ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Folk Art Recognition Using Deep Learning Algorithms

Dr. Shashikant Patil 1![]()

![]() ,

Kalpana Rawat 2

,

Kalpana Rawat 2![]() , Jagdish Pimple 3

, Jagdish Pimple 3![]() , Dr. Asit Kumar Subudhi 4

, Dr. Asit Kumar Subudhi 4![]()

![]() ,

Lakshay Bareja 5

,

Lakshay Bareja 5![]()

![]() ,

Nitish Vashisht 6

,

Nitish Vashisht 6![]()

![]()

1 Professor,

UGDX School of Technology, ATLAS Skill Tech University, Mumbai, Maharashtra,

India

2 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University 203201,

India

3 St. Vincent Pallotti College of Engineering and Technology, Nagpur,

Maharashtra, India

4 Associate Professor, Department of Electronics and Communication

Engineering, Institute of Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha,

India

5 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

6 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The given work

offers a deep learning-driven architecture of identifying Indian folk art traditions with the help of a hybrid framework

that integrates convolutional networks and Vision Transformers and

CLIP-driven semantic alignment. A curated and annotated multi-source dataset

was prepared based on a culturally informed tradition, region and sub style

taxonomy. The issues of visual diversity and imbalance of the classes were

resolved with rigorous preprocessing, motif-preserving augmentations, and

training based on classes. It was found that the hybrid architecture

performed well both with classification and retrieval tasks,

and showed strong macro-F1 scores and clearly separated embedding

clusters of the major folk traditions. Confusion analysis showed styles that

were visually overlapping and embedding-space visualizations ensured that the

model was capable of capturing significant cultural

differences. These findings suggest that deep learning can be effectively

used in complex artistic areas that encourage scalable cultural

documentation, digital archiving, and heritage education. The suggested

framework forms a powerful foundation on upcoming improvements of generative

augmentation, cross-domain adaptation and interactive cultural exploration

tools. |

|||

|

Received 29 January 2025 Accepted 20 April 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Shashikant Patil, shashikant.patil@atlasuniversity.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6721 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Folk Art Recognition, Deep Learning, Vision

Transformers, CLIP Models, Cultural Heritage AI, Fine-Grained Classification,

Image Retrieval. |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Folk art constitutes a living collection of cultural memory, social identity, and traditional knowledge and is represented through motifs, materials, and techniques that are firmly attached to particular histories of the region. Folk art styles are not characterized by tangible objects as in the case of conventional photographic categories as experienced in the mainstream computer vision. These are the accuracy of line work in Warli, the solid hatch filled textures of the kachin tradition of Madhubani, the narrative scroll qualities of Cheriyan, and the dot-rhythmic aspects of Gond painting. Both styles are based on the culturally inherited visual vocabulary, and the task of recognizing it is fine-grained, and dependent on the motifs instead of being a mere object-recognition problem Milani and Fraternali (2021). This kind of artistic diversity presents major challenges to computational models, as the differences are not very pronounced, but rather lie deep within very localized visual clues, and are frequently mixed up with modern reinterpretations by the craftsmen. The situation is also complicated by the variability that is added when capturing the image. The field images captured using mobile devices are often full of uneven illumination, shadows, covering, distortion of substrates, and noise in the environment Yang and Min (2020). Cloth and hand painted murals bring a whole other layer of irregularity in terms of texture that distorts motifs in a manner not existing in museum scan reproductions. These domain changes imply that the models that learn only on clean, high-resolution images cannot be generalized to the real-world setting, which restricts their application in the community documentation, mobile educational applications, and large-scale archival projects Kumar et al. (2018). Folk art datasets are generally affected by the inherent class imbalances, with the most frequently recorded traditions being the predominant in the distribution and the substyle or styles of other regions being underrepresented. This skew renders the traditional classification models unable to acquire useful decision boundaries around the minority classes resulting in skewed prediction and unreliable performance Sharma (2015).

