ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Predictive Algorithms for Structural Integrity in Sculptures

Dr. Pragati Pandit 1![]() , Damanjeet Aulakh 2

, Damanjeet Aulakh 2![]()

![]() , Dr. S Nithya 3

, Dr. S Nithya 3![]()

![]() ,

Sudhanshu Dev 4

,

Sudhanshu Dev 4![]()

![]() ,

Neha 5

,

Neha 5![]() , Dr. Hradayesh Kumar 6

, Dr. Hradayesh Kumar 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Information Technology, Jawahar Education Society's

Institute of Technology, Management and Research, Nashik, India

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

4 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

5 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International

University 203201, India

6 Assistant Professor Department of Arts, Mangalayatan University,

Aligarh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

In

computational modeling has provided avenues to evaluate and maintain the

structural integrity of sculptures, especially those that are exposed to

environmental factors or aging materials, or complicated distributions of

loads. Finite-element analysis, machine learning, and sensor-based data

collection together in predictive algorithms provide a proactive approach of

determining the risk of failure before it can be seen to be deteriorating.

These algorithms create probabilistic models and simulate stress propagation,

micro-fracture development and deformation at different conditions by

combining high-resolution 3D scans with material performance data of the

past. The ability to predict stability of the sculptures over a long period

of time, without any invasive processes, enables the conservators, engineers,

and artists to make the sculptures safer and more accurately preserved. The

use of predictive algorithms is not restricted to the field of diagnostics

but can also be used in decision-making during restoration and preventative

maintenance. The adaptive models are fed by real-time monitoring systems

which have accelerators, strain gauge, and

environmental sensors which continuously feed the data into this adaptive

model, which in turn improves its predictions with time. Anomaly detection

and regression-based forecasting are methods of machine-learning that can

subsequently categorize high-risk areas and predict schedules of possible

structural failure. This information-driven modeling and conservation practice

synergy does not only reduce the cost of restoration, but

also aids to keep artistic integrity of sculptures low as well by minimizing

cases of unwarranted interventions. Due to the development of predictive

algorithms, their great potentials lie in the fact

that sculpture conservation can be made a more precise, efficient, and

scientifically based discipline. |

|||

|

Received 27 January 2025 Accepted 17 April 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Pragati Pandit, drpragatipandit@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6715 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Predictive Algorithms, Structural Integrity,

Sculpture Conservation, Finite-Element Analysis, Machine Learning, Material

Degradation Modeling |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Sculpture

conservation has been a fragile and interdisciplinary practice, and it needs an

interpretation of artistic intentions, material behavior, and environmental

forces that determine long-lasting stability. The inherent vulnerability of

sculptures to structural deterioration due to weathering, stress due to

mechanical forces, pollution, biological growth, and fatigue of inner material,

make sculptures, whether implemented of stone, casted in metal, modeled in clay

or made of modern composite materials, prone to deterioration by structural

factors Aziz et al. (2025).

Those conventional technique of conservation are more based on visual

observation, hand examination and periodic condition evaluation, which, still

useful, tend to fail in detecting subtle or internal damage until it is in a

critical phase. These responsive methods restrict the conservation of the

conservators to act in a strategic manner, often leading to expensive

restorations or permanent losses Jayasinghe et al. (2025).

To these challenges, the predictive modeling has been introduced as some kind

of revolution in preservation of art. The accuracy of predictive algorithms,

especially those that integrate machine learning, predictive technology, and

real-time sensing technologies, is unprecedented to predict the vulnerability

of structures before they actually occur physically Yang and Huang (2025).

These models can be used to proactively, data-driven address sustainability of

sculpture by analyzing complex stress distributions, simulating the crack

propagation, and adding environmental and historical data to sculpture

conservation and improve safety and conservation planning. Nevertheless, the

conventional forms of assessment remain predominant, as access to digital

infrastructure, lack of technical training of conservators, and apprehension

about the intrusiveness or cost-effectiveness of monitoring technologies still

mitigate the potential of other technologies Latif et al. (2022).

The proposed research will fill this gap by describing a unified paradigm of

predictive algorithm development that is highly specific to structural

integrity assessment of sculptures. The research is centered on three

fundamental aims: enhancing the accuracy of the forecasting mechanical and

environmental failure modes; creating the workflows that combine the 3D

scanning, sensor data, and the material behavior in the past; and assessing the

performance of the algorithms using the case studies of various materials and

environmental conditions. Moreover, the study aims at providing the principles

of the working implementation so that the predictive modeling instrument would

be non-invasion, accessible, and ethically in line with conservation

principles. Offering an introduction to modern predictive algorithm methods

such as FEA-based simulation methods, unsupervised and supervised machine

learning methods and hybrid systems that adjust on-the-fly via sensor feedback

this paper highlights the sheer importance of computational methods when

protecting the heritage of sculptures Rashidi Nasab and Elzarka (2023).

