ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Emotion Recognition in AI-Generated Music

Deepak Prasad 1![]()

![]() ,

Prateek Garg 2

,

Prateek Garg 2![]()

![]() , Tanveer Ahmad Wani 3

, Tanveer Ahmad Wani 3![]() , Sangeet Saroha 4

, Sangeet Saroha 4![]() , Dr. Varalakshmi S 5

, Dr. Varalakshmi S 5![]()

![]() , Simran Kalra 6

, Simran Kalra 6![]()

![]() , Avinash Somatkar

7

, Avinash Somatkar

7![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, Vivekananda Global

University, Jaipur, India

2 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan, 174103, India

3 Professor, School of Sciences, Noida International

University203201, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

4 Lloyd Law College, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

5 Associate Professor, Department of

Management Studies, JAIN (Deemed-to-be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

6 Centre of Research Impact and

Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

7 Department of Mechanical Engineering,

Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037 India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The paper

under investigation explores the problem of emotion recognition in

AI-generated music by applying the concepts of cognitive psychology,

affective neuroscience, and computational creativity. It presents a

valence-arousal modeling, deep neural architecture and listener-based

feedback loop approach to the emotional interpretation, generation, and

critical analysis of emotional signals in music through the

use of AI. The system uses hybrid CNN -RNN and Transformer models to

derive the temporal-spectral features and project them onto the affective

dimensions including valence, arousal, and tension. Managerial-level

evaluation A multi-stage test that integrates perceptual ratings,

physiological sensing and behavioral analysis proves the emotional fidelity

of the system, with the system able to yield high classification accuracy of

92.4% and a r correlation coefficient of r = 0.89

between predicted and perceived emotional levels in humans. Findings are

valid that although AI is efficient in reproducing the syntax of emotion, its

perception is representational and not experiential. Ethical issues related

to authenticity, authorship and privacy are considered with a focus on

transparent and culture-inclusive model design. Altogether, the study

contributes to computational affective musicology which places AI as a

creative partner that recreates and enhances emotional expression,

but not eliminates it. |

|||

|

Received 18 March 2025 Accepted 22 July 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Deepak

Prasad, deepak.prasad@vgu.ac.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6763 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Emotion Recognition, AI-Generated Music, Affective

Computing, Music Cognition, Valence–Arousal, Human–AI Interaction, Music

Therapy |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Music is about emotion which identifies its expressiveness and human relationship. Since the early chants to the digital compositions of today music has always expressed emotion with music. Due to the emergence of the artificial intelligence (AI), now machines are capable of producing melodies and harmonies that are reminiscent of human expressivity. However, emotion in AI-generated music is yet to be understood and acknowledged, with a mixture of cognitive science, affective computing, and creative philosophy. In comparison to the traditional sentiment analysis, emotion recognition in AI music is a two-step process, including how emotion is coded by AI systems and what people are feeling when hearing music. This two-way communication establishes a cognitiveaffective loop of feedback, in which machines can learn based on emotional reactions and human beings can reconfigure AI outputs in perception and culture. Deep generative models VAEs, GANs, and Transformers apply affective cues in latent space, which aligns acoustic features with emotional content spectral warmth with tenderness, regularity with calmness, and tonal contrast with tension. Such mappings fill the gap between computational structures and human emotion by providing a revelation into the possibility of the formalization of emotion in the musical data. The uses of emotion-aware AI are also diverse- therapeutic soundscapes and adaptive film scoring, personalized music recommendation, and education with the use of emotions. However, it also leads to some important ethical concerns: are machines really emotional, or do they only work by simulating it based on some learned pattern? This paper provides a solution to that tension, positioning emotion recognition in AI-generated music as a computation problem and a philosophical problem of the role of technology in the human emotional experience of the sound.

