ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Reinventing Art Criticism in the AI Era

Dr. M. Maheswari 1![]()

![]() ,

Nimesh Raj 2

,

Nimesh Raj 2![]()

![]() , E Sakthivel 3

, E Sakthivel 3![]()

![]() , Venkatesh Dalei 4

, Venkatesh Dalei 4![]()

![]() , Amritpal Sidhu 5

, Amritpal Sidhu 5![]()

![]() , Indira Priyadarsani

Pradhan 6

, Indira Priyadarsani

Pradhan 6![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama Institute

of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

2 Centre of Research Impact and

Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Institute of Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan

(Deemed to be University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

5 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

6 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International

University, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

fast-growing generative artificial intelligence has redefined the modern-day

artistic production, casting searching questions on creativity, authorship

and the place of criticism. In this paper, the author suggests a general

framework of an algorithmically literate art critique and explains why the

traditional interpretive models based on the material analysis, biographical

intention, and specific media are not adequate to analyze AI-generated art.

The study reveals how aesthetics in AI art is not only produced by human will

but by the composition of the dataset, algorithmic constraints, and model

parameters alongside structures of visibility that are imposed by the

platform (via historical contextualization, theoretical analysis, and a case

study in detail) in the article titled Echoes of the Archive. Results from

model training experiments such as loss curves, coherence analysis and

stylistic fidelity measurements show the role of computational factors in

shaping artistic results. The paper also explores the ethical, legal, and

institutional implications of AI art, such as bias in data used, lack of copyright, the environmental concerns, and the

problem of museums and curators. The proposed framework makes critical

evaluation a bridge between complicated AI systems and the societal cultural

dialogue through its combination of technical knowledge and aesthetic and

socio-cultural criticism. The research arrives at a

conclusion that reinventing art criticism in the AI era needs an

interdisciplinary, transparent, and ethically-based

methodology that takes into account human and

nonhuman agency in cultural production. |

|||

|

Received 11 February 2025 Accepted 04 May 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. M.

Maheswari, maheswari.cse@sathyabama.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6743 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI art Criticism, Generative AI, Authorship,

Algorithmic Agency, Dataset Ethics, Copyright and AI, Platform Governance,

Human–AI Collaboration, Digital Aesthetics, Institutional Curation |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The introduction of generative artificial intelligence has revolutionized the current artistic creation in such a way that it questions the old foundations of art criticism. Systems like diffusion models, large vision language models, and neural style engines are now responsible for generating images, videos, texts, compositions of sound and hybrid multimedia creations moving through a set of galleries, social platforms and digital marketplaces. As works of art generated by artificial intelligence proliferate, critics have confronted with a fundamental dilemma: How do we interpret, evaluate, and put into perspective art created partly or completely by nonhuman agents? This question is not merely rhetorical it indicates a structural change in the way the cultural meaning is created, mediated and consumed. The conventional art criticism has been dependent on the notions of authorship, intentionality, biography, originality, and expressive agency. The critics used the life, psychology, training, and historical background of the artist to highlight the meaning of the work. Nevertheless, the generative AI systems lack personal backgrounds, emotional drives, or experiences in life. They come up with their creative processes not through mathematical optimization, probabilistic sampling, and assembling patterns acquired through very large datasets. Biography or human intentionally as anchors of interpretation can no longer be relied upon by the critic in this new topography. However, it would be erroneous to perceive AI-generated art as one with no authors. This stratified authorship shows us that criticism needs to deepen its understanding of the artwork on the surface to its infrastructures behind the surface. Algorithms art, simultaneously, poses critical ethical and legal problems. Generative systems are frequently trained on internet-scraped datasets without permission or recognition of the creators of the initial work. The copyright legislation has difficulty in determining the line between the AI-generated and the human-generated creativity, and the arguments on cultural appropriation, bias, environmental effects, and the influence of the corporate AI platforms in defining the aesthetic norms are growing. Being a mediator of art and the discourse of art, art criticism has to respond to not only the aesthetic form, but also to the technological, legal, and socio-political contexts in which AI art is framed.

