ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Using AI to Trace Regional Art Lineages

Harsimrat Kandhari 1![]()

![]() ,

Sanjivani Deokar 2

,

Sanjivani Deokar 2![]() , Pancham Cajla 3

, Pancham Cajla 3![]()

![]() ,

Swati Srivastava 4

,

Swati Srivastava 4![]()

![]() ,

Pooja Bhatt 5

,

Pooja Bhatt 5![]()

![]()

1 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan, 174103, India

2 Department

of Computer Engineering, Lokmanya Tilak College of Engineering, Mumbai

University, Maharashtra, India

3 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

4 Associate Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International

University 2032015

Assistant Professor, Department of 5 Computer Science and Engineering, Faculty

of Engineering and Technology, Parul Institute of Engineering and Technology,

Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

utilization of artificial intelligence (AI) in art-historical studies has

revolutionary potential of understanding the way of how regional art

traditions evolve and interrelate. In this paper, the advantages of applying

computational approaches to tracing artistic traditions across time and

culture are examined, especially through image recognition, neural networks

and information-guided ontologies. The combination of art-historical concepts

of descent, impact, and place-making with current visual semiotics, pattern

recognition resulted in the creation of the framework that allows

interpreting stylistic development in an algorithmic manner. The theoretical

background highlights the essence of the digital methodologies that not only

complement the traditional historiography, but also transform the paradigms

of the interpretation of cultural heritage. The technological aspect of this

work explores AI models, which can help detect visual repetitions, stylistic

continuations, and regional differences in data collections on digital

museums and art repositories. The aspects of creation and curation of

training datasets are considered, along with ethical concerns of cultural

bias in the algorithmic learning. The study plan comprises of case-studies of

the chosen regional art genres in order to build an AI pipeline that

visualizes the genealogies of style, providing an objective measure of the

aesthetical impact and change. In conclusion, this paper has shown that AI

can be used as a tool of analysis and curation, in order to promote the

documentation, conservation and sharing of local art heritage. Its wider

ramifications apply to the field of educational innovation, museum curation,

and digital humanities, implying that algorithmic approaches can have a

constructive impact on art historiography, helping to understand other

cultures and explaining the way arts are happening in the world. |

|||

|

Received 20 February 2025 Accepted 14 May 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Harsimrat

Kandhari harsimrat.khandari.orp@chitkara.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6725 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Artificial

Intelligence, Art Lineage, Visual Semiotics, Neural Networks, Cultural

Heritage, Regional Art History |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The diversity of art in its regionalism

is the collective memory of culture, experience of history, the evolution of

aesthetic. Every artistic practice, be it painting, sculpture, textile design

or architecture has built within it stories of identity and power, which unite

communities throughout time and space. Tracking down of these lineages or

stylistic, thematic and technical continuities that characterize regional art

has been a major concern of art historians. Historically, the task has been

dependent on human perception: the connoisseurial eye of the trained seeing

similarities in composition, color scheme, iconography or material method. But

now that art history is finally going digital, Artificial Intelligence (AI)

provides the means to radically change the limits of analysis of the lineage by

revealing all sorts of complicated visual and cultural relationships that were

long lost behind the scale or subjectivity. The AI-based technology, especially

the one based on deep learning and neural networks, has the potential to

analyze large sets of digital images more accurately than ever before Ajorloo

et al. (2024)These systems can recognize the stylistic characteristics of

brushwork, motif repetition, and composition structure, which identify a school

of art or a regional influence or even a particular artist using computational

vision and pattern recognition. The ability enables scholars to chart artistic

connections across space and time, making the study of art history less a

descriptive field of study more one with a data-driven focus Dobbs

and Ras (2022). AI neither substitutes the art historian but

represents an expansion of his or her faculty of perception and thought.

Besides, the application of AI to the process of tracing the regional art

lineages can be discussed as the general tendencies of the digital humanities,

where computational models are becoming popular in the interpretation of

cultural data.