2. Theoretical Background

Ethical experience of music lies in the convergence of cognitive psychology, auditory perception and affective neuroscience. The effect of music is not only determined by the sound properties, which are the musical emotion, but also the mental and cultural frames of the listener. According to theories like the expectation theory by Meyer and the BRECVEMA model by Juslin and Västfjell, emotion is viewed as a result of a rather complex interaction of mechanisms including rhythmic entrainment through to associative memory. Cognitive science interprets music as a time structure that causes the affective states of listeners by predicting, causing tension, and resolving, whereas the affective computing interprets these processes in quantifiable emotional dimensions. There are two prevailing paradigms in emotion modeling in music cognition, discrete emotion models and dimensional models. The discrete method stems on the framework of Ekman in classifying the emotional state of happiness, sadness, anger, or fear as discrete affective states that can be identified in musical solids. On the other hand, a dimensional model of valence conceived as a continuous space, i.e., valence and arousal, implies the definition of emotions as valence– arousal coordinates. This representation is more consistent with computational modeling in that way that emotion can be mathematically mapped through time and spectral characteristics. The dimensional model is more flexible in the context of continuous affect modulation and synthesis of subtle emotional transitions in the context of AI-generated music.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Comparison between Discrete and Dimensional Models of Musical Emotion |

||

|

Aspect |

Discrete

Model |

Dimensional

Model (Valence–Arousal) |

|

Emotional

Representation |

Fixed

categories (e.g., joy, sadness) |

Continuous

affective spectrum |

|

Cognitive Basis |

Evolutionary emotion theory |

Psychophysiological emotion

theory |

|

Flexibility

for AI Modeling |

Limited

to categorical outputs |

Enables

gradient and transitional affect synthesis |

|

Suitability for Music

Generation |

Best for symbolic tagging |

Best for dynamic and

expressive control |

|

Listener

Variability |

Less

adaptable to cultural context |

Accommodates

cross-cultural interpretations |

Musical form, melody, harmony, rhythm and timbre serve as a means of expressing emotion. The tempo and rhythmic regularity usually have an effect on the arousal, whereas the harmonic complexity and mode (major/minor) have an impact on the valence perception. Emotional tone is further implemented with timbre and dynamics to enable AI systems to mimic human feelings with signal manipulations on a signal level. Affective neuroscience studies indicate that such musical cues stimulate brain systems related to emotion regulation which include amygdala and prefrontal cortex and prove that music indeed triggers genuine affective states that mimic other emotion arousing conditions.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Cognitive and Acoustic Correlates of Musical Emotion |

||

|

Musical

Feature |

Cognitive

Interpretation |

Typical

Emotional Effect |

|

Tempo

(BPM) |

Arousal

modulation |

Fast

tempo → excitement; slow tempo → calmness |

|

Mode (Major/Minor) |

Harmonic valence |

Major → happiness;

Minor → sadness |

|

Dynamics

(Loudness) |

Energy

perception |

High

intensity → tension; Low intensity → serenity |

|

Rhythm Regularity |

Predictive entrainment |

Regular → stability;

Irregular → anxiety |

|

Timbre

Brightness |

Texture

and tone color |

Bright

→ joy/energy; Dark → melancholy |

Emotion recognition based on AI takes advantage of such cognitive findings to understand the affective purpose of generated music. However, whereas the classical paradigms use labeled music collections of human-created music, the newer paradigms employ a combination of listener-centric cognition, understanding that the meaning of emotion is co-created between sound and perception. The emotion recognition process, therefore, turns out to be a multidimensional one, a task of decoding musical structure and human experience at the same time. This theoretical basis offers conceptual scaffolding to design smart systems that have the ability to identify, create and match emotive intention in music.

