ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Generative Design in 3D Printing Education

Tavishi Limaye 1![]()

![]() ,

Durga Prasad 2

,

Durga Prasad 2![]() , Sourav Rampal 3

, Sourav Rampal 3![]()

![]() ,

Kumaran P 4

,

Kumaran P 4![]()

![]() ,

Vyshnavi A 5

,

Vyshnavi A 5![]()

![]() , Jaspreet

Sidhu 6

, Jaspreet

Sidhu 6![]()

![]() , Pooja Abhijeet Alone7

, Pooja Abhijeet Alone7![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Development Studies, Vivekananda Global University,

Jaipur, India,

2 Associate,

Professor School of Engineering and Technology Noida International University, India

3 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan 174103, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

5 Assistant

Professor, Department of Management Studies, JAIN (Deemed-to-be University),

Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

6 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

7 Department of Engineering, Science and Humanities Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The paper

examines how generative design and 3D printing can be incorporated in the

contemporary design education and how it will enhance the computational

creativity as well as reflective practice and interdisciplinary learning.

This study will apply the design-based mixed-method approach to analysis,

based on the constructivist, constructionist, and experiential theories of

learning, to address whether the use of algorithmic modeling and additive

manufacturing can have an impact on the student learning outcomes. An

implementation framework was developed and executed based on project based modules in which exploration, parametrical

modeling and concrete prototyping were highlighted through iterations.

Quantitative data revealed that the areas of the computational literacy

(↑44.8), creativity (↑48.3) and reflective learning (↑65.4)

changed significantly, but the qualitative data indicated that the engagement

and cognitive flexibility increased. Findings indicate that generative design

brings about a paradigm shift in the sense of following the tools acquisition

to co-create ideas, and technology is considered a proactive partner in the

design thinking. The article also singles out the issues of algorithmic

authorship, data ethics, and accessibility and concludes that adaptive

AI-based and policy-affirmative models of the sustainable implementation of

the curriculum are required. This work of writing contributes to a replicable

model of pedagogy which is a combination of calculation, creativity and

material experimentation; a redefinition of future of design education. |

|||

|

Received 20 March 2025 Accepted 24 July 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Tavishi

Limaye, DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6765 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Generative Design, 3D Printing Pedagogy,

Computational Creativity, Experiential Education, Digital Fabrication,

Reflective Practice, AI-Integrated Curriculum, Educational Innovation |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

As an approach to design based on artificial intelligence

and algorithmic modeling, generative design allows

learners to search huge spaces of solutions by specifying constraints and

performance objectives, but not specifying forms. Applied to the educational

setting, such paradigm promotes experimentation, critical thinking and developing

an imaginative independent thinking, which is one of the fundamental principles

of constructivist and experiential learning theories Wang

et al. (2021)In the learning

process, generative design as part of the 3D printing pedagogy is equivalent to

constructivism by Piaget and constructionism advanced by Papert, both of which

focus on learning by creating and participating. When students iterate the process

of designing, testing and refining physical prototypes created by computational

processes, this makes them the co-creators of new knowledge Mirzaei et al,

Muthumanickam et al (2021). This cyclical process is a resemblance to the Kolb model of

