ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Reinventing Artistic Identity in the Age of Algorithms

Dr. Rahul Amin 1![]()

![]() ,

Swati Srivastava 2

,

Swati Srivastava 2![]() , Manpreet Singh 3

, Manpreet Singh 3![]()

![]() , Bharat Bhushan 4

, Bharat Bhushan 4![]()

![]() , Dr. Jairam Poudwal 5

, Dr. Jairam Poudwal 5![]()

![]() , Ashutosh Pandey 6

, Ashutosh Pandey 6![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, ARKA JAIN

University Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

2 Associate

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University,

Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 Centre of Research Impact and

Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, India

4 Chitkara Centre for Research and

Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

5 Assistant Professor, Department of

Fine Art, Parul Institute of Fine Arts, Parul University Vadodara, Gujarat,

India

6 United Institute of Management, Prayagraj, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The concept of

artificial intelligence is transforming the principles of artistic practice

by breaking the old assumptions about the creative process, authorship, and

aesthetic value. The paper discusses the phenomenon of emerging hybrid

artistic identity in the era of algorithms by providing a comprehensive study

of history and evolution, theory, sociocultural processes, and ethical and

legal imperatives. It considers that the art identity is no longer a unique,

man-made machinery but a distributed mechanism in which the creative agency

is a collaboration of human intention and computational processes of

generative algorithms. The paper develops the most important theoretical

ideas, such as distributed intention, algorithmic aesthetics, posthuman

creativity, and procedural meaning-making to provide the understanding of how

AI-based artworks are dissimilar to the traditional human-based models of

expression. Empirical comparisons over visual features and emotional value

show the presence of distinctive aesthetic differences between human and

machine output which highlight the appearance of computationally native forms

that are influenced by the latent-space representation and not based on

subjective experience. The paper also examines the key sociocultural effects

of AI art, including the democratization of access to creativity,

oversaturation of the market, the change in the understanding of

authenticity, and the transformation of art education. The essential ethical

and legal issues such as provenance of datasets, authorial responsibility,

cultural bias, and unclear copyright status of AI-generated are discussed in

order to highlight the necessity of clear regulatory frameworks and

culturally diverse datasets. Multimodal AI systems, self-evolving generative models,

and collaborative human-AI creative platforms are some of the future

directions being pursued, which will continue to influence the production,

curation, and experiences of art. The research paper comes to the conclusion

that AI is not something that is going to displace human creativity but

rather a transformational companion that broadens the conceptual and

expressive limits of art. The age of algorithms is eventually heralding a new

paradigm of fluid artistic identity, based on relations and technologically

co-constructed. |

|||

|

Received 14 February 2025 Accepted 08 May 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. Rahul

Amin, dr.rahul@arkajainuniversity.ac.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6737 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Hybrid Artistic Identity, Algorithmic Creativity,

Generative Models, Computational Aesthetics, Posthuman Creativity,

Distributed Authorship, Machine-Native Aesthetics |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

