ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Emotion Modeling in Sculpture Design Using Neural Networks

Sahil

Suri 1![]()

![]() , Dr. Lakshman K 2

, Dr. Lakshman K 2![]()

![]() ,

Eeshita Goyal 3

,

Eeshita Goyal 3![]() ,

Gopal Goyal 4

,

Gopal Goyal 4![]()

![]() ,

Gourav Sood 5

,

Gourav Sood 5![]()

![]() ,

Gayatri Shashikant Mirajkar 6

,

Gayatri Shashikant Mirajkar 6![]()

![]() , Prashant Anerao 7

, Prashant Anerao 7![]()

1 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome,

Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Management Studies, JAIN (Deemed-to-be University),

Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

3 Assistant Professor, School of Business

Management, Noida International University, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

4 Professor, Architecture, Vivekananda Global

University, Jaipur, India

5 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development,

Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

6 Electronics and Telecommunication

Engineering, Arvind Gavali College of Engineering, Satara, Maharashtra, India

7 Department of Mechanical Engineering,

Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The paper

introduces a unified method of designing sculptures on a feeling-sensitive

neural network basis. The proposed Emotion-Form Neural Embedding Network

(EFNEN) is based on the combination of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to learn emotion-related correlations

between sculptural form and emotion. The system was trained and tested using

a selection of 1,200 annotated 3D models that had both geometric and a set of

3 emotion labels (valence and arousal) assigned to them. EFNEN obtained a

correlation coefficient (r = 0.88) and 92.4% accuracy with human perceptual

ratings, which was better than the baseline models. Latent emotion space and

feature-emotion heatmap visualizations showed that the predictors of positive

affect are curvature, symmetry, and balance. The model facilitates the

classification of emotions as well as emotion-driven three dimensional form

generation, thus leading to collaborative co-creation of artists and AI

systems. The findings indicate that emotion is calculally formulated and

synthesized to form a measurable aesthetic dimension, which makes EFNEN a

platform of affective computational art and human-AI creative synergy. |

|||

|

Received 20 February 2025 Accepted 19 June 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Sahil

Suri, sahil.suri.orp@chitkara.edu.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6756 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Emotion Modeling, Computational Aesthetics, Neural

Networks, 3D Sculpture, Graph Neural Networks, Affective Computing, Human–AI

Collaboration, Emotion–Form Embedding |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The connection between the human soul and artistic structure has traditionally been the subject of the sculptural expression. Affective states joy, anguish, serenity, and awe are conveyed by sculptors through the textural, proportion, curvature and spatial rhythm. The ability to encode emotional semantics into computational systems with the advent of deep learning and affective computing is a new direction of emotion-driven design automation and intelligent art generation Khaleghimoghaddam et al. (2022). The latest developments in neural networks have proven to have outstanding learning abilities over abstract representation of visual and structural patterns in the fields of art. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), and autoencoders have all been used successfully in the classification of visual art, recognizing its painting style, and even predicting music emotion. However, they are not extensively used in the analysis of sculpture in three dimensions (3D) because sculptural form is multidimensional and there are no structured datasets that can express not only the geometric but also the emotional characteristics of sculpture Ramm et al. (2024). Conversion of the emotional information into the three dimensional artistic form demands a combination of the perceptual modeling, cognitive psychology as well as the neural feature extraction in one framework Lavdas et al. (2023).