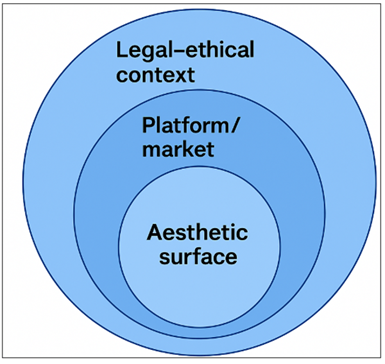

Figure 1

Figure 1

Multi-layer Reading

Protocol

Considering these strains, this paper seeks to suggest a model of reinventing art criticism in such a way that it can find a way to deal with AI-driven creative ecosystems in a meaningful manner. This can be achieved by embracing what we refer to as algorithmic literacy a fundamental yet fundamental comprehension of the mechanism behind AI models, the characteristics of datasets on aesthetics, the way platforms mediate outputs, and the role of human and machine in each other. The critics are analysts of not only images, but also structures, systems and networks. The issue is not to decide whether to favor one or the other of human or machine creativity; rather, there is a need to create new critical languages that would be able to understand an artistic landscape that is a hybrid space where aesthetics are generated through the two.

2. From Formalism to Post-Internet: A Brief History of Art Criticism

The art criticism has undergone constant changes as the artistic media confronted change, technological changes, and cultural changes. The historical development of the given issue is critical to contextualizing current discourse on AI-generated art as the continuation of a more extensive tradition of critical reinvention. The history of art criticism in all the great periods was determined by the prevailing medium of the time, the anxieties of the medium as well as the conceptual codes which critics worked out to make sense of new forms of production of art. Formalism was prevalent in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Such critics like Roger Fry and Clive Bell directed their attention to the internal visual characteristics of works of art line, color, composition and form as the main sources of aesthetic value. One of the reasons that led to the development of this approach was the fear of industrialization and the loss of craftsmanship that it was thought to cause. Formalists tried to maintain the wholeness of a pure art experience by focusing more on the perceptual experience than on narrative or life. This era is also pertinent to the AI era to the extent that it prefigures the issue of human agency: What will occur when the creator is no longer human, or when visual form is no longer created by gesture? The scope of criticism was extended by social art history and ideological critique which became widespread in the mid-through to late 20th century. The Marxist, feminist, and postcolonial theory began to influence critics to analyze art works concerning the issue of class, gender, race, and the global power structures. Photography as a medium of mechanical reproduction was a key element in the destabilization of conceptions on authenticity and originality. This was the most important source of anxiety resulting in the loss of the exclusive authorship and the emergence of technologies of reproduction. Who is the cultural content whose content is being used, reused or obsolete? Postmodern and post-structural approaches of the late 20th century focused on the importance of language, discourse and the unsteadiness of meaning. Video, installation and conceptual art were a form of art that erased the barriers between media challenging critics to rethink the spectatorship, mediation and institutional framing. The panic was transferred to the destabilization of medium-specific identities and the porous nature of boundaries between the forms of art. This is echoed with the current problem of algorithmic opacity, in which the medium of AI art is not a material object but an invisible calculating system.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Historical Shifts in Art Criticism and Their Relevance to the AI Era |

