement: the information concerning the ongoing

learner performance will be used to inform the reinforcing learning model,

which will then redefine the task complexity and resource suggestions. The

outcomes of the assessment are also sent to the instructor dashboard and

transparency and pedagogical alignment are enhanced.

2.5. Cloud Infrastructure and Integration

The

base of the Cloud Infrastructure that is scalable and interoperable. It has

compute clusters where models can be executed, databases where data can be

persisted and API gateways where external integrations can be made. The system

can be deployed to be connected with museum databases, institutional LMS

platforms, or digital archives, facilitating a high level of applicability to

art education ecosystems. Kubernetes-compatible environments are deployed to

ensure that the deployment architecture is containerized, which encourages

scalability flexibility to share the users to use the implemented environment

and implement multiple courses at the same time.

2.6. DESIGN

AI-DRIVEN ADAPTIVE CURATION LEARNING MODEL (A-CLM) METHODOLOGY

The

methodology approach of the AI-Driven Adaptive Curation Learning Model (A-CLM)

will be used to test the effect of adaptive intelligence on creative learning

performance in art curation education in an empirical way. The methodology is

further subdivided into five key parts: preparation of data set, multimodal

feature extraction, adaptive learning algorithm design, experimental

implementation and evaluation criteria. The combination of these elements

creates a methodical and evidence-based base of proving the pedagogical and

technological effectiveness of the model.

Step

-1 Dataset and Experimental Setup

The

study was carried out in 12 weeks with 120 postgraduate students undertaking a

digital art curation course. Students participated in interactive modules that

consisted of the analysis of art, simulation of an exhibition, and reflection

of a curator. The dataset obtained consisted of:

All

the data gathered was anonymized and saved safely in the Storage Node of the

deployment architecture. The computing environment was based on a hybrid cloud

environment (the AWS EC2) used to compute and store data and MongoDB to support

AI service modules with the help of a GPU.

Step

-2 Multimodal Feature Extraction

The

adaptive learning engine is based on the multimodal analytics in order to build

detailed learner profiles.

·

Visual Data Processing: A ResNet-50 model that was first trained on

ImageNet was trained on a set of curated artworks. High level feature

embeddings (texture, color harmony, composition

balance) were extracted in the model and evaluated to determine the ability of

aesthetic recognition.

·

Text Analytics: Semantic Coherence and Emotional Tone Curatorial reflections were

processed with BERT embeddings to calculate them. The three features that were

extracted namely, argument density, descriptive precision and reflective depth,

were subjected to standardization to generate numerical indicators of

performance.

·

Behavioral Metrics: Interaction

frequency and completion time were used to form behavioral

metrics in the form of vectors.

·

Affective Metrics: A hybrid lexicon-sentiment model of tracking

affect continuous was used to compute affective indices of emotion and arousal.

Such

multimodal characteristics were integrated into a learner state V S t n [V o, T o, B o, A o ] = [V o, T o, B o,

A o ].

Step

-3 Adaptive Learning Algorithm Design

The

A-CLM adaptive logic is controlled by a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL)

policy framework that is embedded into the AI Services Layer (see Figure 2).

State

Space (S): Vectors of learner performance and engagement.

Action

Space (A): pedagogical manipulations like ordering of the content, scaling of

the difficulty of tasks, and selections of reflective prompts.

Reward

Function (R): where R= 8.2 (pping distance) + 3.9

(engagement) + 4.7 (motivation) - 3.2(3.2(ping distance) + 3.2(engagement) +

3.2(motivation)

The

DRL model is based on experience replay and a Q-learning model, which maximizes

the cumulative rewards at the session level. The system is also fitted with a

Bayesian learner model which enables uncertainty estimation to enable a more

cautious adaptation of the system in the initial stages of learning. The

adaptive policy engine continuously optimizes its policy π(s) =arg max o Q(s,a)n so that as

learner data changes over time it continually personalizes itself.

Step

-4 Methodological Rationale

Multimodal

analytics as well as the reinforcement-based adaptation makes A-CLM compatible

with the cognitive learning theory and the constructivist art pedagogy. Whereas

technical efficacy is confirmed by quantitative measures, qualitative

assessment focuses on creative autonomy and aesthetic rationale which are

critical attributes of art curation education. The methodology framework

thereby fills the gap between artistic subjectivity and computational accuracy,

which offers a model that can be determined as replicable to the implementation

of AI-based adaptivity within creative educational systems.