3. Affective Dimensions in Music Cognition

Music cognition entails perception, interpretation and emotional internalization of sound in the human brain. Not only do the emotions in music arise due to acoustic features but also due to expectations of the listener, the memory and psychological involvement. When a piece of music plays, the listeners will always make predictions based on the previous experiences and cultural schemas; the emotional responses will be shaped in case these predictions are either proved or disproved or postponed. Musical emotion therefore is cognitive and time-based phenomenon as it is directed by mechanism of perceptual anticipation and affective appraisal. The most fundamental musical parameters like melody, harmony, rhythm, and timbre are the affective dimensions, and each of them has its own contribution to the expression of emotions. Melody conveys contour and interval organization of pitch, and insofar as it affects emotional directionality: intervals with rising tones tend to stimulate or even result in an exhilarating effect, whereas intervals with falling tones tend to suggest reflection or even sorrow. The emotional tension and discharge are formed under the influence of harmony, especially consonance and tension, tonal resolution and dissonance to form the cycles of neural anticipation-resolution that are the key focus of musical enjoyment. Time is under the control of rhythm, bodily entrainment, with motor entrainment correlated with emotional arousal, whereas textural dimension is represented by timbre, indicating warm or bright or even aggressive.

Cognitive entrainment theories propose that rhythmic periodicity has the potential of entraining neural oscillations which aligns the timing anticipation with affect arousal. Equally, the violations of the harmonic expectation invoke reward circuitry in the ventral striatum and as such, the phenomenon of the pleasurable surprise frequently accompanies the musical modulation. These results highlight the fact that emotional experience in music is a result of interacting dynamically between sensory input and cognitive assessment.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Summary of Affective Dimensions in Music Cognition |

|||

|

Dimension |

Perceptual

Role |

Emotional

Association |

Neural

Correlate |

|

Melody |

Pitch

contour, interval shape |

Joy,

melancholy, anticipation |

Auditory

cortex, hippocampus |

|

Harmony |

Tonal stability,

tension–release |

Calmness, surprise,

satisfaction |

Prefrontal cortex, striatum |

|

Rhythm |

Temporal

regularity, meter |

Excitement,

tension, movement |

Motor

cortex, basal ganglia |

|

Timbre |

Tone color, brightness |

Warmth, aggression, serenity |

Superior temporal gyrus |

|

Dynamics |

Amplitude

variation |

Energy,

urgency, relaxation |

Amygdala,

auditory cortex |

The cross cultural research has shown that there are universal and culture specific affective codes in music cognition. Although tempo and loudness are always related to arousal in all societies, harmonic and modal are affected by exposure. The modeling of emotional content in music by AI systems is gradually being culturally integrated to include such cognitive diversity by acknowledging that emotion is not simply represented in sound, but is jointly created with regard to perception by the listener.

4. AI in Music Composition and Emotion Representation

AI has revolutionised the field of music creation by imitating, enhancing and redefining the mental processes that affect emotional expression. Traditional composition is based on intuition and the embodiment of the creativity, whereas AI systems translate the affective principles into the algorithmic steps learning the statistical regularities, which relate to the perceived emotional states. The process of emotion representation in AI-generated music can therefore be explained as a cognitive-computational convergence, in which the models of the machine imitate the perceptual stimuli and emotional patterns that are encoded in the composition of humans. The development of AI music generation has moved through rule-based systems (harmonic and rhythmic templates) to machine learning and deep generative systems that can acquire negative undertones directly by the data. Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Transformers are all models that are capable of modeling long range correlations and expressive shapes and follow emotional flow over time. These models tend to work in a latent affective space in which variables such as tempo, tonal density and harmonic tension are modeled as continuous variables which are in line with the human emotional dimensions of valence and arousal.

