ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Algorithmic Ethics in AI-Created Artworks

Dr. Rajita Dixit 1![]() , Dr. Jayashree Patil 1

, Dr. Jayashree Patil 1![]() , Dr. Ketaki Anay

Pujari 3

, Dr. Ketaki Anay

Pujari 3![]() , Dr. Devendra

Puntambekar 4

, Dr. Devendra

Puntambekar 4![]() , Yuvraj Parmar 5

, Yuvraj Parmar 5![]()

![]() , Gurpreet Kaur 6

, Gurpreet Kaur 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Centre for Distance and Online Education, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed

to be University Pune, India

2 Centre for Distance and Online

Education, Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be University) Pune, India

3 Director (E-Learning and Skill

Development), Centre for Distance and Online Education, Bharati Vidyapeeth

Deemed to be University Pune, India

4 Chitkara Centre for Research and

Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

5 Associate Professor, School of

Business Management, Noida International University, Greater Noida, Uttar

Pradesh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

information presented in this paper explores the changing ethical issues that

come with AI-generated artworks, and how algorithms, datasets, and the

behavior of model-layers, cultural sensitivity, and the governance structures

influence artistic results. The research evaluates various aspects of ethical

risk, such as the spread of bias, stylistic theft and misrepresentation of

culture, as well as manipulation of identity. Based on a multi-layered

analytical framework upheld by graphs, tables, and case studies, the study

points out that the main ethical vulnerabilities are due to uneven datasets,

obscure semantic-layer reasoning, and inadequate protection of culturally

sensitive information. To illustrate how the failures of ethics are put into

practice, the paper introduces five real-world case studies that include

unauthorized style mimicry, distortion of Indigenous symbols, the bias of a

demographic portrait, exploitation of community heritage datasets, and

manipulation of identity by a deepfake to prove how they may fail in

practice. The results show that governance interventions, including

consent-driven datasets, fairness auditing, cultural-protection mechanisms,

and identity safeguards, can greatly mitigate the harmful output, which is

achieved through their regular use. The paper ends with an overview of the

future directions that focus on contextual cultural intelligence, adaptive

governance, semantic interpretability and community

oriented data rights. The general aim is to influence the creation of

morally accountable generative AI applications, which are cognizant of

creative authority, culture, and social trust. |

|||

|

Received 12 February 2025 Accepted 06 May 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Rajita Dixit, rydixit@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6740 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Algorithmic Ethics, AI-Generated Art, Cultural

Representation, Bias Mitigation, Style Mimicry, Dataset Governance, Deepfakes |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The advent of artificial intelligence as an innovative partner has redefined the bases of creative expression and authorship and artistic production. Compared to the older types of computational aids to human creativity, newer generative models like diffusion models, GANs, transformers, and hybrid neuro-symbolic systems have the ability to autonomously generate artworks that are stylistically and coherent, as well as original and have aesthetic intent. This has introduced artists, designers, educators and cultural institutions with unparalleled creative possibilities Chan and Hu (2023). However, it also has brought to light the new range of ethical, philosophical, and other socio-technical problems that are summed up as algorithmic ethics in the works of AI. With the ever-increasing use of AI-driven art in the entertainment industry, advertising, design, and fine arts, its ethical consequences are requiring systematic investigation Hurlburt (2023). The key issue in the focus of this discussion is the question of how algorithms influence decisions that drive creative production. There is a great deal of stylistic work, cultural motifs and personal photographs many of which were not obtained with explicit permission downloaded onto training datasets which frequently consist of millions of internet-scraped images. This poses some of the basic questions of representation, ownership, privacy, and cultural appropriation. It is also important that the algorithmic biases are entrenched in these datasets Morley et al. (2021). By favoring production that reinforces dominant cultures, mainstream aesthetic values, or visual norms historically predominant, the risks of generative models allowing people to propagate the structural inequalities are high, as well as marginalizing the artistic traditions underrepresented in history. These issues dispute the inclusiveness and reasonableness of AI-driven creativity Acion et al. (2023).

