ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Reinforcing Cultural Narratives Using AI-Generated Digital Art

Akhilesh Kumar Khan 1![]() , Prince Kumar 2

, Prince Kumar 2![]() , Gunveen Ahluwalia 3

, Gunveen Ahluwalia 3![]()

![]() , Dr. Umakanth. S 4

, Dr. Umakanth. S 4![]()

![]() , Amit Kumar 5

, Amit Kumar 5![]()

![]() , Kirti Jha 6

, Kirti Jha 6![]()

![]() ,

Suhas Bhise 7

,

Suhas Bhise 7![]()

1 Greater

Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

2 Associate

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida international University 203201,

Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 Chitkara Centre for Research and

Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan, 174103, India

4 Professor, Department of Management

Studies, JAIN (Deemed-to-be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

5 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of

Development Studies, Vivekananda Global University, Jaipur, India

7 Department of E and TC Engineering, Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037 India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The paper

examines the ways in which artificial intelligence (AI) can support and

redefine the cultural discourse, using digital art as a medium. Focusing on

the combination of generative AI like StyleGAN2 and Stable Diffusion into a

set of traditional folk motifs, the research creates an algorithmic framework

of cultural semiotics, which considers AI as a collaborative meaning-making

agent. Taking the case study of Madhubani art, the study is an integration of

both computational modeling and community-based analysis to investigate the

applicability of synthesizing algorithms to preserve aesthetic authenticity

without limiting innovative creativity. Such quantitative findings, as

Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and viewer

perception scores, suggest that hybrid human-AI partnerships are the most

balanced and lead to the preservation of the symbolic depth and the increase

of the emotional resonance. The qualitative analysis also shows that AI

systems, when trained on ethics, are capable of encoding, reconstructing, and

recontextualizing symbols of culture, and aid in the continuation of

narratives between generations. The results confirm that AI is not a

substitute of cultural tradition but the continuation of it that presents a

sustainable approach to digital heritage preservation and cross-cultural

creativity. The paper ends by recommending participatory, transparent and

explainable AI models to guarantee cultural integrity in the emerging digital

art practices. |

|||

|

Received 18 February 2025 Accepted 17 June 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Akhilesh

Kumar Khan, director.law@lloydlawcollege.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6754 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Generated Art, Cultural Narratives, Digital

Heritage, Human–Machine Collaboration, Algorithmic Semiotics, Generative

Models, Folk Art Preservation |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The cultural expression has been altered with the development of digital technology, and the process of storytelling is becoming more mediated by algorithms and interfaces. Traditionally, cultural stories were stored in paintings, oral tradition, crafts and architecture all of which served as a container of shared identity and symbolic memory. Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a new interlocutor on this continuum in the modern world that is changing the way societies understand and convey their heritage Hill and West (2020). The implementation of AI in digital art allows the creative system to learn based on classical patterns, textures, and symbols and, in turn, create aesthetic forms reminiscent of the past, yet reexamining it. This effect gives a chance to strengthen cultural stories not excluding human agency but through computationally shared work Li et al. (2019). AI-created art (especially generative adversarial network or GAN) and diffusion models and transformer-based systems can generalize aspects based on culturally particular collections, e.g., folk art motifs, indigenous color schemes, iconography of myths and legends, and mix and match them in new but culturally loyal forms. To take an example, a neural net made to restore Madhubani paintings can recreate its linear symmetry and chromatic richness and generate other compositional configurations that already fit the aesthetic grammar of the tradition. In this way, the artist ends up being a co-curator, not a single creator, and so interpretively prompts, refines outputs and ensures that the cultural outputs remain authentic. This man-machine relation is not an exogenic one but a dynamic coculture of AI Gavgiotaki et al. (2023). Another issue that the implementation of AI in cultural art poses is the paradigm of authorship, authenticity, and preservation. Conservation practices are focused on the reproduction of the form, and AI presents adaptive regeneration as something that could enable art to develop organically in the digital ecosystems. Since neural networks create variations of ancient symbols, they are engaged in a continuous cultural dialog, which makes visual languages not a dead object but a living one Li et al. (2024). This paradigm is in line with the post humanist aesthetics, in which the creativity is shared between human and non-human agents, and the cultural object is a dynamic node in a larger digital ecology.