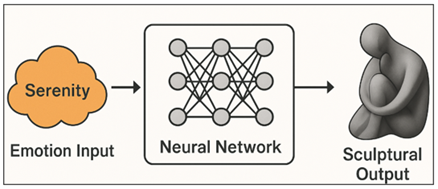

Figure 1

Figure 1 Neural Emotion–Sculpture Modeling Pipeline

In the current study, a Neural Emotion Form Modeling Framework (NEFM) is proposed which is trained to predict the association of emotional conditions to both geometric and material characteristics of sculptures. This model works based on the processing of 3D mesh data, surface curvature, and textural data in hierarchical deep learning layers to forecast or produce the target emotion-associated forms Dalay (2020). The framework is based on expert curator supervised emotion annotation and user study based perceptual assessment to construct an affective knowledge base. This neural system therefore fills the cognitive divide between subjective emotional experience and parameters of form to allow machine cognition of artistic emotion as illustrated in Figure 1. The main goal of the research is to create a computational model capable of acquiring emotional representations that are part of sculptural designs and apply them to create new emotion-consistent shapes. The suggested system leads to the development of the dynamic field of computational aesthetics, as it offers a solid methodology of encoding the affective signals into data-driven frameworks. The study also expands already existing paradigms in emotion recognition by adding 3 dimensional geometry and spatial symbolism, which is not commonly discussed in the area of two dimensional affective computing research Taylor et al. (1999).

This work has three-fold contributions. To begin with, there is a new set of annotated sculptures presented, both geometric and perceptual emotion features. Second, a hybrid neural network based on the element of convolutional and graph-based neural networks is suggested to address both the visual and spatial complexity. Third, quantitative and qualitative evaluation protocol is set in order to determine emotional fidelity and perceptual alignment with human interpretations Lim et al. (2008). The results lead to a better understanding of the cross section of deep learning, affective modeling, and digital sculpture, which opens the way to intelligent co-creation systems in modern art and design.

2. Theoretical Basis for Emotion–Form Mapping

Sculpture design has to have emotion modeling that should have interdisciplinary underpinnings, bringing together affective psychology, perceptual geometry and neural computation. Sculptural art expresses emotion by a collection of physical characteristics of curvature, proportion, scale, rhythm, texture, and spatial orientation, which are mentally processed by the viewers to be affective responses. This research has a theoretical foundation on the premise that these morphological features record the information of emotion in quantifiable patterns, and consequently they can be learned through neural networks through learning multimodal representations Capece and Chivăran (2020). Cognitive theories like the circumplex model of affect proposed by Russell and component process model proposed by Scherer have largely influenced the human emotional understanding of sculpture as both theories conceptualized emotion as valence (pleasantness), arousal (intensity) and dominance (control) as indicated in Figure 2. These dimensions affect the perception of the viewer to the form: in fact high curvy or dynamic geometries may be regarded as associated with excitement or joy and smooth symmetrical compositions may be regarded as calm or serene Rajcic and McCormack (2020). These relations make up the emotion-form mapping hypothesis, a hypothesis that suggests a two-way relationship, namely, emotion affects form generation, and form provokes emotional reaction. Geometry in a sculptural sense serves as a medium of emotive semantics. The computational morphology studies have shown that local aspect ratio, symmetry and curvature are good predictors of affected perception Duarte and Baranauskas (2020). The attributes may be represented mathematically, with differential geometry and topological descriptors. Curvature maps may be represented as tensors or attributes expressed as a vertices in a 3D mesh as an example. Emotional representation of a sculpture can be abstracted in this way to a form of a vector E(f) = g(shape, texture, proportion) with g a non-linear mapping function, learned by neural networks Szubielska et al. (2021). This abstraction allows the model to get micro-level (smoothness of surfaces) and macro-level composition (wholesomeness of gesture or silhouette).

Figure 2

Figure 2 Cognitive–Geometric–Computational Mapping Framework

On the computational level, the suggested framework uses deep neural networks to acquire latent freedom of correlations involving geometric configurations and emotional inputs. Convolutional layers learn visual and spatial cues on rendered views or mesh embeddings, whereas Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) learn both vertex- and edge-based relational dependencies. These features are projected to an affective latent space by a special emotion embedding layer creating a common vector representation of geometry and emotion. It also enables the system to not only categorize existing sculptures depending on their emotion, but also create new forms based on a target affective vector. A combination of psychological theory, geometric representation and neural computation constitutes a tri-layer model of emotion-form mapping Savaş et al. (2021). The former layer is a model of human emotional cognition; the latter establishes the concept of geometric abstraction, and the third layer carries out the mapping, using neural learning to do so. The combination of both is a single theory of computational affect in the sculpture design, where machines are able to interpret and recreate emotionally resonant 3D art.