With the cultural sector becoming more and more open to the digital

technologies, predictive algorithms can be seen as the future of conservation

as it becomes less of a reactive practice and more of a scientifically

grounded, proactive practice.

2. Literature Review

Traditional

methods of structural analysis of art objects have always been based on

qualitative observation, material knowledge, and physical investigation, and

the conservators have used empirical knowledge to diagnose the object,

determine patterns of stress distribution, and prescribe restoration strategies

Rashidi Nasab and Elzarka (2023).

The early conservation practices did not use standardized tools of analysis, so

their evaluations were usually subjective, extremely variable, and lacked

predictive power, particularly when applied to sculptures with complicated

internal geometries or internal defects of structure Gao and Elzarka (2021).

The introduction of scientific methodologies into the conservation sector saw

the scholars starting to use engineering-oriented methods of analysis in the

conservation field, and quantitative analysis of the structural system became a

fundamental transition to a qualitative assessment of the conservation problem.

Among them, one of the most powerful methods to calculate stress distribution,

load responses, and deformation and fracture behavior of cultural heritage

artifacts was the so-called finite-element analysis (FEA) Hu et al. (2023).

FEA was demonstrated to be useful in conservation of sculptures and other

objects of interest to conservators by studies that used FEA to determine the

mechanical stability of stone statues, bronze casts, wooden carvings, and

modern installations, and provided conservators with a more insight into the

effects of long-term environmental influences on structural integrity (humidity

changes, thermal expansion, wind load, vibration, etc.). Although the FEA has

its advantages, it needs specific material data and finer geometries, which may

be hard to get on old or heterogeneous objects, and scientists have sought

alternative computational methods to FEA.

Over the past few

years, machine learning has diversified the scope of tools of analysis that can

be used in material science and structural monitoring to allow automatic

pattern recognition, anomaly detection, and predictive modeling using past data

and sensor data streams Siahpour et al. (2022).

The support vector machines, neural networks, and clustering techniques are

machine learning algorithms that have been effectively utilized to forecast the

crack propagation, identify the early signs of corrosion, identify the patterns

of deterioration, and determine the material fatigue in the field of

engineering and adaptation to the conservation domain is increasing Zhao et al. (2024).

These methods are used to address certain limitations of deterministic models

since they can learn incomplete or uncertain data hence are especially helpful

in artworks with material properties which change with age, craftsmanship, and

environmental exposure Ao et al. (2025).

In line with machine learning innovations, sensor-based monitoring systems have

been on the rise as viable tools to conduct real-time structural evaluation.

Strain gauges, RFID-based stress sensors, accelerometers, fiber optic sensors,

and environmental temperature, humidity, and air quality modules are some of

the technologies that give continuous data that enable conservators to identify

emerging risk factors and confirm the simulations models Esteghamati and Flint (2021).

Sculpture conservation Sculpture conservation has been applied to monitor

micro-cracks, stress caused by vibration, internal moisture migration, and

surface displacement, and has been highly successful in both indoor museums and

outdoor heritage environments Ko et al. (2021).

Sensors networks combined with machine learning and FEA can also be utilized to

enable the hybrid predictive frameworks, which change with time to enhance the

accuracy and reliability of structural predictions Abdelmalek-Lee and Burton (2023).

Taken together, the current literature has shown considerable improvements in

the field of computational conservation, but there are still issues with

implementation cost, interoperability of data and interdisciplinary expertise

is required. With the further development of research, the intersection of

engineering simulation, artificial intelligence, and sensor technology is an

attractive trend to create powerful predictive systems that will be able to

provide preservation of sculptural artworks to future generations Jin et al. (2023).