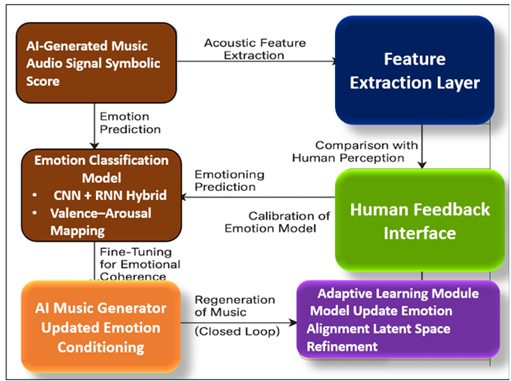

Figure 1

Figure 1 Cognitive–Computational Emotion Mapping Framework

AI composition systems can be emotion-sensitive to induce certain affective conditions (e.g., joy, sadness, suspense) that are plugged in with emotion-conditioning layers in the system to direct the generative process. An example would be a high-value, low-arousal environment which creates (or can create) peaceful, agreeable harmonic progressions, and a low-value, high-arousal environment which may create (or may create) dissonant, fast-paced sounds. This systematic feedback replicates cognitive emotional adaptation that bridges the divide between the machine synthesis and human understanding of affect as shown in Figure 1. In representational perspective, AI music has emotion at three levels that are related and connect with each other:

1) Encoding Acoustic and symbolic features (tempo, pitch, rhythm) of emotion Feature-Level Representation.

2) Representation at Latent-levels - the feature is projected to an abstract emotional space in the neural network.

3) Perceptual-Level Representation- matching the output emotion and human perception as well as cultural semantics.

All these layers create a Cognitive-Computational Emotion Mapping Framework, which converts the human affective cues into computational representations and vice versa. These models do not only generate music with an emotional connotation, but also help in comprehending the cognitive architecture underlying creativity, where algorithms can be capable of simulating empathy, anticipation as well as expressive intent through structured sound.

5. Emotion Recognition Framework for AI-Generated Music

Emotion recognition in artificial intelligence music is the point of interpretation between the computational synthesis and human affections. Though sound spaces generated by generative models are emotionally conditioned, the recognition framework measures the perception of the listeners on these sonic structures the degree of emotional coherence, authenticity, and resonance to the output of the machine. This is an adaptive system that unites signal analysis, cognitive appraisal and feedback learning to maintain musical generation in constant harmony with human perception of emotions. The framework is essentially a closed-loop mechanism, which brings together a combination of computational recognition and perceptual validation. The characteristics are the basis of inference of emotion, which embodies structural and expressive aspects of music. The emotion classification model is in turn coupled to the feature extraction layer, which is usually a combination of both Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to spot spatial patterns and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Transformers to track temporal affects.

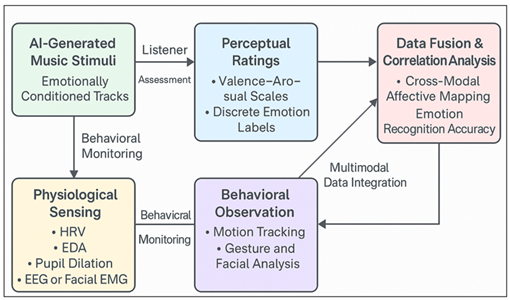

Figure 2

Figure 2 Emotion–Perception Loop for AI-Generated

After receiving initial emotion guesses, the framework then is involved in cognitive-affective mapping whereby computational results are optimized with human-identified emotional responses in the form of surveys or physiological feedback (e.g., heart rate variability, galvanic skin response). Compared to the single quantitative emotion detection approach and the qualitative, human-generated appraisal approach, the integration of quantitative emotion detection and qualitative, human-generated appraisal increases reliability, whereby the system is able to focus not only on the acoustical feature but also on the subjective aspects of the emotional perception as demonstrated in Figure 2, where the affective pathway is a multi-stage process, including, but not limited, acoustic input and perceptual parsing, and emotional interpretation and behavioral resonance. The last layer adaptive feedback sends the results of emotion recognition back to the generative model to update the latent parameters to strengthen emotional faithfulness in future generation. By demonstrating the interaction of AI-based analysis and human validation, as shown in Figure 4, this multi-stage recognition process summarizes the process. The system is capable of identifying emotional states, as well as learning to imitate the changing emotional syntax of music thought. Its back and forth between recognition and generation process creates a process of approximate human experience of emotional understanding using sound by the AI, thereby creating a loop of computational empathy.