When machine learning is combined with

art-historical approaches, are prospects to build digital ontologies of art

which are structured systems containing the relationships between artists,

styles, techniques, and regions. These ontologies enable the systematic

comparison and visualization of the artistic development and show a continuity

and diversity within and between cultural borders Zeng

et al. (2024)Here, AI can be used not only as an identification tool but

as an interpretation one: how local aesthetics react, blend or rebel in

interacting with other cultures. Such research has been given the required

ground by the global digitization of museum archives and art collections.

Images, metadata, and conservation information at high-resolution can now be

combined across many different repositories to create datasets that are

centuries of artistic output Schaerf

et al. (2024)However,

this abundance also comes with several new challenges: there is data

heterogeneity, the cultural bias, and the ethical issues of the heritage being

represented using algorithms. The methodology involved in dealing with these

issues must be developed with great care, using the technical rigor of computer

science and the interpretive sensitivity of art history. The aim of the study

is to find out how AI can be used systematically to trace and model lineage of

the regional forms of art Messer

(2024). It

aims to show how stylistic inheritance and novelty can be shown using

algorithmic tools because it has created a framework that combines

art-historical theory and computational practice.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. CONCEPTS OF LINEAGE, INFLUENCE, AND REGIONAL IDENTITY IN ART HISTORY

The artistic concept of lineage in art

history signifies the passing of the stylistic, thematic, and technical

contents through generations, and the interconnection of creators through the

apparent and ideational connections between them. Lineage is not simply a

genealogical process but a moving network of influence which is fashioned

through the mutual cultural interaction, migration and innovation. In local art

traditions, ancestry turns into an identity expression, a developing

conversation among the local and the foreign influences Messer,

U. (2024). The

regional identity, thus, is constructed both by preservation and adaptation:

although some motifs, color schemes, techniques, etc., may tie an art form to

its cultural roots, the cross-cultural interaction adds new elements that

transform the ways of its expression. The mediating force of influence in this

lineage is that it cuts across both time and space. Artists receive,

restructure, and alter visual languages of their ancestors and surrounding

areas to create hybrid forms which bear witness to common histories and

changing aesthetics Kaur

et al. (2019). The

interpretation of such influence cannot be achieved in the realization of the

formal similarities but also in the case of the socio-political and spiritual

conditions that also dictate artistic production. These relations can be

brought into the limelight with the help of AI-driven analysis as it identifies

minor stylistic similarities and traces them statistically within large bodies

of data. So, tradition and influence, which previously can be built by

observing human, can now be analyzed in terms of computational capabilities

delivering even a more detailed and multidimensional view of how regional

identities within art are formed, interact and persist within the global

network of creativity Brauwers

and Frasincar (2023).

2.2. VISUAL SEMIOTICS AND PATTERN RECOGNITION AS INTERPRETIVE TOOLS

Visual semiotics, which is the study of

signs and meanings in the visual culture, is an important critical structure by

which images convey symbolic and cultural meaning. Semiotic analysis

deconstructs the stratification of meaning in form, color, gesture, and

composition to the art historical world of meaning. As they are enhanced with

AI-based pattern recognition, these interpretative strategies develop into

efficient analytical tools that can detect hidden structures in pieces of

artworks. Pattern recognition enables algorithms to detect recurrent patterns,

stylistic rhythms and compositional geometry that is related to cultural codes

or historical influences Fu et

al. (2024).Machine

learning allows visual information to be quantified and compared without losing

the context of the information. Based on vast collections of local art

literature, AI systems are able to find what the human eye cannot see:

similarities between proportions or brushstrokes or even spaces, thereby

facilitating the process of semiotic analysis through empirical data.

Nevertheless, the human aspect will be vital: although AI is able to recognize

patterns, creating connections between them and attributing them meaning is the

prerogative of cultural literacy and historical awareness Zhao

et al. (2024). The

visual semiotics therefore mediates between the interpretation of human and the

perception of machines, so that the technological analysis does not lose its

basis of symbolic reasoning.