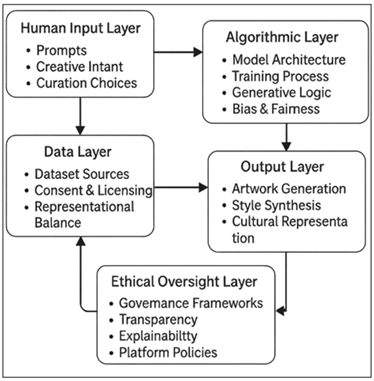

Figure 1

Figure 1 Ethical Layers in AI-Created Artworks

More so, the ontology of authorship is highly contentious during the era of autonomous generation. The AIs lack consciousness, emotional, and intentionality in the human understanding, but they create works that are as beautiful as the artistic genius of human beings. Authorship issuesare controversies on whether the developer, dataset contributors, end-user, or the model itself should be credited with any credit Voss et al. (2023). Such complications support the necessity to differentiate between mechanical, conceptual, and cultural authorship (data-driven influence involving people). Ethical theories will need to deal with the distribution and valuation of creative labor in a world where the line between human and machine production is permeated as in Figure 1. Such systems usually have no transparent data concerning their datasets, training processes, filtering layers, and moral principles. In the absence of strong mechanisms of governance, AI-generated art may be exploited to facilitate deepfakes, misinformation, and iconographic distortion, on the other hand, could be used to exploit the repurposing of cultural heritage. It has also been found that the necessity of effective ethical standards, accountability frameworks, and open platform policies has become crucial Baldassarre et al. (2023). In this paper, the ethical environment of the AI-generated works is discussed in terms of the philosophical context, technical processes, data, cultural safety, author issues, and regulations of the generative systems. The work will aim to enhance the responsible innovation of creative AI ecosystems by developing a multi-layer ethical model conceptualization Lee et al. (2024). The section ends with a suggestion of a synthesized perspective: the notion that algorithmic ethics is not only a technical limitation but an imperative that is both cultural and philosophical and a policy-based fact, which needs to be co-evolved with conceptual AI.

2. Conceptual Foundations of Algorithmic Ethics in Creative Systems

The ethical environment of AI-created works is based on a number of conceptual bases that shape the conceptualization of creativity, agency, responsibility, and cultural value in the context of involving machines in the artistic production process. Conventional concepts of creativity locate a human artist as a prime actor, who has will, emotion and subjective explanation Lee et al. (2024). But with the advent of machine-generated works, this anthropocentric definition is put into question. Newer generative models are created using outputs through the synthesis of outputs guided by statistical patterns, latent representations, and probabilistic creativity, raising some new questions: Can algorithms be creative? Who is ethically responsible of their output? The central feature of algorithmic ethics is the difference between algorithmic agency and a human intention.

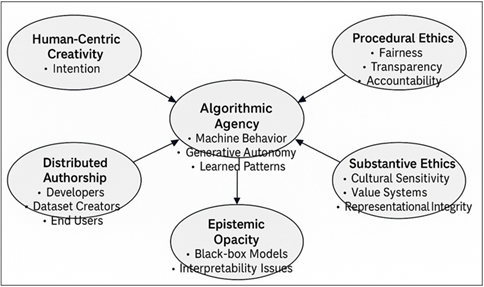

Figure 2

Figure 2 Conceptual Foundations of Algorithmic Ethics in

Creative AI

AI systems are not conscious or motivated, they are executed according to the programmed goals, training inputs, and learned representations. Nevertheless their products are frequently new and complicated to the extent of human artistic intuition. This brings an intellectual conflict between mechanical production and the seeming invention Thambawita et al. (2021). Ethical paradigms should hence demystify that although AI will be used as a means of action, it is also carrying out activities that will impact cultural meaning, aesthetic standards and social representation as an impact of creative agency as depicted in Figure 2. The other underlying idea is the philosophical argument in the area of AI between procedural and substantive ethics. Procedural ethics deals with the justice and transparency and technical responsibility of algorithms. Substantive ethics on the other hand dwell upon the quality of output and cultural implication of the outputs themselves, which are the objects of interest Sandiumenge (2023). The field of AI-generated artworks has its own set of procedural ethics that include issues of consent to data usage, minimization of biases, or explainability, and substantive ethics that focuses on the cultural appropriation, representational dignity, and the moral message embedded in the generated artworks. The two dimensions are supposed to be incorporated to carry out a holistic appraisal of ethical Tang et al. (2023).

Algorithms ethics should be based on cultural conceptuality. Art is never developed or analyzed as a vacuum, but rather it is incorporated into social, historical, and cultural accounts. The technical correctness is not the ethical issue of the AI-made art pieces that mimic indigenous, religious, or culturally sensitive imagery. The principles of algorithmic ethics should thus be based on consideration of cultural sovereignty, care about marginalized communities, and sustainable creative custodianship.

