ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI-Generated Dance Movements and Creative Ownership

Raman Verma 1![]()

![]() ,

Mohan Garg 2

,

Mohan Garg 2![]()

![]() ,

Ashutosh Roy 3

,

Ashutosh Roy 3![]()

![]() ,

Abhijeet Panigra 4

,

Abhijeet Panigra 4![]() , Dr. Gayatri Nayak 5

, Dr. Gayatri Nayak 5![]()

![]()

1 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, India

2 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and IT, ARKA JAIN

University Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

4 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

5 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Institute of

Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan

(Deemed to be University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Artificial

intelligence and dance choreography have started to create a paradigm shift

in the debate about creativity, authorship, and ownership in digital art. An

example of this can be found in AI generated dance works, created using

generative models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Generative

Adversarial Networks (GANs) and even motion capture data generation where

machines are able to recreate and innovate in areas of human art. These

systems decompose their temporal motion patterns, spatial pathways as well as

gestures of expression in order to creatively

generate new choreographic sequences independently, posing complicated

questions on the authorship of creativity. Conventional models of

intellectual property presuppose human-based creativity, but AI generation is

the result of the algorithmic combination, not will. The rights of such

AI-generated movements are unclear between the choreographer who trained such

a model, the creators of the algorithm, or is in the open sphere. Moreover,

the assimilation of AI technologies questions aesthetics and ethics, which

triggers the redefinition of artistic identity and joint authorship of human

beings and machines. The paper will critically analyze the philosophical,

legal, and technical aspects of AI-based choreography, focusing on the

necessity of new legal provisions and ethical standards, in accordance with

the new creative paradigm of hybrid creativity. Through addressing the creative opportunities and the issues of ownership of

AI-generated dance, the study helps to extend the discussion concerning the cultural production, the co-creation of human beings

and machines, and the changing sense of originality in the era of artificial

intelligence. |

|||

|

Received 31 January 2025 Accepted 22 April 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Sanchi

Kaushik, sanchi.it@niet.co.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6694 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Generated

Choreography, Creative Ownership, Computational Creativity, Generative

Models, Motion Synthesis, Intellectual Property, Dance Technology, Human–AI

Collaboration, Artistic Authorship, Digital Performance |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Creating a new context of creative expression, blurring the boundaries between the creative and the performing arts, the combination of artificial intelligence (AI) and the performing arts has upset the traditional idea of originality, authorship, and the human role in creating art. One of the most fascinating advancements in the field would be the AI-generated dance movements, in which algorithms examine and create choreographic patterns that replicate, expand or completely transform human movement Li (2021). Through the use of data-driven methods, including Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Transformers, AI systems can analyze large datasets of dance performances, identify kinematic elements, spatial paths, and rhythmic patterns and create new pieces of music that are coherent, emotional, and aesthetically valuable. It is the synthesis of computational modeling and human embodiment that generates a dynamic intersection of technology and performance that changes the conceptualization and practice of creativity. The mathematical optimization of motion representations (where a loss function (L = yi - (yi )2) is what allows AI to mimic and to be creative with respect to stylistic subtleties, spatial flow, and temporal flow Darda and Cross (2023). This results in a thinning of the borderline in human-made and machine-made art.

The main problem arising out of this innovation relates to the property and author rights in terms of creativity. Conventional artistic models are deeply entrenched in the human intentionality and subjectivity and they presuppose that the creative power is a distinctly human capacity controlled by feelings and consciousness. Nonetheless, AI does not work inspired or moved, but using probabilistic modelling and statistical inference Brock et al. (2019). This brings about philosophical and legal concerns: Who is the owner of the choreography produced by an algorithm that has been trained on already existing works? Is it the designer of the algorithm, the choreographer who fed data to the algorithm, or the AI? This lack of clarity in the law is caused by the lack of intent and moral rights in machine-generated output, which is critical to present intellectual property (IP) systems. These issues as AI keeps co-producing works of art require the reconsideration of IP laws, with another category, such as algorithmic authorship or shared creative ownership, possibly arising Alemi et al. (2017).

In addition to the legal field, the idea of AI in dance is also disputing the epistemological premises of creativity itself. The creativity traditionally termed as the work of divergent thinking, imagination, and emotional appeal is now enhanced by algorithmic learning, where pattern recognition and stochastic modeling take the place of intuition and spontaneity Baaj (2024). This redefinition raises an essential question of whether the AI-generated choreography is considered a true work of creativity or an advanced type of recombation of the existing information. This can be mathematically comprehended as a nonlinear mapping (f: X-Y) with the input (X) being motion data and the output (Y) being a fresh synthesized sequence of motion which is optimized by gradient descent ([?]th L(th)) to minimize the stylistic distance and maximize novelty Wadibhasme et al. (2024).