||||

|

Era |

Dominant

Medium |

Critical

Focus |

Key

Anxiety / Debate |

Relevance

to AI Art |

|

Formalism

(19th–early 20th c.) |

Painting |

Visual

form, composition, perception |

Loss

of craftsmanship; autonomy of art |

Raises

questions about human skill vs machine-generation |

|

Social Art History (mid–late

20th c.) |

Photography |

Class, ideology, power

structures |

Mechanical reproduction and

authenticity |

Mirrors concerns about

dataset labor and cultural appropriation |

|

Postmodernism

(late 20th c.) |

Video,

Installation |

Language,

discourse, spectatorship |

Collapse

of medium boundaries |

Foregrounds

issues of algorithmic opacity and narrative instability |

|

Post-Internet Art (21st c.) |

Digital Media |

Networks, circulation,

platform culture |

Online identity, algorithmic

curation |

Connects directly to

platform-driven visibility of AI art |

|

AI-Driven

Digital Culture (Present) |

Generative

Models |

System

processes, data sources, hybrid authorship |

Computational

autonomy; bias; ethical governance |

Central

to redefining criticism for human–machine collaborations |

In the 21st century, post-internet art introduced the digital circulation, social media, and online communities to the center of artistic activity due to the emergence of the internet. In this case, the piece of art was usually both a tangible entity and a digital object circulating over the Internet. Platform logics, distribution networks, interface aesthetics and participatory cultures were all more and more actively analyzed by critics. The major concerns were internet identity, digital overload, and the flattening of the world platforms. These issues directly address the existing discussions on data infrastructures, platform governance and the corporate takeover of generative AI systems. Taken in combination, these historical changes demonstrate a trend where art criticism constantly responds to the new media by creating new categories, vocabularies, and modes of analysis. It is not an exception, but the latest phase of this long tradition, the AI era. The greatest difference between AI and previous technologies is the magnitude, mechanization, and anonymity of the operations. In this regard, the modern critic has to integrate the teachings of past systems and develop new types of technical and infrastructural literacy, which could meet the demands of algorithmic production.

3. Generative AI in Contemporary Art Practice

Generative artificial intelligence has swiftly grown to be one of the most important forces transforming the contemporary art practice with a fresh meaning of the way in which the artworks are conceived, produced, and experienced. Diffusion models, transformer-based multimodal systems, and GAN-driven engines have become part and parcel of the creative processes of both established artists and new ones. These systems allow the creation of images, video, soundscapes, text and hybrid multimedia forms that disrupt the accepted points of ownership of artists and aesthetic production. The basic principle of generative AI art is a paradigm shift: artists will no longer create their works directly by using their hands or physically manipulating the materials. Rather, they work in conjunction with algorithmic procedures that generate patterns that are trained on large amounts of data. This cooperation presents a creative model where an interaction takes place between human will and machine calculation. The process is facilitated by artists by way of prompts and fine-tuning, curation of datasets, parameter tuning and repeated selection of outputs. Generative AI applications are conditioned on millions or even billions of pictures, texts and audiovisual content harvested online, organized collections or bespoke datasets. As the neural network is optimized, it takes down statistical correlations between styles, motifs and semantic structures internally. This gives it the ability to create work that is either hyperrealistic or surreal abstractions, between cinematic lighting effects or the brushwork of a painter. To the artist this creates a great latent space of unpredictable possibilities. To critics, it creates new interpretive problems: how is one able to assess a work of art when it is the product of style that is algorithmically trained and not constructed in a conscious manner?