Table

1

|

Table

1 Related Work

Summary Table |

|||||

|

Study / Approach |

Focus Area |

Methodology Used |

Materials / Sculptures Analyzed |

Key Findings |

Limitations |

|

Early Visual Inspection Methods |

Historical approaches |

Manual observation & documentation |

Stone, bronze, wood |

Effective for detecting visible damage |

Cannot detect internal weaknesses |

|

Traditional Mechanical Testing |

Historical approaches |

Physical probing, stress tests |

Aged stone sculptures |

Provided baseline understanding of material fatigue |

Invasive and potentially damaging |

|

Early FEA in Conservation |

FEA applications |

Basic finite-element modeling |

Marble and limestone statues |

Improved understanding of stress concentrations |

Required simplified geometries |

|

Advanced FEA for Complex Forms |

FEA applications |

High-resolution FEA simulations |

Multi-material installations |

Accurately predicted deformation and fracture zones |

High computational cost |

|

Environmental FEA Studies |

FEA applications |

Coupled thermal–mechanical modeling |

Outdoor stone monuments |

Showed strong influence of humidity & temperature cycling |

Relies heavily on precise material data |

|

ML for Degradation Classification |

Machine learning |

Classification & clustering models |

Corroded bronze surfaces |

Automated detection of deterioration patterns |

Requires large, labeled datasets |

|

ML-Based Crack Prediction |

Machine learning |

Neural networks & SVM |

Ceramic and stone artifacts |

Improved predictive accuracy for crack growth |

Black-box model interpretability issues |

|

ML for Material Fatigue Analysis |

Machine learning |

Regression-based fatigue models |

Metal and composite sculptures |

Useful for long-term failure estimation |

Sensitive to data noise |

|

Basic Sensor Monitoring Systems |

Sensor-based monitoring |

Strain gauges & humidity sensors |

Indoor museum sculptures |

Detected early micro-fractures |

Limited to point-based measurements |

|

Wireless Monitoring Networks |

Sensor-based monitoring |

Wireless IoT sensor arrays |

Outdoor installations |

Enabled real-time, remote monitoring |

Power and weather-related limitations |

|

Fiber Optic Sensor Systems |

Sensor-based monitoring |

FBG (Fiber Bragg Grating) sensors |

Large stone monuments |

High precision for strain & vibration |

High installation cost |

|

Hybrid Systems (FEA + ML + Sensors) |

Integrated approaches |

Combined simulations & data-driven models |

Multi-material heritage sculptures |

Most accurate prediction framework |

Requires interdisciplinary expertise |

3. Methodology

3.1. DATA ACQUISITION

3.1.1. 3D Scanning Techniques

The basis of the

development of predictive models with integrity assessment of sculptures is the

scanning in 3D. Laser scanning involves high precision LiDAR beams to scan the

geometry of the sculpture in dense point clouds with accuracy down to sub-millimeters.

This method is particularly useful to record complicated surface data,

complicated carvings, and uneven shapes that affect the distribution of stress.

Laser scanners can also be acquired at high rates and

this makes them suitable in the indoor and the outdoor environment with minimum

physical contacts. On the other hand, photogrammetry is based on the

acquisition of high-resolution images in different angles and processing them

with computer vision algorithms to create a three-dimensional representation of

the sculpture. Photogrammetry is flexible, less expensive and highly movable

thus suitable to remote location or whereby the conventional scanning devices

cannot be moved to. Whereas laser scanning is more geometrically accurate,

photogrammetry is better at textural fineness, color gradient, and surface

damage, and material heterogeneity. All these techniques form a rich digital

twin of the sculpture, which is necessary to make structural simulations

reliable and predictive modeling.

3.1.2. Material Characterization and Historical Degradation Data

Characterization

of materials is also important in developing the right predictive algorithms

because sculptures are usually made of heterogeneous materials which change

with time. This step implies determining the main composition of the sculpture,

i. e. stone, bronze, marble, wood, or composite materials, and examining its

mechanical, thermal and chemical characteristics. Micro-XRF, ultrasound

testing, and micro-indentation are some of the techniques used to measure

density, porosity, elasticity, hardness, and internal flaws. The parameters are

directly into simulation models so that predicted responses to stress are

realistic of material behaviour in the real world. Besides the current

characterization, historical degradation data will give an understanding of the

deterioration trends over a long period of time. The historical and past

restorations, climatic records, and photographic documentation of the sculpture

indicate how it reacted to aging, exposure to the environment, and the

mechanical loads over the decades. This kind of data increases the predictive

accuracy of such data by enabling algorithms to learn trends of deterioration

as opposed to using only short term data. The

influence of previous environmental conditions like freeze-thaw or exposure to

pollution or a seismic event could also be captured with historical data and

this could have created hidden structural weaknesses. Material analysis can be

utilized together with historical degradation datasets to provide a robust

model calibration that can provide predictive algorithms with high-precision

crack propagation, deformation and material fatigue. This is a holistic

solution so that the modeling framework only reflects not the current state of

the structure but the dynamic ageing process of the sculpture.

