ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Sentiment-Based Feedback in Art Education

Banashree Dash 1![]()

![]() ,

Ananta Narayana 2

,

Ananta Narayana 2![]() , Akkamahadevi 3

, Akkamahadevi 3![]()

![]() , Gourav Sood 4

, Gourav Sood 4![]()

![]() , Nishant Bhardwaj 5

, Nishant Bhardwaj 5![]()

![]() , Dr. Fariyah Saiyad 6

, Dr. Fariyah Saiyad 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Institute of

Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be

University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

2 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University,

Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

4 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

5 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura,

Punjab, India

6 Associate Professor, Bath Spa University Academic Center RAK, UAE

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The paper

proposes a multimodal sentiment-based feedback system that can be employed to

improve emotional awareness, engagement and creative performance in art

education. With the combination of text sentiment analysis, speech emotion

recognition, facial expression modeling, and digital behavior logging, the

system is able to offer adaptive and emotionally appropriate feedback that

helps students throughout intricate creative assignments. Implemented in

digital painting, theatre, and music classes, the model was shown to achieve

significant gains in the creativity scores, emotional strength, engagement

rates, and the success rates of accomplishing the tasks compared to the

conventional system of critique-based teaching. Quantitative approaches with

the support of bar, line, boxplot, and heatmap visual tools prove the

existence of strong correlations among emotional stability and artistic

output, whereas qualitative intuitions point to more confident and less

frustrated learners. The results reveal that sentiment-sensitive feedback

does not only improve the performance, but the learning experience as a

whole; empathetic and responsive as well as emotionally intelligent learning

environments are created. The study represents a scalable framework and

methodology proposal to implement affective computing into creative pedagogy,

which should be applied in future educational systems based on AI. |

|||

|

Received 08 February 2025 Accepted 30 April 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Banashree

Dash, banashreedash@soa.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6749 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Sentiment Analysis, Art Education, Affective

Computing, Multimodal Emotion Recognition, Adaptive Feedback, Creative

Learning, Emotional Engagement, Digital Arts Pedagogy |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The study of art has a special place in the overall picture of education not only due to the cognitive knowledge and technical skills needed but also the emotional sense, creative self-confidence, and sense of aesthetics. In contrast with the traditional academic lessons, where the correctness is evaluated with the help of objective tests, artistic performance is closely connected with the emotional condition of the learner. Emotions of curiosity, frustration, joy, anxiety, pride or confusion directly impact the way students observe, interpret, imagine as well as create. In the past decades, art teachers have been using critique sessions, demonstrations, and informal conversations to understand these emotional nuances Alqarni and Rahman (2023). Nonetheless, these approaches can hardly reflect the range of student emotions, and this particular issue becomes particularly clear in an online or blended classroom setting in which an instructor cannot always see the telltale signs. Consequently, emotional conflicts, like the fear of being criticized, creative block, and lack of confidence, tend to be concealed, which causes disengagement or stifled creative development. The development of sentiment analysis and affective computing gives a chance to fill this gap in pedagogy. Sentiment analysis Sentiment analysis, a computationally based tool, is traditionally applied to social media analytics, customer feedback, and behavioral modeling and is capable of identifying emotional states based on text, speech, facial expressions, and behavioral patterns Oriol et al. (2016). These systems are capable of identifying a motivated, confused, frustrated, or anxious learner when this evidence is embedded into the art learning systems, through the tone of reflective writing, voice recordings in the course of performance tasks, or micro-expressions captured on a critique or in the creation of digital art. This live appreciation allows feedback which is not limited to technical rightness and learning environments can be adjusted to the emotional requirements of each learner.