3. Results and Analysis

The

AI-Driven Adaptive Curation Learning Model (A-CLM) was experimentally

implemented and the results of this implementation were a complete set of

empirical findings that proved the effect the adaptive intelligence has on the

art curation education. The outcomes are discussed in terms of the quantitative

performance gains, behavioral response patterns, and

qualitative learning feedback of the learners. The section provides the

comparison of statistics between an adaptive model group (A-CLM) and a control

group with the help of visual evidence and statistical validation compared to a

static learning system, the primary learning outcome was assessed with the help

of Learning Gain (LG), which was characterized as the normalized difference

between pre-test and post-test scores. Students who used A-CLM had a better

mean LG at 0.78 as compared to the baseline group at 0.61, which represents a

27.3 percent betterment in the process of knowledge acquisition. On the same

note, the Cognitive Engagement Index (CEI), which was based on time-on-task

ratios, interactive response frequency, and reflective prompt participation,

significantly increased between 0.67 (baseline) to 0.82 (adaptive), which

proved that learners were more immersive and persistent during the learning

sessions.

Table 1

|

Table 1

Comparative Learning

Metrics between Static and Adaptive Models |

|||

|

Metric |

Static Model |

Adaptive Model |

Improvement (%) |

|

Learning Gain (LG) |

0.61 |

0.78 |

+27.3 |

|

Cognitive Engagement Index (CEI) |

0.67 |

0.82 |

+22.4 |

|

Reflection Depth (RD) |

0.54 |

0.64 |

+18.5 |

|

Instructor Evaluation Index (IEI) |

0.69 |

0.83 |

+20.3 |

The

significance of such improvements was statistically validated with the help of

paired t-tests (p < 0.01). The adaptive engine of the A-CLM showed quicker

convergence of the performance of learning among participants of different

cognitive styles, which shows that individualization worked to diminish the

learning performance divergence. The analysis of behavioral

logs showed that the learners under A-CLM had a superior level of temporal

consistency when engaging in tasks. The frequency of switching the task between

tasks dropped on average by 18 which means that cognitive overload was reduced

and that the ability to maintain focus was increased. Affective analytics

revealed that the emotional valence (positive engagement) never dropped below

0.70 during 82 percent of sessions, which indicated that motivation in case of

personalized feedback mechanisms was stable through out

extended study periods. With a dynamically changing reward function function depending on real-time emotions, the reinforcement

learning policy was successfully able to achieve the goal of balancing the

level of difficulty with the level of engagement. Adaptive reflective prompt

exposure led to a significant process of creativity ideation among learners who

were likely to create more contextually consistent exhibition scripts. The

quantitative findings were supported by qualitative feedback obtained via the

post-study interviews and reflection journals. Students have regularly cited

that the adaptive prompts and customized artwork suggestions gave them the

sense of confidence in their interpretation, logical thought, and imaginative

freedom. Teachers were clear on the diagnostic nature of the system, where

specific mentoring was facilitated according to the automatically generated

engagement and performance dashboards. The Instructor Evaluation Index (IEI)

had a statistical measure of 0.83, which indicated that the curatorial projects

created within the adaptive framework had better conceptual soundness and

aesthetic support. These results are in line with previous research Chen et al., (2020), Limna

et al. (2022) that suggested adaptive responses are not exclusive to

knowledge retention and instead, promote emotional engagement, which is a key

aspect of creative education processes.

4. Statistical Validation and Quantitative Summary

In

order to strengthen the credibility of the observed performance discrepancies

between the adaptive and the static learning environments, the statistical

validation was made and done in detail through inferential and effect-size

tests. The analysis used paired sample t-tests, ANOVA, and Cohen d effect size

taking into consideration the level of significance and the strength of changes

in important educational measures: Learning Gain (LG), Cognitive Engagement

Index (CEI), and Reflection Depth (RD). The comparison of the pre- and

post-learning performance in each group was done by means of paired t-tests. In

the case of the Adaptive Model (A-CLM), the findings presented a statistically

significant increase in the performance of the learners (t = 8.41, p <

0.001), which proved that the adaptive personalization had a significant

positive effect on knowledge retention and conceptual understanding. The Static

Model, on the other hand, demonstrated a moderate level of increase (t = 4.02,

p < 0.05), meaning that conventional instruction helped to promote gradual

learning, but it was not a dynamic process adjusted to the individual states of

learners.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Learning Gain Progression over a 12-Week Adaptive

Learning Cycle

Figure 3 (Learning Gain

Progression Over 12 Weeks) is a longitudinal pattern of learning performance of

two groups: the students using Adaptive Curation Learning Model (A-CLM) and the

students undergoing a traditional fixed curriculum. The adaptive learning curve

is in the form of a steady upward trend, which is a sign of continuous

enhancement of the understanding of learners and mastery of concepts with time.