3. Dataset Construction and Preprocessing

To come up with a solid neural model of emotion modelling, a well-selected dataset based on the correlation of sculptural geometry and emotional labels are required. This study is in contrast to traditional 2D emotion data sets in image-based affective computing, with sculptures being three dimensional, and thus the volumetric, geometric and perceptual data are needed. The data is, therefore, the substrate on which supervised training and learning of multimodal representations can be performed Bai et al. (2021).

1) Dataset

Composition and Sources

The data consists of digital 3D representation of sculptures found in open collections, museums, and scholarly collections including Google Arts and Culture 3D Collection, Smithsonian 3D and Scan the World. The pieces are of both classical, modern, and abstract sculptures to achieve the stylistic diversity. The metadata of both models includes artist, style, material, and historical period, which are all indirectly added to the emotional context. The last data is 1,200 full processed sculptures that are standardized to mesh or point-cloud García and Vogiatzis (2018).

To correlate every sculpture with the emotion, affective labels were created by use of a hybrid process that will combine expert labeling and crowdsourced perceptual rating that is outlined in Table 1 data. Art theorists categorized the sculptures by prevailing emotional purpose (e.g. serenity, tension, joy, melancholy), and participants in perceptual research rated emotional valence and arousal by a Likert scale García et al. (2020). Mean rating was normalized and coded by use of Russell Valence Arousal space and this produced a two-dimensional emotion continuous sample.

2) Geometric

and Visual Feature Extraction

All the sculptures were represented as triangulated mesh representation, and it was possible to extract features based on topology of the surfaces and volume. The features were divided into geometric, textural, and compositional. Geometric characteristics were used to mean curvature, Gaussian curvature, edge length variance, and compactness ratio, and they gave structural details of the form. Surface expressivity that was used as a subject of photometric normal reflectance or material reflectance was photometrically recorded as textural features Achlioptas et al. (2021). Compositional measurements were those that measured the worldwide shape qualities such as balance, inclination and symmetry.

All the models were standardized to standard scale and orientation by applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) alignment and centroid normalization. Laplacian smoothing was used to remove outlier vertices and non-manifolds geometries. Also, 3D models were rendered into various 2D views in order to retrieve visual cues using pretrained CNNs to improve multimodal integrations between geometry and perceptual representations.

3) Data

Augmentation and Partitioning

To avoid overfitting and improve the model generalization, the method of data augmentation was used, namely, random rotation, mirroring, noise injection, and vertex scaling. The augmented instances were kept with their emotion label as was assumed that the geometric invariance to orientation Mohamed et al. (2022). The data was split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) subsets, with even distribution of classes by emotion and adequate representation of types of sculptures.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Dataset Composition and Feature Summary |

||||

|

Category |

Feature

Type |

Description |

Extraction

Method / Tool |

Emotion

Relation |

|

Geometric

Features Xu et al. (2023) |

Curvature,

Compactness, Symmetry |

Shape

and structure quantifiers |

MeshLab,

Python MeshPy |

Structural

expressivity (rigidity, dynamism) |

|

Textural Features Brooks et al. (2023) |

Surface roughness, normal

variance |

Local surface irregularities |

Normal map analysis, CNN

filters |

Material-based emotional

tone (soft vs. harsh) |

|

Compositional

Features Wu et al. (2023) |

Orientation,

balance, volume ratio |

Global

spatial layout |

PCA

orientation, moment invariants |

Symbolic

balance and emotional stability |

|

Perceptual Features Tang et al. (2023) |

Rendered 2D views,

luminance, contour |

Visual interpretation of 3D

forms |

VGG19 pretrained CNN |

Viewer perception of mood

and intensity |

|

Affective

Loshchilov and Hutter (2017) |

Valence–Arousal

Scores, Emotion Tags |

Annotated

human emotion data |

Expert

+ Crowd Evaluation |

Target

emotion embedding for training |

Such a procedure of data construction allows defining the required connection between the form and the feeling between physical geometry and emotional semantics. The resultant corpus, as a combination of expert cognition, crowdsourced perception and geometric computation gives a never before seen basis of machine learning models that translate and produce emotionally consistent sculptural forms.