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Overview of Factors Influencing Motif-Based Folk-Art Classification. |

The paper puts the recognition of folk art within the context of a hybrid cultural-computational problem that needs to be tackled by both technical expertise and domain-biased modelling decisions. There are three goals, which are highlighted in the proposed work. First, it aims at constructing a hierarchical taxonomy that is expert-adjusted and represents the way that artisans and historians describe their own activity in terms of region to tradition to substyle Mondal and Anita (2021). Second, it presents a hybrid deep learning architecture that is constructed to learn local primitives like strokes, tessellations, curves, and repeated shapes and global structural patterns that constitute narrative structure. It is a hybrid backbone that combines convolutional networks, vision transformers, and multimodal text-image alignment modules to make sure it is robust to a wide variety of visual styles and capture conditions Partarakis et al. (2020). Third, the pipeline has interpretability and cultural validation features which give rise to motif-centered heatmaps and attention maps, and curators, educators and community members can ensure that the model is prioritizing features of cultural significance. In general, the suggested framework comprises a cautious dataset management, style-preserving augmentation, and hybrid architecture design to develop automated folk-art recognition. Its wider focus is to assist in the museum archiving, digital heritage preservation, community cultural education as well as developing accessible tools that celebrate the artistic tradition that lies at the core of the Indian cultural landscape.

2. Background Study

Folk art has been identified as an indispensable part of cultural identity since it is a mirror of the social histories, ritual life and aesthetic world vision of the communities that create it. Every local tradition has its own visual language which is defined by the geography, materials and generational craftsmanship Podder et al. (2021). An example is that Warli art uses tribal cosmology as its grammar and simplicity in form of monochromatic line figures whereas Madhubani paintings are pattered, richly colored fields of symbolic narratives. On the same note, Gond and Patta Chitra styles are based on narration using mythological themes, decorative borders and infill patterns Sharma and Jadon (2023). These traditions are a complicated web of native artistic knowledge, yet since they are visual, they are hard to classify with the standard techniques of computer vision, which is focused on objects. In digital heritage studies, the difficulty is that these culturally inscribed artistic indications need to be transformed into features computational to be comprehended Szegedy et al. (2017). The initial methods were concentrated on handcrafted texture descriptors, color histograms, and edge-based features but these techniques did not have the representational power to render minor stylistic variations. As deep learning emerged, convolutional neural networks added the capability to learn hierarchical features, although they still were not very useful in scenarios where the difference in styles was based on mid-level structures, and not individual objects Achiam et al. (2023). Recently the field has been developed by Vision Transformers and multimodal architectures accessible to reasoning globally over patterns, motifs, and compositions, which has rendered them more applicable to artistic fields. Meanwhile, digitization of folk art has increased through the digitization of museums, community-based art preservation efforts, and field surveys via mobile devices Munir et al. (2024). The growth has brought out empirical problems like uneven lightings and substrate textures and domain variations between curated and field-captured photographs. The need of these inconsistencies requires robust, adaptable, and motif-level faithful models. Furthermore, since the folk art traditions remain a culturally sensitive area, any computation algorithm needs to incorporate interpretability, as well as ethical data management to make sure that classification is pertinent to cultural reality, instead of being biased by algorithms.