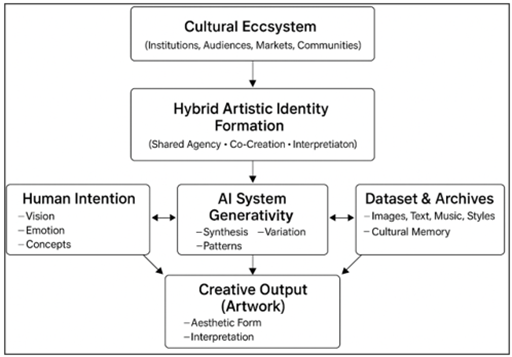

Modern creative practice has reached a critical point in its development due to the increased pace of inclusion of an artificial intelligence in the process of creating art. Traditionally, artistic identity is based on the unique human creator a figure demanded by subjective experience, emotional richness Benjamin (1999), cultural memory and willed expression. The artist is also viewed as an autonomous agent, whose imaginations influences material, technique, and concept with creative works of art. However, with the machine learning systems continuing to showcase their capacity to produce images, create music, form stories, and replicate sophisticated aesthetic patterns, the practice of traditional demarcations that defined artistic identity is being reconfigured in a fundamental way Ziff (1953). Generative algorithms especially deep neural networks, diffusion models, multimodal transformers, has relegated AI not as a digital tool but as an active agent of the creative process. Unlike the previous visual forms of computational art, which were characterized by deterministic inputs and rule based automation, the current models of AI are adaptive in nature, probabilistic in imagination and have the potential to produce novel output that does not directly imitate and/or explicitly reference any one human aesthetic. The changes compel artists and theorists to face the critical questions: What is creativity in the context of algorithmic input of choices related to style? So how can human will exist with computational autonomy? Is it possible to preserve the idea of artistic identity in a world where the agency is spread among human beings and non-human beings? Zeilinger (2021). Instead of being a harbinger of the loss of human creativity, AI brings new relations to human society in which artistic identity becomes hybrid, co-constructed, and multilayered. Artists have ceased being artists as they are now arrangers of algorithmic possibilities who curate datasets, set up models, reformulate prompts and interpret machine generated variations. AI, in its turn, can be viewed as an aesthetic amplifier Cima (2015), providing the unexpected structures, creating alternative patterns, and broadening the conceptual field in the process of rapid repetition. This participatory game displays an artistic identity not in the form of a definite character but rather in the form of a dynamic, changing association between human intentionality, computational generativity and the cultural interpretation Davis et al. (2014).

Figure 1

Figure 1

Human–AI Interaction

Model in Artistic Identity Formation

The emergence of AI art is not confined to the efforts of individual artists and also affects the socio-cultural and institutional context. Museums, galleries and creative industries are reviewing the principles of authorship, originality and artistic value. The expectations of the audience are also changing with the increase of works of art whose emotional appeal is no longer associated with human intent Hutson and Lang (2023). These changes force the new discourse of art to embrace new theoretical approaches of posthumanism, computational creativity studies, and culture analytics to comprehend how newer forms of identity, agency, and authorship are being transformed in the algorithmic age. This introduction places the study in this interdisciplinary terrain by exploring how the issue around artificial intelligence challenges, grows and finally reshapes the definition of artistic identity. It claims that the era of algorithms is not the end of artistic performance or the loss of creative values but rather, it is a call to re-consider creative performance as collective, networked and hybridized phenomenon Chiu et al. (2022). Learning about this shift is crucial to creating new critical vocabularies, ethical issues and aesthetic paradigms to work in an age where machines and human beings are more and more co-creating.

2. Historical Evolution of Artistic Identity

The process of artistic identity formation has never been fixed, but instead it has changed in tandem with culture values, technological advancement and the various interpretations of creativity. In the early and classical civilizations, the arts were mainly incorporated into social, spiritual or ritualistic settings of the community. The artist was mostly anonymous and the skill of craftsmanship was important as compared to individuality Xu and Jiang (2022). Creativity was seen as a gift of the divine and the artist as the interceder between divine inspiration and matter. This initial era defined art as a shared culture in common and not the individual mark of a solo mind. Renaissance was a radical shift in the veneration of personal artistic genius. This period formed the basis of contemporary concepts of artistic independence. Romanticism changed the image of a painter to that of a man whose creativity was motivated by emotions and was artistically spiritual Kalniņa et al. (2024). Romantic artist was renowned as the embodiment of inner anguish, experience, and transcendent feeling. Creativity was perceived to be a result of psychological depth and real selfhood and this gave credence to the fact that the value of art lay in the individuality behind it Atif et al. (2021). This structure continued into modernism which pushed the emphasis on originality, abstraction and experimentation. The creative identity became more associated with a stylistic dislocation and seeking new aesthetic forms of expression Alotaibi (2024).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Historical Shifts in Artistic Identity |

|||

|

Era

/ Period |

Dominant

View of the Artist |

Source

of Creativity |

Concept

of Identity |

|

Ancient

/ Classical |

Anonymous

craftsperson |

Divine

inspiration, communal expression |

Collective

and tradition-bound |

|

Renaissance |

Master individual |

Skill, observation,

innovation |

Personal artistic genius |

|

Romanticism |

Emotional

visionary |

Inner

emotion, spiritual depth |

Authentic

selfhood |

|

Modernism |

Radical experimenter |

Formal innovation,

abstraction |

Individual originality |

|

Postmodernism |

Conceptual

provocateur |

Appropriation,

critique, context |

Distributed,

fragmented author |

|

AI Age |

Human–machine co-creator |

Generative modeling,

datasets, algorithms |

Hybrid, shared agency |

Postmodern movement in the twentieth century disrupted the traditional authorship by bringing about fragmentation, appropriation, and intertextuality. Artists like Duchamp questioned the purity of originality and thought that the context, understanding and conceptual framing were equally or more important Tedre et al. (2023). Nevertheless, the human being in post modernism was still the main performer whether as an author, collector, critic or instigator. The implementation of artificial intelligence in creative practice is the first step in the cultural history when the creative agency is no longer human. In contrast to other tools that have been used in the past, AI presents generative and decision-making abilities Lim et al. (2023). The current machine-learned aesthetic results, which are generated based on large cultural datasets, are complex and can disrupt the conventional association between identity and authorship. This transformation puts artistic identity in a distributed system of human intention, generativity through algorithms, and memory within the dataset that is held in common.