3. AI Models, Datasets, and Generative Processes: Ethical Considerations

The ethical dilemmas of AI-generated artworks are deeply intertwined with the type of models that they are trained on, the data that they are trained on, and the generative processes by which work is generated Nah et al. (2023). Current generative AI is based upon large-scale machine learning models including diffusion models, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Vision Transformers, and multimodal encoder–decoder architectures. Millions or billions of images found on the Internet in public websites, digital repositories and creative archives are used to learn by these systems McCradden et al. (2020). These datasets directly influence their synthesis of new artistic material and therefore, data provenance, licensing guidelines, representational fairness, and cultural sensitivity are at the forefront of ethical issues.

3.1. Data Collection

Data set legitimacy is one of the most essential problems. Most of the training data is automatically scraped by the web, usually without the permission of the original authors. Consequently, copyrighted art work, personal photographs, and culturally sensitive photographs are forcefully sucked into the latent space of the model. This poses a serious ethical dilemma in terms of consent, privacy, ownership and intellectual property as set out in Table 1. Artists can also have their styles replicated or imitated without rewards, and this brings about an issue of exploitation of creativity. The proper development of AI as an ethical field implies the documentation of datasets, the presence of the opt-out process, and the mechanism of the respectful representation of the rights of creators.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Dataset Attributes, Sources, and Ethical Compliance Metrics |

||||||||

|

Dataset

ID |

Dataset

Name |

Source

Type |

Licensing

Status |

Representation

Diversity Score (0–1) |

Contains

Sensitive Content? |

Cultural

Heritage Content? |

Risk

Level |

Notes

/ Ethical Actions Required |

|

DS-001 |

LAION-5B

Subset A Rhim et al. (2021) |

Web-scraped

image corpus |

Mixed

(some unverified) |

0.42 |

Yes

(faces, private photos) |

Minimal |

High |

Requires

filtering, consent verification, and removal of flagged images. |

|

DS-002 |

Public Domain Art Archive McKinley et al. (2024) |

Museums and heritage

repositories |

Public Domain (CC0) |

0.78 |

No |

Yes (historical artworks) |

Low |

Low-risk; still requires cultural

sensitivity tagging. |

|

DS-003 |

Contemporary

Artists’ Collection Murphy et al. (2021) |

Direct

submissions |

Explicit

Artist License |

0.65 |

No |

No |

Low |

Fully

compliant; add watermark-protective attribution metadata. |

Intimately connected with dataset legitimacy is the representational bias. Generative models replicate the biases of their inputs when the datasets they infer samples are disproportionately representative of Western aesthetics, or other dominant artistic traditions, or other demographic characteristics Zhong et al. (2023). Cultural erasure can be caused by underrepresentation of minority groups, non-Western art, or indigenous themes or the eroticization of feminist aesthetics. Besides, generative models have the unintended side of reinforcing stereotypes, as they can relate specific art styles to certain identities. Ethical AI art production should thus strive to provide balance to the datasets, cultural plurality and sensitivity to the art heritages.

3.2. Generative Process Dataset

Further ethical complexities are introduced by itself of the generative process. The processes are not entirely decipherable, so it is hard to diagnose why some of its outputs are similar to certain works or include some subtle signifiers of the style that seem derivative.

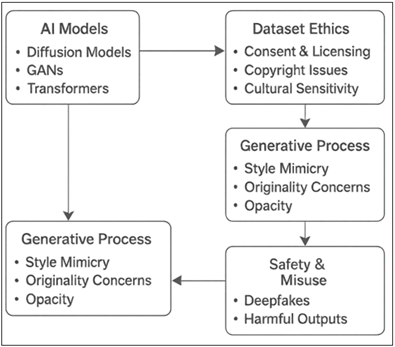

Figure 3

Figure 3 Block Schematic of Dataset Generative Process

The question of originality and art authenticity is brought up by this obscurity. Ethical judgments have to be carried out in terms of whether the artworks created are transformation, reproduction, or interpolation of the existing ones. The other important ethical point is associated with style mimicry. The signatures of current artists can be recreated using generative models, at times with almost perfect accuracy. Although this is technically wonderful, it brings about the issue of artistic plagiarism, creativity identity watering down as depicted in Figure 3 and the possibility of livelihood disruption. Ethical theories need to establish limits on stylized imitation, where AI technologies can serve instead of destroying human creative work. More so, content safety is necessary. The models are also capable of being abused to generate illusory images deepfakes, engineered identity images, disinformation images, or culturally offensive images. Unless supported with sturdy filtering, exposeability layers and safety measures, AI art devices may turn into misinformation sources or tools of cultural destruction. The carrying out responsibly of AI thus involves the use of guardrails, which include content moderation pipelines, explainable generation logs, and the deployment settings.