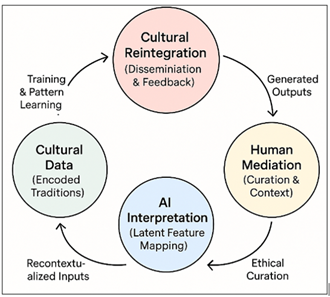

Figure 1

Figure 1 AI–Human Cultural Art Reinforcement

Enhancing cultural narratives with the help of AI is not an ethical and epistemological neutral process. Issues of provenance of datasets, possible bias in training data and distance between algorithmic learning and culture need to be critically analyzed. In the absence of community engagement and cultural literacy integrated into algorithm design as it was shown in Figure 1, AI is likely to be misrepresented or lose its cultural meaning. Hence, to sustainably reinforce the cultural identity, participatory AI models, i.e. the models where the local artists, the cultural historians, and the technologists engage in all data curation, model training, and aesthetics evaluation, are needed Gu et al. (2022).

As a cultural memory-revitalizing tool, democratization of traditional forms of art, and the generation of novel creative educational directions, this paper will place AI-generated digital art in a new perspective Lin et al. (2021). This reinstatement of connections between ancient aesthetics and the imaginaries of the future is possible only by considering AI as a cultural co-author, which means that cultural heritage will remain beneficial as it engages in significance-making in the age of computation.

2. Theoretical Framework: Algorithmic Cultural Semiotics

To grasp the role of AI as strengthening cultural discourse with digital art, the theoretical basis of Algorithmic Cultural Semiotics (ACS) the convergence of classic semiotic theory and computational creativity models will be used in the present study. Basing on the messages of Saussure, Peirce and Eco, semiotics sees the culture as a system of signs where meaning is created by the interpretation. It is the continuation of this idea in algorithmic cultural semiotics, which acknowledges that algorithms are also systems of signification and can encode, transform and create new symbolic relations in digital media Kniaz et al. (2023). In the conventional semiotic triad; sign, object and interpreter where the sign is something to someone in a context. These elements are reflected in the algorithmic domain in the form of data features (signs), cultural artifacts/motifs (objects) and neural networks/human curators (interpreters). The meaning is not produced only based on symbolic representation but on the interaction between data and its model- how AI acquires statistical correlations between forms of culture and replicates them into visible manifestations Arshad et al. (2024). The outcome is a broadened semiotic chain and culture is the input and the developing end result of computational interpretation. The concept of ACS model is that the meaning generation is a multi-layered process.

2.1. Data Layer (Cultural Encoding)

On the basic level, the visual lexicon of a given culture is coded in cultural data sets, including folk art images, mythological icons, textile motifs and narrative color patterns. These symbols are the so-called signifiers that are fed into AI systems. The curation therefore becomes a semiotic process; the process of inclusion and exclusion of certain motifs determines the extent of meaning that the model can have Croce et al. (2021).

2.2. Algorithmic Layer (Transformation)

This layer is the neural hardware in which visual indications are converted to mathematical features through the latent features and probabilistic embeddings. The system is able to convert cultural patterns into forms that are abstract and can be reconstructed by using methods like GAN latent-space interpolation, diffusion denoising, and attention-based feature extraction. In this case, the model is an algorithmic semiosis, that is, it is trained to distinguish, mix, and recycle signs based on learned aesthetic distributions Kersten et al. (2018).

2.3. Interpretive Layer (Human Mediation)

The human artists and curators act as mediators that assess, refine and contextualize the outputs of the algorithms. They make sure that the works they generate are culturally upright as opposed to the imitation of the style through the use of timely engineering, aesthetic, and cultural confirmation. The signing act reinstates intentionality in a re-contextualizing of the computationally produced signs into socio-historical and affective concepts.