3. Theoretical Foundations: Creativity, Agency, and Algorithmic Mediation

Artistic identity of the era of algorithms is based on the unity of studies of creativity, post humanist philosophy, media theory, and computational agency. Conventionally aesthetic theory has always based creativity on the intentionality of the human, emotional richness and the ability to imaginatively change. This anthropomorphic model places the artist at the most central point of meaning-making in which the individual sensibility, experience of life and cultural localization are all brought together to constitute artistic identity Ernesto and Gerardou (2023), Ivanov and Soliman (2023). The introduction of artificial intelligence into creative practice, however, disrupts these frameworks by introducing new non-human ways of generativity. In the eyes of the computational creativity theory, AI models are not passive devices, but systems that can discover patterns, synthesize styles as well as create imaginative exercises that are probabilistic. Even though these systems are consciousness and do not align with the subjective intent, the fact that they can produce new forms of aesthetics makes it contend able to reexamine the processes in which creativity works. In this broader sense, creativity is not only dependent on internal processes, but may be created by complicated interplay between data, algorithms, and human interpretation. This is consistent with the distributed cognition theories which state that cognitive processes do not only take place in the mind, but also in the tools and environments in which thinking takes place.

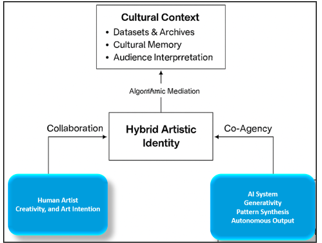

Figure 2

Figure 2 Distributed Agency Framework

Relational and post humanist ontologies also offer theoretical foundations on the perception of hybrid artistic identity. N. Katherine Hayles and other scholars like Donna Haraway believe that agency is not human only but is shared in networks of human and non-human actors. In this context, artistic identity is an emergent quality that is determined by the relations between artists, datasets, algorithms, cultural memory, and the audience. This makes AI a co-agent instead of a tool whose power is that of its computational form, training data, and ability to generate as illustrated in Figure 2. The media theory adds another dimension that illustrates the way in which technologies transform cultural production. This statement of Marshall McLuhan that a medium is a message is especially fitting: not only the formation of images is affected by the architecture of AI systems neural layers, latent spaces, diffusion processes, but also meaning formation Winner (1997), Yang (2022). Algorithms mediation therefore becomes an inseparable part of recognizing the current artistic identity in that the role of the artist is changed to that of a creator, curator, and translator of the computational results.

4. Algorithmic Creativity: Mechanisms, Models, and Aesthetic Implications

Development of algorithmic creativity is one of the most radical conceptual transformations of the modern art that has radically changed the manner the creative process is initiated, developed, and assessed. Contrary to the traditional form of creative expression, that is rooted in the phenomenological experiences and desires of the artist, algorithmic creativity is based on data-driven computation, probabilistic modeling and generative learning. This part discusses how the algorithmic creativity works, the models that make it possible and the aesthetic consequences that come along with the involvement of machines in the creative process. These systems get trained on patterns, stylistic structures, and representations structures of the huge datasets and create latent spaces, which encode the statistical character of aesthetic forms. More importantly, this creativity is not creative because it is based on mathematical maximization and representational interpolation. The development of GANs brought a major breakthrough in machine-created aesthetics, as it made possible the adversarial learning process, in which a generator and a discriminator mutually enhance each other, due to active feedback. The output of such a dynamic has a high level of realism or stylistic fidelity. VAEs and diffusion models, in their turn, are offering much smoother and interpretable latent spaces, where the style, composition, and semantic structure can be manipulated with control.