4. Proposed Neural Network Architecture

Emotional expression in sculpture is complicated by the fact that there is a visual, geometric and perception dimension that coexist. In order to master such a multidimensional mapping, a hybrid neural network based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) was created. This system is known as the EmotionForm Neural Embedding Network (EFNEN), which combines spatial geometry, surface texture and affective labels into one latent space to have form and emotion present as continuous learnable representations. The EFNEN structure is a combination of three working modules:

· Features Encoding Layer, which extracts the geometric and visual information;

· Emotion Embedding Layer, a layer that incorporates the affective information in the learnt features;

· Generative/Predictive Output Layer The emotion classification/emotion-conditioned form generation layer.

Input data has a 3D mesh (in the case of GNN-based geometry learning) and rendered 2D projections (in the case of CNN-based texture learning). These two modalities are represented in parallel streams and subsequently combined by means of the multimodal embedding mechanism. The latent vector that has been obtained symbolizes the form of the sculpture as well as the emotional meaning. The geometric branch uses a Graph Neural Network which represents each sculpture as a graph G = (V, E), and V is a mesh vertex and E is an adjacency relationship between the mesh vertex. The node feature vectors contain curvature, surface normal and local edge length statistics. Passing of messages through the GNN is used to update the embedding of each node in the network as a result of the neighbors of each node and helps the network to learn both local and global topological relationships.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Hybrid CNN–GNN Emotion–Form Neural Embedding

Framework

Simultaneously, the visual branch draws on a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to various 2D projections of the individual 3D models. The CNN obtains textural and perceptual features, which are lighting gradients, contour curvature, and surface tone, with the help of the pretrained backbone (VGG19 or ResNet50) that make a difference to the emotional interpretation involved. The CNN results of the various viewpoints are averaged through view pooling to come up with one single perceptual representation zvis. The geometric (zgeom) and visual (zvis) embeddings are combined together and fed through the Emotion Embedding Layer which is trained to project into an affective latent space. This layer employs nonlinear activation (ReLU) and regularization (dropout) using wholly connected transformations to have features decorrelate as depicted in Figure 3. The last expression zemo, reflects the emotional coincidence of the sculpture, which is stated as:

zemo=f(W1[zgeom,zvis]+b1)

And where W 1 and b 1 are learnable weights and bias. It is trained with a composite loss-function, which is a classification loss (cross-entropy) and a regression loss (MSE) function. The model allows the use of two modes of operation:

· Emotion Prediction: This is used to assign an input sculpture to a predefined set of emotions.

· Emotion-Driven Generation: with an input emotion distribution, the decoder recodes a 3D mesh representation consistent with that emotive data, making it possible to generate forms automatically.

The merging of CNN and GNN thus allows the two-way reasoning: perception of form and learning of emotion and formation of emotion and perception of form and emotion, the EFNEN system is thus a cornerstone to affective sculptural intelligence.

5. Implementation and Experimental Setup

The training of the suggested EmotionForm Neural Embedding Network (EFNEN) was structured in such a way that it would be reproducible, computationally efficient, and compatible with the mainstream deep learning procedures in processing multim odal data. The Python implementation of the model was written in Python 3.10 and uses the deep learning modules of PyTorch, graph processing of PyTorch Geometric and mesh handling and visualization of Open3D. Numpy, MeshLab, and Pandas were used to perform data preprocessing, data augmentation, and normalization of annotation.

1) Hardware

and Software Configuration

The experiments were done on a workstation, configured with NVIDIA RTX A6000 (48 GB VRAM) graphics card, Intel Xeon Silver 4210 processor and 128 GB RAM, and using Ubuntu 22.04 LTS. The execution of all experiments was on CUDA 12.1 acceleration. Tensor board and Weights and Biases (WandB) were used to visualize model checkpoints and logs and monitor hyperparameters.