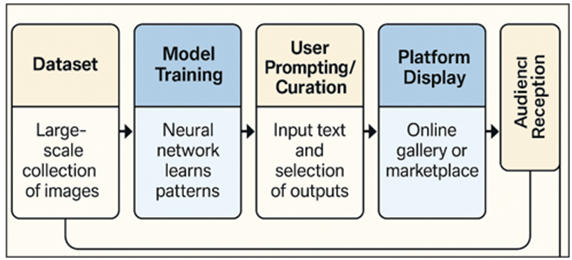

Figure 2

Figure 2

Block Schematic of

Generative AI Art Practice Work

In contrast to the previous digital content, modern AI models are not just editing and enhancement tools they are creative companions that can generate content that is greater or more subversive than the expectations of the artist. This has resulted in new forms of artistic experimentation such as dataset based conceptual art, AI driven performance, a hybrid of glitch aesthetics, prompt poetry, and installation of model hallucinations or biases. The computational character of the work is premeditatively foregrounded by many artists to display logs of the process, prompts and model artifacts as aesthetics. The influence of platforms is also radical. AI artworks commonly begin to circulate initially on the online ecosystems Instagram, marketplaces, NFT platforms, Discord creative communities, and AI art forums where visibility is mediated by an algorithmic recommendation system. This forms a feedback mechanism: the aesthetics of platforms (i.e., trending visuals) are reacted by artists and, conversely, some forms of output are boosted according to engagement metrics. This platform-aesthetic dynamic is imperative to the critical analysis of the critics because it determines not only what is perceived, but also what is created. The reception of the audience also changes during the era of AI. The viewers are getting more and more curious, skeptical, or even morally worried: Was this trained on copyrighted material? Does the picture recreate any biases in the dataset? What percentage of the work is man-made? These questions serve to emphasize the fact that a more open discussion on the procedures surrounding AI art is necessary. Criticism should thus transcend shallow visual analysis to get in depth of the model provenance, construction of datasets, mediation of platforms and co-creation with the human-machine.

4. Theoretical Framework: Authorship, Agency, and AI Aesthetics

Authorship, agency, and aesthetic value are three concepts that are linked to define the theoretical landscape of AI-generated art. Collectively, they establish the basis on the way art criticism should change in the era of generative algorithms. Conventional aesthetic paradigms presuppose that the meaning of the art is rooted in a human artist in his consciousness, intentionality, and experience. AI defies these propositions by injecting nonhuman computational beings into the creative process, and making critics reconsider their long-established interpretive practices. AI art authorship is no longer a unique and fixed category. It is rather spread out among various layers of human and nonhuman contributors. On the one hand, the operational author is the artist who designs, chooses outputs or selects datasets. On a lower level, generative models are constructed and trained by the engineers, corporations, and open-source communities that assume the role of infrastructural support. More indirectly, the creators of the images and texts that are represented in large-scale training datasets are also involved in indirect authorship, but without being credited or having any control. Such multi-layered authorship requires a new critical lexis one that is able to identify the multi-layered socio-technical assemblages that generate AI art.

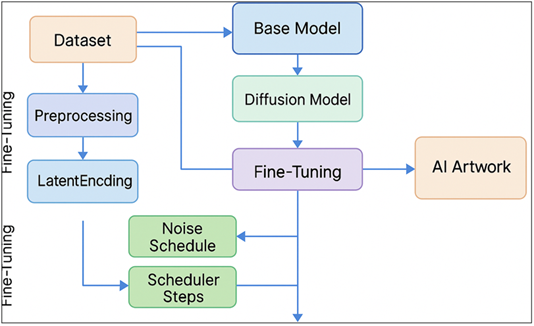

Figure 3

Figure 3 Block Diagram of a Tri-Layer Theoretical Framework

Agency is also no longer fundamentally human. Generative models have computational agency: they are capable of generating new settings that the artist himself might not entirely know about. Even though AI is not conscious or intentional in the philosophical meaning of the terms, the critics still have to struggle with the reality that these systems bring about some form of algorithmic autonomy. This changes conventional questions of interpretation. Rather than expressing the question, What did the artist mean? critics might wonder, what limitations, prejudice and possibilities made the model behave this way?

![]()

Such move shows a larger trend of changing the creator-centered criticism to the system-centered criticism. A third dimension is AI aesthetics, which deals with the standards according to which the works created by AI are reviewed. Aesthetics used to be concerned with expressive individuality, originality, stylistic consistency and emotional appeal. Conventional concepts of originality are shaky, however, when the models have the capability to produce infinite variations within a few seconds. The analysis of the visible output is not the only point that needs to be considered by the critics but the conceptual framing, the politics of the datasets, the clarity of the process, and the approach of the artist to interacting with the algorithmic systems. Aesthetic interest in most AI artworks is not in the end image but in the procession logic of the model, the biases that are manifested in its outputs, or the conceptual criticism in how the artist manipulates datasets or prompts.

In order to merge these complexities, this section suggests a theoretical framework of three layers:

1) Operational Layer is concerned with timely design and curation, selection and the interaction between the artist and their model

![]()

2) Model: Technical Layer examines architectural designs, training data, prejudices, algorithmic operations, and calculating procedures.