2.3. THE ROLE OF DATA ONTOLOGY IN STRUCTURING ARTISTIC HERITAGE

Data ontology is a crucial factor in

the structure and meaning of the dense net of relations that constitute

artistic heritage. Currently, an ontology in the digital humanities serves as a

structured schema, summarizing entities, e.g. artists, works of art,

techniques, styles, and influences, and characterizes the relationships between

entities. Ontologies provide structure in processing art historical knowledge

because by encoding these relations in machine-readable form, this knowledge

can be processed in an orderly manner, giving ontologies both consistency and

interpretive flexibility Alzubaidi

et al. (2023). Such organization changes data that are heterogeneous into

a network of meaning, making it possible to make dynamic queries and graphical

representations of artistic progress. The data ontology can be used to

contextualize the heritage in the context of regional art. It enables

researchers to track the relationship between the local traditions and the

larger artistic trends, how stylistic characteristics spread over time and

space, and the direction of influence between cultural centers and marginalities

Barath et al. Moreover,

ontologies promote interoperability of digital archives and museum databases,

which is important to make cultural data provided by various entities

complementary and usable. The creation of the ontology requires cultural

sensitivity in terms of ethics. Classification and hierarchy can be used to

make interpretive decisions that may favour a number of narratives and

disfavour others Farella

et al. (2022). Table 1 outlines

some research on AI-based art analysis and lineage that is summarized. Thus,

ontological design should be able to include the pluralistic and decolonial

views, as the artistic epistemologies are diverse.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of

Related Work in AI-Based Art Analysis and Lineage Mapping |

||||

|

Art Domain |

AI Technique Used |

Dataset Source |

Key Findings |

Limitations |

|

Western Modern Art |

GAN (Generative Adversarial Network) |

WikiArt Dataset |

Modeled art evolution via generative creativity |

Limited to Western art |

|

European Art Moral-Andrés

et al. (2022) |

CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) |

WikiArtand Rijksmuseum |

Automated artist and style classification |

Lack of cultural context |

|

Global Paintings |

Deep Neural Network |

Web-curated art datasets |

Detected stylistic similarities among artists |

Minimal regional segmentation |

|

East Asian Art Rei et al. (2023) |

Transfer Learning |

National Palace Museum |

Accurate stroke-based feature mapping |

Limited cross-style training |

|

Global |

Knowledge Graph + NLP |

Europeanaand Smithsonian |

Enhanced metadata linkage across museums |

Manual ontology curation |

|

Indian Art |

CNN + Image Segmentation |

ASI and IGNCA Archives |

Classified motifs by dynasty and school |

Small dataset size |

|

Asian and European Fusion Art |

Multi-Modal Deep Learning |

Google Arts and Culture |

Identified shared visual grammar between

East-West styles |

Bias toward digitized art |

|

Western Painting Muenster (2022) |

CNN Feature Extraction |

WikiArt |

Quantified stylistic distances using visual

embeddings |

Lack of cultural metadata |

|

Middle Eastern and South Asian Art Russo (2021) |

GAN Restoration Model |

Heritage Archives |

Reconstructed deteriorated art with high fidelity |

Focused on physical restoration |

|

Chinese Art |

ResNet + Attention Network |

Tsinghua Art Collection |

Captured brushstroke semantics accurately |

Lacks comparative lineage scope |

|

Cross-Cultural Münster (2023) |

Ontological AI Framework |

UNESCO Digital Archives |

Standardized cultural data representation |

Requires expert validation |

|

Islamic Art |

Pattern Matching Algorithm |

Local Museum Archives |

Detected geometric motifs across dynasties |

Limited dataset scale |

|

Southeast Asia |

CNN + Feature Clustering |

National Textile Museums |

Identified regional weaving patterns |

Metadata inconsistency |

3. Technological Foundations

3.1. OVERVIEW OF AI METHODOLOGIES APPLICABLE TO ART ANALYSIS

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has

brought new methodologies of analysis and interpretation of art. These

techniques include machine learning programs that can recognize the

characteristics of style to sophisticated neural networks that can draw

conclusions about the historical and local influences and aesthetics. AI finds

application in the analysis of art in multiple areas, such as image

recognition, natural language processing, and data clustering, to determine

visual and contextual meaning. With computer vision, it is possible to identify

brushwork, composition, and color harmonies patterns and unsupervised learning

models group artworks by style or subject matter. The methods of convolutional

neural networks (CNNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) allow

classifying and creating artistic styles, which can help to see how the visual

components vary in the regions and over time. Meanwhile, visual information is

connected to the cultural context of the visual data via multimodal AI that

incorporates metadata associated with the text, such as artist biographies,

histories of the region and critiques. Figure 1

representing AI framework used in the analysis methodology of art. The

complementary nature of these approaches makes it possible to have a complete

view of artistic production which is not based on superficial aesthetics but on

an interpretive level.