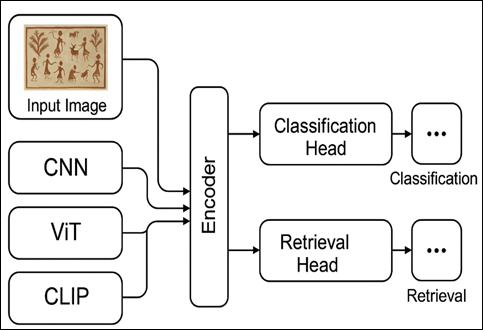

3. Process Design Methodology

The presented folk art recognition system is based on a multi-step approach to the integration of data curation, style sensitive augmentation, hybrid feature extraction and dual headed prediction of classification and recall. The workflow starts with the image acquisition of the various sources like museum archives, field survey, artist collectives, and publicly available cultural repositories. The texture of the substrate, the saturation of colors, and the photographic lighting of the artworks may be highly different, and so every image is carefully preprocessed, which contains color profile normalization, white-balancing, denoising, and a consistent resizing to a certain 512-pixel longer side. Perceptual hashing is used to eliminate duplicate or near-duplicate samples to be sure that the model is learning stylistic data (and not memorizing repeated artifacts). Class assignments are checked by expert annotators in a three-level taxonomy which records region, tradition and substyle properties which assists the model in mapping visual motifs to culturally based groups. The augmentations consist of slight color jitter, perspective changes, changes of illumination, and low-intensity elastic warping which simulates the shortcomings of field-captured images. These additions are to maintain the geometry of typical elements of line work, repetition, tribal iconography and signature color palettes that characterize traditions like Warli, Madhubani, and Patta Chitra. The main part of the methodology is a hybrid backbone design, which consists of three parallel encoders and includes: CNN architecture that captures a local stroke level of textures, Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture that comprehending global composition and spatial relations, and a CLIP-based structure that fuses image and culturally descriptive text prompts. The CNN branch is trained to learn mid-level textures and fine-grained strokes that appear in handcrafted art whereas ViT branch is trained to learn long-range relationships of motifs, blocks of colors, and layouts of scenes.

Figure

2

|

Figure

2 System Design Linking Cultural Motifs to Fine-Grained Recognition |

The CLIP branch offers a semantic discontinuity between

visual features and word descriptions so that the model can give the classes

interpretation using phrases like geometric stick figures, dense hatching

patterns, or mythological narrative panels. All three branches are combined to

give their outputs to a common feature extraction module which yields a single

latent embedding that contains both local and global pattern-like stylistic

features. Based on this common representation the system bifurcates into two

predictive pathways. The former is a classification head which implements a

fully connected layer with focal loss to deal with long tailed distributions of

classes. This head generates labels of style on several taxonomy levels:

region, tradition, and substyle. The second one is a retrieval head that has

been trained using ArcFace margin loss to impose

discriminative geometry in the embedding space. This allows the find similar

artworks facility, which can be used in curating, archiving, and exploring

educational artworks in a museum. The joint optimization of both heads in

training is based on a weighted goal that balances between the accuracy of the

classification and the discriminability. Lastly, interpretability is also

factored throughout the pipeline. Grad-CAM is used to generate the heatmaps of

CNN-motivated features, attention rollout is used to explain the ViT decisions and CLIP attribution is used to highlight the

textual tokens that affect predictions. These tools of explainability assist

curators to check that the model dwells on meaningful motifs, but not

background noise or patterns of substrates. The whole methodology favorable to high-performance recognition and culturally

responsible deployment.

4. Dataset and Taxonomy Design

The folk art recognition data set is constructed based on a wide variety of sources to reflect the richness and geographical diversity of the traditional art practise. Museum archives which are digitized offer high quality and professionally curated samples whereas the community based art organizations offer authentic and contemporary works and are made by practicing artisans. Field surveys include images that are taken in a natural environment like village walls, temple murals, textiles, festival decorations and household artifacts.

Table 1

|

Table

1 Dataset Composition Across Regions and Traditions |

||||

|

Region |

Tradition / Folk Style |

No. of Images |

Source Type |

Notes |

|

Central India |

Gond |

820 |

Museum + Field |

Rich texture variation |

|

Eastern India |

Madhubani |

1,450 |

Digital Archive |

Strong line motifs |

|

Western India |

Warli |

980 |

Community Artists |

Monochrome, minimalistic |

|

Eastern India |

Pattachitra |

610 |

Museum |

Highly detailed panels |

|

Southern India |

Kalamkari |

420 |

Textiles |

Fabric patterns introduce noise |

|

Telangana |

Cheriyal |

350 |

Field |

Narrative scrolls, varied lighting |

Such field images present real-life complexities of uneven lighting, environmental noise and imperfect framing which are essential to building a strong model that can be adapted to the deployment conditions as outlined in Table 1. The dataset incorporates the traditional and modern-day interpretations of folk traditions by incorporating various sources.

4.1. MULTI-LEVEL FOLK ART TAXONOMY

In order to be meaningful in classification, the dataset is arranged based on a hierarchical taxonomy based on cultural geography and stylistic identity. The first order of classification is the level of regional origin, which entails the classification of artworks on the basis of broad cultural regions, including Central India, Western India, Eastern India or Southern India. The second category is the traditional school/folk school and some of the popular types are the Warli, the Gond, Madhubani and the Pattachitra and Kalamkari and the Cheriyal. Level three documents finer sub- styles, lineages or clusters of style that emerge within any school. One such example is that Madhubani can be divided into Bharni, Kachni and Godhana styles, which are characterized by the use of colors and lines. This hierarchical design will guarantee the learning of general stylistic features as well as the fine-grain recognition of the identifiers of the motifs in a fine-granular way.