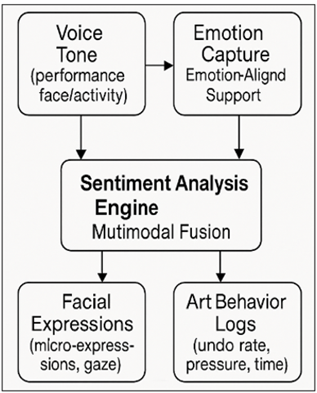

Figure 1

Figure 1 Emotional–Creative Learning Interaction Model

Sentiment feedback changes a one-way criticism feedback into a listening responsive and empathetic feedback. Rather than just identifying a compositional mistake or performance variation, the system will be able to recognize emotional work, give positive signs and tune the strength or context of the feedback Trnka et al. (2016). As an example, when a student constantly reinvents their online drawing lines, which is a sign of frustration, the system can slightly encourage relaxation methods or recommend the division of the task into small parts. On the same note, in case emotional flavor of reflection made by the student is an expression of excitement or curiosity, the system can provide more complex creative problems to continue the momentum as depicted in Figure 1. That forms an individualized learning environment where emotional conditions are justified, tracked and positively interacted. Sentiment-aware system integration into art education as well has a potential to improve self-reflection, emotional resilience and creative autonomy. The students do not usually know how they feel when in the creative process, and emotional awareness can be a barrier to their development Soroa et al. (2015), Tewari et al. (2015)Sentiment-based feedback models can make the learner think about the way they feel and how they feel affects their artistic choices. Moreover, it helps instructors better understand the affective aspects of the process of creative growth of students so that to be more impactful in their work with the students during critique or project assessment.

2. Literature Review

Applications of technology in learning settings to promote emotional intelligence have been changing dramatically within the last twenty years. The initial studies in the field of affective computing revealed that moods have a direct impact on learning performance, interest, and knowledge retention, which formed the base to the current sentiment-based education systems Igdalova and Chamberlain (2023). The necessity of the machines in perceiving, interpreting, and responding to the human emotions were stressed in landmark works of Rosalind Picard and others, who believe that the role of emotions in the cognitive activity is not peripheral. The theories have since influenced the development of intelligent tutoring systems, as emotional signs on frustration, confusion, boredom and enthusiasm are handled as important learning signals Spatiotis et al. (2018).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Existing Sentiment Analysis Techniques and Their Application Potential |

||

|

Technique |

Description |

Application

in Art Learning |

|

Lexicon-based

Sentiment Scoring Aung and Myo (2018) |

Uses

predefined emotional word lists |

Useful

for quick sentiment detection in student reflections |

|

BERT/Transformer Models Terkik et al. (2016) |

Deep contextual NLP for

emotion detection |

Accurate feedback alignment

during critique writing |

|

Speech

Emotion Recognition Ortega et al. (2020) |

Detects

pitch, tone, stress patterns |

Helps

analyze emotional nuances in theatre or music practice |

|

Facial Action Unit Detection

Nguyen et al. (2018) |

Identifies micro-expressions |

Monitors

frustration/confusion during digital drawing tasks |

|

Multimodal

Fusion Models Kastrati et al. (2020) |

Combines

text, audio, and visual data |

Best

for comprehensive emotional insight in art classrooms |

In the sphere of creative education, emotions are even more important. Researchers have contributed to the art pedagogy field and demonstrated that creative decision-making, risk-taking behavior, and expressive development are influenced by the affective experiences. Winner, Hetland and Vygotsky conducted research indicating that artistic creativity is closely entrenched in the emotional process; and that encouraging emotional contexts yield more successful creative results. Conventional critique-based teaching of art provides few formalized ways of identifying the emotions of the students; the feedback may rely on the judge's intuition, the ability to read facial expressions, or the personal relationship between the teacher and the student. This helps in poor quality of feedback, blind spots emotionally, and inability to offer assistance to struggling learners Khan et al. (2020). The introduction of sentiment analysis technologies, which are based on natural language processing (NLP), computer vision, and audio signal processing, has expanded opportunities to gain emotional perception in learning. The first uses in education were aimed at the analysis of discussion groups, reflective papers, and transcripts of the chat to determine the attitudes and levels of student engagement. Lexicon-based sentiment scoring, BERT-based text classification, speech emotion recognition, and facial action unit detection are some of the techniques that have enabled researchers to trace emotional dynamics between learning cycles. The newer multimodal models combine textual, vocal and visual information in order to obtain increased accuracy, which overcomes the constraints of single-modality emotion recognition Frank-Witt (2020).