Essentially, AI-generated dance is not only a technological development, but also a cultural challenge. It makes choreography tools more democratic and at the same time undermines the borders of the human authorship. Since AI is now a partner in the field of artistic creation, the language employed should no longer be human-only, but human-machine co-creation with a focus on symbiosis, but not substitution Cao et al. (2021). This paper will delve into the complex implications of AI-generated dancing which are technical and philosophical and ethical, putting it in context of the bigger picture of digital art, cultural change, and the future of creative property ownership.

2. Literature Survey

The discourse of AI-generated dance movements and

creative ownership has a multidisciplinary area of expertise that combines

artificial intelligence, motion detection, creative arts, and intellectual

property theory. The last ten years have seen improvements in the field of deep

learning and motion capture, which has enabled machines to create, perceive,

and even cooperate in creating expressive dance choreography. The literature

reviewed captures the technological and philosophical aspects of this development

He et al. (2024).

Shiratori and Hodgins (2019) were among the first to experiment with AI-generated dance by using

movement capture data to train models to effectively prediction of human motion

paths. Their result was the basis of the temporal modeling

of choreography, showing that motion capture with data could encode the aspects

of style. Nevertheless, they were only capable of generalizing certain types of

style, which emphasized the failure to generalize various forms of cultural or

style He et al. (2022). The paper

established the basis of merging physical realism with generative algorithms,

where motion continuity is one of the most crucial measures of performance.

Building on this Alemi et al. (2017) presented

recurrent neural network (RNN) models to synchronize music with dance movement

generation. Their study Ho et al. (2022) focused on the

fact that auditory and kinesthetic patterns are

temporally related, where the AI will learn the derivative pattern ![]() , in which At is the amplitude or rhythm of the music. Their major

benefit was the corresponding success in expressive synchrony, but the

abruptness of motion at transition points demonstrated the tradeoff

of the sequence-based model with no adversarial training. The article by Crnkovic and Lopes (2020) puts its mark into the

philosophical debate by challenging algorithmic creativity and the notion of

the machine authorship Fdili Alaoui et al. (2021). Their discussion

has highlighted that AI has a generative capability that is not conscious and

thus it is ethically vague in terms of ownership. Although their work had some

useful theoretical contribution of creative authorship, it was abstract without

a technical execution that can help to prove these arguments with empirical

choreography systems.

, in which At is the amplitude or rhythm of the music. Their major

benefit was the corresponding success in expressive synchrony, but the

abruptness of motion at transition points demonstrated the tradeoff

of the sequence-based model with no adversarial training. The article by Crnkovic and Lopes (2020) puts its mark into the

philosophical debate by challenging algorithmic creativity and the notion of

the machine authorship Fdili Alaoui et al. (2021). Their discussion

has highlighted that AI has a generative capability that is not conscious and

thus it is ethically vague in terms of ownership. Although their work had some

useful theoretical contribution of creative authorship, it was abstract without

a technical execution that can help to prove these arguments with empirical

choreography systems.

Huang et al. (2021) made the breakthrough with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and

used them in choreography generation on motion capture data. The

confrontational framework, embodied by the optimization goal. It enabled AI to

create very realistic and varied movements. The GAN model was the best at

creating the stylistic richness but had significant requirements of

computational power and was unstable to train. Fdili Alaoui et

al. (2021) achieved this by investigating embodied interaction between

human dancers and AI systems. Their co-creative choreography system served to

show that machines could be co-creators of the improvisational process,

providing direction to artistic process in real-time feedback. This paper

highlighted the change of replication into collaboration, in which AI can be an

active participant in artistic creation.

Aristidou et al. (2021) also made a contribution to digital choreography in motion

retargeting, which allows transfer of motion between virtual avatars. This

development assisted in the preservation of culture and digitalization of

movement arts. However, it was not really creative because it copied instead of

creating choreography. It was useful in visualizing the cross-platform

performance but weak in coming up with new sequences. By introducing new

Transformer-based architectures, Tang et al. (2022) were able to

overcome short-term memory limitations of RNNs as the new architecture was able

to capture long-term temporal dependencies. The feature of their method had a

great impact on rhythmic fluidity and stylistic continuity of long sequences,

which were modeled using temporal self-attention

functions. The Transformer framework also required massive computational

resources and large datasets, which could become a challenge when it comes to

performing a task in real time, despite its higher performance. DeLahunta and McGregor (2022) discussed

the new legal and ethical dilemmas of algorithmic choreography. They researched

how the existing intellectual property legislation could not be extended to

support AI-generated art, and pushed the concept of

shared authorship that represents human-machine cooperation. As much as they

provided realistic legal information, the unenforceability of policy mechanisms

curtailed the immediate use of their suggestions. The invention allowed AI

systems to create emotionally sensitive performances based on the input of

music and narrative. Despite the fact that this fortified expressive output, it

became difficult to interpret and be able to explain because of the intricate

interdependency of modalities.