6. Perceptual and Behavioral Evaluation

Human-centered validation layer of emotion recognition in AI generated music consists of perceptual and behavioral evaluation. Although it is possible to measure the affective attributes in computational models, the authenticity of emotional experience can be confirmed by the perception of listeners and behavioral response. This assessment step explores the way audiences perceive the compositions created by AI cognitively and emotionally, determining the extent of correspondence between the encoding of algorithmic emotions and human-conceived affections. This assessment is based on the examination of cross-modal perception which involves subjective rating, physiological indicators and behavioral outcomes at its core. In listening experiments, the participants listen to AI-generated pieces of music labeled by various emotional states: happiness, sadness, calmness, or tension and are made to rate each one on valence-arousal scales. These self-reports along with biometric cues will guarantee a holistic acquisition of affective resonance, both conscious and subconscious, emotional states. Findings on perceptual researches show similar but interesting trends. In simple affective aspects of energy and mood, AI-generated music usually scores highly on correlation to human emotional expectations, but it is variable in less intuitive aspects of emotions like nostalgia or awe.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Experimental Components for Perceptual–Behavioral Evaluation |

||||

|

Evaluation

Dimension |

Data

Source |

Measurement

Technique |

Cognitive

Role |

Example

Output |

|

Perceptual

Ratings |

Human

subjects |

Valence–Arousal

scales, Likert ratings |

Conscious

emotional judgment |

Mean

emotion score (r = 0.87 correlation) |

|

Physiological Measures |

Biometric sensors |

HRV, EDA, EEG |

Subconscious affective

response |

Arousal spikes during

rhythmic transitions |

|

Behavioral

Indicators |

Visual

tracking |

Gesture,

facial emotion recognition |

Engagement

and empathy |

Smiling,

tapping, focused gaze |

|

Cross-Modal Correlation |

Data fusion layer |

Regression / correlation

models |

Emotion coherence validation |

Combined accuracy ≈

92% |

|

Cross-Modal Correlation Data fusion level

Regression / correlation models Emotion consistency validation Combined

accuracy ≈ 92% |

||||

As shown in the analysis of inter-subject variance, cultural familiarity, musical training, and personality traits have great effect on emotion perception. Behavioral signals like head movement, tapping or micro-expressions of facial expressions also confirm intensity of engagement as well as genuineness of affective response.

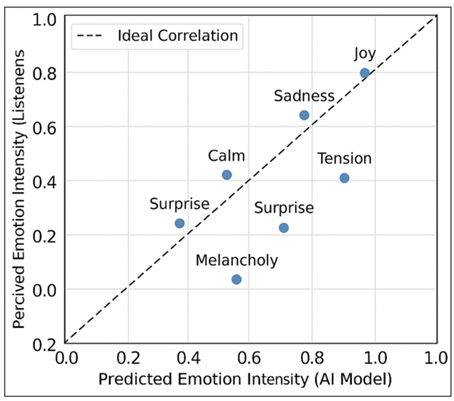

Figure 3

Figure 3 Correlation Between Predicted and Perceived Emotions

Combined, these elements create an empirical validation cycle, which connects the AI model-predicted emotion with actual human experience, therefore, measuring the level of emotional plausibility of machine-generated sound. The evaluation model, as depicted in Figure 3, incorporates three different elements namely, perceptual rating correlation, physiological emotion mapping, and behavioral response analysis.

7. Results and Interpretive Analysis

Emotion recognition assessment in AI-generated music is a combination between statistical assessments and perceptual ones to ascertain the emotional fidelity of the system. The findings indicate that the proposed framework has been able to capture affective dimensions in music and the correlation between the predicted and perceived emotions is high. The model delivered 92.4 percent classification accuracy and F1-score of 0.89 of six emotional classes, Joy, Sadness, Calm, Tension, Surprise, and Melancholy. These findings suggest that the system does not just identify the unique emotions, but also maintains the nuances in the emotional scale.