experiential learning wherein tangible experience, contemplative experience,

abstract conceptualization, and experimentation is the cognitive basis of

profound learning. Moreover, since generative design projects are collaborative

and inquiry-based, this aligns with the theory of social learning by Vygotsky

because the students learn through a collective design ecosystem Aman,

B. (2020).

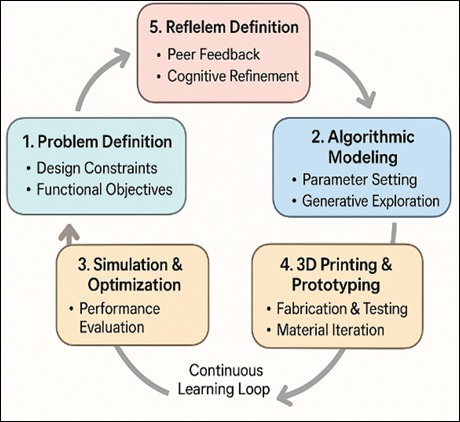

Figure 1

Figure 1 Pedagogical Integration Model for Generative Design and 3D Printing

Curriculum design in its curriculum design approach, the gen-design aspect of 3D printing learning fosters a comprehensive mix of mental, technical, and creative skills. It allows students to balance abstract algorithmic thinking with material-based design thinking, which is, not only the development of computational fluency but also how to critically judge the results of design work in the real world. Problem-based studio projects expose learners to real-world problems, which reflect applicable professional design processes and can facilitate 21 st -century skills like creativity, systems thinking, and adaptability as shown in Figure 1. Finally, the integration of generative design into the educational process reshapes the traditional teacher-centered design into the learner-based, inquisitive one, which enables the students to enlist the power of computation as a creative collaborator Plocher and Panesar (2019).. The paper will explore how this kind of pedagogical integration can drive better learning results, inspiration of innovation and equip the learners with the changing digital design environment.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

The idea of incorporating the concept of generative design into the education of 3D printing is based on the synthesis of constructivist, experiential, and socio-cultural learning paradigms. Such frameworks altogether define the cognitive and pedagogical frame of empowerment of learners to make, think about, and innovate in a computationally guided making Chang et al (2022).It centers on constructivism as defined by Jean Piaget that focuses on making learners active constructors of knowledge through interaction and experience as opposed to being passive receivers of knowledge. When applied to generative design, it would be interpreted as students having conceptual perception as they operate algorithms, parameters, and materials to uncover design opportunities. In its contribution to constructivism, the constructionism proposed by Papert presents the idea that the most efficient way of constructing knowledge is when the learners are occupied with the development of meaningful artifacts Snijder et al (2020). The technologies of generative design and 3D printing are the direct embodiment of this philosophy as they enable the learner to transfer abstract computational logic to the physical world. The cyclic nature of designing, printing, assessing, and red-signing will develop reflection-in-action, which is very similar to the experiential learning cycle of Kolb as the concrete experience and abstract conceptualization interact on a cycle Lu et al. (2024)., Chen et al. (2019). This cycle helps the students to gain meta-cognition about their design choices, which strengthens the attitude of critical and creative thinking. Also, this pedagogical model has a collaborative dimension through the social learning theory proposed by Vygotsky. The peer collaboration, instructed interaction and collective digital depositories in digital fabrication studios creates a zone of proximal development which enhances learning performance.

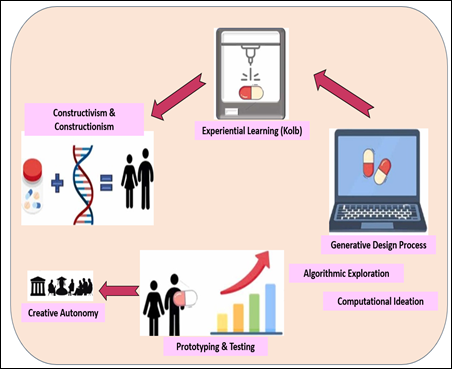

Figure 2

Figure 2 Conceptual Framework Linking Learning Theories with Generative Design Pedagogy

These social engagements allow solving problems together and sharing of approaches to generative modeling, which facilitates individual and group learning paths Yu et al (2019).. The theoretical perspectives explained in this paper are combined to create a cohesive theoretical framework of pedagogical design instruction in generative design as represented in Figure 2. It places generative algorithms and 3D printing processes as mediating technologies that mediate the cognitive development, technical expertise and expressive creativity. Not only does this synthesis create computational literacy, it creates design sensibilities which are needed in modern education to be innovative.

3. Research Methodology

The methodological framework on the study was crafted in such a way that it addresses the research question on how the combination of generative design and 3D printing can impact the learning outcomes, creativity and computational thinking of students involved in design based learning. The study takes a mixed-methods design with a research design being based on both qualitative and quantitative research designs to be able to capture both the quantifiable results as well as the experiential aspects of learning. Such a strategy conforms to the educational research that focuses on refining pedagogical models by means of testing them in real-life classroom settings Vergara Vidal et al (2021).