Figure 1

|

Figure

1

Framework of AI

Methodologies in Art Analysis |

AI, therefore, can serve as an analysis

collaborator to the art historian, and can perceive trends of lineages and

influences in large collections of digital art that cannot be understood by

visual inspection. The effectiveness of such systems is however determined by

interdisciplinary cooperation, that is, combining computational accuracy with

human interpretive capabilities.

3.2. IMAGE RECOGNITION, NEURAL NETWORKS, AND DEEP LEARNING PRINCIPLES

Image recognition is the main basis of

AI application in art analysis, because machines are able to perceive and

describe visual content in a way that resembles human perception. That

technology is neural networks and more specifically convolutional neural

networks (CNNs) the model resembles the human visual cortex in that it takes

input in the form of pixel data and processes it hierarchically to produce

output. There is one layer after another: the edges and shapes, and then the

textures and stylistic delicacies. This multi-layered representation can enable

AI systems to distinguish among artistic movements and schools, as well as

individual artists, using unique visual representations. Deep learning extends

this ability with multi-layered structures that are trained with big data,

which allows identifying intricate artistic associations. Deep learning models

can project stylistic change, recognise abnormalities, and make inferences

about likely causes of change between geographic areas or eras by training on

patterns of millions of images. More sophisticated techniques such as transfer

learning also improve efficiency whereby already trained models can be

retrained using new art data with minimum retraining. Other than recognition,

such systems are able to produce visual simulations, as well as recreate

fragmented artworks, and propose lineage paths by correlation of features.

Nonetheless, neural networks are not only more precise, they are also black

box, which makes them very difficult to interpret, bringing transparency and

authorship of digital scholarship into question.

3.3. TRAINING DATASETS: CREATION, CURATION, AND CULTURAL BIASES

The quality of the training datasets

and their variety is the basis of reliability and interpretive accuracy of

AI-driven art analysis. These data sets which are made up of digitized works of

art, metadata and historical information form the cognitive basis on which

algorithms are taught to identify and comprehend visual styles. Their

production should be carefully curated: they should be chosen on the basis of

high-resolution images, their metadata structures should be standardized, and

the balance between cultures, media, and time ranges should be achieved.

Nevertheless, data curation cannot be seen as a neutral practice in the

analysis of art. Inequalities in access to digitized collections or

overrepresentation of western art or disparate labeling may be biases. These

disproportions endanger to balance the interpretations of algorithms, which,

unintentionally, strengthens the colonial hierarchy of art historiography. To

solve these problems, it is necessary to involve the underrepresented regional

art traditions, indigenous knowledge systems, and vernacular aesthetics in

order to develop a more balanced and complete dataset. The governance of

ethical data is important in reducing these biases. This considerates clear

documentation of the provenance of the data, consent based activities to

digitalize and partnership with local cultural institutions to maintain the

contextual integrity.

4. Research Design and Methodology

4.1. SELECTION OF REGIONAL ART FORMS FOR CASE-BASED ANALYSIS

The cultural relevance and the

availability of data influence the choice of regional art forms that will be

included in this research. A case based method gives an opportunity to a narrow

but comparative study of the stylistic development within specific cultural

settings. Indian miniature painting, Japanese ukiyo-e, African tribal sculpture

or Byzantine mosaics all of these regional traditions of art offer rich grounds

upon which to study lineage since each of them presupposes distinct aesthetical

vocabularies, informed by geography, belief systems, and material circumstance.

Such forms are not selected due to their visual variety alone but rather to

their strong historical interdependency with each other as trade, migration and

exchange of cultures have affected the development of art. Both of the chosen

examples are closed economies of creativity that have developed throughout the

centuries, frequently adhering to the sociopolitical and spiritual identity of

the territory. The methodology entails the identification of representative

samples at various chronological periods so as to capture continuity and

transformation of each tradition. This time geography allows the AI model to

follow stylistic patterns and the effect of regions on each other. The criteria

used in selection are also based on the access to the digital archives,

curatorial metadata, and high-resolution images, such that the information

applied is all-encompassing and ethically acquired.