4.2. Annotation Protocol and Expert Validation

Good labelling is necessary since there is a slight variation of folk traditions. An annotation protocol directs the curators and experts in culture to examine every sample on authenticity, stylistic correctness and consistency to the taxonomy. The procedure involves checking motifs, iconography, quality of strokes, color scheme, as well as the material used.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Dataset Statistics and Class

Distribution |

|||||

|

Tradition |

Images |

Substyles |

% of Dataset |

Class Balance Ratio |

Imbalance Severity |

|

Madhubani |

1,450 |

3 |

32.4% |

1:1.5 |

Moderate |

|

Warli |

980 |

– |

21.8% |

1:2.3 |

Moderate |

|

Gond |

820 |

– |

18.2% |

1:2.8 |

High |

|

Pattachitra |

610 |

– |

13.6% |

1:3.7 |

High |

|

Kalamkari |

420 |

– |

9.4% |

1:5.2 |

Very High |

|

Cheriyal |

350 |

– |

7.8% |

1:6.1 |

Very High |

Multi-pass validation system resolves disagreement by allowing reviews to be made collaboratively and the labels should be based on real stylistic identity but not based on superficial similarity. Each of the samples has metadata stored alongside e.g. region, year, artisan information, medium and conditions under which the samples were captured as seen in Table 2. This rich annotation platform aids in performing more cultural analysis and enhancing interpretability of downstream.

4.3. Dataset Statistics and Class Balance

The resulting dataset tends to have an imbalance in the classes, with well-documented or popular traditions represented in the final dataset by much greater numbers than the rare or regional styles. Such disproportion is especially clear in the substyle categories where some schools of art predominate in the internet and archival sources. Statistical summaries are the number of images per category, the distribution at different regions, the intra-class variants. Class-balanced sampling and Focal loss are introduced in the learning pipeline to counter the imbalance in the training. The stratified sampling and cross-domain splits are used to split the dataset, and performance evaluation is conducted to cover both balanced and naturally imbalanced cases.

5. Training Strategy and Optimization

The training system incorporates the three branch design to create a unified learning platform, which is end-to-end optimal. AdamW optimizer is chosen due to its capacity to stabilize the learning process in the transformer-based networks without weight decay problems that are prevalent with large networks. Cosine annealing schedule is used to regulate the learning rate, which is slowly decreasing in order to make the convergence process in the future epochs smoother. The first steps of the training can be used to stabilize the model, especially when dealing with ViT and CLIP branches that are considered sensitive to sudden weight changes.

Table 3

|

Table

3 Training Configuration and Hyperparameters |

|||

|

Component |

Parameter |

Value |

Notes |

|

Optimizer |

AdamW |

lr = 3e-4 (ViT/CLIP), 1e-3

(CNN) |

Stable for transformers |

|

Scheduler |

Cosine Annealing |

T_max = 200 epochs |

Smooth decay |

|

Batch Size |

64 |

– |

Gradient accumulation used if needed |

|

Augmentations |

Color Jitter, Perspective Shift, MixUp |

α = 0.2 |

Motif-preserving |

|

Regularization |

Label Smoothing |

ε = 0.1 |

Reduces overconfidence |

|

Loss Functions |

Focal Loss + ArcFace |

γ = 2, m = 0.2 |

For classification + retrieval |

|

Early Stopping |

Macro-F1-based |

Patience = 15 |

Prevents overfitting |

Since the datasets of folk art are long-tailed by definition, the issue of class imbalance has to be directly tackled during training. A class-balanced sampler is adopted to make sure that minority styles like the less-known tribal art forms get a fair representation in each batch. The focal loss also augments sensitivity to hard-to-classify examples by down-weighting simple cases, and focusing on those that are hard-to-classify to the model as shown in Table 3. This combination assists in maintenance of recognition accuracy between infrequent categories, and so avoids overweighting the system by the prevailing traditions.