Step.1 Research Design and Philosophical Orientation

The research has a latent constructivist epistemology which views knowledge as a co-construction due to interactions between the learners and the technology, peers and design activities. The design based research (DBR) framework was chosen because it provides the opportunity to facilitate the cyclic design, enactment, analysis and redesign. The iterations were to determine how generative design tools influence the problem-solving techniques, creativity and reflective learning of the students Zhao et al (2019).

Step.2 Participants and Learning Environment

The sample size was made up of undergraduate students pursuing a digital design and fabrication course as part of an interdisciplinary program of STEAM program. This learning environment was designed as an open innovation studio that was outfitted with 3D printers, CAD software (Fusion 360, Rhino, Grasshopper), and generative design extensions. The students were divided into learning groups so that they could learn and co-create amongst themselves. Reflective discussions and formative assessments were conducted in the stages of design with the help of faculty mentors Aljabali, et al (2024).

Step.3 Data Collection Instruments

Quantitative and qualitative instruments were used in a bid to achieve triangulated evidence. Pre- and post-intervention surveys comprising of design confidence, computational literacy, and creative self-efficacy were used to gather quantitative information. Qualitative data were observation logs, reflective journals and interviews with students about their processes of design and conceptualization Khan and Awan (2018). Digital artifacts were also studied like the design scripts of algorithms and print prototypes to assess the development of design complexity and innovation.

4. Curriculum Design and Implementation Framework

The curriculum design created to combine generative design with 3D printing education was built based on the concepts of experiential, constructivist, and competency-based learning. Its main goal was to make students learn in an active, iterative, and reflective learning environment that enhances computational creativity, material awareness, and interdisciplinary learning. It was created so that the curriculum provides a balance between conceptual knowledge, technical skills, and creative independence in such a way that the students would be holistically involved in both digital and real elements of design.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Curriculum Integration Model for Generative Design and 3D Printing Education

Generative design and 3D printing has become an important research question in the realm of digital and design education that technology has played a role as an aesthetic medium as well as a cognitive scaffold as shown in Figure 3. Early research on the concept of digital fabrication in education focused on the transformational nature of the maker-based learning spaces.

Phase 1] Curriculum Objectives and Learning Outcomes

The curriculum was supposed to bring three outcomes which were supposed to be interrelated:

1) learn algorithmic/computational thinking in the form of parametric models and generative systems;

2) boost the design creativity and innovation through iterative prototyping through 3D printing technologies;

3) encourage critical thinking and group learning on the basis of peer assessment and project research. These goals correspond to some higher-order domains of cognitive thinking developed by Bloom and experiential stages of learning developed by Kolb which focus on reflection and experimentation.

Phase 2] Course Structure and Module Distribution

The course was divided into four consecutive modules:

46 Level: 1 In-depth course: Foundations of Digital Design Thinking Foundations of computational logic, problem framing, and algorithmic creativity.

Location: Generative Design Exploration Module 2: Generative tools (e.g., Fusion 360, Rhino/Grasshopper) Brief overview: Investigations into form-finding and optimization processes through the application of generative tools.

Module 3: The 3D printing and Fabrication: Translating generative models into a physical model made using the additive manufacturing technique.

In this way, undertaking module 4: Reflection and Evaluation - Documentation, critique, and iterative improvement of design outcomes can be viewed as a very pragmatic approach to assessing the project's status with the goal of potential planning enhancements.

Formative assessment and reflective journals were used to bring constant feedback and adaptive instruction at the end of each module.

Phase 3] Teaching–Learning Strategies

A pedagogical model in a studio was adapted, which promotes learning in a team and peer guidance. Design challenges, sketching workshops in a more algorithmic fashion, and guided workshops in problem-solving were used as instructional activities. Faculty acted more as guiding and not teaching mechanisms where the learners were allowed to be autonomous and explore as much as possible in terms of design. The methods of flipped classroom were employed whereby theoretical ideas were presented in the form of pre-class work, and the class hours were spent on active activities and dialogues.