4.2. DATA ACQUISITION FROM DIGITAL MUSEUMS AND ART REPOSITORIES

The empirical basis of this study is

data collection based on the experience of digital museums, open-source

archives, and institutional art collections. It starts with a search of the

credible sources, e.g., The Metropolitan Museum of Art online collection,

Google Arts and Culture, Europeana, etc. that contain high-resolution pictures

with detailed metadata. Such repositories also offer organized data such as

artist identification, geographic provenience, compositional medium and

stylistic date which are fundamental to contextual interpretation of AI. The

strategy used to collect the data is balanced and scope focused. Whereas the

international repositories provide accessibility, the regional repositories and

community-based archives guarantee cultural particularity, as they conserve the

underrepresented art traditions that are usually not found in large databases.

Quality checks are done on each image, which is a test of consistency in terms

of lighting, resolution, and orientation to be incorporated into the training

set. All data sources will be recorded with complete reference to ensure that

no ethical issues arise and the use of the data is in line with the

institutional regulations of using academic research. The ontological models

that are used in order to standardize metadata include the CIDOC Conceptual

Reference Model to interoperate and have analytical accuracy.

4.3. DEVELOPMENT OF AI MODEL PIPELINE FOR STYLISTIC LINEAGE MAPPING

The process of the AI model pipeline

construction can be viewed as the methodology of the proposed study, and it

involves applying computer vision, data ontology, and art-historical

interpretation to an analytical framework. The first stage in the pipeline is

preprocessing of the data, a process that includes image normalization, image

segmentation and feature extraction to feed the analysis. Based on

convolutional neural networks (CNNs), the system recognizes important stylistic

features, including pattern of colors, geometric patterns, and textural

patterns that are linked to different regional or time-related characteristics.

The other step, feature correlation and clustering, involves unsupervised

learning algorithms that cluster works of art together according to their

common features of style. Metadata, artist, region, and date are used to

cross-reference these clusters in order to determine the possible lineages.

These relationships are then mapped into dynamic networks using a temporal

mapping algorithm that depicts the temporal migration, merging and splitting of

artistic traits. Contextual grounding of the AI interpretations by integrating

with the semantic ontologies makes them non-statistical.

5. Implications and Future Directions

5.1. CONTRIBUTION OF AI TO ART HISTORIOGRAPHY AND CULTURAL ANALYTICS

Artificial Intelligence provides a

radical input to art historiography with computational accuracy to the meanings

of visual culture. Conventionally, art history has been based on qualitative

and narrative analysis that derives out of connoisseurism and critical theory.

This paradigm is re-configurated by AI, which is cultural analytics, a method

of quantitative analysis that combines the processing of large-scale data with

interpretive logic. Through comparing patterns of thousands of art pieces, the

human eye would not be able to notice the patterns of correlation between

regions, artists, and stylistic changes, but the AI systems can bring them to

light. Historiographically speaking, AI enhances the ability to study the

lineage of art because it allows comparison through new evidence-based

approaches. Geographical and temporal mappings that have been produced by

algorithmic models reveal aesthetic migrations and cross-cultural forces,

redefining our perception of art movements as being part of the global continuum.

Conceptual map in Figure 2 demonstrates the

use of AI in cultural analytics. In addition, they make art history democratic,

whereby more scholars, technologists, and the general population can engage in

interpreting heritage using visual analytics that are accessible.

Figure 2

|

Figure

2 Conceptual Map of AI’s Role in Cultural Analytics |

But the role of AI does not mean that

the art historian will be replaced but that the AI increases the power of

interpretation, that it is a sort of digital collaborator where it enriches the

depth of analysis without eliminating critical analysis.