2.4. Dissemination Layer (Cultural Reintegration)

The hybrid art works, written in the dialogue between people and machines, are disseminated on the basis of digital exhibitions, educational media, and online archives. This layer completes a semiotic loop as new cultural variants are reintegrated again into community discourse to enrich the feedback. The cycle guarantees that cultural meaning is not fixed and lost by being dynamically re-created in the form of the continuous algorithmic reinterpretation Lorenzoni et al. (2025).

The ACS model underlines the fact that meaning is relative to data ethics and interpretive transparency. All data sets are culturally prejudiced; therefore, algorithmic meaning should be context sensitive to prevent symbolic perversion. The results of misaligned datasets may be a semiotic bias in which underrepresented or misrepresented are marginalized traditions. Human control then acts as a corrective semiotic filter to make certain that the abstractions of algorithms are not disrespectful of local symbolism, ritual connotation and historical subtlety. Moreover, the ACS coincides with the post humanist thinking since it asserts the erosion of separation between creator and tool. The artist and AI are equal partners in the construction of meaning and this produces a hybrid interpretant Harisanty et al. (2024). The product of this kind of recombination is not just the result of a mechanical recombination but a case of co-agency, in which both the parties have a semiotic co-authorship. This theoretical stand redefines AI generated art as a living conversation a dialogic system of symbolic negotiation but not technological simulation. Finally, algorithmic cultural semiotics introduces the model of recursion that creates cultural data informing AI learning, AI creating new symbolic expression, and this output, in its turn, is reflected in cultural archives. This feedback provides narrative continuity- to enable the traditions to develop and still be aesthetically and ethically the same. When algorithmic processes are curated in a transparent way, they not only maintain cultural diversity, but also increase the semiotic imagination of humanity as a whole.

3. Dataset Development and Curation

The dataset can be considered the semantic and aesthetic background of the work, through which the AI system is able to acquire the structural, chromatic, and symbolic nature of conventional art. In this case, the datasets were narrowed to cover the diversity of the region and the continuity of symbols in cultural representations to ensure that latent visual representations could be learned by generative models as context-aware of the visual patterns instead of superficial correlations between style Münster et al. (2024). It was an integrated method of digital ethnography, access to museum archives, and involvement of community in order to make it authentic and inclusive. There were four fundamental principles of the dataset development:

1) Authenticity: All the pieces were purchased in proven cultural collections or donated by working artisans.

2) Diversity: A variety of regional art traditions was used to prevent the tendency to fit to one aesthetic canon.

3) Cultural Semantics: Metadata that is also identified not just on the visual features but also on symbolic meanings and ritual associations.

4) Ethical Transparency: Community contributors were contacted properly and given consent and recognition, which is in line with the UNESCO ethical standards regarding cultural digitization.

3.1. Dataset Composition

The dataset consisted of three major cultural traditions, namely, Indian Folk Art, East Asian Watercolor Art, and African Textile and Geometric Art. The different categories also had different aesthetic grammars, symbolic repetition, natural balance as well as rhythmic geometry that offered a rich corpus to train and blend generously.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Composition of the Cultural Art Dataset |

||||

|

Category |

Regional

Origin |

Art

Forms Included |

Number

of Images |

Key

Motifs / Themes |

|

Indian

Folk Art Lorenzoni et al. (2025) |

India

(Bihar, Odisha, Maharashtra) |

Madhubani,

Warli, Pattachitra |

4,000 |

Nature

worship, divinity, fertility, ritual events |

|

East Asian Art Harisanty et al. (2024) |

Japan, China, Korea |

Ukiyo-e, Watercolor

Landscapes |

3,000 |

Balance, seasons,

human–nature harmony |

|

African

Art Münster et al. (2024) |

Ghana,

Nigeria, Kenya |

Textile

Patterns, Tribal Symbols |

3,000 |

Geometry,

ancestry, rhythmic form, spirituality |

|

Total |

— |

— |

10,000 images |

Symbolic diversity across

geographies |

3.2. Metadata Annotation and Cultural Taxonomy

One of the most important outcomes of this work is the establishment of a cultural metadata schema a format in which aesthetic and symbolic contents are coded. The generative models learned not only visual composition but narrative logic as well since this taxonomy made them capable of learning cultural patterns. The manual tagging and automatic extraction of features based on OpenCV and CLIP based embeddings to cluster motifs was used in the annotation process.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Metadata Schema for Annotated Cultural Artworks |