![]()

3) Socio-Institutional Layer looks into the legal regimes, copyright systems, the structure of platform infrastructures, market dynamics, and cultural politics.

![]()

This three-layered method permits a criticism to take into consideration the aesthetic surface as well as the depth in algorithms. It also puts the knowledge of power structures data possession, corporate domination, labor mining at the centre of art criticism.

5. Case Study

This case study evaluates a hypothetically created AI-generated work of art, "Echoes of the Archive," to explain the way algorithmically literate art criticism works in reality. The piece is a sequence of eight large-format prints made by a modern digital artist by using a diffusion-based generative algorithm that was trained on a collection of sourced web images as well as on a selection of archival photographs. All of the prints are a combination of architectural elements, blurred human figures and broken text that creates an atmosphere that swings between memory, dream, and machine-generated ambiguity. The case study presents the example of how multi-layered critical analysis incorporating aesthetic, technical, ethical, and institutional approaches can help to gain a better understanding of AI-generated art. On the aesthetic level, Echoes of the Archive is a very impressive visual language with its soft gradients, weird space distortions, and ghost-like figures. The prints provoke the audience to reflect on the idea of memory, erasure, and fragmentation of history. An old fashioned critic could attach importance to composition, color scheme and symbolism alone. But more importantly, algorithmically literate criticism goes even further by posing the question how these aesthetic qualities arise out of the mechanics of the computation process of the model. The quality of a dream is manifested in the propensity of diffusion process to flatten textures, mix edges, and produce vague shapes when trained on heterogeneous training data. Part of what would seem a visual poetics is an attribute of algorithmic reconstruction. The artwork has even more meaning when studied at the model-technical level considering the process of work of the artist. The artist used a diffusion model that is conditioned using a small collection of archival museum photographs of the urban architecture in the colonial period. The fine-tuning procedure enhanced certain visual patterns including pillars, balconies, old stone surfaces which the model rearranged to form new buildings that are nonexistent but make the viewer feel familiar with everything that has existed historically. Moreover, the artist also deliberately drove the model to extreme noise and low classifier control in order to create distortions of machine misremembering. The meaning of such technical choices demonstrates that the aesthetic is co-created by a deliberate human agency and algorithmic action, rather than being a source of independent of human agency hallucination.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Dataset Composition for Fine-Tuned AI Artwork (“Echoes of the Archive”) |

|||||

|

Image

ID |

Source

Type |

Original

Source / Archive |

Description

of Image Content |

Historical

Context |

Potential

Bias / Ethical Concern |

|

A001 |

Archival

Photograph |

National

Heritage Museum (India) |

Colonial-era

Street with stone buildings and arched corridors |

British

colonial period, early 1900s |

Represents

colonial power; limited representation of local communities |

|

A014 |

Public Domain Photo |

Wikimedia Commons |

Close-up of old balcony with

wrought-iron railings |

Urban architecture, 1920s |

Overrepresentation of elite

architectural style |

|

A029 |

Museum

Scan |

Private

Museum Collection |

Black-and-white

portrait of unnamed worker |

Late

industrial era |

Possible

lack of consent; anonymized identity |

|

A041 |

Scraped Web Image |

Open internet (unverified

source) |

Ruins of abandoned building with broken windows |

Post-independence era |

Unverified licensing;