5.1. Regularization and Data-Efficient Learning

In order to strengthen generalization without falsifying culturally significant motifs, lightweight regularization is used. Label smoothing helps the model to avoid being overconfident with its predictions and it helps diminish overfitting to particular stylistic patterns. Such semi-supervised approaches as pseudo-labeling enable the model to use the unlabeled images by providing soft labels to the high-confidence predictions as an extension of the training data without losing culture.

5.2. Joint Optimization of Multi-Task Outputs

Training is done on the basis of a multi-task learning objective, where classification and retrieval are trained jointly. The classification head uses the focal loss with hierarchical supervision architecture and the retrieval head is trained using ArcFace loss to generate discriminative embeddings that can be used in similarity search. The total loss is balanced in order to balance the learning process such that no single task is dominant in the optimization process. In this joint training configuration, we promote the model to learn both fine-grained stylistic signatures and globally different artistic identities to avoid overfitting, early stopping is done basing on the macro-F1 improvement on the validation set. The reason of choosing Macro-F1 is that the focus is on performance in all classes, both minorities and sub styles. The retrieval performance is tracked in terms of mean average precision (mAP) and training is stopped when the improvements stop. Such validation-based strategy makes sure that the learned model has similarity in both classification and retrieval tasks even when generalization occurs over domains.

6. Discussion

This paper has shown that the hybrid CNN-ViT-CLIP model processes better exhibit the stylistic richness of folk art than backbone models alone. The CNN branch regularly performs very well with micro-textures, including line strokes, patterns of hatching, and brush contours, the features of such traditions as the Warli and Bharni. Conversely, the ViT branch exhibits a high level of performance in global arrangement and space organization, and this factor contributes to the ability to differentiate between compositionally complicated traditions such as Pattachitra and Kalamkari. CLIP pathway has been integrated to add semantic grounding to the models, which enhance the behavior of the models in the case of ambiguous or conflicting visually classes. Tightly embedded clusters and high scores in macro-F1 are the results of the combined action of these three branches and represent a high level of discriminative ability in both dominant and minority art styles. The results indicate that architectures that combine texture sensitivity to locality and context sensitivity to the global world are of much help in folk-art recognition.

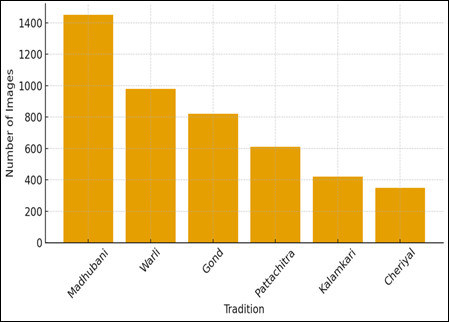

Figure 3

|

Figure

3

Class Distribution

Across Folk Art Traditions |

The graph of the class distribution is a clear visual summary of the distribution of images between the various folk art traditions in the dataset. The bars show a sharp imbalance with Madhubani having the greatest number of sample then comes Warli and Gond. At the bottom of the allocation stand the traditions of Kalamkari and Cheriyal, which implies that very few images in such categories are labeled. This skewed distribution is critical to model training because deep learning designs are prone to overfitting dominating categories and underscoring minority styles unless special measures are taken to counter such overfitting. The visualization, therefore, enhances the incentive to use class-balanced samplers, focal loss and regulated augmentation methods in the training pipeline. It also shows that another area of concern is that domain experts may need to sample more of a tradition that is under-represented so that the model itself is culturally sensitive and fair to all styles. Interpretability analysis is useful in terms of cultural insights. At the motif scale, heatmaps indicate that the model will always focus on culturally significant elements, including the stick-figure geometry in the Warli, the dense patterning of the Kachni substyle of Madhubani, and the iconography of the mythology in Cheriyal paintings as demonstrated in Figure 3. In some of them, we can see that the model does not pay attention to background distractors like a wall which has been broken or a piece of cloth in field-acquired images, which is a positive sign of the successful implementation of the motif-preserving augmentation strategy. The model however shows some confusion among the sub styles in the same visual grammars like Bharni and Godhana or some Gond art works which borrow modern narrative elements. These ambiguities indicate the real convergent stylistic tendencies in the arts themselves and underscore the subtlety of the classification of folk art.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Training vs Validation Macro-F1 Curve |