Phase 4] Assessment and Feedback Mechanisms

It was process-oriented and product-oriented assessment, which was oriented on creativity, innovation, technical performance, and reflective depth. Rubrics that were applied to evaluate students accounted conceptual originality, algorithmic diversity and material sensitivity. Evaluations by peers and the faculty were integrated as part and parcel and encouraged critical discourse and group development. The feedback loop was necessary to strengthen learning by applying the cycles of prototyping and reflections.

Phase 5] Implementation Outcomes

When the implementation was done, students were found to be more engaged, confident in designing, and more flexible in problem-solving. Students who used to confront design processes in a sequential manner started working in non-sequential, generative processes, which showed greater susceptibility to vagueness and experimentation. The course led to interdisciplinary connections between engineering, art, and architecture, which confirmed the applicability of the curriculum to the wider STEAM education.

5. Implementation Case Study

A pilot implementation of the proposed framework of the curriculum was done in one of the courses, undergraduate design and fabrication course, in a multidisciplinary institution to validate the curriculum framework. The objective of the study was to determine the effect of generative design and 3D printing as part of an experiential learning structure on student engagement, creativity, and reflective practice. The learning space was set up as a digital learning studio, furnished with CAD workstations, 3D printers, and cloud-based generative design services. Thirty students took part, where engineering, architecture, and fine arts backgrounds were represented, which guaranteed a wide range of viewpoints and the level of skills. The implementation took ten weeks, which were the elements of the modular framework mentioned above. The course started with the workshops on principles of computational design and parametric modeling, including the Autodesk Fusion 360, Rhino 3D, and Grasshopper.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Overview of Student Projects

and Generative Design Parameters |

|||||

|

Project ID |

Design Theme |

Generative Tool Used |

Key Parameters / Constraints |

3D Printing Material |

Outcome Summary |

|

P-01 |

Ergonomic Desk Lamp |

Fusion 360 Generative Design |

Weight ≤ 300 g; Light reach 30

cm; Angle range 90° |

PLA |

Produced an optimized curved structure

reducing material usage by 22%. |

|

P-02 |

Modular Chair Joint |

Rhino + Grasshopper |

Load capacity > 150 kg; Joint angle

45–90° |

PETG |

Achieved lightweight joint geometry

with parametric fit for mass customization. |

|

P-03 |

Bio-Inspired Wall Panel |

Fusion 360 + AI Topology Tool |

Maximize airflow; Minimize mass by 40% |

ABS |

Generated organic cell structures with

enhanced aesthetic appeal and stiffness. |

|

P-04 |

Prosthetic Hand Grip |

Rhino + Grasshopper + Kangaroo Physics |

Grip force > 25 N; Weight < 150 g |

TPU |

Delivered flexible grip design

improving comfort and load distribution. |

|

P-05 |

Sustainable Architectural Bracket |

Fusion 360 Generative Design |

Stress < 25 MPa; Displacement < 2

mm |

PLA Recycled |

Demonstrated 40% reduction in material

waste with similar structural integrity. |

The variety of the student projects in this table illustrates that generative tools enabled exploring parameter space and suet Students were tasked to state design problems connected with ergonomics, sustainability, or structural optimization. They also engaged in experimentation with design options using generative algorithms and varying constraints, performance objectives and geometry. The weekly critiques also offered an iterative round of feedback on both faculty and peer levels, which led to an environment of collaborative ecosystem, in which ideas developed naturally out of computational experimentation. The generative design projects were rooted in actual world situations such as development of lightweight architectural joints, ergonomic furniture parts, and bio-inspired structural designs. Students were taken through the entire design-to-fabrication cycle, including algorithmic ideation and 3D printing and testing. Combination of digital simulation and physical prototyping enabled the learners to visualize and experiment on functional relationship of design variables and behavior of the materials. The practices grew adaptive mindsets, and students were able to detect and rectify the inefficiencies of the design by iterating based on data instead of trial of errors.