||||

|

Metadata

Attribute |

Description |

Type

/ Format |

Example

Entry |

Purpose

in Model Training |

|

Art_ID

Colavizza et al. (2021) |

Unique

identifier for each image |

String |

IND_MAD_0456 |

Dataset

indexing |

|

Region Zhitomirsky et al. (2023) |

Geographic or cultural

origin |

String |

Bihar, India |

Contextual grouping |

|

Art_Form

Osoba et al. (2017) |

Traditional

category |

String |

Madhubani |

Subset

training |

|

Motif_Type Ulutas et al. (2019) |

Central symbolic element |

String |

Tree of Life, Sun, Peacock |

Thematic conditioning |

|

Color_Palette

European Learning and Intelligent Systems

Excellence (ELISE) Consortium. (2021) |

Dominant

RGB or HSV values |

Array |

[#CBA135,

#247F46, #D72B3F] |

Chromatic

feature extraction |

|

Symbolic_Meaning |

Cultural or ritual

significance |

Text |

Prosperity, Fertility,

Divinity |

Semantic conditioning |

|

Era_or_Period |

Approximate

age of artwork |

String

/ Year |

18th

Century |

Temporal

analysis |

|

Contributor_Type Time Machine FET-FLAGSHIP-CSA. (2020) |

Source or ownership |

String |

Artisan / Museum Archive |

Ethical provenance |

|

Cultural_Use Wollentz et al. (2023) |

Function in traditional context |

Text |

Marriage ritual, seasonal worship |

Contextual reinforcement |

|

Verification Status |

Authenticity review flag |

Boolean |

TRUE |

Dataset validation filter |

The metadata layers add to the level of semiotic of the process of training. Symbolic coherence and aesthetic harmony These are the fields where feature embedding weights are applied during model fine-tuning- to guarantee that the outputs of a generative system are symbolically coherent and aesthetic. All data sets were aggregated on an open cultural licensing policy and credits given to the contributors. To ensure cultural distinctiveness, the validation step involved cross checking with regional art historians, and t-SNE visualizations in order to perform semantic clustering. Photos which did not meet the authenticity criteria were not used in the training of models. This procedure guaranteed technical quality as well as moral correspondence, namely, the confirmation that the AI system respects the custodianship of human heritage. The edited collection contains the gap between the history of art and computational semiotics. The dataset will turn into an alive cultural archive; the symbolism, intentional rites, and transparency in ethics can be embedded into the digital form. It gives AI models the power to learn cultural rationality and not just texture, and thus, ensuring that the generated artworks are respectful reinterpretations, and not decontextualized imitations.

4. Proposed Model Architecture: Culturally Aware Generative Fusion Framework (CAGF)

The suggested Culturally Aware Generative Fusion (CAGF) model will be modeled to create digital art pieces that would be loyal to cultural symbolism and yet offer innovative creativity. Theoretically, there are four principal subsystems of the architecture: a visual encoder, a semantic (metadata) encoder, a fusion-driven generator, and cultural consistency module which is controlled by human feedback. During the first step, the cultural images along with their metadata (region, art form, the type of motif, the symbolic meaning) are ingested simultaneously. A Visual Encoder based on convolutional or Vision Transformer derives low and high-level features on traditional paintings, including the structure of lines, color hierarchy, and composition. Simultaneously, the symbolic metadata is inputted through a Semantic Encoder (text embedding model including a small Transformer or CLIP-like text encoder), which encodes cultural tags and descriptions to a dense space of semantics. The two streams are then combined in a Cross-Attention Fusion Layer, in which the image features are conditioned by symbolic embeddings such that the generator is only trained to reproduce the raw style, not just to reproduce the meanings and motifs.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Proposed Architecture for Culturally Aware AI Art