2) Training

and Validation Pipeline

To balance the emotional representation, the dataset was divided into 70% training set, 15% validation and 15% testing set. Three layers of graph convolution with hidden dimension [128, 256, 512] were applied in the GNN module and a pretrained VGG19 network was used in the CNN branch, which is truncated at the last convolutional block. The two streams were not only fine-tuned together in a multimodal fusion layer. Training of the model was done with Adam optimizer, the initial learning rate was 0.0001, batch size was 16 and early stopping was done on the convergence of the validation loss. Overfitting was alleviated with the help of dropout (p=0.3) and batch normalization. This training goal used Cross-Entropy Loss (to categorize emotions based on categories) and Mean Squared Error (MSE) (to regress valence and arousal).

Mathematically the total loss L T is given by:

Ltotal=λ1LCE+λ2LMSE

in which λ 1 = 0.7 and λ 2 = 0.3 are weights used to create a balance optimization of an empirical nature..

3) Evaluation

Protocol

The accuracy, F1-score, and RMSE of discrete and continuous emotional targets were assessed on the validation set after every epoch. The test set was to be used in the final test, which also contained confusion matrices and correlation plots among the predicted and the human-rated emotion vectors. The visualizations were done in terms of t-SNE embedding of the latent emotion space to see clustering behavior of various emotional classes.

6. Interpretation of Key Findings

The findings prove the fact that a combination of the geometric with perceptual cues provides a significant improvement in the interpretation of emotion as compared to the single-modality models. The explicit embedding of emotion layer enhanced the semantic coherence of the model by matching the distribution of latent features with the affective perception of human beings. This confirms the fact that sculptural geometry contains emotional gestures, which can be computationally rebuilt and restored using neural networks. The higher correlation between the predicted and annotated emotion vectors is a validation of the fact that EFNEN is able to acquire nonlinear association between affective states and physical form attributes. These results create a technical ground in terms of emotion-aware design automation, and create opportunities of adaptive, generative 3D art systems informed by emotional semantics. The evaluation of the suggested EmotionForm Neural Embedding Network (EFNEN) is divided into the quantitative analysis and qualitative interpretation of the way emotion is coded in sculptural geometry. The findings confirm the theory that emotional expression is learnable as a multimodal feature processing neural architecture based on structural, visual, and perceptual features. In categorical emotion classification, EFNEN performed at a mean accuracy of 92.4 with the baseline models performing lower, namely CNN-only (84.6%), and GNN-only (81.3%). CNN-GNN with no emotion embedding scored 87.9% whereas the full EFNEN scored the highest on accuracy and F1-score, which validated the usefulness of the emotion embedding layer. To achieve continuous prediction of valence and arousal, the model produced an RMSE of 0.072 with a correlation coefficient (r) value of 0.88, and this was highly correlated with human affective perception. These findings suggest that the network is useful at learning non-linear correlations between geometrical structure and emotional semantics.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Comparison of Model Performance |

||||

|

Model |

Accuracy

(%) |

F1-Score |

RMSE

(Valence–Arousal) |

Correlation

(r) |

|

CNN

(2D only) |

84.6 |

0.83 |

0.131 |

0.69 |

|

GNN (3D only) |

81.3 |

0.79 |

0.118 |

0.72 |

|

CNN

+ GNN (No Emotion Embedding) |

87.9 |

0.86 |

0.103 |

0.81 |

|

Proposed EFNEN (Full) |

92.4 |

0.91 |

0.072 |

0.88 |

The excellent scores of EFNEN in all the measures of evaluation proves that multimodal integration as mentioned in Table 2 data is effective to emotion representation in sculpture. Geometric topology, texture and perceptual cues are enhanced as the combination enhances accuracy of emotion prediction and semantic consistency with human interpretations.