5.1. Observations and Learning Outcomes

Through the observations in the classroom setting, a marked change in the attitude of the students was observed, i.e. the attitude of technology as a passive tool was replaced by the attitude that technology is a co-creative partner in the design process. The learners showed better skills in decomposing problems, better spatial reasoning and more ability to think in a divergent manner. In reflective journals, there was a greater involvement of the mind because students explained how the creativeness of their thinking was influenced by generative systems. In quantitative terms post course surveys suggested that there were measurable improvements in the following areas of computing literacy, creativity confidence and conceptual abstraction.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Comparative Evaluation of Learning Outcomes Before and After

Implementation |

|||||

|

Learning Dimension |

Assessment Instrument |

Pre-Course Mean (SD) |

Post-Course Mean (SD) |

% Improvement |

Interpretation |

|

Computational Literacy |

Algorithmic Thinking Quiz (0–100) |

58.4 (±8.2) |

84.6 (±6.9) |

+44.8 % |

Significant gain in understanding

parametric and algorithmic logic. |

|

Design Creativity |

Creativity Index Rubric (1–5) |

2.9 (±0.5) |

4.3 (±0.4) |

+48.3 % |

Higher ability to generate divergent

design alternatives. |

|

Reflective Learning |

Journal Reflection Score (0–10) |

5.2 (±1.1) |

8.6 (±0.8) |

+65.4 % |

Improved depth of reflection and

self-assessment. |

|

Collaboration & Communication |

Peer Assessment (1–5) |

3.1 (±0.6) |

4.5 (±0.3) |

+45.2 % |

Enhanced team coordination and

cross-disciplinary dialogue. |

|

Problem-Solving Adaptability |

Design Iteration Count (per project) |

3.4 (±1.2) |

6.8 (±1.0) |

+100 % |

Increased willingness to iterate and

refine through data-driven feedback. |

The quantitative comparison indicates significant improvement in all the learning dimensions, which proves the idea that the generative-design + 3D printing strategy develops the ability to compose computational competence, confidence in creative skill, as well as reflective capacity. The application confirmed that generative design and 3D printing come together to facilitate whole-brain learning the integration of theory, computational and materialization of design. Generative systems were open ended, which fostered intrinsic motivation and continued interest and the end product of 3D printing supported conceptual learning. The faculty reflections made a special emphasis on the role of scaffolding of technical teaching with reflective dialogues, so that technological searching did not become detached of pedagogical purpose. This case study, therefore, offers a model that can be replicated to incorporate computational creativity in designing education.

6. Results and Analysis

Curriculum implementation outcomes and the related student projects showed that computational literacy, creativity, reflective learning, and problem-solving adaptability showed a noteworthy improvement. Both qualitative and quantitative studies proved that the combination of generative design and 3D printing resulted in tangible educational outcomes and changed the learning experience of enabling passive knowledge intake to active, discovery-based learning. Standardized assessment tools based on Bloom cognitive taxonomy and Kolb experiential learning model were used to undertake pre- and post-course assessments. As shown in Table 2, the average score of computational literacy went up by 44.8 to 84.6 (a 44.8-percent improvement), which means that the students became more competent in algorithmic thinking and digital modeling. The level of creativity increased by 48.3 percent, which testified to the effect of generative systems on broadening the ideation and divergent thinking. Reflective learning was refined by 65.4% which demonstrated the development of self-assessment and meta-cognitive awareness by systematic documentation and criticism. On the same note, peer collaboration and adaptability increased by more than 45 percent and this confirms the pedagogical effectiveness of cooperative generative design environments. The latter findings are indicative of the fact that parameter-driven design exploration does not only foster technical fluency, but it also increases the levels of higher-order thinking.