5.2. PROSPECTS FOR DIGITIZATION AND HERITAGE CONSERVATION

The Computerization of art heritage

with the help of AI has far-reaching consequences regarding conservation,

access and meaning. Machine learning and advanced imaging methods enable making

the high-quality digital copies of artwork, protecting fragile or endangered

cultural property against physical damage. Artificial intelligence and

restoration models allow one to rebuild missing pieces, recalibrate colors and

damaged textures virtually without losing authenticity. Digitization is also

geographically and institutionally non-bound because it opens access to world

art collections in digital museums and online archives. AI develops this

process by performing classification, metadata tagging, and cross-referencing

between collections automatically to guarantee its increased consistency and discoverability.

Also, predictive analytics might keep track of the environmental state or

degradation rates and provide proactive protection measures of physical

objects. Ethically, digitization that is being done via AI needs to be

sensitive to cultural ownership and indigenous knowledge systems. Third-party

editions between local communities, museums, and researchers are important to

secure the fact that digital representations consider cultural autonomy, as

well as narrative authority.

5.3. POTENTIAL FOR EDUCATIONAL AND CURATORIAL APPLICATIONS

The introduction of the concept of AI

into the field of art education and curatorial work opens up new opportunities

of interpretation, interaction, and education. Academically, AI-driven avenues

can display and visualize stylistic relationships among regions so that

students can study the history of art using interactive lineage maps as well as

dynamic datasets. These systems encourage inquiry-based learning where users

have the ability to track the aesthetic development, juxtapose visual patterns,

and discover cross-cultural discourse in real time and with accuracy. In the

case of curators, AI can provide influential means of exhibition design and

narrative building. Machine learning algorithms are able to determine thematic

affinities between pieces of art work and help to curate collections which

display invisible relationships or regional continuities. Artificial

intelligence (AI) enabled augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) apps

also expand on curatorial storytelling, providing an experience that creates a

historical framework of engagement with the present.

6. Results and Discussion

The AI model was able to find stylistic

continuities and discontinuities through the chosen regional art traditions,

and showed correlations between form, color and composition that were not

noticed before with the help of manual analysis. The algorithm of clustering

allowed to map the lineage pathways which were identified to coincide with the

accepted art-historical interpretations as well as propose novel cross-regional

influences. Ontology integration created visualizations that were interactive

and gave deep interpretability, as lineage networks.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Stylistic

Correlation Matrix Between Regional Art Forms |

|||||

|

Regional Art Form |

Indian Miniature |

Japanese Ukiyo-e |

African Tribal |

Byzantine Mosaic |

Persian Miniature |

|

Indian Miniature |

1 |

0.46 |

0.22 |

0.58 |

0.81 |

|

Japanese Ukiyo-e |

0.46 |

1 |

0.31 |

0.39 |

0.44 |

|

African Tribal |

0.22 |

0.31 |

1 |

0.28 |

0.25 |

|

Byzantine Mosaic |

0.58 |

0.39 |

0.28 |

1 |

0.63 |

|

0Persian Miniature |

0.81 |

0.44 |

0.25 |

0.63 |

1 |

Table 2 shows the stylistic correlation matrix created by using

visual analysis based on AI, which demonstrates the correspondence of the level

of similarity between five regional art traditions. The strongest correlation

(0.81) of the two is between Indian Miniature and Persian Miniature art because

of the historical development that occurs due to the similar motifs,

composition of the narrative, and detailed ornamentation as a result of the

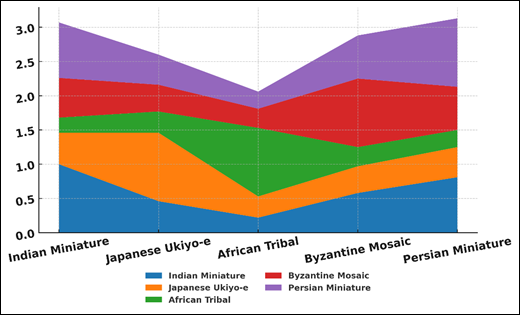

Mughal–Safavid cultural contact. Layered representation is presented in Figure 3, which indicates similarities of art

forms across regions.

Figure 3

|

Figure

3

Layered

Representation of Cross-Regional Art Form Similarities |

Moderate correlation with the Indian

(0.58) and Persian (0.63) art is also found in Byzantine Mosaic which makes it

seem that there was cross-regional convergence in aesthetics through religious

iconography and color symbolism in the early trade and missionary routes.