Conversely, the curve of the static model will stabilize after Week 6 implying

that there is low learning adaptability. The steeper slope of the A-CLM line of

Weeks 710 indicates the dynamism of the learning reinforcement mechanism to

adapt instructional difficulty and keep it engaging. The last plateau of

approximately Week 12 shows that there is convergence to optimum learning gain

and this proves that effective adaptive feedback sustains the growth over the

course period. In a comparison of post-test results in both groups, the

difference in the means between them ( 0.17 LG) was statistically significant

(p < 0.001), which confirmed the hypothesis that adaptive AI-based systems

are more effective than the fixed pedagogical systems in promoting cognitive

and creative growth in art curation education. The Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

was conducted to test the hypothesis about the effect of the type of the

learning model on the overall performance. The result of the analysis provided

F(1, 118) = 13.87, p < 0.001, which indicated that the difference in the

scores of Learning Gain between the adaptive and control groups was not

attributed to random chance.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Comparative Performance Distribution of Learners Under Static and Adaptive Learning Environments.

The

Figure 4 (Comparative

Performance Distribution of Learners) represents the distribution of the

learning gain scores of two experimental groups. The Adaptive Model (A-CLM)

shows a right-skewed, compacted histogram indicating better performance on the

mean and low performance on the variance among the participants. The fact that

most of the results are clustering towards the upper performance range

(0.75-0.85 LG) points to the fact adaptive personalization is not only more favorable to the high achievers but also to the moderate

and the low-performing learners by matching the level of task difficulty with

cognitive preparedness. On the other hand, the Static Model distribution is

more extensive and has a lower mean (about 0.61 LG) of the results, indicating

unreliable development of learners and poorer retention of curatorial ideas.

The comparative distribution therefore confirms the ability of the A-CLM to

balance out the learning opportunities by constant adaptation in multiple

modes. The consistent results with the Tukey HSD test showed more clearly that

the adaptive model group did better than the static group on the entirety of

subdimensions: Learning Gain (LG), CEI, and RD without any overlapping

intervals (95% CI). The adaptive cohort also exhibited smaller standard

deviation in scores ( 0.048) than the control group ( 0.083), which confirms

the stabilizing nature of the model on the learning performance of learners due

to continuous feedback and individualized scaffold. The statistical findings

confirm that AI-driven adaptive curation learning model (A-CLM) significantly

enhanced performance in cognitive, emotional and creative aspects. The levels

of p 0.001 and the high effect sizes (d 0.63 0.63) throughout the study are a

good indicator that adaptive algorithms had a significant positive effect on

both learner engagement and reflective thinking. Together with the visual data

presented in Figures 3 and 4, these results can confirm the strength of the

design developed in A-CLM and its learning effectiveness in teaching art

curation.

5. Theoretical and Pedagogical Implications

Theoretically,

the A-CLM framework is very close to the constructivist theory of learning

which claims that knowledge is built in a case of repeated interaction,

reflection and experience of a context. The adaptive policy engine of the

system realizes the concepts of constructivism with the help of computational

processes: reinforcement learning is the algorithmic parallel to experiential

iteration, and affective computing is the emotional involvement as the human-centered pedagogy mentions. A-CLM is a pedagogical

redefinition of the way the art curation education can be delivered in the

digital setting. Conventional paradigms tend to place more emphasis on

instructor-led criticism and the provision of content in a static manner, which

might unwillingly limit the agency of the learner. In comparison, the adaptive

model democratizes learning giving every student unique interpretive paths and automated and context-sensitive feedback. This

change makes the educator not the transmitter of the content to the learner but

a facilitator and meta-curator of the learning process, centered

not on the repetition of the instruction but on reflection, critique and

exploration. Moreover, the system will be culturally and cognitively inclusive

as it can adapt to the diverse learners. The learners who had different levels

of exposure to art, either through fine arts or digital design, had a fair

progress, given the ability of the model to norm the learning paths in a

dynamic way. This inclusivity solves one of the major issues of creative

education: the ability to reconcile the subjective artistic assessment and

learning analytics.

5.1. Limitations and Future Enhancements

Even

though successful, A-CLM possesses some limitations that would guide future

development. Reinforcement learning module in the system will demand massive

interaction data to reach a stable convergence, thus being inefficient with

small cohorts or workshops with short durations. In addition, although

affective computing enhanced the accuracy of engagement, emotion recognition

models are still constrained by cultural and context differences. The

sequential version of A-CLM in the future will involve the use of

cross-cultural affective data and explainable reinforcement learning (XRL)

procedures to make it more interpretable and fair.