3.1.3. Environmental and Mechanical Load

Data Collection

Environmental and

mechanical loading information is necessary to know the external forces which

cause structural degradation. Parameters of environmental data are temperature

changes, humidity cycles, solar radiations, precipitation, and wind pressures which

determine diffusion of moisture, thermal expansion and surface erosion.

Mechanical load data, in its turn, records vibrations, constant loads, human

interaction dynamic forces and installation-induced stresses. Accelerators,

hydro sensors, thermocouples, and load sensors can be used to monitor

continuously, which is a valuable time-series data to be used in predictions.

These inputs are used to test the simulated stress conditions of the real world

and validate long-term predictive algorithms of the structural integrity.

3.2. ALGORITHMIC FRAMEWORK

3.2.1. fFINITE-ELEMENT MODELING

PROCEDURES

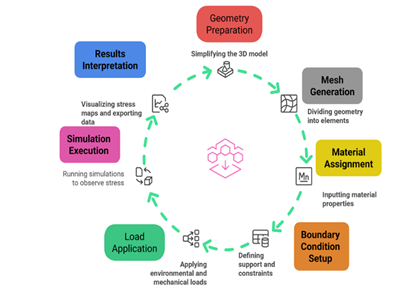

1)

Geometry Preparation: Import of the

3D-scanned model, and simplification of it to eliminate noise and unwarranted

detail.

2)

Mesh Generation: Subdivision of the geometry into small finite elements (tetrahedral or

hexahedral), which is highly mesh-dense in stress prone areas.

3)

Material

Assignment: Consenting characterized material characteristics including the Youngs

modulus, the Poisson ratio and density.

4)

Boundary Condition

Set-up: The support points, fixed constraints, and free movement areas.

5)

Load Application - Subjecting environmental and mechanical load environments, such as

temperature change, vibration and gravity.

6)

Simulation Run: Static, Dynamic and Thermal stress Simulations are run to monitor

deformation, strain distribution and possible areas of failure.

7)

Results Interpretation Visualization of stress maps,

risk region identification and export data to integrate with machine learning

models.

Figure

1

|

Figure 1 Finite-Element Modeling Cycle |

The Figure 1 shows the work flow of finite-element modeling

sculpture integrity analysis. It starts with the preparation of geometry then

mesh generation and assigning the material. Limit conditions and loads are

introduced and the simulation is simulated. The cycle is completed with the

help of stress visualization and data export. The color scheme and symbols make

it easier to read and comprehend, and difficult stages of the simulation become

understandable to both researchers and conservators.

3.2.2. Machine Learning Models

Machine learning

improves predictive accuracy by distilling patterns of data which are perhaps

not entirely represented by the traditional models.

Linear regression,

random forest regression and gradient boosting predictors have been used as

regression tools to predict quantitative measures of deterioration such as

crack growth rate, moisture accumulation or structural displacement. These

models are effective in the estimation of long-term material behavior utilizing

both historical and sensor based data.

Isolation forests

and autoencoders are anomaly detection models that are specialized at detecting

unusual deviation of normal structural behavior and can be used to detect

micro-fractures or abrupt environmental stress early. Such models have an added

advantage when the number of labeled datasets is scarce.

Deep learning and

their neural networks are effective at handling nonlinear associations and high

dimensional data. Surface imagery (convolutional neural networks or CNNs) can

be used to identify early signs of structural instabilities such as erosion or

corrosion, whereas time-serial sensor readings (recurrent neural networks or

RNNs and LSTMs) are used to predict them. Collectively, these models form a

holistic system of analysis that is able to predict various modes of failure

with a high level of accuracy.

3.3.

MONITORING SYSTEM DESIGN

3.3.1. Types of Sensors

The range of

sensors used in monitoring systems is immense and each sensor has a particular

diagnostic use. Strain gauges detect micro-deformations and determine the

location of stress concentrations which could be the precursor of crack

formation. Accelerometers record vibration patterns due to the wind, traffic or

a mechanical interaction, and so are vital in the dynamic load analysis.

Humidity and temperature sensors monitor changes in the environment that can

cause expansion and contraction of materials as well as weathering on the

surface. These sensors form a continuous feedback system together which

captures the response of the sculpture to environmental exposure as well as

mechanical forces.

3.3.2. Data Transmission, Sampling

Frequency, and Storage

The transmission

of the data is usually based on the wireless protocols: Wi-Fi, LoRaWAN, or the

Bluetooth Low Energy, based on the local conditions and power supply. The

sampling frequency depends on the parameter to be measured: Vibration

measurements can be sampled with high frequency whereas thermal measurements

can be sampled with low frequency. Information is stored on edge devices or

sent over cloud servers where it is analyzed over a long period, thus providing

safety in long-term archiving and accessibility to predictive modelling.