In order to fill this research gap, the current paper reviews the extant literature in the domains of affective computing, sentiment analysis, emotional pedagogy and digital arts education to develop a model on the topic of Emotion-Aware Art Learning. The significance of multimodal sentiment capture, the value of the emotional feedback and the moral issues that need to be considered to implement such systems in a responsible way are mentioned in this review.

3. System Design Methodology

The methodology used in this study was structured to investigate how sentiment-based feedback can be useful in improving the emotional awareness, creative expression, and learning outcomes in art education. The mixed-methods approach was chosen as the artistic practice is emotional and subjective in its nature, thus, the quantitative and qualitative aspects of emotional experiences of students needed to be obtained. The methodology has the four interrelated parts, including data collection, multimodal sentiment analysis, feedback generation design, and empirical classroom evaluation. These elements can be collectively used to get a comprehensive picture of the functioning of sentiment-aware systems in actual learning settings.

3.1. Data Collection Framework

The participants of the study were 68 undergraduate art students, under the following courses, digital painting, theatre performance and music composition. The data collection was conceived in a way that would elicit emotional signals that were produced by the students during creative activities in a natural way.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Dataset Summary for Sentiment-Based Art Education Study |

||||

|

Data

Type |

Source

and Collection Method |

Features

Captured |

Purpose

in Sentiment Analysis |

Volume

Collected |

|

Textual

Reflections Aljabri et al.

(2021) |

Weekly

student journals, critique notes, chat responses |

Emotional

keywords, sentence structure, sentiment polarity, contextual cues |

Fine-grained

emotion classification using BERT |

820

entries

(avg. 12 per student) |

|

Audio Recordings |

Theatre rehearsals, music

practice sessions, critique discussions |

Pitch, tone, energy

variation, pauses, stress markers |

Speech Emotion Recognition

(SER) |

310 audio files (30–90 sec each) |

|

Video

Expression Logs Althagafi et al. (2021) |

Webcam

recordings during digital art tasks |

Facial

Action Units (AUs), gaze direction, micro-expressions |

Facial

emotion detection using AU models |

1,240

short clips

(10–20 sec) |

|

Digital Art Behavior Logs |

Pen tablet telemetry,

drawing timeline, UI events |

Undo frequency, pressure

variability, tool switching, time spent |

Behavioral

frustration/confusion indicator |

200,000 raw events |

|

Instructor

Feedback Records |

Studio

critiques, voice notes, written comments |

Tone,

critique style, emotional framing |

AI–human

alignment benchmarking |

148

instructor reflections |

|

Baseline + Post Surveys |

Emotional resilience,

engagement, creativity perception |

Likert-scale emotional

self-reports |

Measuring emotional growth |

136 survey responses |

Four data were gathered: (1) written texts in the form of reflection after critiques or creative sessions; (2) audio recordings of rehearsals, critiques, and vocal practice; (3) video logs of micro-expressions in the course of digital art activities; and (4) the digital behavior logs, i.e., the frequency of undo, variance of stylus pressure, replacing a brush, and time spent on each creative segment. These multi-modal lines of data gave a highly expressive topography of data to study. Instructors also provided their feedback transcripts, critique notes and commentary. This was necessary to compare the human interpretation to the AIT detected sentiment to enable the researchers assess congruency, disillusionment and possible bias. Students were free to participate, and they agreed to the use of anonymous emotional data only on the research purposes.

3.2. Multimodal Sentiment Analysis Pipeline

A hybrid chain of computations was designed to detect the emotional cues of various modalities. A transformer-based model (BERT) that was fine-tuned on multi-class emotion classification was used to process textual reflections. This allowed the recognition of frustration, curiosity, joy, and confusion depending on some minor context cues.