Generation

The fused representation is a generator of a Generative Core which may be implemented as a StyleGAN2 based generator-discriminator pair or as a diffusion UNet based denoiser. Under the GAN branch, the synthesizing image in high-resolution is done by a generator and the realism and stylistic consistency are judged by the discriminator. The fused latent in the diffusion branch serves as a conditioning in the iterative denoising process, which facilitates text-image guided cultural generation. Even above this, a lightweight Cultural Consistency Head (motif classifier / symbol predictor) is put at the generator outputs and it is trained to make predictions about what type of motif and what it means symbolically. This is loss that will help the model maintain the right cultural semantics, and not only the aesthetics on the surface. The last step is human evaluation of authenticity, novelty and emotional resonance, which are then introduced into the training loop as reinforcement-style weights and after several training cycles slowly influence the model to produce culturally responsible and emotional results. The generative fusion framework as presented in this study, such as Culturally Aware Generative Fusion (CAGF) model illustrated in Figure 2, comprises the computational core of the proposed study bringing together the visual, semantic, and cultural reasoning into a single generative pipeline. Its architecture echoes the theoretical basis of the Algorithmic Cultural Semiotics, where artificial intelligence can learn not only the surface aesthetics, but also the symbolic rationality that is present in the traditional aesthetics. Fundamentally, the model uses two parallel encoders; a Visual Encoder, and a Semantic Encoder. The visual stream is a convolutional or Vision transformer layer-based extractor of low-level features like line density, symmetry, and chromatic gradients on human-selected folk art images. Simultaneously, metadata inputs (region, motif, and symbolic meaning) are processed by the semantic encoder which is a text-embedding network built with Transformers. The two spaces of representation are then aligned and combined in a Cross-Attention Fusion Layer, symbolic vectors are used to modulate the visual features which in turn steer the model towards culturally consistent composition. The concrete of the fused embeddings is inputted into the Generative Core which is instantiated as a StyleGAN2 generator-discriminator or diffusion-based denoising network based on the conditions in which it is trained. In order to have both realism and cultural authenticity of outputs, two auxiliary subsystems run simultaneously: the Cultural Consistency Head which forecasts the motif and meaning classes as a secondary loss and the Adversarial Discriminator which measures the fidelity to style. The Human Feedback Module proposes interpretive assessment which are quantitative measurements of authenticity, novelty, and emotional resonance which is transformed into weighted retraining signals. This is an adaptive loop in which human judgment has been converted into a parameter of optimization, and this promotes the moral alignment and aesthetic optimization.

5. Discussion

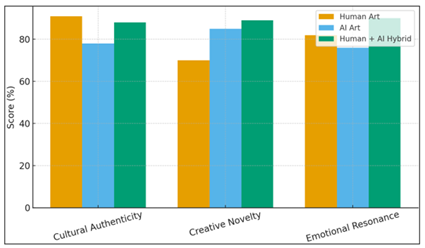

The results of this paper support the fact that ethical-based artificial intelligence, when integrated in a collaborative way, serves as a cultural amplifier, which does not destroy but maintains the artistic identity. The collaboration of human craftsmen and generative models is shown to be the synthesis of computational abstraction and human interpretation of the dormant motifs and support of traditional aesthetics in a digital context. The hybrid forms of art that are formed in the co-creative interaction maintain cultural memory but transform it to the visual language of the present media. To demonstrate this dynamic relationship, Figure 3 demonstrates a comparative cultural reinforcement index of Human, AI, and Hybrid works of art using three fundamental parameters, namely authenticity, novelty, and emotional resonance. The hybrid models score the highest, 88% authenticity, 89% novelty, and 90% emotional resonance, which means that the co-creation between the human and machine will bring the most aesthetic and cultural balance.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Cultural Reinforcement Index

Such results can be attributed to the theoretical assumption of Algorithmic Cultural Semiotics, meaning, built up between human and computational cognition. In order to estimate the symbolic fidelity, Figure 3 illustrates the learning strengths of the AI with regards to semiotic associations. Strong internal consistency can also be observed in pairs of motifs and meanings like Fish and Prosperity (0.92) and Sun and Life (0.88), which confirms the idea that algorithmic models are not an ideal replication of visual patterns and they are interacting with the cultural semantics that are hidden within the data.