3.3.3. Real-Time Processing Pipelines

The real-time

pipelines is used to filter the incoming data, look at

the anomalies, and update prediction models in real-time. Edge computing

devices are used to have rapid initial analysis solving the latency and

bandwidth consumption. At the same time, centralized processing systems

summarize long-term data sets, improve machine learning forecasts and send

notifications in case of the critical thresholds. This real time responsiveness

is an improved measure of early intervention and proactive measures in

conservation.

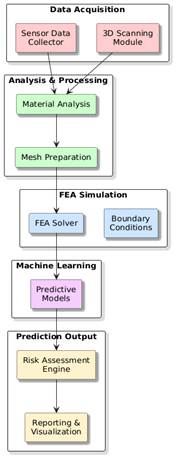

Figure

2

|

Figure 2 System architecture model for Structural Integrity in Sculptures |

4. Predictive Modeling and Analysis

4.1.

STRESS DISTRIBUTION AND

FAILURE MODE SIMULATIONS

The

key part of a predictive modeling process is represented by stress distribution

and failure mode simulations that allow assessing the load behavior in the

sculpture structure. Stress maps under different conditions of environmental

and mechanical loads are produced using the finite-element analysis, such as

gravitational stress, thermal expansion, moisture swelling, and vibrational

forces. These simulations show areas of critical stress concentration, which

points to areas prone to cracking, deformation, or fatigue of material.

Differences in temperature, e.g., generate expansion-contraction cycles that

cause concentration of stresses in joints and thin-sections, whereas mechanical

vibrations cause temporary stress peaks which can build up with time. Possible

failure modes including buckling, surface flaking, shear cracking or tensile

rupture are determined at a very early stage through iterative simulations and

therefore the conservators can prioritize interventions. Changes in

environmental conditions or installation support also can be analyzed using the

simulation platform to determine the effect of changes on stress behavior of a

particular system on a what-if basis. The given predictive ability allows

developing a more advanced strategy of conservation planning and offer

quantitative resources to justify structural reinforcements, material

stabilization, or display changes.

5. Result and Analysis

The crack

propagation and deformation prediction outcomes refer to how the micro-cracks

that are present develop with time as a result of an interaction between the

environmental and mechanical effects. The length of the initial crack as

indicated in the table is a significant factor in the propagation rate as well

as the long-term failure time. Cases whose initial cracks are larger like Case

3 (3.1 mm) have significantly higher propagation rates (0.40 mm/month)

resulting in higher ultimate deformation and reduced time to failure. This

trend shows that crack detection at an early-stage is

very important since the rate of crack propagation increases as stress is built

up at the end of the crack. The risk index is highly related with the

propagation rate and the magnitude of deformation: the cases in which the

tendency towards deformation is higher (1.12 to 1.47 mm) possess a higher level

of risk that surpasses 50 percent meaning that the structural deterioration is

imminent. There is also the phenomenon of environmental load interactions

enhancing crack evolution with swelling due to humidity augmenting the

displacement of crack openings, and vibration accelerated propagation due to

fatigue. The model is used to determine these interactions with time-dependent

simulations and a clear insight into nonlinear degradation patterns is

realized. The deformation values in the table can be used to show how the

displacement is spread beyond the immediate area in the crack, which influences

the stability of the sculpture as a whole. In high-risk cases final deformation

exceeds 1 mm which is a level that may be linked with visible instability in

heritage material.

The predictions of

failure time demonstrate the actual applicability of this model. The highest

rate and risk of case 3 indicate that the failure window is only 11 months,

which is the reason why an urgent intervention is necessary. On the other hand,

less hazardous cases such as Case 2 offer greater timeframes, and the

conservation can be planned and preventive. Taken together, this analysis

provides a predictive perspective in a wholesome manner so that conservators

can group the threats, ranking the intervention areas, and institute specific

reinforcement measures in line with the available empirical evidence.