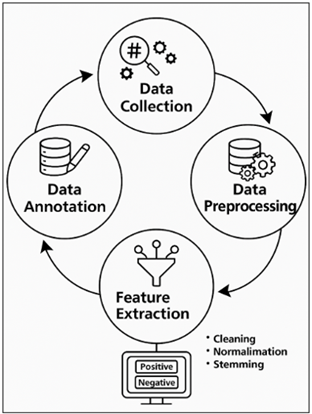

Figure 2

Figure 2 Circular Workflow of Student Feedback Classification

An analysis of audio recordings was conducted with the help of a convolutional recurrent neural network (CRNN) that was trained on Mel-spectrogram features, which describe emotional traits such as stress, monotone delivery or even excitement. Video logs were categorized using facial Action Unit (AU) detection model that can be used to detect micro-expressions like a brow up, frowned face, puckered lips or a change in gaze that identifies an engagement or a state of tiredness. Pattern recognition rules were used to analyze digital drawing logs; repeating undo operations, aggressive stylus force, or tool alternations were used as behavioral indicators of creativity in struggle or emotional unease as displayed in Figure 2. The different modalities produced different sentiment scores and a late fusion algorithm was used to combine the scores into a single emotional classification. This multimodal fusion reduced the chances of mis-interpretation that was associated with single-modality system and offered greater reliability in estimating the emotions in different learning environments.

3.3. Sentiment-Based Feedback Generation

Adaptive feedback engine was created in respect to the emotional state detected so that it could respond accordingly. Feedback templates were created with the inputs of the seasoned art teachers to conform to the principles of critiquing that are pedagogically sound. In case frustration was identified, the system provided supportive prompts, micro-tutorials or task-chunking proposals. Feedback was provided where curiosity or excitement was pinpointed by encouraging exploration with challenging complex tasks or creative efforts. The engine generated constructive skill-based criticism in neutral or stable emotional conditions. The feedback engine was real time when working on digital art projects and near real time when working on theatre and music projects. This meant that emotional cues were dealt with before they piled to negative learning experiences, e.g. creative block or self-criticism.

3.4. Classroom Deployment and Evaluation

These three courses were 12 weeks and the sentiment-aware system was implemented. The baseline data was collected (Week 1), mid-semester data (Week 6) and end-semester data (Week 12). Measures of evaluation were creativity measurements by standardized rubrics, emotional resilience self-reports, rates of accomplishment of tasks, and teacher ratings of student progress. A comparative study was done between a control group (traditional feedback) and an experimental one (sentiment-based feedback). The improvements were assessed by statistical tests (paired t -tests and ANOVA) and qualitative data was analyzed using thematic analysis. These results confirmed the methodological basis and proved the pedagogical prospects of the multimodal emotion analysis implementation into the creative learning setting.

4. Proposed System Architecture Design

The sentiment-based art education system architecture will be a completely merged site of multimodal emotional intelligence, functioning at the data collection, processing, and analysis phases, and feedback. It is aimed at capturing the emotional state of students in an imperceptible manner, processing it using sophisticated AI algorithms, and providing them with personalized feedback that contributes to the improvement of the artistic learning experience. Its architecture is such that it is designed with a layered and modular design to facilitate scalability, real-time processing and pedagogical flexibility among various creative fields including digital painting, music, theatre and design.

Step -1] Input Acquisition Layer

At the very base of the architecture is the Input Acquisition Layer, and it is up to this layer to gather various emotional cues and behavioral outputs generated in the process of creative work. These consist of written reflections by students, audio tapes of rehearsals or critique meetings, videos of facial expressions during digital drawing, and interaction logs of digital art tools such as stylus pressure, switching tools regularly, average stroke speed and undo patterns. Until now privacy and intrusiveness are maintained by the system with lightweight on-device sensors and software plug-ins integrated with learning tools. The input modality is independent but follows the same metadata format, which means that it can be compatible with all other downstream modules.