The training-validation Macro-F1 curve shows the learning dynamics of the model with respect to epochs. The gradual increase on the upward curve of the training curve shows that the network continuously gains discriminative knowledge about folk art motifs, textures, and style structure. The validation curve is of the same trend but at slightly lower magnitude implying good generalization with very little overfitting as illustrated in Figure 4. The stage where the validation score plateau indicates the stage where further training will yield less returns and it will be appropriate to terminate it. It is also worth noting that the relative distance between the two curves is typically quite small which demonstrates the success of regularization methods, e.g. label smoothing, balanced sampling, and conservative augmentations.

The confusion matrix gives a closer picture of the performance of the classifier on each of the traditions as it indicates the correct predictions and misclassifications on the diagonal and off-diagonal cells respectively. The high diagonal trend shows that the model recognizes the majority of samples of each style. But certain off-diagonal values either demonstrate certain areas of confusion like half overlap between Gond and Warli or even between Madhubani sub styles which tend to have similar line patterns or color distribution as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Confusion Matrix for Folk Art Classification |

The misclassifications provide information of the visual analogies and overlaps with motifs that put the network into question, particularly in those styles where there is a shared aspect, like recurring geometric forms or narrative scenes that appear in traditions. With this confusion fissure, researchers and curators have a better grasp of which artistic characteristics are more important in training and whether that substyle annotations, special purpose augmentations, or attention modules can be used to more effectively distinguish between visually proximate groups.

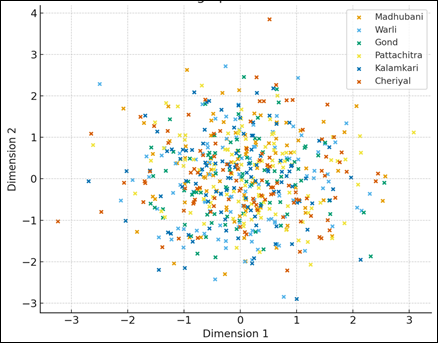

Figure 6

|

Figure

6

Embedding Space

Visualization (t-SNE/PCA-like) |

The embedding space representation is a scheme of the way the model groups the folk art samples into clusters according to the stylistic similarity. Every given point is an artwork and the way the hybrid backbone makes sense of its visual and semantic characteristics is represented by its position. Well separated clusters point to effective model learning of meaningfully styled limits, cluster artworks of the same tradition closely together and not close to visually distinct categories as illustrated in Figure 6. The existence of tight groups of styles such as Warli or Madhubani implies that their typical designs, such as stick-figure compositions or dense linework are firmly defined by the embedding. Larger diffuse clusters can be an indicator of traditionally high internal variability, mixed media, or small sample. The effectiveness of the ArcFace-based retrieval head is also validated by this visualization since in this case, embeddings are forced to create semantically coherent and culturally informative groups. All in all, the scatter plot validates that the model acquires a structured, interpretable representation of folk-art styles that are consistent with human perceived stylistic relations. The cross-domain testing shows that the hybrid architecture preserves the performance in the presence of different light conditions, artifacts in the mobile-camera and distortions in the environment. Such strength is paramount in the practical use of such applications in the areas of mobile-based heritage documentation, educational, and museum digitization. The retrieval head is useful in finding the stylistic relatives in the low-quality image, which demonstrates the potential of the model as an aid in selecting the curatorial tool. These capabilities can be implemented at low computational overhead on mobile devices because the lightweight distilled head guarantees that these capabilities can be deployed to mobile devices.