Table

2

|

Table 2

Sensitivity Analysis Results |

||||

|

Parameter Tested |

Variation (%) |

Impact on Max Stress (%) |

Impact on Deformation (%) |

Stability Rating |

|

Young’s Modulus |

±10 |

18 |

14 |

Medium |

|

Density |

±8 |

6 |

9 |

High |

|

Thermal Expansion Coefficient |

±12 |

22 |

27 |

Low |

|

Humidity Absorption |

±15 |

25 |

31 |

Low |

|

Boundary Constraints |

±5 |

11 |

8 |

Medium |

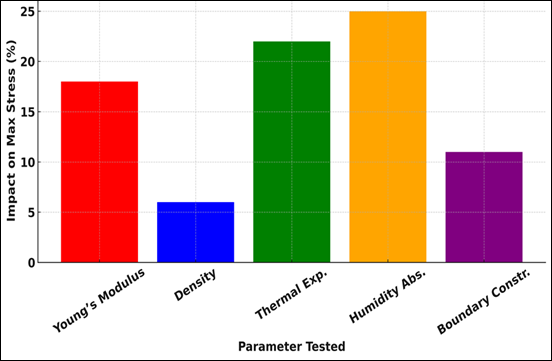

The results of the sensitivity

analysis are shown in Table 2, and they demonstrate the effect of the changes

in the main parameters on the results of the stress and deformation. The

modulus of Young and boundary constraints has moderate effects

so it is possible to conclude that the mechanical stiffness and support

conditions have a strong impact on stress distribution. Density has small

effect, since it has constant effects on structural response as is shown in Figure 3 in sensitivity analysis. On the other hand, the effect on the thermal

expansion coefficient and the ability of the substance to absorb humidity are

the most powerful, which proves that the environmental factor has an enormous

effect on deformation and long-term weakening. The stability ratings also point

to the parameters that need closer characterisation in order to gain predictive

modeling reliability and sound structural simulations.

Figure

3

|

Figure 3 Sensitivity Analysis – Impact on Max Stress |

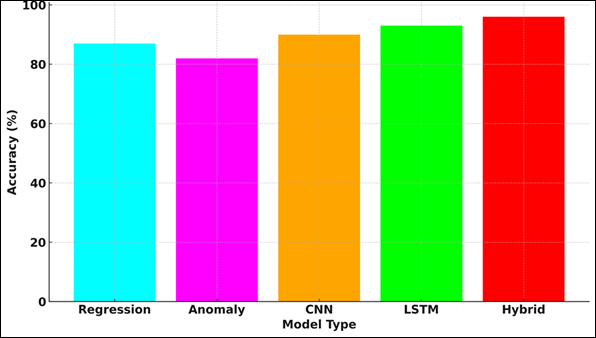

Table 3 is the evaluation of predictive model performance based on accuracy,

RMSE, prediction intervals and metrics of error reduction. The regression and

anomaly detection models have a good performance and have more scattered

prediction ranges due to less trust in small scale deterioration predictions.

The CNN and LSTM models perform better because they can capture both spatial

and time patterns leading to low errors.

Table

3

|

Table 3 Predictive

Model Evaluation Results Analysis |

||||

|

Model Type |

Accuracy (%) |

RMSE |

Prediction Interval (95%) |

Error Reduction (%) |

|

Regression Model |

87 |

0.42 |

±0.88 |

12 |

|

Anomaly Detection |

82 |

0.51 |

±1.02 |

9 |

|

CNN Surface Model |

90 |

0.36 |

±0.74 |

15 |

|

LSTM Time-Series Model |

93 |

0.29 |

±0.62 |

18 |

|

Hybrid Model (ML + FEA) |

96 |

0.21 |

±0.48 |

24 |

The hybrid ML+FEA model is the best as it has the highest accuracy and

minimum RMSE. Its large rate of error minimization shows the usefulness of

integrating physical simulation and machine learning, providing the most

accurate structural integrity forecasts, example of accuracy in Figure 4.

Figure

4

|

Figure 4 Predictive Model Evaluation Comparison of Accuracy |

6. Case Studies

6.1.

APPLICATION

TO HISTORICAL OR CONTEMPORARY SCULPTURES

Both past and

present sculptures were fed in predictive modeling to prove the flexibility of

the algorithmic structure. In ancient stone carvings especially those that have

been exposed to changes in the environment over centuries the models put emphasis on long-term stress corrosion and the

development of micro-cracks caused by the variation occurring in humidity and

thermal contraction. A large number of these sculptures had areas of critical

stress around the joints, excavation cuts, and slender projections, and this

evidence supports the usefulness of digital simulations in identifying

concealed weaknesses. In comparison, the modern metal and composite sculptures

had various degradation characteristics with vibrational fatigue, welding

residual stress, and corrosion-based thinning as the predominant. Predictive

algorithms were able to distinguish these material responses and provide custom

information on the predicted deformation, fatigue life and risk of failure. The

procedure confirmed the usefulness of a 3D scan, FEA, and machine learning

model integration to produce trusted structural predictions on artistic

periods, fabrication styles, and conditions.