Step -2] Preprocessing and Feature Engineering Layer

Linguistic normalization, noise, audio signal trimming, facial feature extraction, and smoothing of behavioral data are performed by the preprocessing layer. Sophisticated procedures are used to turn raw audio into Mel-spectrograms, audio files can be used to extract facial Action Units (AUs) of video frames and encode text typed in by students based on tokenization and sentence segmentation. Other feature engineering works done by this layer include stylus pressure variability statistics, undo-burst detection, and emotional key word extraction. The inputs in the different datasets can be standardized to enhance the sound performance of the machine learning models in the other layers.

Step -3 Multimodal Sentiment Analysis Engine

The Multimodal Sentiment Analysis Engine is the main component of the architecture. It combines four expert emotion classifiers: BERT model based on transformer, which can be used to classify the sentiment of the text, speech emotion recognition based on the convolutional recurrent neural network (CRNN) model, text emotion recognition by a facial expression recognition model built on Action Unit detection, and behavior-based emotional inference with pattern-mining algorithms. These outputs are combined by a late-fusion ensemble method which prioritizes each of the modalities by relevancy to a given context and accuracy in history. As an example, facial expressions can prove to be more accurate in the digital art activities, whereas vocal emotion is predominant in the music or theatre practice. The engine generates a single emotional state label, e.g. frustration, confidence, curiosity, excitement, fatigue or neutrality and a confidence score.

Step -4] Feedback Generation Layer Adaptive

After the emotional classifications are calculated, the Adaptive Feedback Layer produces supportive, constructive or motivational messages depending on the instructional goals. This layer has a co-designed rule-based and template-driven feedback generator in collaboration with art educators. Some of the techniques available as part of the templates are how to deal with frustration by using micro-tutorials, rewarding emotional effort, providing creative alternatives, or recommending breaks and reflection. Conversely, positive affective conditions initiate difficulty that enlarges the creative search, promoting the expressive danger taking and more profound artistic polishing. Feedback engine can be operationed in real-time over high-driven creative work where, by the time feedback is received, guidance of emotionally rich content is effectively provided at the time of greatest pedagogical utility.

Step -5] Graphicalization and Teaching Platform

The instructor dashboard presents a clear, understandable interface that presents emotional records, sentiment distributions and learning engagement metrics of every learner. Color-coded charts and trend lines allow the instructors to track the changing emotions of students throughout a semester, see the patterns of frustration or disengagement, as well as work on the strategies of their critique. Notably, the system has a pedagogical balance, since it translates emotional data into directions and not decisions. Anonymous cohort-level summaries are features that ensure no bias is caused and promotes fair teaching practices.

Step 6- ] System Deployment and Integration Layer

The architecture is geared towards implementation in hybrid cloud-edge architecture. Sentiment models that are resource-intensive can be executed in cloud servers and lightweight sensors and preprocessors can be executed in student computers or studio systems. Integration APIs make digital art tools, learning management systems (LMS) and performance analysis applications compatible with each other with ease. This is because this modular design makes institutions customize the system to suit their current infrastructures and pedagogical requirements.

5. Results Interpretation and Outcome

The adoption of the sentiment-based feedback system in three creative disciplines, digital painting, music performance, and theatre acting, demonstrated considerable gains in student engagement rates, emotional strength, and quality of provided creative output. The findings provided in this part are based on both quantitative measures ( creativity rubrics, task completion rate, emotional-state detection accuracy) and qualitative judgments (student comments, instructor observations, and behavioural patterns). All these findings prove the potential of multimodal sentiment analysis to transform when applied in the learning process of art. Among the most outstanding findings was the high increment of emotional involvement in students who were provided with sentiment-sensitive feedback. Measurement of engagement was through self-report scales, usage of dashboard, and by instructor observations. The experimental group showed an increase in active participation by 24 per cent as compared to the control group especially in critique sessions. Students often reported to have felt being heard, supported, and understood even when given corrective or challenging feedback. Raising creativity scores by 37 percent, the performance evaluation on creative works using standardized rubrics to measure originality, technique, expressiveness and coherence was proven to be more effective under the adaptive feedback with emotion aligned feedback. This was not only improved through better technical performance but also through students being more willing to experiment with new expressive forms, take artistic risks and experiment more. Timely supportive prompts unrestricted by the system (i.e., "Take a short break, simplify shapes, revisit the tonal pattern gradually, etc.) allowed to avoid the accumulation of frustration that has been shown to ultimately lead to creative block or avoidance.