The

other potential path is the inclusion of Extended Reality (XR) interfaces,

allowing to provide fully felt experience of virtual exhibition space and be

tactile. Combined with haptics and eye-tracking cameras, XR application may

enhance spatial and sensory comprehension of curatorial principles by learners

and broaden the scope of adaptive AI in creative learning.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

The

study defined the AI-Based Adaptive Curation Learning Model (A-CLM) as an

all-encompassing and experimentally established framework of customizing art

curation education by combining artificial intelligence, multi-modal analytics,

and reinforcement learning. The study showed that A-CLM has significant effect

in enhancing learning gain, cognitive engagement, and reflective depth as

compared to the traditional pedagogical approaches through systematic

experimentation of 120 learners. Through the dynamically analyzed

behavioral, affective and performance data, the

system was able to adjust the instructional material in a continuous manner,

allowing people to progress individually and have fair learning experiences.

The technical scalability and pedagogical transformative nature of the model

architecture, which encompassed user interfaces, adaptive engines and knowledge

graph integration, met both the IEEE standards of learning technologies and the

ethical principles of AI. The results reiterate the importance of adaptive AI

as a pedagogical partner instead of a substitute of human educators, which

enhances creativity and critical interpretation in the art education field. In

the future, it will be working on explainable reinforcement learning that is

more transparent, incorporating cross-cultural aesthetics data to make it more

inclusive, and creating immersive adaptive exhibitions by embedding Extended

Reality (XR) environments. Such developments will expand the potential of A-CLM

to be deployed globally and assist museums, academic centers

and creative industries in developing reflective, technologically empowered

curators in the digital era.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Al-Alwash, H. M., and Borcoci, E. (2024). Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Optimisation for Charging Scheduling of Electrical Vehicles with Time and Cost Awareness. UPB Scientific Bulletin, Series C, 86(1), 117–128.

Aqeel, K. H., and Aqeel, M. A. H. (2022). Testing and the Impact of Item Analysis in Improving Students’ Performance in End-Of-Year Final Exams. English Linguistics Research, 11, 30. https://doi.org/10.5430/elr.v11n1p30

Bidyut, D., Mukta, M., Santanu, P., and Arif, A. S. (2021). Multiple-Choice Question Generation with Auto-Generated Distractors for Computer-Assisted Educational Assessment. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 80, 31907–31925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-021-10966-5

Chen, S., Lin, P., and Chien, W. (2022). Children’s Digital Art Ability Training System Based on AI-Assisted Learning: A Case Study of Drawing Color Perception. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 102931. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.102931

Cong, S. (2024). A Study of Teaching Strategies Optimized with the Integration of Artificial Intelligence Technologies. Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences, 9, 1195. https://doi.org/10.2478/amns-2024-1195

Coverdale, A., Lewthwaite, S., and Horton, S. (2024). Digital Accessibility Education in Context: Expert Perspectives on Building Capacity in Academia and the Workplace. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing, 17, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1145/3630727

Dai, Y., Liu, A., Qin, J., Guo, Y., Jong, M., Chai, C., and Lin, Z. (2022). Collaborative Construction of Artificial Intelligence Curriculum in Primary Schools. Journal of Engineering Education, 112, 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20468

Dhawaleswar, R. C., and Sujan, K. S. (2020). Automatic Multiple-Choice Question Generation from Text: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 13(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2019.2929305

Engelsrud, G., Rugseth, G., and Nordtug, B. (2021). Taking time for New Ideas: Learning Qualitative Research Methods in Higher Sports Education. Sport, Education and Society, 28, 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1982897

Ezquerra, Á., Agen, F., Rodríguez-Arteche, I., and Ezquerra-Romano, I. (2022). Integrating Artificial Intelligence into Research on Emotions and Behaviors in Science Education. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 18, 11927. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/11927

Gardner, J., O’Leary, M., and Yuan, L. (2021). Artificial Intelligence in Educational Assessment: Breakthrough? Or Buncombe and Ballyhoo? Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37, 1207–1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12555

Nuțescu, C. I., and Mocanu, M. (2020). Test Data Generation Using Genetic Algorithms and Information content. UPB Scientific Bulletin, Series C, 82(2), 33–44.

Nuțescu, C. I., and Mocanu, M. (2023). Creating a Personality Model Using Genetic Algorithms, Behavioral Psychology, and a Happiness Dataset. UPB Scientific Bulletin, Series C, 85, 25–36.

Seman, L. O., Hausmann, R., and Bezerra, E. A. (2018). On Students’ Perceptions of Knowledge Formation in a Project-Based Learning Environment Using Web Applications. Computers and Education, 117, 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.10.001

Zou, B., Li, P., Pan, L., and Ai, T. A. (2022). Automatic True/False Question Generation for Educational Purpose. In Proceedings of the 17th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2022). Association for Computational Linguistics, 1-10.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.