6.2.

MODEL PERFORMANCE

COMPARE THE PERFORMANCE OF MATERIALS (STONE/METAL/WOOD/COMPOSITE)

The analysis of

the performance of various materials indicated that there were unique

computational behaviors related to the material stiffness, density, and

degradation mechanisms. In the case of stone sculpture, there was high

conformity in simulation and measured deformation, because of the

elastic-brittle behaviour of mineral substrates which are predictable. The

responses to vibrations were more dynamic with metals where algorithms were

required to be trained with vibration-awareness to gain an appropriate

interpretation of fatigue patterns.

Figure

5

|

Figure 5 Stress Response across Materials |

The sculptures

made in wood yielded more complicated forecasts due to anisotropic grain

patterns and sensitivity to moisture and needed hybrid sensor-ML combination to

make accurate forecasts. Real sculptures showed a consistent performance

because of homogeneous properties, which permit machine learning models to

provide a high accuracy with little tuning as presented in Figure 5.

In general, the predictive framework exhibited a strong cross-material

generalization, and hybrid FEA-ML systems performed better in comparison to

single-model based approaches.

7. Discussion

7.1.

MERITS AND WEAKNESSES OF PREDICTIVE

ALGORITHMS.

Predictive

algorithms have significant value in conservation of sculptures due to the

ability to identify structural weaknesses early, measure stress behavior, and

predict the dynamics of deterioration, which is impossible to track manually.

Their capacity to incorporate environmental information, the material

properties and historical degradation trends generate a comprehensive

information about the structural health. Nevertheless, there are some

disadvantages especially, the requirement of quality datasets, expert

calibration of simulation parameters and the cost of computation with high

density 3D-meshes. Also, machine learning models can have difficulties in

extrapolation when historical data is rare and lumpy or inconsistent and sensor

networks can create noise or gaps in long-term measurements.

7.2.

IMPLICATIONS

TO PRACTITIONERS, I.E. CONSERVATORS AND ENGINEERS.

Predictive

modeling integrated into the processes of conservation enables the conservator

and structural engineers to shift operations of restoration back to

maintenance. These algorithms are evidence-based reinforcement strategy

recommendations, environmental control modification, display configuration

modification and restoration priority. The conservation teams can more

effectively distribute resources by determining the timing when the failure

will take place. The better load simulations have been useful to engineers to

design safer mounting systems, supports and display structures (particularly to

fragile or full-sized artworks).

7.3.

ETHICAL AND PRESERVATION-RELATED ISSUES.

Predictive

modeling should be morally justified so that it does not affect the integrity

of art. The excessive use of intrusive sensors or unneeded support may change

the physical or aesthetic nature of a piece of art. The interpretation of data

should also be open and not based on automated research options without the

supervision of conservators. Ethical principles also favor minimal intervention, i.e. predictive insights ought to be used to

create preventive actions instead of taking excessive restoration. Fair access

to technology is another issue: smaller museums might have financial

limitations, and this will establish an imbalance in the ability to conserve.

7.4.

COOPERATION

WITH MUSEUM AND DISPLAY OUTDOOR PROTOCOLS.

The predictive

insights can be appropriately incorporated into museum and outdoor display

procedures by informing the decision-making process of light deployment, air

conditioning, and physical handling and installation procedures. In the case of

the indoor environments, models can be used to minimize the microclimate

settings, as well as the isolation of vibration to increase the lifewell of the

delicate sculptures. In the out-of-doors environment, the forecasted outcomes

guide preventive actions against weather, pollution and temperature extremes in

the choice of coating, sheltering buildings or seasonal movement. Algorithms

can be used to create alerts that are part of the daily monitoring of museums

and allow the staff to react to the noticed threats. This unification

guarantees the long-term preservation management that is driven by data and is

sustainable.