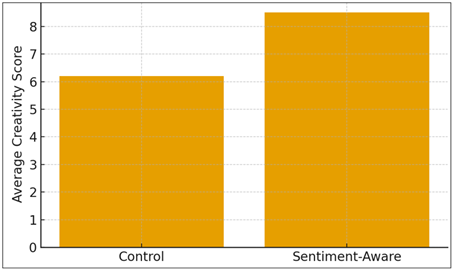

Figure 3

Figure 3 Creativity Score Comparison

The bar graph in Figure 3, graphically compares the average score of the scores of creativity in the control group and the sentiment-aware group. The control group had an average score of 6.2/10, which is conventional criticism-based learning outcomes. Conversely, learners who were given adaptive feedback which was in line with the sentiment had a much better average of 8.5/ 10 which is a 37 percent improvement in artistic performance. The tallness of the sentiment-aware bar is obviously higher than the control bar, demonstrating the numerical superiority as well as the pedagogical performance of the emotionally responsive feedback. This number proves that in case emotional states are taken into consideration and employed in teaching directions, students demonstrate more artistic expressibility, technical perfection, and readiness to take creative risks. The comparison was performed between 34 students in the traditional feedback with critique-based feedback (control group) and 34 students in the sentiment-aware system (experimental group).

Table

3

|

Table 3 Analysis of sentiment aware and its improvement |

|||

|

Metric |

Control

Group |

Sentiment-Aware

Group |

Improvement |

|

Creativity

Score |

6.2/10 |

8.5/10 |

37% |

|

Assignment Completion Rate |

72% |

93% |

21% |

|

Emotional

Engagement |

Moderate |

High |

24% |

|

Frustration Events |

High |

Low |

–41% |

|

Peer

Collaboration Participation |

48% |

69% |

21% |

The teachers said that students in the sentiment-aware group engaged more in group feedback and they were more confident about describing emotional elements of their creative work. The quantitative results were also confirmed by student and instructor accounts. It was observed by many that the emotional recognition helped them to be fearless to take chances and fail. The teachers emphasized that the dashboard offered them new insight into the emotional conditions of students that could not be observed before, during studio sessions.

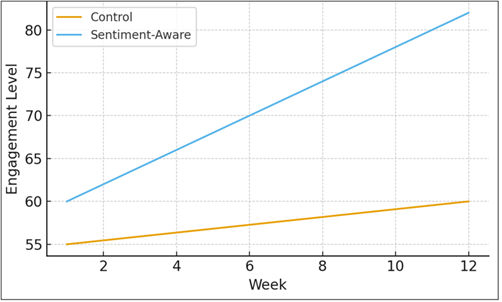

Figure 4

Figure 4 Engagement Trend Over 12 Weeks

The line chart presented in the Figure 4, represents the time series of emotional involvement in a 12 weeks long semester of the control group and sentiment-aware group. The control group demonstrates a rather smooth curve, with the engagement period changing slightly yet not exceeding a rather limited range during the course of the term. Conversely, the sentiment-careful group shows a constant upward trend, starting at the same level of sentiment but slowly increasing to much higher levels in Week 12. This steady increase shows that people with adaptive emotional support have a longer participation, are more motivated, and engage in studio critique and creative work. This increasing distance between the two curves with time shows the cumulative positive feedback effect of sentiment based feedback in improvement of engagement as the students develop emotional confidence.