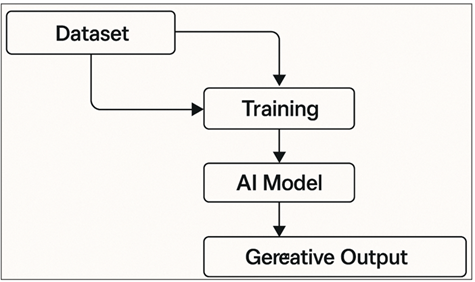

Figure 3

Figure 3 How Algorithmic Creativity Works

Algorithms increase the expressive limits of humans aesthetically. The machines have the capability of creating hyperreal textures, impossible geometries and structural permutations beyond the human intuition. In addition, the appearance of algorithmic variation allows artists to think quickly and refine their ideas further, moving through thousands of conceptual paths in several minutes Zuboff (2019). However, such abundance creates issues of creativity and philosophy. One of the ways to transform the functions of an artist is that when machines create unlimited possibilities, the artist becomes a selecter, a curator, a meaning-maker. The innovation process is turned into a process of filtering as illustrated in Figure 3, contextualizing, and interpreting the output of an algorithm, instead of building each component separately. Algorithms creativity creates issues of authorship, novelty and aestheticism as well. Since machine-generated results are based on statistics of the training data, there is a high risk that they will replicate existing cultural patterns without critical comment. Besides, the aesthetic choices that are encoded in model architectures the choice of datasets, hyperparameters and loss functions determine the end result of the art as any human gesture. These veils of influence make the attribution of creative identity more complex and human and computational agency are encoded into the end aesthetic object.

5. Proposes System Aesthetic Transformations in AI Art Algorithm

Introduction of the artificial intelligence into the creative practice has produced radical aesthetic changes that set against the traditional concept of style, visual language, and expressive possibility. In contrast to previous technological changes (say, photography or digital image AI does not just expand the range of technical abilities of the artist) it brings in the independent generative processes that transform the aesthetic field directly. These changes are brought about by the fact that the AI systems operate based on the patterns (uniqueness) of perception, learning, and recombining in large volumes of data thus creating artistic products that do not follow the traditional human pattern of creation.

Step 1: Cultural Data and Feature Space Construction

Let the dataset of artworks (images, but could be multimodal) be

![]()

where H,WH, are height and width, CCC channels (e.g., 3 for RGB).

A feature extractor (often a deep CNN)

![]()

maps each artwork into a feature space:

![]()

This philosophical (implanted aesthetic) (color composition, shapes, textures, style).

The appearance of machine-native aesthetics of visual or sonic qualities that are not based on the human experience itself but on the computational logic of neural networks is one of the most important aesthetic transformations. Latent-space blending, fractal distortions, spectral textures, and diffusion-based formations are some of the phenomena introducing new aesthetic vocabularies which are familiar and alien at the same time.

Step 2: Latent Representation and Aesthetic Manifold

We suppose that the artworks are on (or near to) a low dimensional manifold in feature space.

Introduce a latent space Z⊂Rk

A generative model (VAE, GAN, diffusion, etc.) learns a mapping

![]()

Attempts to estimate posterior q (z 10 ). Then the latent

aesthetic aesthetic latent manifold learned by the culture is approximated by

the set of encoded existing artworks ![]()

These models tend to expose the mathematical underpinnings of AI models, creating the artworks that may seem to be guided by computational intuition more than human common sense. The outcome is a category of aesthetic that is not characterized by intentional expression but through the use of an algorithm to pattern.

Step 3: Learning Generative Structure (Training

Objective)

Minimizing a loss, which encodes reconstruction, realism and in some cases style, learns the model parameters θ, ϕ.

Input: Sizes, Structure, and Learning Rates.

![]()

Example: GAN Loss (Adversarial Realism)

Generator Gθ, discriminator Dψ

![]()

6. Sociocultural Impacts Analysis of AI-Driven Art

Artificial intelligence also greatly increases access to creative expression because it reduces technical and material barriers that are traditionally linked to artistic production. The use of tools like text-to-image generators helps an untrained person to create what can be considered a visually advanced piece of art. Such democratization gives power to new creative communities especially on-line where users collaboratively search through generative aesthetics, share outputs, and fine-tune prompts.