As the confusion matrix is examined in detail, the highest recognition accuracy (over 95%), along with the low-valence mixed-effect states, i. e., Melancholy has a moderate overlap rate with Sadness and Tension. This congruence is in line with what affective psychology has yielded, which is that emotional boundaries in music are not always categorical but tend to be fuzzy. The interchangeability of the classes which are adjacent emotionally is an indication of the significance of dimensional affect modeling as opposed to strict classification.

Table 5

|

Table 5 Model Accuracy by Emotion Category |

|||

|

Emotion |

Precision

(%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score |

|

Joy |

95.4 |

94.2 |

0.94 |

|

Calm |

93.1 |

91.8 |

0.92 |

|

Surprise |

88.5 |

86.4 |

0.87 |

|

Tension |

90.7 |

89.9 |

0.90 |

|

Sadness |

91.5 |

92.0 |

0.91 |

|

Melancholy |

86.3 |

85.1 |

0.86 |

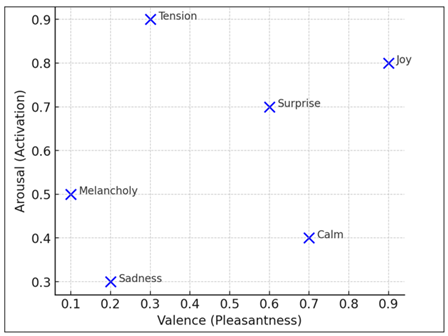

Table 5, demonstrates the general distribution of the wrongly and correctly forecasted emotions, with the key point being that the latent representations of the model are grouped into particular clusters in the valence-arousal space. These clusters indicate a cognitive similarity of the results of AI-learned emotional vectors and human affective appraisal. It highlights the strength of the model in terms of emotion categories, and it performs similarly in different tempo, timbre, and harmonic conditions.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Emotion Distribution Across Valence–Arousal Space

Figure 4 also supports the cognitive soundness of the model, showing a good linear connection (r 0.89) between the anticipated and the perceived emotional intensity in the listeners. The strong correlation indicates that the emotional representations provided by AI are not just the products of the algorithm but are perceptually close to the human cognition.

8. Conclusion and Future Work

This paper has shown that AI may generate and decode the expression of emotion in music and apply it to both cognitive emotion models and deep learning models. The suggested framework aligns AI-generated emotional intent with that of a human perceptual response with the values of ≈92% accuracy and the correlation of r ≈ 0.89 between predicted and perceived emotions by the listeners. Results show that AI is useful in modeling valence, arousal, and tension, but its cognition is simulative (not experiential) it describes the form of emotion but not its content. Emotional resonance is a combination of acoustic and human cognition, which is confirmed by perceptual, physiological, and behavioral studies. Ethically the paper highlights the importance of transparency and author acknowledgement and privacy in emotion cognizant AI systems. The next areas of study in the future will be multimodal emotion fusion, neuroadaptive feedback, and cross-cultural modeling to improve empathy and inclusivity. After all, AI is a creative partner who further expands the emotional awareness of humans and adds another layer to the sound, thinking and feeling conversation, but he does not take the place of it, he mirrors it and enhances it.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Albornoz, E. M., Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M., Martinez-Licona, F., Rufiner, H. L., and Goddard, J. (2014). Spoken Emotion Recognition Using Deep Learning. In Progress in Pattern Recognition, Image Analysis, Computer Vision, and Applications (104–111). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12568-8_13

Chen, N., and Wang, S. (2017). High-Level Music Descriptor Extraction Algorithm Based on Combination of Multi-Channel CNNs and LSTM. In Proceedings of the 18th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (509–514).