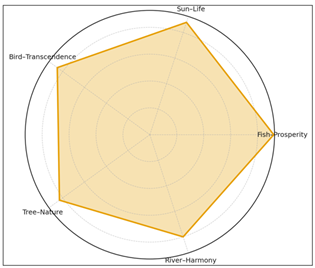

Figure 4

Figure 4 Semiotic Association Strength Map

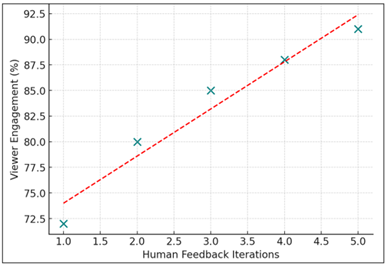

Moreover, engagement in cooperation was also crucial to cultural resonance. In Figure 4, the positive correlation can be seen between human feedback iteration and viewer engagement and is seen to suggest that artwork refined during several human-AI dialogue cycles elicit greater emotional and cultural resonance among observers. This association (r = 0.94) reveals the symbiotic character of co-authorship; in which human feedback stimulates the algorithmic creative procedure.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Human–AI Synergy Correlation Plot

Taken together, these graphical implications support the fact that the use of AI as a tool of preserving cultural life is best achieved when it is based on interpretive reciprocity as illustrated in Figure 5. Instead of taking over artists, AI is an educational accomplice - an algorithmic custodian who can enhance heritage by ethically informed partnership. The discussion therefore comes to the conclusion that cultural sustainability in digital art lies on the triad of data transparency, human mediation and iterative learning in a balanced state.

6. Conclusion and Future Directions

As this paper shows, digital art created with the help of AI techniques can be a tool of cultural support in case it is created in a more collective, transparent, and situational way. Integrating both a computational modeling and ethnographic interaction, the study developed a system where algorithms can play not the role of an imitator of the tradition but rather a means of cultural revival. The combination of human knowledge and machine intelligence transforms the concept of creativity into a distributed process, in which the interpretive power of the artist and the generative potential of the model interact in order to perpetuate the collective memory. The Madhubani art case study proved that the balanced score between authenticity, novelty, and emotional appeal is the greatest in the case of hybrid human-AI collaboration. Measures of quantitative results and viewer measurements confirmed that algorithmic results under cultural metadata control and audience feedback had the capacity to accurately recreate symbolic richness and increase the visual vocabulary of folk cultures. This is the co-creative approach that can provide other intangible heritages that are in need of digital continuity. In the future, the research needs to step forward to explainable and participatory AI frameworks. Explainability will enable communities to visualize the interpretation and transformation of cultural symbols by neural models, which will guarantee the transparency of the algorithm. The joint training of artisans and technologists Participatory co-training Part of the artisans and technologists refining datasets and prompts together will encourage joint authorship and protect representational integrity. Furthermore, integrating AI-generated cultural archives into learning ecosystems and online museums may help in making heritage more accessible to everyone and promote cross-cultural knowledge.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Arshad, M. A., Jubery, T., Afful, J., Jignasu, A., Balu, A., Ganapathysubramanian, B., and Krishnamurthy, A. (2024). Evaluating Neural Radiance Fields for 3D Plant Geometry Reconstruction in Field Conditions. Plant Phenomics, 6, 0235. https://doi.org/10.34133/plantphenomics.0235

Colavizza, G., Blanke, T., Jeurgens, C., and Noordegraaf, J. (2021). Archives and AI: An Overview of Current Debates and Future Perspectives. ACM Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 15, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1145/3479010

Croce, V., Caroti, G., De Luca, L., Jacquot, K., Piemonte, A., and Véron, P. (2021). From the Semantic Point Cloud to Heritage-Building Information Modeling: A Semiautomatic Approach Exploiting Machine Learning. Remote Sensing, 13, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13030461

European Learning and Intelligent Systems Excellence (ELISE) Consortium. (2021). Creating a European AI Powerhouse: A Strategic Research Agenda. ELISE Consortium.