8. Conclusion

The advent of

predictive algorithms is a paradigm shift in the paradigm of structural

integrity measurement as well as maintenance of sculptures, and a scientific

and proactive addition to the classic forms of conservation undertaking. This

multidisciplinary framework can elucidate the current and future structural

behavior with high precision and accuracy due to the combination of

high-resolution 3D scanning, detailed material characterization, environmental

observations, the finite-element modeling, and sophisticated machine learning

models. Simulation of stress response, prediction of crack propagation and

quantification of deformation patterns help conservators and engineers to

identify emerging risk early before they are apparent, eliminating the invasive

solutions and prolonging the lifespan of artworks. The case studies reveal how

these predictive tools can be used in a wide range of various material,

including brittle stone and anisotropic wood to dynamic metals and modern

composite materials, which is indicative of the flexibility and consistency of

hybrid FEA-ML modeling strategies. Despite the fact that some of these issues

like high-quality datasets, computational requirements, and ethical

considerations that are to be maintained on an ongoing basis persist, the

prospects of predictive modeling provide a strong basis of data-driven

conservation decisions. With the further adoption of sensor-based monitoring

systems in museums and outside heritage sites, some real-time data streams will

enhance the accuracy of algorithms and risk prediction. Finally, predictive

algorithms not only allow contributing to the scientific integrity of

conservation policies but also assist in protecting cultural heritage by making

sure that sculptures are preserved in the least possible way and according to

their historical and artistic potential.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Abdelmalek-Lee, E., and Burton, H. (2023). A Dual Kriging–Xgboost Model for Reconstructing Building Seismic Responses Using Strong Motion Data. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 1–27.

Ao, Y., Li, S., and Duan, H. (2025). Artificial Intelligence-Aided Design (AIAD) for Structures and Engineering: A State-of-The-Art Review and Future Perspectives. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 32, 4197–4224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-025-10264-1

Aziz, M. T., Osabel, D. M., Kim, Y., Kim, S., Bae, J., and Tsavdaridis, K. D. (2025). State-of-the-Art Artificial Intelligence Techniques in Structural Engineering: A Review of Applications and Prospects. Results in Engineering, 28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.107882

Esteghamati, M. Z., and Flint, M. M.

(2021). Developing Data-Driven Surrogate Models for

Holistic Performance-Based Assessment of Mid-Rise RC Frame Buildings at Early

Design. Engineering Structures, 245, 112971.

Gao, C., and Elzarka, H. (2021). The Use of Decision Tree Based Predictive Models for Improving the Culvert

Inspection Process. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 47, 101203.

Hu, S., Wang, W., Alam, M. S., Zhu, S., and Ke, K. (2023). Machine Learning-Aided Peak Displacement and Floor Acceleration-Based Design of Hybrid Self-Centering Braced Frames. Journal of Building Engineering, 72, 106429.

Jayasinghe, S., Mahmoodian, M., Alavi, A., Sidiq, A., Sun, Z., Shahrivar, F., Setunge, S., and Thangarajah, J. (2025). Application of Machine Learning for Real-Time Structural Integrity Assessment of Bridges. Civil Engineering, 6(1), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/civileng6010002

Jin, T., Cheng, X., Xu, S., Lai, Y., and

Zhang, Y. (2023). Deep Learning Aided Inverse

Design of the Buckling-Guided Assembly for 3D Frame Structures. Journal of the

Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 179, 105398.

Ko, H., Witherell, P., Lu, Y., Kim, S., and

Rosen, D. W. (2021). Machine Learning and Knowledge

Graph Based Design Rule Construction for Additive Manufacturing. Additive

Manufacturing, 37, 101620.

Latif, I., Banerjee, A., and Surana, M.

(2022). Explainable Machine Learning Aided

Optimization of Masonry Infilled Reinforced Concrete Frames. Structures, 44,

1751–1766.

Mousavi, M., Ayati, M., Hairi-Yazdi, M. R., and Siahpour, S. (2023). Robust Linear Parameter Varying Fault Reconstruction of Wind Turbine Pitch Actuator Using Second-Order Sliding Mode Observer. Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering Innovations, 11, 229–241.

Rashidi Nasab, A., and Elzarka, H. (2023). Optimizing Machine Learning Algorithms for Improving Prediction of Bridge Deck Deterioration: A Case Study of Ohio Bridges. Buildings, 13(6), 1517. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13061517

Siahpour, S., Ayati, M., Haeri-Yazdi, M., and Mousavi, M. (2022). Fault Detection and Isolation of Wind Turbine Gearbox Via Noise-Assisted Multivariate Empirical Mode Decomposition Algorithm. Energy Equipment and Systems, 10, 271–286.

Yang, L., and Huang, E. (2025). Structural Health Monitoring Data Analysis Using Deep Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering. Association for Computing Machinery, 913–927. https://doi.org/10.1145/3711129.3711286

Zhao, P., Liao, W., Huang, Y., and Lu, X. (2024). Beam Layout Design of Shear Wall Structures Based on Graph Neural Networks. Automation in Construction, 158, 105223.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.