4. Case Studies in Algorithmic Ethics for AI Art

The case studies presented in the real life can provide a concrete view of the way ethical risks become a reality with generative AI systems. The five listed cases are some of the most popular and influential events in the ecosystem of AI-art. Every case brings out a unique ethical loseranging through unauthorized copying of style to deepfakes misuse and illustrates the applicability of responsible governance in practice. Tables are elaborated with each story in order to carry out organized analysis.

Case -A] Style Mimicry of Living Artists by

Unauthorised Style.

The initial one involves the generative AI tools that mimicked the unique style of visual artists without their consent. The models were discovered by artists to generate images almost indistinguishable with their signature techniques when using text-only prompts. This was because training sets contained copyrighted artworks that were scraped online with no permission as stated in Table 2. The AI thus learned style features on a baseline level and recreated them when required. It is not the reproduction that is relevant to the ethical question but the loss of the creative agency and means of livelihood. Mimicry of style dismays the distinction between influence and identity theft and leaves legal and moral issues of ownership of artistic style unanswered Montomoli et al. (2024). This case refers to the importance of dataset provenance, opt-out systems of styles and compensation systems to guarantee artistic rights.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Unauthorized Style Mimicry of Living Artists |

|

|

Dimension |

Details |

|

Case

Summary |

AI

tools reproduced unique artistic styles without consent. |

|

Primary Cause |

Web-scraped datasets

containing copyrighted works. |

|

Ethical

Issues |

Creative

identity theft, loss of livelihood, copyright ambiguity. |

|

Stakeholders |

Artists, platforms,

developers, users. |

|

Risk

Level |

High |

|

Recommended Actions |

Style-protection filters,

artist opt-out, dataset transparency. |

Case -B] Deception of Sacred and Indigenous Cultural

Symbols

The case shows that the creation of art by AI might misrepresent, devalue, or disrespect traditional cultural artifacts. Models trained on massive datasets tend to process culturally meaningful imageriesuch as Indigenous clothing or ceremonial equipment, or tribal patternslike as aesthetic codes. Lack of contextual insight can result in poor imagery or unacceptability. There was a backlash by the community when AI instruments produced stylized images of religious artifacts or symbols combined with other irrelevant objects Li et al. (2023). The indigenous people referred to such outputs as cultural appropriation or spiritual violation using digital means. This case highlights the necessity of culturally limited data sets, securing metadata, and community management framework which stipulates how available heritage imagery should be used.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Misrepresentation of Sacred and Indigenous Cultural Symbols |

|

|

Dimension |

Details |

|

Case

Summary |

AI

inaccurately reproduced sacred Indigenous symbols. |

|

Primary Cause |

Lack of cultural annotation,

insensitive dataset composition. |

|

Ethical

Issues |

Cultural

appropriation, symbolic distortion. |

|

Stakeholders |

Indigenous communities,

anthropologists, developers. |

|

Risk

Level |

Very

High |

|

Recommended Actions |

Cultural advisory boards,

restricted heritage datasets. |

In this case, it is about commercial AI sites using cultural heritage data sets like folk art motifs, weaving patterns, and tribal designswithout paying the communities that made them as indicated in Table 3. The use of these datasets was usually non-commercial AI training, whether as archives or for educational purposes. Monetization of outputs on the basis of such data done by AI companies amounted to a kind of cultural extraction. The case shows the vulnerabilities in the data sovereignty and ethical duties of the AI creators to the marginalized society. The necessity of benefit-sharing contracts, community-based regulations of the dataset, and cultural licensing are realized.

5. Algorithmic Decision-Making and Ethical Risk Assessment

The analytical findings of the four graphical assessments will give a holistic idea of how AI-based algorithmic decision-making can influence ethical conclusions in AI art. The results shed light on the relationship between the composition of datasets, model structure, prompt design and platform governance eventually, where ethical vulnerabilities are found and how they can be addressed. The trends that can be traced in Figure 7 up to 7.4 as a whole emphasize the systemic issues related to generating AI systems and underline the importance of multi-layered ethical protection.