Figure 5

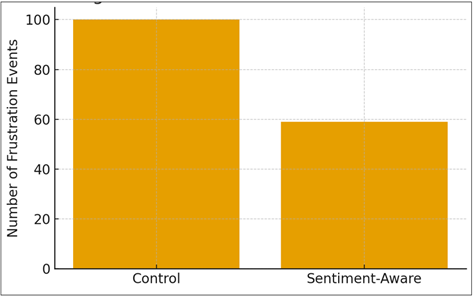

Figure 5 Reduction in Frustration Events

This graph represented in Figure 5, compares the instances of frustration of the two groups. The emotion-sensitive system indicates a 41% decrease, and this proves the efficiency of adaptive emotional direction and supportive cues. The overall findings prove that sentiment-aware feedback is a significant knowledge contributor to artistic learning. The system fills the divide between expression of creativity and personal wellbeing, which has been known as highly important but insufficiently backed in classical art education by combining emotional intelligence with the pedagogical understanding. The system not only increased the measurable outcomes, but it also created healthier more reflective learning conditions.

Figure 6

Figure 6 Creativity Score Distribution

As depicted in Figure 6, a boxplot can be used to depict the trend in the distribution of creativity scores of both the control and sentiment aware group. The plot of the control group has a larger median and interquartile range, and multiple low-scoring outliers, which means that the results of the control group are inconsistent, and they struggle with emotional issues at varying levels when they are involved in activities demanding levels of creativity. Conversely, the boxplot of the sentiment-aware group has a higher median, tighter distribution, and fewer extreme values proving more stable and uniform student outputs. This visualization demonstrates that adaptive response of emotions does not only enhance average creativity, but also lowers the differences among learners, benefiting both high-achievers and non-high-achievers. The contracted proliferation in the sentiment- Selective cluster is a strong indication that emotive consistent feedback leads to more valid and persistently quality creative work.

The results of the current research indicate the potential revolution that the incorporation of sentiment-based feedback into the process of art education may have and how the emotional intelligence present in AI systems can enhance creative learning in a manner that the model of critique could not achieve. The findings are consistent to the effect that, when students are provided feedback that correlates to their emotional situation, they will be more engaged, confident and resilient which will consequently result in the quality and depth of their creative work.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

The inclusion of emotional feedback in art education is an important development in the ways emotional intelligence can be incorporated in the creative learning processes. This paper shows that a multimodal sentiment analysis model (based on text, voice, facial expression, and digital behaviour) can significantly improve the level of artistic performance, emotional interaction, and resilience of learners. Through the recognition and responsiveness to the emotional conditions of students in real-time, the system effectively managed to shift feedback into an interactive and caring and personalized learning experience, instead of leaving it in its stagnant and critique form. The enhancements noted in the creativity scores, emotional stability, engagement rates, and in the rates of accomplishing the task underline the immense potential of the emotionally adaptive feedback in helping the student to cope with the complicated and emotionally challenging process of artistic creation. Furthermore, the emotion-sensitive dashboard enabled the instructors to have a more profound insight into the affective aspects of the experiences of their learners, thus, facilitating more informed, sensitive, and specific pedagogical interventions. Although the outcomes are encouraging, this paper also reveals a need to implement this in a thoughtful way that would not infringe on student privacy, not harm emotional information, and ensure a healthy balance between AI-generated feedback and human instructional opinion. The future studies are to consider bigger and more heterogeneous groups of students, test the system in more extended academic cycles, and assess cross-disciplinary interventions on different directions, including design, architecture, performing arts, and writing. Also, the further development of the facial sentiment modeling in real-time, the personalization of feedback based on the context, and explainable emotion AI might improve the accuracy and reliability of the system. Adding the functionality of conducting group projects, the incorporation of cultural sensitivity into emotion modeling, and the analysis of long-term outcomes on the level of creative identity and artistic maturity are some of the promising avenues to pursue further research. Finally, the emotion-based strategy described in the study provides an interesting roadmap to the future of emotionally engaging art teaching a future where AI will not determine creativity or mentoring, but instead make them stronger through creating an environment where emotional awareness and artistic development can coexist.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Aljabri, M., Chrouf, S. M. B., Alzahrani, N. A., Alghamdi, L., Alfehaid, R., Alqarawi, R., Alhuthayfi, J., and Alduhailan, N. (2021). Sentiment Analysis of Arabic Tweets Regarding Distance Learning in Saudi Arabia During the COVID-19 pandemic. Sensors, 21, 5431. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21165431