Nonetheless, such transparency also blurs professional and amateur boundaries between artistic professionals and amateurs. The access to strong AI technologies changes the cultural understanding of what is considered to be a skill, mastery, and creative right. Although AI expands access, it floats the digital art platforms with enormous amounts of generated art. The fact that AI can create thousands of images within seconds, makes the traditional artists less visible in the flooding marketplaces. Cultural organizations are also forced to consider the value of cultural recognition and curation anew where scarcity, craftsmanship, and manual technique is no longer a strong measure of quality. This change puts pressure on galleries, festivals and curators to come up with new models to define meaningful contribution of art in algorithmic rich environments.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Style Clustering of AI-Generated vs Human Artworks

This Figure 4 shows the grouping of visual style characteristics in works of art differently when determined by AI systems or by human artists. The cluster of AI (orange) is smaller and more centralized, which implies that the algorithmic styles exhibit a higher level of internal similarity as they are based on the learned patterns using training datasets. The human cluster (blue) is more diffused, in contrast, indicating the broader stylistic diversity based on the cultural context, individual interpretation, emotional intention and lived experience. The distinct distinction between the clusters suggests that AI and human creative processes give rise to a distinct aesthetic signature, which lends the point of view that the machine-native aesthetic has structural differences with the human-centric one. The classical notions of authenticity, expressiveness, and intentionality are made complex by the AI-generated art. Audiences tend to resonate emotionally in AI images even though they know that human subjectivity did not create them.

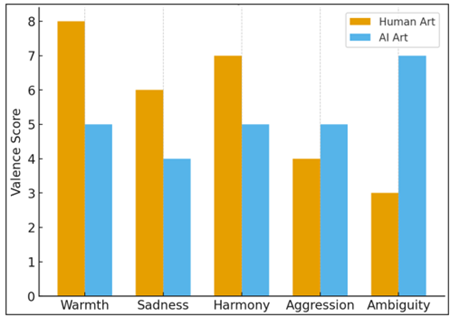

Figure 5

Figure 5 Emotional Valence Comparison Between Human and AI

Art

The difference in the expressiveness of emotions in human and algorithmic artworks are indicated by the bar char in Figure 5. The values of human art tend to be more warm, sad, and harmonious, which proves that the depth of emotions, subjective experience, and the intention to express something remain the key human capabilities. However, AI-created art works better in terms of aggression and ambiguity in particular, meaning that machine-made art can produce mixed or vague emotions. This is in line with what theoretical assertions hold as AI having no embodied emotional experience but a simulated one based on approximating patterns instead of experience affect. The extreme supports the theoretical distinction between synthesis of emotional intentionality of humans and computational aesthetic synthesis. Generative models are biased by the culture in which they were trained. The dominant art forms in mainstream, Western, and highly digitized art have controlled the model modes of learning, and those that are marginalized or underrepresented can be downplayed or changed. These moving powers shape the memory of culture as they dictate what visual customs are intensified and which are no longer seen in the outputs of AI. With the increasing role of AI in visual culture, it acquires the ability to transform aesthetic canons and create norms, along with the ability to alter the symbolic representation of communities and to do so subtly.

Figure 6

Figure 6 Aesthetic Coherence Across Training Epochs

This line graph, which is presented in Figure 6, demonstrates the way that a neural generative model becomes more aesthetically expressed with the increase of training. The results of early epochs are of low coherence because the output is characterized by noise since the models are not sufficiently trained. The more the training develops, the more the structural relationship, the style, and compositional balance in its training data are reflected in the model. The coherence scores increase exponentially by the later epochs indicating the capability of the model to generate more meaningful and picture-consistent images. Stochastic optimization is likely to cause minor fluctuations, however, they do not interfere with the overall upward trend. This visualization is empirical evidence of the way algorithmic creativity develops as a result of iterative learning and not deliberate refinement which is the difference between machine learning and human experiential development. Artificial intelligence has impacted the learning process, practice, and way of thinking of young artists. On the one hand, generative models allow students to experiment fast by providing students with the opportunity to try different compositions and stylistic paths within a short period of time. Conversely, excessive use of AI can decrease the possibility of practical experience, undermine the primary artistic abilities, drawing, composition, and material sensitivity.