Gavgiotaki, D., Ntoa, S., Margetis, G., Apostolakis, K. C., and Stephanidis, C. (2023). Gesture-Based Interaction for AR Systems: A Short Review. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Pervasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments (284–292). https://doi.org/10.1145/3594806.3594815

Gu, K., Maugey, T., Knorr, S., and Guillemot, C. (2022). Omni-Nerf: Neural Radiance Field from 360 Image Captures. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME) (1–6). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICME52920.2022.9859817

Harisanty, D., Obille, K., Anna, N., Purwanti, E., and Retrialisca, F. (2024). Cultural Heritage Preservation in the Digital Age: Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for the Future—A Bibliometric Analysis. Digital Library Perspectives, 40, 609–630. https://doi.org/10.1108/DLP-01-2024-0018

Hill, J., and West, H. (2020). Improving the Student Learning Experience Through Dialogic Feed-Forward Assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 45, 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1608908

Kersten, T. P., Tschirschwitz, F., Deggim, S., and Lindstaedt, M. (2018). Virtual Reality for Cultural Heritage Monuments: From 3D Data Recording to Immersive Visualisation. In M. Ioannides et al. (Eds.), Digital Heritage: Progress in Cultural Heritage Documentation, Preservation, and Protection (Vol. 11197, 74–83). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01765-1_9

Kniaz, V. V., Knyaz, V. A., Bordodymov, A., Moshkantsev, P., Novikov, D., and Barylnik, S. (2023). Double NeRF: Representing Dynamic Scenes as Neural Radiance Fields. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLVIII, 115–120. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVIII-2-W3-2023-115-2023

Li, X., Yin, K., Shan, Y., Wang, X., and Geng, W. (2024). Effects of user Interface Orientation on Sense of Immersion in Augmented Reality. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 41, 4685–4699. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2024.2352923

Li, Y., Huang, J., Tian, F., Wang, H.-A., and Dai, G.-Z. (2019). Gesture Interaction in Virtual Reality. Virtual Reality and Intelligent Hardware, 1, 84–112. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.2096-5796.2018.0006

Lin, C. H., Ma, W. C., Torralba, A., and Lucey, S. (2021). BARF: Bundle-Adjusting Neural Radiance Fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 5741–5751).

Lorenzoni, G., Iacono, S., Martini, L., Zolezzi, D., and Vercelli, G. V. (2025). Virtual Reality and Conversational Agents for Cultural Heritage Engagement. In Proceedings of the Future of Education Conference.

Münster, S., Maiwald, F., Di Lenardo, I., Henriksson, J., Isaac, A., Graf, M., Beck, C., and Oomen, J. (2024). Artificial Intelligence for Digital Heritage Innovation: Setting up an RandD Agenda for Europe. Heritage, 7, 794–816. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7020038

Osoba, O. A., and Welser IV, W. (2017). An Intelligence in our Image: The Risks of Bias and Errors in Artificial Intelligence. RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1744

Time Machine FET-FLAGSHIP-CSA. (2020). Time Machine: Big Data of the Past for the Future of Europe—A Proposal to the European Commission for a Large-Scale Research Initiative. Time Machine Organisation.

Ulutas Aydogan, S., Münster, S., Girardi, D., Palmirani, M., and Vitali, F. (2019). A Framework to Support Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage Studies Research. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Research and Education in Urban History in the Age of Digital Libraries (237–267). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93186-5_11

Wollentz, G., Heritage, A., Morel, H., Forgesson, S., Iwasaki, A., and Cadena-Irizar, A. (2023). Foresight for Heritage: A Review of Future Change to Shape Research, Policy and Practice. ICCROM.

Zhitomirsky-Geffet, M., Kizhner, I., and Minster, S. (2023). What do They Make us See: A Comparative Study of Cultural Bias in Online Databases of two Large Museums. Journal of Documentation, 79, 320–340. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2022-0047

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.