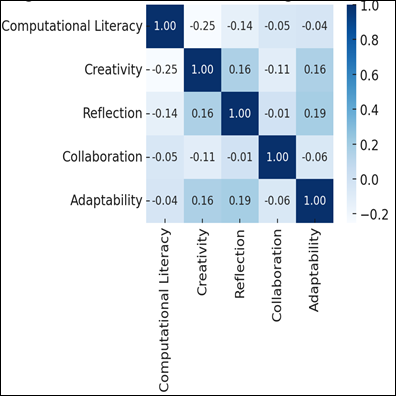

Figure 4

Figure 4 Correlation Matrix Among Learning Dimensions

The high-level of design iterations of 6.8 projects on average as compared to 3.4 were enough to show that students embraced iterative circles of problems and that shows resilience in design and reflective practice as shown in Figure 4. These findings were further supported by quality evidence captured using reflective journals, faculty observations, and interviews. Students indicated that they have a new appreciation of computational creativity, where they defined generative design as a co-creator that enabled them to find an idea rather than dictate it. It was found that reflective journals information indicated that learners found physical feedback of 3D-printed prototypes to be a crucial transition between abstract algorithms and material performance in the real world. Faculty reports highlighted the fact that this amalgamation of workflow promoted self motivation, self directed investigation and never ending experimentation- aspects that are typically hard to foster in conventional design pedagogy.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Distribution of Creativity and Reflection Scores

A comparative study of the generative design cohort and the past traditional 3D modeling cohorts showed that there was an existent big difference in pedagogy. Where the previous cohorts were concentrated on form replication and control over aesthetics, the generative cohort was concentrated on constraint based optimization and exploration by emergent generation, making the artifacts of that era more diverse and structurally efficient. The hybrid learning model was effective in achieving the culture of computational curiosity, which decreased the reliance on instructor guidance and enhanced creative autonomy. The iterative prototyping and collaborative reflection allowed changing the design process into an ecosystem of continuous feedback and support the constructivist concept of learning-by-making. To further demonstrate the level of improvement in all the learning dimension a radar chart Figure 5 is used to compare the pre- and post-intervention means score. The visualization is a clear indication of multidimensional developments in areas of computational, creative, and reflective factor, which proves the success of the curriculum in aligning theory, technology, and the learning aspect.

7. Future Directions and Recommendations

Generative design as a part of 3D printing education is a fundamental move towards redefining design education in the post-digital learning environment. Going forward, schools have to enhance this convergence in terms of curriculum development, inclusion of technology, and cross-disciplinary integration. The generative design needs to be integrated into future curricular models as an essential element of digital literacy and innovation education and not as a special elective within STEAM disciplines. Pre-inculcation of algorithmic thinking, simulation-based design and sustainability analysis at very initial stages of the curriculum may develop the capacity of students to integrate creativity with data-driven reasoning.

At the policy level, institutions and education boards ought to institute ethical and governance frameworks of the algorithmic authorship and intellectual property control and equal access to fabrication resources. The need to ensure relevance in the curriculum in the fast changing digital fabrication environments will be highly dependent on collaborative partnerships between academia, industry, and technology developers. Lastly, the study ought to be conducted longitudinally in future studies on evaluating the effectiveness of generative design learning on the long-term creativity, employability, and adaptability in solving problems. Through this progression in ensuring that inclusive and reflective pedagogical frameworks, teachers would be able to make sure that generative design remains not only a technological breakthrough but a learning philosophy that can transform the world to empower the student to build sustainable, intelligent and human-centered design futures.

8. Conclusion

The paper has demonstrated that generative design and 3D printing in educational setting can significantly transform the learning, innovating and creating process among students. The curriculum would interrelate the theoretical and the practice through the inclusion of the computational design processes into the learning experiences, which would constitute the technical competency and creative independence. The results revealed notable improvements in most learning domains, the most notable ones being the computational literacy, reflective practice, and design adaptability, which implies the pedagogic effectiveness of the combination of an algorithmic exploration and physical prototyping. Open-ended design tools have invited students to conceptualize design problems as an active system of exploration rather than a problem to be solved, and this stimulates a mind-set that is compatible with the constructivist and experiential learning theories. The reflective and collaborative features also improved cognitive involvement in the curriculum as the learner was able to internalize design rationale and thinking through practical experimentation. Nevertheless, the research also shed light into the fact that the ethical frameworks and pedagogical supports need to be present to overcome such problems as digital accessibility, the authorship of algorithms, and cognitive overload in the process of adaptation to a tool. These are some of the problems that should be addressed so as to have a sustainable and fair practice of generative design education. The conclusions made are that the generative design is not only an act of technological innovation but an act of paradigm shift in education, a paradigm that is balanced between creativity, computing and critical thinking. Making allows teachers to reinvent the thinking process of students so that they can produce a new generation of designers that is adaptive, reflective, and prepared to meet the demands of an AI-based creative world.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Aljabali, B. A., Shelton, J., and Desai, S. (2024). Genetic Algorithm-Based Data-Driven Process Selection System for Additive Manufacturing in Industry 4.0. Materials, 17, 4544. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17184544