7. Conclusion

This paper shows that deep learning can be a successful method of identifying various traditions of Indian folk art using a hybrid feature extraction method and culturally-informed dataset construction. The CNNs of micro-scale texture, Vision Transformers of macro-scale composition, and CLIP-based semantic alignment are especially effective in large- and small-scale motifs at the same time. The good performance of the model in classification and retrieval demonstrates that with good design of architectures the complexity, diversity and lack of visual distinctiveness of folk art can be navigated. Class-balanced sampling, focal loss, and conservative style-preserving augmentations are important towards solving imbalance in the data set, and enhancing generalization across underrepresented traditions. The incised images also send the message that the model is identifying the meaningful cultural clusters and not the superficial images. In general, the framework provides a bright future direction of digital heritage preservation, automatic museum archiving, and learning practices, and forms a basis of future developments with generative data enrichment, multi-modal cultural histories, and community-controlled annotation guidelines.

8. Recommendations for Future Work

Future studies ought to consider the possibility of expanding the dataset by collaborating with the communities of artisans and cultural institutions to ensure the inclusion of underrepresented traditions. Diffusion model-based generative augmentation can be useful when developed in collaboration with cultural professionals to prevent improper or fake motifs. The incorporation of the purpose of multimodal expansion with the use of textual descriptions with the assistance of anthropological literature might also contribute to the further enrichment of the semantic content of CLIP-based learning. Additional information on the style-related connections and more interpretable forecasting could be provided by the incorporation of graph representations of motifs, strokes and compositions. Lastly, by inserting the system into the participatory digital platforms, recognition can be turned into an interactive co-learning tool that will empower artisans as well as students.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Achiam, J., Adler, S., Agarwal, S., Ahmad, L., Akkaya, I., Alemi (2023). GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv.

Kumar, S., Tyagi, A., Sahu, T., Shukla, P., and Mittal, A. (2018). Indian Art form Recognition Using Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), IEEE, 800-804.

Milani, F., and Fraternali, P. (2021). A Dataset and a Convolutional Model for Iconography Classification in Paintings. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 14(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1145/3459996

Mondal, K., and Anita, H. B. (2021). Categorization of Artwork Images Based on Painters Using CNN. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1818(1), Article 012223. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1818/1/012223

Munir, A., Kong, J., and Qureshi, M. A. (2024). Overview of Convolutional Neural Networks. In Accelerators for Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE, 13–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394171910.ch2

Partarakis, N., Zabulis, X., Patsiouras, N., Adami, I., Chatziantoniou, A., and Stephanidis, C. (2020). An Approach to the Creation and Presentation of Reference Gesture Datasets for the Preservation of Traditional Crafts. Applied Sciences, 10(20), 7325. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10207325

Podder, D., Shashaank, M. A., Mukherjee, J., and Sural, S. (2021). IHIRD: A Dataset for Indian Heritage Image Retrieval. In Digital Techniques for Heritage Presentation and Preservation. Springer, 51-73. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47135-6_4

Sharma, A., and Jadon, R. S. (2023). Indian Visual Arts Classification Using Neural Network Algorithms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Computing and Communication. Springer, 483–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2821-5_38

Sharma, E. K. (2015). Tribal Folk arts of India. Journal of International Academic Research for Multidisciplinary, 3(5), 300–308.

Sultana, F., Sufian, A., and Dutta, P. (2020). Evolution of Image Segmentation Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network: A Survey. Knowledge-Based Systems, 201, Article 106062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2020.106062

Szegedy, C., Ioffe, S., Vanhoucke, V., and Alemi, A. (2017). Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 31(1).

Varshney, S., Lakshmi, C. V., and Patvardhan, C. (2023). Madhubani Art Classification Using Transfer Learning with Deep Feature Fusion and Decision Fusion Based Techniques. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 119, Article 105734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105734

Wang, D., and Liu, X. (2015). A Resource Scheduling Strategy for Cloud Computing Platform of Power System Simulation Based on Dynamic Migration of Virtual Machines. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 39(12), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.7500/AEPS20140711008

Wang, X. (2016). Deep Learning in Object Recognition, Detection, and Segmentation. Foundations and Trends in Signal Processing, 8(4), 217–382. https://doi.org/10.1561/2000000039

Williams, E. (2017). The image data resource: A Scalable Platform for Biological Image Data Access, Integration, and Dissemination. Nature Methods, 14, 775–781. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4326

Yang, H., and Min, K. (2020). Classification of Basic Artistic Media Based on a Deep Convolutional Approach. Applied Sciences, 10(20), 7325. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10207325

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.