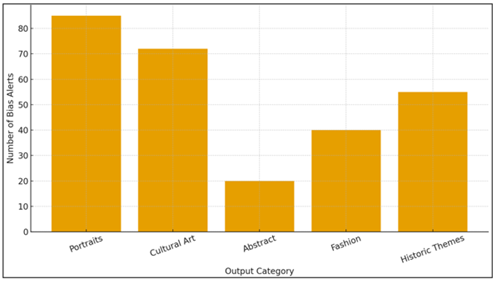

Figure 4

Figure 4 Bias Detection Frequency Across Output Categories

Figure 4 below shows the bias alerts that occurred in the creation of the various types of AI-assisted artworks. The findings indicate that cultural art types and portraits have the most common frequency of identified biases and, therefore, demographic and cultural representations create the greatest ethical threat to the generative models as outlined in Table 4. This is happening as a result of the underlying imbalances in training data, in which the demographic overrepresentation tends to cause the algorithm to favor facial features, skin tones or cultural patterns.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Risk Classification Matrix Based on Output Type and Prompt Complexity |

|||

|

Output

Type |

Low

Complexity Prompt |

Medium

Complexity Prompt |

High

Complexity Prompt |

|

Portraits |

Medium

Risk |

High

Risk |

Very

High Risk |

|

Cultural Art |

Medium Risk |

High Risk |

Extreme Risk |

|

Abstract

Art |

Low

Risk |

Low

Risk |

Medium

Risk |

|

Fashion / Aesthetic |

Low Risk |

Medium Risk |

High Risk |

|

Historic

/ Religious Themes |

Medium

Risk |

High

Risk |

Extreme

Risk |

On the other hand, the number of bias alerts in abstract art is the fewest because the non-representational features of the art make it less likely to be misinterpreted due to demographic or cultural reasons. Straddling between moderate degrees of contextual, or representational sensitivity, are historic themes and fashion. In general, categories of distribution focus on the significance of specific auditing and bias reduction measures on material belonging to individual content types or containing identifiable human qualities or culturally contextualized imagery.

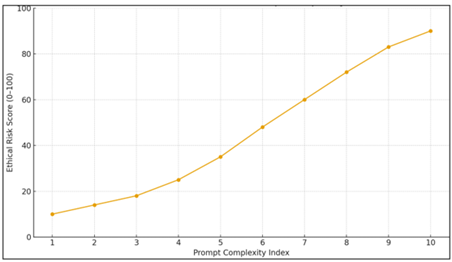

Figure 5

Figure 5 Ethical Risk Score vs. Prompt Complexity

Figure 5, shows us the growth of ethical risk as the prompt complexity is increasing. The more the prompts are replaced by the word with complex instructions that mention certain identities, cultural phenomena, or symbolic situations, the higher the ethical risk is. The graph shows that the level of risk is rather linear initially (risk is relatively low when simple prompts are used like draw a sunset) but the growth rate rises dramatically when culturally specific prompts are used (bs depict an indigenous ceremony in Renaissance style).

Table 5

|

Table 5 Semantic Layer Ethical Vulnerability Index |

|||

|

Model

Layer |

Ethical

Vulnerability |

Typical

Issues |

Governance

Needed |

|

Early

Layers |

Low |

Basic

feature extraction |

Minimal |

|

Mid Layers |

Moderate |

Texture/style blending |

Monitoring + filters |

|

High-level

Semantic Layers |

Very

High |

Symbol

misrepresentation, stereotype formation |

Explainability

+ cultural safeguards |

|

Safety Filters |

Medium |

Detection limits, false

negatives |

Strengthen rules and human review |

This positive trend suggests that finer prompts lead to more algorithmic interpretation and are more likely to reproduce stereotypes, misrepresent the situation or give culturally inappropriate syntheses as shown in Table 5. The graph highlights the necessity of intensive risk assessment tools that can identify the ethically sensitive factors in multifaceted prompt structures.