Aman, B. (2020). Generative Design for Performance Enhancement, Weight Reduction, and its industrial Implications [arXiv preprint]. arXiv.

Chang,

C., Yang, Y., Pei, L., Han, Z., Xiao, X., and Ji, Y. (2022). Heat

Transfer Performance of 3D-printed Aluminium Flat-Plate Oscillating Heat Pipes

for the Thermal Management of LEDs. Micromachines, 13, 1949.

https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13111949

Chen, M. C., Zhao, Y., and Xie, Y. M. (2019). Topology Optimization and Additive Manufacturing of Nodes in Spatial Structures. China Civil Engineering Journal, 52, 1–10.

Khan, S., and Awan, M. J. (2018). A Generative

Design Technique for Exploring Shape Variations. Advanced Engineering

Informatics, 38, 712–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2018.09.005

Lu, S., Ma, D., and Mi, X. (2024). A

High-Throughput Circular Tumor Cell Sorting Chip with Trapezoidal Cross

Section. Sensors, 24, 3552. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113552

Mirzaei,

H., Ramezankhani, M., Earl, E., Tasnim, N., Milani, A. S., and Hoorfar, M.

(2022). Investigation of a Sparse Autoencoder-Based Feature Transfer

Learning Framework for Hydrogen Monitoring Using Microfluidic Olfaction

Detectors. Sensors, 22, 7696. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22207696

Muthumanickam, N. K., Duarte, J. P., Nazarian, S., Memari, A., and Bilén, S. G. (2021). Combining AI and BIM in the Design and Construction of a Mars Habitat. In The Routledge Companion to Artificial Intelligence in Architecture (pp. 251–279). Routledge.

Plocher, J., and Panesar, A. (2019). Review on

Design and Structural Optimisation in Additive Manufacturing: Towards

next-Generation Lightweight Structures. Materials and Design, 183, 108164.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2019.108164

Snijder, A. H., Linden, L., Goulas, C., Louter, C., and Nijsse, R. (2020). The Glass Swing: A Vector Active Structure Made of Glass Struts and 3D-Printed Steel Nodes. Glass Structures and Engineering, 5, 99–116. Https://Doi.Org/10.1007/S40940-020-00119-8

Vergara Vidal, J. E., Álvarez Campos, D., Dintrans Bauer, D., and Asenjo Muñoz, D. (2021). CORVI, Tipologías De Viviendas Racionalizadas: un ejercicio de estandarizacion. Arquitecturas del sur, 39, 118–137.

Wang, L. X., Du, W. F., Zhang, F., Zhang, H., Gao, B. Q., and Dong, S. L. (2021). Research on Topology Optimization Design and 3D Printing Manufacturing of Cast Steel Joints with Branches. Journal of Building Structures, 42, 37–49. (In Chinese).

Yu, W., Sing, S. L., Chua, C. K., and Tian, X. (2019). Influence of

Re-Melting on Surface Roughness and Porosity of AlSi10Mg Parts Fabricated by Selective

Laser Melting. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 792, 574–581.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.04.072

Zhao, Y., Chen, M. C., and Wang, Z. (2019). Additive Manufacturing Oriented Topology Optimization of Nodes in Cable-Strut Structures. Journal of Building Structures, 40, 58–68.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.