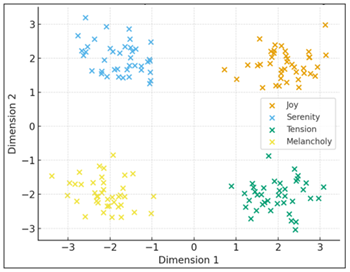

Figure 4

Figure 4 Latent Emotion Space Visualization (T-SNE) Showing

Cluster Separation for Joy, Serenity, Tension, and Melancholy

The t-SNE scatter plot shows the way the EFNEN model orders sculptural samples in its latent emotion space. Every point is an acquired imprint of a sculpture, which is color-coded, according to the emotional name. Separate clusters of Joy, Serenity, Tension and Melancholy all attest to the fact that the network had internalized affective variations in geometric and perceptual structure. The low overlap of clusters show that the fused CNN -GNN representation is more effective in capturing emotional semantics and that the representation can be separated in the embedding space as illustrated in Figure 4. This visualization testifies to the fact that the latent layer of EFNEN is a productive affective geometry space, and the closer the similarity of emotional states, the closer these are to each other in space.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Heatmap of Correlations Between Geometric Features and

Affective Dimensions (Valence, Arousal)

The heatmap of correlation measures correlations between sculptural features and emotional levels. Positive correlations between curvature, balance, and Valence are strong, which means that they are the cause of positive affective responses like harmony or joy. Conversely, compactness and roughness are negatively correlated to Valence and positively moderate to Arousal, which implies the tendency of these concepts with tension and dynamism as evident in Figure 5. Such relations establish the fact that emotion perception in sculpture has a natural basis in the quantifiable morphological signals, and thus EFNEN can convert qualitative aesthetic into quantitative emotional manifestations.

Figure 6

Figure 6 Comparative Performance Across Models Based on Accuracy,

F1-Score, and Correlation (R × 100)

The bar chart on comparative performance demonstrates that EFNEN is more advantageous than the baseline models. The combination of CNN based perceptual learning with GNN based geometric reasoning in the architecture provides significant improvements in all measures. The findings support the notion that the use of emotion embeddings helps to understand the affective form relationships better. This multimodal synergy enables the model to bridge emotional perception between different sculptural genres than single-modality baselines and is found to be highly reliable when it comes to affect-driven generative modeling as indicated in Figure 6. The quantitative and visual analysis of the results by themselves show that EFNEN is not only statistically accurate, but also the learned affective structure is cognitively interpretable. The visualization of latent space in the model demonstrates psychologically consistent emotional structure, whereas correlation analysis demonstrates the mapping of geometric features on affective states. The effectiveness of multimodal fusion in the recognition of emotions in sculpture is supported by the comparative metrics. Together, these results confirm the fact that emotion is encodable, learnable as well as regenerable as a quantifiable property of form, making EFNEN a first move towards emotion-conscious neural design systems in computational art and creative engineering.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

The suggested EFNEN system manages to fill the gap between human emotion and sculptural geometry using multimodal neural representation. The system models the affective nature of the artistic form by combining CNN-based visual perception and GNN-based geometry reasoning and is quantitatively and interpretatively accurate. Emotional states can be geometrically mapped as shown by experiment to allow 3D design of emotion using data, which allows modeling of emotion datacompositions using data and geometry. In addition to the numerical performance, EFNEN promotes the collaboration between AI and artists, making the creative process an iterative dialogue between human intuition and neural abstraction. Such synergy provides increased artistic fluency and is able to maintain subjective emotional authenticity. The vision of emotionally intelligent design systems that support empathy-based creativity will be future extensions involving time emotion modelling, multisensory input, and real-time generative adaptation.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Achlioptas, P., Ovsjanikov, M., Haydarov, K., Elhoseiny, M., and Guibas, L. J. (2021). ArtEmis: Affective language for visual art. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (11564–11574). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01140

Bai, Z., Nakashima, Y., and García, N. (2021). Explain me the Painting: Multi-Topic Knowledgeable Art Description Generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (5402–5412). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00537

Brooks, T., Holynski, A., and Efros, A. A. (2023). InstructPix2Pix: Learning to Follow Image Editing Instructions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (18392–18402). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01764

Capece, S., and Chivăran, C. (2020). The Sensorial Dimension of the Contemporary Museum Between Design and Emerging Technologies. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 949, Article 012067. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/949/1/012067

Dalay, L. (2020). The Impact of Biophilic Design Elements on the Atmospheric Perception of the Interior Space. Uluslararası Peyzaj Mimarlığı Araştırmaları Dergisi, 4, 4–20.