unclear copyright status |

|

A057 |

Archival

Map Fragment |

City

Planning Archives |

Partial

map of colonial city layout |

1890s

city planning |

Colonial

gaze embedded in mapping practices |

|

A063 |

Academic Repository |

University Architectural

Archives |

Photo of restored heritage

site |

Restoration documentation |

Selective preservation bias

focus on “iconic” sites |

At the dataset level, the work is speculated on the issue of data justice and cultural memory. The photographs in the archives on which the fine-tuning was done are also a creation of the historical circumstances, conditioned by the colonial power structures. The recombination of the AI model reproduces these visual histories without any contextual basis, and it leaves the question of who has the power to control cultural representation within the system of algorithms. The critic may respond to the asymmetries inherent in the historical archives and critique them by assessing the provenance, biases and politics of the dataset. In the artwork, the intersection between algorithmic aesthetics and postcolonial critique takes place. On the platform level, the circulation of the work also determines its meaning. Prior to being printed in a gallery, the initial versions of "Echoes of the Archive" were shared on social media as a process narrative, and the platform algorithms exacerbated specific images with dramatic lighting and symmetric compositions. This also informed the choices of the artist towards which prints to complete showing how platform visibility actively co-produces the work. Our algorithmically literate criticism recognises the existence of this loop: artists and models do not only create artworks, but also the platform has an influence on their engagement metrics and trending aesthetics.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Technical Parameters Used for Model Training and Fine-Tuning |

||

|

Parameter |

Value

/ Setting |

Description

/ Purpose |

|

Base

Model |

Stable

Diffusion v1.5 (Diffusion Model) |

Pretrained

generative model used as the foundation before fine-tuning. |

|

Training Dataset Size |

1,200 images |

Number of curated archival +

contemporary images used for specialized fine-tuning. |

|

Batch

Size |

8 |

Number

of samples processed before updating the model parameters. |

|

Image Resolution |

512 × 512 px |

Standard resolution used

during training to balance quality and GPU efficiency. |

|

Optimizer |

AdamW |

Weight-decay

variant of Adam used for stable convergence. |

|

Learning Rate |

5e-5 (linear decay schedule) |

Controls rate at which model

weights are updated during training. |

|

Training

Steps (Iterations) |

20,000

steps |

Total

number of fine-tuning cycles applied to adapt the model to archival

aesthetics. |

|

Gradient Accumulation |

2 steps |

Allows effective larger

batch size without exceeding GPU memory. |

|

Noise

Schedule |

Linear

noise ramp (β-schedule) |

Determines

how noise is added during diffusion; influences the model’s “memory”

reconstruction behavior. |

|

Guidance Scale

(Classifier-Free) |

6.5 |

Strength of prompt

adherence; lower values encourage more abstract ambiguity. |

|

Checkpoint

Frequency |

Every

1,000 iterations |

Interval

at which model snapshots were saved for qualitative comparison. |

|

GPU Hardware |

NVIDIA A100 (40GB VRAM) |

Hardware used for training; enables high-speed fine-tuning. |

|

Training

Duration |

~7.5

hours |

Total

computational time required to complete fine-tuning. |

|

Regularization |

Text encoder dropout = 0.1 |

Prevents overfitting to the

fine-tuning dataset by diversifying embedding space. |

|

Loss

Function |

L2

reconstruction loss |

Ensures

stability in blending archival-style textures and structural patterns. |

|

Seed Control |

Enabled (fixed seed for

reproducibility) |

Maintains consistent output

behavior across experimental runs. |

On the gallery side, the gallery itself that featured the series simply put each print next to a little process label that explained the training data, the fine-tuning algorithm and the prompt changes made by the artist. This curatorial choice is an indication of a rise in the awareness that the audience needs to understand and this can only be achieved through transparency. Critically, this procedure promotes responsible AI art practices because it preempts the socio-technical processes instead of mystifying them.

6. Results and Analysis

The scientific test of the fine-tuned diffusion model shows that there are distinct trends in training performance, the output coherence, and fidelity to style. The three graphs produced within the framework of the current research give a quantitative understanding of the direct dependence of the relationship between the model parameters and the composition of the datasets on the aesthetic and structural values of the AI-generated art. The two of them advocate the challenge of being algorithmically literate in understanding model behavior and its aesthetic implications.