7. Conclusion

The emergence of artificial intelligence as a creative agent that is active is one of the most crucial changes in the history of the artistic practice. As it has been indicated in this paper, AI does not merely present new tools but alters underlying principles by which art, identity, authorship and cultural value are perceived. Since the history of artistic identity has already been developed through the formation of hybrid forms of human-machine co-creativity, AI is pushing the limits and making people reconsider the concept of creativity as a phenomenon of distribution, relationship, and multi-layering. The theoretical discussion of distributed intention, algorithmic aesthetics and posthuman creativity demonstrate that modern art is increasingly produced as a result of the interaction between human conceptual vision, computer computations, and culture information. This transition indicates the fact that artistic identity in the age of algorithms is not diminished and replaced but enlarged. It turns hybrid, fluid and co-constructed dynamically in terms of technology, culture and morality. Simultaneously, the use of AI in the context of creative ecosystems is a pressing ethical, legal, and sociocultural concern. Frauds on authorship, dataset provenance, culture representation and labour displacement are some of the questions that necessitate responsible governance. With the rise of generative systems, policymakers, institutions, and artists have to collaborate to secure a fair pay, open development process and cultural diversity. Further development of multimodal AI, self-evolving models and interactive creative systems will further revolutionize the way that art is created, taught, curated and experienced. The future of artistic identity will be predetermined by the new variants of cooperation in which human sensibility and the computational imagination can exist simultaneously. Finally, algorithms are not a menace to the art, but a new playing field in which creativity can develop that opens up new aesthetic opportunities and re-purposes the artist in a mediated world in which technology plays a significant part.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Alotaibi, N. S. (2024). The impact of AI and LMS Integration on the Future of Higher Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Strategies for Transformation. Sustainability, 16, Article 10357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310357

Atif, A., Jha, M., Richards, D., and Bilgin, A. A. (2021). Artificial Intelligence Enabled Remote Learning and Teaching Using Pedagogical Conversational Agents and Learning Analytics. In Intelligent systems and learning data analytics in online education (3–29). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823410-5.00013-9

Benjamin, W. (1999). Little History of Photography. In M. W. Jennings, H. Eiland, and G. Smith (Eds.), Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings (Vol. 2, pp. xx–xx; M. W. Jephcott and K. Shorter, Trans.). Belknap Press.

Chiu, M. C., Hwang, G. J., Hsia, L. H., and Shyu, F. M. (2022). Artificial Intelligence-Supported Art Education: A Deep Learning-Based System for Promoting University Students’ Artwork Appreciation and Painting Outcomes. Interactive Learning Environments, 32, 824–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2100426

Cima, R. (2015, April 24). How Photography was Optimized for White Skin Color. Priceonomics.

Davis, A., Rubinstein, M., Wadhwa, N., Mysore, G. J., Durand, F., and Freeman, W. T. (2014). The Visual Microphone: Passive Recovery of Sound from Video. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 33, Article 79. https://doi.org/10.1145/2601097.2601119

Ernesto, D., and Gerardou, F. S. (2023). Challenges and Opportunities of Generative AI for Higher Education as Explained by ChatGPT. Education Sciences, 13, Article 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090856

Hutson, J., and Lang, M. (2023). Content Creation or Interpolation: AI Generative Digital art in the Classroom. Metaverse, 4, Article 13. https://doi.org/10.54517/m.v4i1.2158

Ivanov, S., and Soliman, M. (2023). Game of Algorithms: ChatGPT Implications for the Future of Tourism Education and Research. Journal of Tourism Futures, 9, 214–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-02-2023-0038

Kalniņa, D., Nīmante, D., and Baranova, S. (2024). Artificial Intelligence for Higher Education: Benefits and Challenges for Pre-Service Teachers. Frontiers in Education, 9, Article 1501819. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1501819

Lim, W. M., Gunasekara, A., Pallant, J. L., Pallant, J. I., and Pechenkina, E. (2023). Generative AI and the Future of Education: Ragnarök or Reformation? A Paradoxical Perspective from Management Educators. The International Journal of Management Education, 21, Article 100790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100790

Tedre, M., Kahila, J., and Vartiainen, H. (2023). Exploration on How Co-Designing with AI Facilitates Critical Evaluation of Ethics of AI in Craft Education. In Proceedings of the SITE International Conference 2023 (2289–2296).

Winner, L. (1997). Cyberlibertarian Myths and the Prospects for Community. Computers and Society, 27, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1145/270858.270864

Xu, B., and Jiang, J. (2022). Exploitation for Multimedia Asian Information Processing and Artificial Intelligence-Based Art Design and Teaching in Colleges. ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing, 21, Article 114. https://doi.org/10.1145/3526219

Yang, Z. (2022, November 22). China Just Announced a New Social Credit Law. Here’s What it Means. MIT Technology Review.

Zeilinger, M. (2021). Tactical Entanglements: AI Art, Creative Agency, and the Limits of Intellectual Property. Meson Press.

Ziff, P. (1953). The Task of Defining a Work of Art. The Philosophical Review, 62, 58–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/2182722

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.