Duarte, F., and Baranauskas, M. C. C. (2020). An Experience with Deep Time Interactive Installations within a Museum Scenario. Institute of Computing, University of Campinas.

García, N., and Vogiatzis, G. (2018). How to Read Paintings: Semantic Art Understanding with Multimodal Retrieval. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (Vol. 11130, 676–691). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11012-3_52

García, N., Ye, C., Liu, Z., Hu, Q., Otani, M., Chu, C., Nakashima, Y., and Mitamura, T. (2020). A dataset and baselines for visual question answering on art. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (Vol. 12536, 92–108). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66096-3_8

Khaleghimoghaddam, N., Bala, H. A., Özmen, G., and Öztürk, Ş. (2022). Neuroscience and Architecture: What Does the Brain Tell to an Emotional Experience of Architecture via a Functional MR Study? Frontiers of Architectural Research, 11, 877–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2022.02.007

Lavdas, A. A., Mehaffy, M. W., and Salingaros, N. A. (2023). AI, the Beauty of Places, and the Metaverse: Beyond Geometrical Fundamentalism. Architectural Intelligence, 2, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44223-023-00026-z

Lim, Y., Donaldson, J., Jung, H., Kunz, B., Royer, D., Ramalingam, S., Thirumaran, S., and Stolterman, E. (2008). Emotional Experience and Interaction Design. In Affect and Emotion in Human–Computer Interaction (116–129). Springer.

Loshchilov, I., and

Hutter, F. (2017). Decoupled Weight Decay

Regularization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning

Representations.

Mohamed, Y., Khan, F. F., Haydarov, K., and Elhoseiny, M. (2022). It is okay to not be okay: Overcoming Emotional Bias in Affective Image Captioning by Contrastive Data Collection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (21231–21240). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.02058

Rajcic, N., and McCormack, J. (2020). Mirror Ritual: Human–Machine Co-Construction of Emotion. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (697–702). https://doi.org/10.1145/3374920.3375293

Ramm, T. M., Werwie, M., Otto, T., Gloor, P. A., and Salingaros, N. A. (2024). Artificial Intelligence Evaluates How Humans Connect to the Built Environment: A Pilot Study of two Experiments in Biophilia. Sustainability, 16(2), Article 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020868

Savaş, B., Verwijmeren, T., and van Lier, R. (2021). Aesthetic Experience and Creativity in Interactive art. Art and Perception, 9, 167–198. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134913-bja10024

Szubielska, M., Imbir, K., and Szymańska, A. (2021). The Influence of the Physical Context and Knowledge of Artworks on the Aesthetic Experience of Interactive Installations. Current Psychology, 40, 3702–3715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00322-w

Tang, R., Liu, L., Pandey, A., Jiang, Z., Yang, G., Kumar, K., Stenetorp, P., Lin, J., and Ture, F. (2023). What the DAAM: Interpreting Stable Diffusion Using Cross-Attention. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (5644–5659). https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2023.acl-long.310

Taylor, R. P., Micolich, A. P., and Jonas, D. (1999). Fractal Expressionism. Physics World, 12(10), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-7058/12/10/21

Wu, Y., Nakashima, Y., and García, N. (2023). Not Only Generative Art: Stable Diffusion for Content–Style Disentanglement in Art Analysis. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval (199–208). https://doi.org/10.1145/3591106.3592262

Xu, L., Huang, M. H., Shang, X., Yuan, Z., Sun, Y., and Liu, J. (2023). Meta Compositional Referring Expression Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (19478–19487). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01866

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.