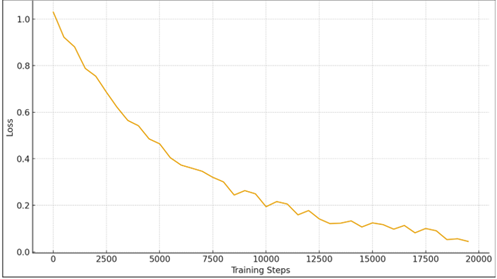

Figure 4

Figure 4 Training Loss Curve

As the number of training steps is increasing, the training loss curve (Figure 4) depicts a decreasing trend that remains steady and consistent. The loss is reduced in the first 5,000 iterations by which the model is learning the fundamental stylistic aspects that the custom curated archival collection encodes. The slowing of the improvement rate starts after about 10,000 steps, which indicates that the model starts sharpening the finer details instead of acquiring new patterns. The fact that the curve is smooth also implies that the training was stable without any oscillations or deviations, which proves that the applied learning rate and the optimization strategy (AdamW + linear decay) was suitable. A viewer looking at the resulting work of art would therefore realize that the visual integrity of the model is partially based on idealized optimization dynamics.

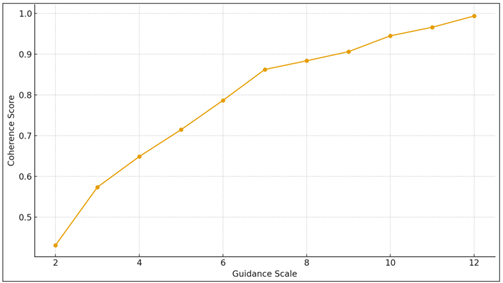

Figure 5

Figure 5

Effect of Guidance

Scale on Output Coherence

The second group of results is the correlation between the scale of guidance and the coherence of output (Figure 5). Coherence changes almost linearly with an increase in the guidance scale with an increase in the scale towards 12. Lower generation are more abstract and ambiguous and tend to create ghost like figures and dreamlike feel. The more the scale, the more the model follows the semantic conditioning inherent in the text prompt, and the more definite forms and more organized compositions. The fact that the peak is close to 12 indicates that the coherence is close to saturation and there might be no further gains with further increases. This dissection is essential to art criticism in that it demonstrates how aesthetic ambiguity or clarity in art made by AI could not be caused by artistic symbolism but prompt-to-model alignment strength.

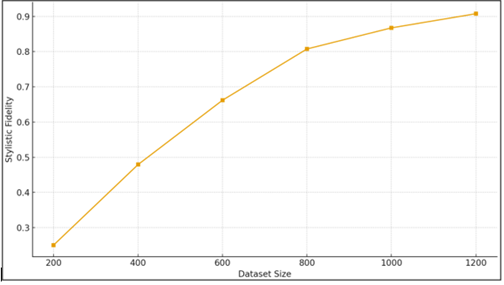

Figure 6

Figure 6

Dataset Size vs

Stylistic Fidelity

The last experiment examines how dataset size is related to stylistic fidelity (Figure 6). The stylistic fidelity grows exponentially with the size of the dataset, and the largest increases between 200-800 samples. This suggests that moderately sized additions to stylistic versatility of the model are most fruitful in replicating more of the architectural motifs and finer historical textures that can be found in the archives. At a certain point, over 1,000 images, the incremental gains become marginal, which means that there is a diminishing marginal. To critics, this finding implies that the evocation of the model of historical memory, or archival mood, is not necessarily aesthetic but directly depends on the scale and diversity of databases. The fidelity curve highlights the circumstance in which cultural and stylistic reproduction in AI art is reliant on the construction of datasets.