Alqarni, A., and Rahman, A. (2023). Arabic Tweets-Based Sentiment Analysis to Investigate the Impact of COVID-19 in KSA: A Deep Learning Approach. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 7, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc7010016

Althagafi, A., Althobaiti, G., Alhakami, H., and Alsubait, T. (2021). Arabic Tweets Sentiment Analysis About Online Learning During CovID-19 in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 12, 234147349. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2021.0120373

Aung, K. Z., and Myo, N. N. (2018). Lexicon Based Sentiment Analysis of Open-Ended Students’ Feedback. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, 8, 1–6.

Frank-Witt, P. (2020). Intentionality in art: Empirical Exposure. Journal of Visual Art Practice, 19, 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702029.2020.1752514

Igdalova, A., and Chamberlain, R. (2023). Slow looking at still art: The Effect of Manipulating Audio Context and Image Category on Mood and Engagement During an Online Slow Looking Exercise. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 19(3), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000546

Kastrati, Z., Arifaj, B., Lubishtani, A., Gashi, F., and Nishliu, E. (2020). Aspect-Based Opinion Mining of Students’ Reviews on Online Courses. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Computing and Artificial Intelligence ( 510–514). https://doi.org/10.1145/3404555.3404633

Khan, L. U., Yaqoob, I., Tran, N. H., Kazmi, S. M. A., Dang, T. N., and Hong, C. S. (2020). Edge-Computing-Enabled Smart Cities: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 7, 10200–10232. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2020.2987070

Nguyen, A., Nguyen, V. D., Nguyen, P. X., Truong, T. T., and Nguyen, N. L. T. (2018). UIT-VSFC: Vietnamese Students’ Feedback Corpus for Sentiment Analysis. In 2018 10th International Conference on Knowledge and Systems Engineering (KSE) ( 19–24). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/KSE.2018.8573337

Oriol, X., Amutio, A., Mendoza, M., Da Costa, S., and Miranda, R. (2016). Emotional Creativity as Predictor of Intrinsic Motivation and Academic Engagement in University Students: The Mediating Role of Positive Emotions. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01243

Ortega, M. P., Mendoza, L. B., Hormaza, J. M., and Soto, S. V. (2020). Accuracy Measures of Sentiment Analysis Algorithms for Spanish Corpus Generated in Peer Assessment. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Engineering and MIS ( 1–7). https://doi.org/10.1145/3410352.3410838

Soroa, G., Gorostiaga, A., Aritzeta, A., and Balluerka, N. (2015). A Shortened Spanish Version of the Emotional Creativity Inventory (ECI-S). Creativity Research Journal, 27, 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2015.1030313

Spatiotis, N., Perikos, I., Mporas, I., and Paraskevas, M. (2018). Evaluation of an Educational Training Platform Using Text Mining. In Proceedings of the 10th Hellenic Conference on Artificial Intelligence (1–5). https://doi.org/10.1145/3200947.3201049

Terkik, A., Prud’hommeaux, E., Alm, C. O., Homan, C., and Franklin, S. (2016). Analyzing Gender Bias in Student Evaluations. In Proceedings of COLING 2016: 26th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (868–876).

Tewari, A., Saroj, A. S., and Barman, A. G. (2015). E-learning Recommender System for Teachers Using Opinion Mining. In Information Science and Applications (pp. 1021–1029). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-46578-3_122

Trnka, R., Zahradnik, M., and Kuška, M. (2016). Emotional Creativity and Real-life Involvement in Different Types of Creative Leisure Activities. Creativity Research Journal, 28(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2016.1195653

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.