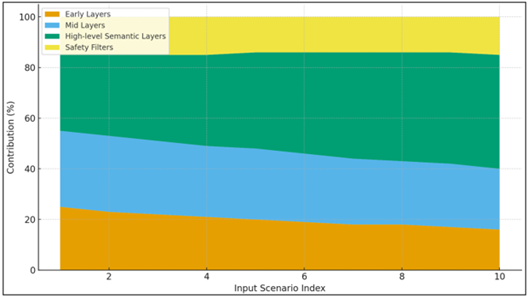

Figure 6

Figure 6 Contribution of Model Layers to Final Output

Figure 6 illustrates the contribution ratio of various model layers deep layers, middle level layers, uppermost semantic layers and safety filter to the overall output of the generator. The figure shows that the early and mid-level layers become less influential as the input scenarios get more and more semantically rich, and the semantic layers of decision-making become dominated by the high-level semantics. This change is observed to be indicative of how the model depends on deep associative structures in generating conceptually complex images. Safety filters have a relatively consistent contribution in all scenarios, so they guarantee compliance at the baseline, as well as, counteract detrimental outputs. This stratified meaning draws attention to the need to put ethical evaluation efforts within the higher levels of semantic processing units where culturally sensitive or representational judgments are made.

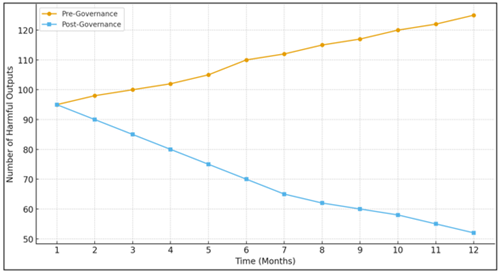

Figure 7

Figure 7 Harmful Output Frequency Over Time Before and After

Governance

Figure 7. compares the frequency of harmful output of the system prior to and after governance models like bias filters, limited prompts, supervised review, and cultural sensitivity checks. The pre-governance line shows that malicious output production has gradually improved with time, probably owing to model drift, experimentation, and absence of remedial restrictions. The post-governance curve, in turn, demonstrates an upward trend, which indicates the beneficial effect of the implemented ethical controls. These findings demonstrate that governance schemes in particular, the use of human-in-the-loop review and high-level semantic safety filtering greatly decreases destructive products or sensitive ones. The figure confirms the thesis that ethical governance systems are important in ensuring safe and responsible AI art systems.

In general, the conglomerate analysis of these four graphs sheds light on one of the main conclusions: ethical threats in AI art can be predicted, diagnosed, and controlled when treated as a compound. Identity and culture-focused outputs form the most biased domain; the risk increases with the complexity of semantics; the interpretability gap is concentrated around the high-level semantic layers; and the extensive use of systematic governance can significantly decrease the amount of harmful outcomes. It is on the basis of these lessons that more responsible systems with greater cultural sensitivity can be constructed with more openness and fairer treatment of creative contributors. Ethical governance needs to be covered with a multi-layered method combining dataset audits, timely-risk scoring, semantic-layer supervision, and ongoing monitoring in order to make sure that innovative AI technologies do not go against human values and social standards

6. Conclusion

This paper discussed the ethical issues associated with AI-generated artworks, and they showed that risks are not individual errors but internal to the system based on the composition of the dataset, the model architecture, and design of governance. Generative process analysis demonstrated that the top layer of semantic representations are the main culprits of representational bias, cultural misrepresentation, stereotyping, while dataset disproportions generate demographic discrimination and unauthorized copying of style. These results verify that AI models are the most vulnerable to ethical challenges when they work with identity-related, culture-specific, or symbolically sensitive domains of content where computational systems do not have contextual knowledge. These structural issues were also demonstrated in the five case studies in the way they manifested in practice. Cultural appropriation of style denies the artist autonomy; cultural and spiritual damage through misrepresentation of sacred cultural motifs; biased demographic portraits, exploitation of datasets of community-generated heritage revenue, and deep fake images pose a threat to privacy, institutional trust and social stability. It is also found in the analysis that the governance interventions, transparent datasets, style and identity protection filters, cultural-sensitivity layers, fairness auditing, and structured human oversight significantly minimize the harmful outputs when applied consistently. However, the fast development of generative AI demands that its regulation change not only the traditional, rule-based actions but adopt dynamic, situational regulations that are responsive to the risks emerged. It is also important that artists, cultural communities, policymakers, and technologists play an active role in the design of governance mechanisms that limit different values and lived experiences. The systems of the future should not solely cause the least damage, but also contribute to the preservation of the culture, fair representation, and inclusive creativity. To make sure that the creative technologies are respectful, accountable, and in line with the society and cultural values, it is vital to embed the ethics into the central nature of generative AI development.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Acion, L., Rajngewerc, M., Randall, G., and Etcheverry, L. (2023). Generative AI Poses Ethical Challenges for Open Science. Nature Human Behaviour, 7, 1800–1801. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01740-4