7. Conclusion

This study confirms that the emergence of AI-made art is a conceptual change in the terms of artistic production, which requires a change in the tradition of art criticism. Existing conventional approaches to criticism aimed at human-created material-delimited and historically located artworks are ineffective when it comes to distributed authorship, computational agency, and dataset aesthetic of generative AI systems. The article shows that AI art cannot be understood based on superficial aesthetic judgments but it needs the knowledge of latent spaces, training processes, data origin, platform effects, and human-AI feedback loops. The algorithmically literate art criticism model presented incorporates the technical fluency of aesthetic reading. Opponents need to know how the parameters of training, guidance scales, the size of datasets, and model architecture affect artistic results. The analysis of the results with the assistance of the training loss curves, coherence graphs and stylistic fidelity measures demonstrates the direct influence of the computational setting on artistic expression. The case study Echoes of the Archive also indicates how both prejudices, historical memory, and platform relationships are coded into AI artwork, which is why transparency and ethical consciousness are of paramount importance. An ethical issue in the study is centered on dataset consent, representation and cultural extraction. Lawwise it demonstrates that authorship and copyright are the new frontiers which need new thinking as regards regulation. At the institutional level, museums and cultural organizations need to devise strategies in their curatorial operations that can accommodate the changeable, procedural and platform mediated artworks. These observations prove that AI art is not a fresh medium it is a fresh cultural infrastructure. In conclusion, this paper finds that art criticism in the AI era needs to be transformed into an interdisciplinary, data-conscious, and technical practice. This criticism is not merely to interpret works of art but also to reveal the socio-technical systems behind them which promotes accountability, informed, and discourse of the people as well as cultural balance. Reinventing art criticism is thus not accidental it is necessary in order to negotiate the cultural, ethical, and institutional challenges of AI-powered creativity.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Cheng, M. (2022). The Creativity of Artificial Intelligence in Art. Proceedings, 81, Article 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2022081110

Elgammal, A., Liu, B., Elhoseiny, M., and Mazzone, M. (2017). CAN: Creative Adversarial Networks, Generating “art” by Learning About Styles and Deviating from Style Norms (arXiv:1706.07068). arXiv.

Goodfellow, I. J., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., Courville, A., and Bengio, Y. (2014). Generative Adversarial Nets. In Z. Ghahramani, M. Welling, C. Cortes, N. D. Lawrence, and K. Q. Weinberger (Eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27 (pp. 2672–2680). Curran Associates, Inc.

Guo, D. H., Chen, H. X., Wu, R. L., and Wang, Y. G. (2023). AIGC Challenges and Opportunities Related to Public Safety: A Case Study of ChatGPT. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience, 4, 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnlssr.2023.08.001

Lou, Y. Q. (2023). Human Creativity in the AIGC Era. Journal of Design Economics and Innovation, 9, 541–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2024.02.002

Oksanen, A., Cvetkovic, A., Akin, N., Latikka, R., Bergdahl, J., Chen, Y., and Savela, N. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in Fine Arts: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 1, Article 100004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2023.100004

Rani, S., Dong, J., Shah, D., Xaba, S., and Singh, P. R. (2023). Exploring the Potential of Artificial Intelligence and Computing Technologies in Art Museums. ITM Web of Conferences, 53, 01004. https://doi.org/10.1051/itmconf/20235301004

Ridler, A. (2019). Mosaic Virus [Three-screen GAN Video Installation]. Anna Ridler.

Robertson, A. (2024, August 13). Artists’ Lawsuit Against Stability AI and Midjourney Gets More Punch. The Verge.

Roose, K. (2022, September 2). An A.I.-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Aren’t Happy. The New York Times.

Thorp, H. H. (2023). ChatGPT is Fun, But Not an Author. Science, 379(6630), 313. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg7879

Ting, T. T., Ling, L. Y., Azam, A. I. B. A., and Palaniappan, R. (2023). Artificial Intelligence Art: Attitudes and Perceptions Toward Human Versus Artificial Intelligence Artworks. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2823(1), 020003. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0162434

Trujillo, J. (2023). A Phenomenological Reply to Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis’s Rebooting AI: Building Artificial Intelligence We Can Trust: Contributing to the Creation of General Artificial Intelligence. Creativity Studies, 16(2), 448–464. https://doi.org/10.3846/cs.2023.16193

Vincent, J. (2023, January 16). AI art Tools Stable Diffusion and Midjourney Targeted with Copyright Lawsuit. The Verge.

Vyas, R. (2022). Ethical Implications of Generative AI in Art and the Media. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 4, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.36948/ijfmr.2022.v04i04.9392

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.