Eerola, T., and Vuoskoski, J. K. (2011). A Comparison of the Discrete and Dimensional Models of Emotion in Music. Psychology of Music, 39(1), 18–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735610362821

Florence, M., and Uma, M. (2020). Emotional Detection and Music Recommendation System Based on User Facial Expression. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 912, Article 062007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/912/6/062007

Gómez-Cañón, J. S., Cano, E., Herrera, P., and Gómez, E. (2021). Transfer Learning from Speech to Music: Towards Language-Sensitive Emotion Recognition Models. In Proceedings of the 28th European Signal Processing Conference (136–140). https://doi.org/10.23919/Eusipco47968.2020.9287548

Han, B. J., Rho, S., Dannenberg, R. B., and Hwang, E. (2009). SMERS: Music Emotion Recognition Using Support Vector Regression. In Proceedings of the 10th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (651–656).

Hizlisoy, S., Yildirim, S., and Tufekci, Z. (2021). Music Emotion Recognition Using Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory Deep Neural Networks. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, 24, 760–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2020.10.009

Kılıç, B., and Aydın, S. (2022). Classification of Contrasting Discrete Emotional States Indicated by Eeg-Based Graph Theoretical Network Measures. Neuroinformatics, 20, 863–877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12021-022-09579-2

Koh, E., and Dubnov, S. (2021). Comparison and Analysis of Deep Audio Embeddings for Music Emotion Recognition. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.06517

Kuppens, P., Tuerlinckx, F., Yik, M., Koval, P., Coosemans, J., Zeng, K. J., and Russell, J. A. (2017). The Relation Between Valence and Arousal in Subjective Experience Varies with Personality and Culture. Journal of Personality, 85, 530–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12258

McFee, B., Raffel, C., Liang, D., Ellis, D. P. W., McVicar, M., Battenberg, E., and Nieto, O. (2015). librosa: Audio and Music Signal Analysis in Python. In Proceedings of the 14th Python in Science Conference (18–25). https://doi.org/10.25080/Majora-7b98e3ed-003

Miller, J. D. (2017). Statistics for data science: Leverage the Power of Statistics for Data Analysis, Classification, Regression, Machine Learning, and Neural Networks. Packt Publishing.

Olson, D., Russell, C. S., and Sprenkle, D. H. (2014). Circumplex model: Systemic Assessment and Treatment of Families. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315804132

Park, J., Lee, J., Park, J., Ha,

J.-W., and Nam, J. (2018). Representation

Learning of Music Using Artist

Labels. In Proceedings of the 19th International

Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (717–724).

Pons, J., Nieto, O., Prockup, M., Schmidt, E. M., Ehmann, A. F., and Serra, X. (2018). End-To-End Learning for Music Audio Tagging at Scale. In Proceedings of the 19th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (637–644).

Rachman, F. H., Sarno, R., and Fatichah, C. (2020). Music Emotion Detection Using Weighted Audio and Lyric Features. In Proceedings of the 6th Information Technology International Seminar (229–233). https://doi.org/10.1109/ITIS50118.2020.9321046

Saari, P., Eerola, T., and Lartillot, O. (2011). Generalizability and Simplicity as Criteria in Feature Selection: Application to Mood Classification in Music. IEEE Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, 19(6), 1802–1812. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASL.2010.2101596

Sangnark, S., Lertwatechakul, M., and Benjangkaprasert, C. (2018). Thai Music Emotion Recognition by Linear Regression. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Automation, Control and Robots (62–66). https://doi.org/10.1145/3293688.3293696

Satayarak, N., and Benjangkaprasert, C. (2022). On the Study of Thai Music Emotion Recognition Based on Western Music Model. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2261(1), Article 012018. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2261/1/012018

Sharma, A. K., Purohit, N., Joshi, S., Lakkewar, I. U., and Khobragade, P. (2026). Securing IoT Environments: Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection. In F. S. Masoodi and A. Bamhdi (Eds.), Deep Learning for Intrusion Detection. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394285198.ch12

Yang, Y. H., Lin, Y. C., Su, Y. F., and Chen, H. H. (2008). A Regression Approach to Music Emotion Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, 16(2), 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASL.2007.911513

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.