Baldassarre, M. T., Caivano, D., Fernandez Nieto, B., Gigante, D., and Ragone, A. (2023). The Social Impact of Generative AI: An Analysis on ChatGPT. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Information Technology for Social Good (363–373). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3582515.3609555

Chan, C. K. Y., and Hu, W. (2023). Students’ Voices on Generative AI: Perceptions, Benefits, and Challenges in Higher Education. arXiv Preprint. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00411-8

Hurlburt, G. (2023). What if Ethics Got in the Way of Generative AI? IT Professional, 25, 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/MITP.2023.3267140

Lee, K., Cooper, A. F., and Grimmelmann, J. (2024). Talkin’ ’Bout AI Generation: Copyright and the Generative-AI Supply Chain (short version). In Proceedings of the Symposium on Computer Science and Law (48–63). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3614407.3643696

Li, F., Ruijs, N., and Lu, Y. (2023). Ethics and AI: A Systematic Review on Ethical Concerns and Related Strategies for Designing with AI in Healthcare. AI, 4, Article 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai4010003

McCradden, M. D., Stephenson, E. A., and Anderson, J. A. (2020). Clinical Research Underlies Ethical Integration of Healthcare Artificial Intelligence. Nature Medicine, 26, 1325–1326. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1035-9

McKinley, G. A., Acquaviva, V., Barnes, E. A., Gagne, D. J., and Thais, S. (2024). Ethics in Climate AI: From Theory to Practice. PLOS Climate, 3, e0000465. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000465

Montomoli, J., Bitondo, M. M., Cascella, M., Rezoagli, E., Romeo, L., Bellini, V., Semeraro, F., Gamberini, E., Frontoni, E., and Agnoletti, V. (2024). Algor-Ethics: Charting the Ethical Path for AI in Critical Care. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing, 38, 931–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-024-01157-y

Morley, J., Elhalal, A., Garcia, F., Kinsey, L., Mokander, J., and Floridi, L. (2021). Ethics as a Service: A Pragmatic Operationalisation of AI Ethics. Minds and Machines, 31, 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-021-09563-w

Murphy, K., Di Ruggiero, E., Upshur, R., Willison, D. J., Malhotra, N., Cai, J. C., Lui, V., and Gibson, J. (2021). Artificial Intelligence for Good Health: A Scoping Review of the Ethics Literature. BMC Medical Ethics, 22, Article 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00577-8

Nah, F. F.-H., Cai, J., Zheng, R., and Pang, N. (2023). An Activity System-Based Perspective of Generative AI: Challenges and Research Directions. AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction, 15, 247–267. https://doi.org/10.17705/1thci.00190

Rhim, J., Lee, J.-H., Chen, M., and Lim, A. (2021). A Deeper Look at Autonomous Vehicle Ethics: An Integrative Ethical Decision-Making Framework to Explain Moral Pluralism. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 8, Article 632394. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2021.632394

Sandiumenge, I. (2023). Copyright Implications of the Use of Generative AI (SSRN Working Paper No. 4531912). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4531912

Tang, L., Li, J., and Fantus, S. (2023). Medical Artificial Intelligence Ethics: A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies. Digital Health, 9, 20552076231186064. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231186064

Thambawita, V., Isaksen, J. L., Hicks, S. A., Ghouse, J., Ahlberg, G., Linneberg, A., Grarup, N., Ellervik, C., Olesen, M. S., Hansen, T., et al. (2021). DeepFake Electrocardiograms Using Generative Adversarial Networks are the Beginning of the End for Privacy Issues in Medicine. Scientific Reports, 11, Article 21896. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01295-2

Voss, E., Cushing, S. T., Ockey, G. J., and Yan, X. (2023). The use of Assistive Technologies Including Generative AI by Test Takers in Language Assessment. Language Assessment Quarterly, 20, 520–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2023.2288256

Zhong, H., Chang, J., Yang, Z., Wu, T., Arachchige, P. C. M., Pathmabandu, C., and Xue, M. (2023). Copyright Protection and Accountability of Generative AI: Attack, Watermarking and Attribution. In Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023 (94–98). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3543873.3587321

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.