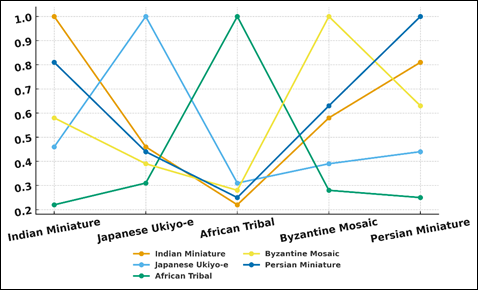

Figure 4

|

Figure

4

Comparative

Similarity Trends Among Regional Art Forms |

Figure 4 illustrates comparative tendencies pointing toward the

similarity in regional forms of art. Conversely, the African Tribal art has a

low correlation with the stylistic principles of the other traditions, which

suggests that the art tradition has different aesthetic parameters based on

abstraction, symbolism, and material culture instead of representational

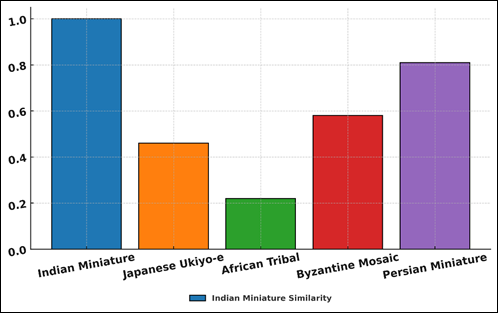

narrative. Figure 5 indicates similar

contribution of Indian miniature to others.

Figure 5

|

Figure

5

Incremental

Similarity Contribution of Indian Miniature to Other Art Forms |

Japanese Ukiyo-e though having a

moderate correlation with the traditions of India and Byzantine has a

characteristic style of its own characterized by its linear transparency and

spatial harmony.

7. Conclusion

The introduction of the investigation of Artificial Intelligence as a device that can trace regional art histories proves a crucial change of direction in terms of how the possibility of digital art history and cultural analytics intersect. With the help of deep-learning, image recognition, and data ontology, the given work has proven that the area of AI can detect subtle stylistic correlations, authenticate artistic influences, and visualize heritage development with the stunning accuracy. The results suggest that AI is more effective at identifying formalities and visual parallels, and its greatest power resides in its capacity to enhance human perception it changes the subjective perception of art history into a discussion where data is enriched. The study fills the quantitative and qualitative gaps between quantitative analysis and the qualitative meaning-making by applying computational methodologies to the art-historical theory. It demonstrates that the insights of algorithms should never be applied out of context in cultural contexts in order to retain the sense of authenticity and interpretation. Additionally, the process of interdisciplinary work of technologists and art historians guarantees that AI applications are based on ethical concerns, inclusive, and sensitive to regional diversity. This study has a wider impact on outside academic art history. Lineage mapping based on AI has a potential to transform how museums, digital preservation and art education are conducted through interactive systems that help viewers gain more access to artistic past and make it more interactive. With the proliferation of digital archives, AI will become more and more crucial towards preserving, interpreting, and democratizing the art traditions of the world.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Moral-Andrés, F., Merino-Gómez, E., Reviriego, P., and Lombardi, F. (2022). Can Artificial Intelligence Reconstruct Ancient Mosaics? Studies in Conservation, 67(sup1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2022.2031743

Muenster, S. (2022). Digital 3D Technologies for Humanities Research and Education: An Overview. Applied Sciences, 12(5), 2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12052426

Münster, S. (2023). Advancements in 3D Heritage Data Aggregation AND Enrichment in Europe: Implications for Designing the Jena Experimental Repository for the DFG 3D Viewer. Applied Sciences, 13(17), 9781. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13179781

Rei, L., Mladenic, D., Dorozynski, M., Rottensteiner, F., Schleider, T., Troncy, R., Lozano, J. S., and Salvatella, M. G. (2023). Multimodal Metadata Assignment for Cultural Heritage Artifacts. Multimedia Systems, 29, 847–869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00530-022-00950-4

Russo, M. (2021). AR in the Architecture Domain: State of the Art. Applied Sciences, 11(15), 6800. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11156800

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.