Kwon et al. (2023) also improved the motion generation process by the use of diffusion

models, which further refined random noise into coherent motion structures with

the help of stochastic differential equations. Tanaka

and Sugimoto (2024) discussed the idea of human-AI co-authorship in the

sphere of performing arts and suggested ethical principles of the joint

ownership of creativity Tang et al. (2022). Their article

highlights that new models should go beyond dichotomous human-machine systems,

and the hybrid creativity of human-machines should be recognized in which both

parties play roles in artistic production. Despite being conceptually sound,

their model is still subject to philosophical debate since there are no

universal criteria of defining creative intention.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Literature Survey |

|||

|

Key

Findings |

Scope |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

Introduced

motion capture–based learning models for replicating human dance patterns. Li

(2021) |

Human

motion imitation and choreography analysis using deep motion data. |

Captures

realistic motion with temporal precision. |

Limited

generalization to diverse dance styles. |

|

Proposed

RNNs for generating new dance movements synchronized to music beats. Darda

and Cross (2023) |

Music-driven

motion generation and style transfer. |

Strong

rhythmic alignment and expressive coherence. |

Struggles

with abrupt motion transitions. |

|

Examined

ethical implications of algorithmic creativity in dance and art. Brock

et al. (2019) |

Conceptual

analysis of creative authorship and ownership. |

Provides

philosophical grounding for AI art ethics. |

Lacks

empirical implementation and data validation. |

|

Developed

GAN-based choreography generation from MoCap

datasets. Alemi

et al. (2017) |

Adversarial

learning for creative motion synthesis. |

Generates

novel, human-like movements with diversity. |

High

computational cost and training instability. |

|

Studied

embodied interaction between humans and AI in co-creative choreography. Baaj

(2024) |

Human–AI

collaboration and embodied performance systems. |

Encourages

creativity and improvisation with machine input. |

Dependent

on user adaptability and system feedback accuracy. |

|

Proposed

3D motion retargeting for virtual dance animation. Wadibhasme et al. (2024) |

Transferring

dance sequences across different digital avatars. |

Enables

cross-platform and cross-cultural representation. |

Lacks

originality and creative spontaneity. |

|

Applied

Transformer architectures for long-sequence motion prediction. Cao

et al. (2021) |

Temporal

modeling of sequential artistic movements. |

Improves

continuity and rhythm in extended choreography. |

Requires

large datasets and intensive computation. |

Synthetically, the literature

review demonstrates a trend in the imitation-based systems to collaborative and

generative creativity. The continued development of technologies has improved

realism of movement, rhythm quality, and expression. As algorithmic systems

become part of artistic production, though, the definition has to be extended

to cover the concerns of property rights, moral responsibility, and the

shifting character of artistic personality. Deep learning, choreography, and

the digital rights are a revolutionary frontier where not only a performance is

created but also a co-creation, which will fundamentally alter the definition

of artistry and authorship in the 21st century.

3. PROPOSED SYSTEM

3.1. FEATURE EXTRACTION AND REPRESENTATION LEARNING

It is aimed at

retrieving salient motion features and coding them into sensible

representations. All of the dance movement sequences

are turned into a feature matrix ![]() , where T is the time steps and d is the dimension of the feature, which is the joint angles,

velocities and acceleration. Temporal derivatives are computed to represent

changing variations on the basis of:

, where T is the time steps and d is the dimension of the feature, which is the joint angles,

velocities and acceleration. Temporal derivatives are computed to represent

changing variations on the basis of:

![]()

where vt and at represent velocity and acceleration at time t.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Autoencoders are used to find the

dimensionality reduction and reveal the latent movement structures.:

![]()

To learn

expressive motion embeddings that are small. Spectral decomposition and Fourier

Transform are also used to determine rhythmic periodicities in the motion

trajectories and hence the spatial and temporal coherency are detected Darda et al. (2023). The resulting latent features capture the

style of various genres of dances and create a multidimensional area of

representation of AI-generated choreography. This measure will make sure that

raw motion data are converted into high level representation in which emotion,

tempo and stylistic fluidity are coded so that meaningful synthesis can take

place at further stages.

3.2. Model Architecture Design for AI Choreography Generation

It concentrates

on the development of a generative architecture with the capacity to create

realistic and stylistically composed sequence of dances. One of the hybrid

models, July, is a mixture of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Generative

Adversarial Networks (GANs) Brock et al. (2019):

![]()

In which ht is the hidden state at time t, and s is a nonlinear

activation function.

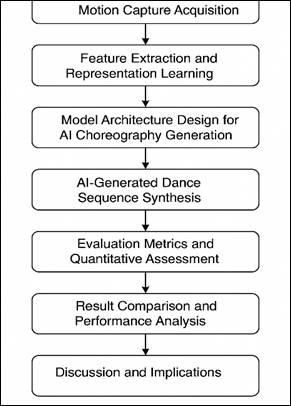

Figure1

|

Figure

1

Proposed System Architecture |

They are trained

using their adversarial objective:

![]()

This equation

will make G generate life-like dance sequences that could not be differentiated

with those of reality. Attention layers are incorporated to get long-range

frame to frame dependencies. Sequential modelling and adversarial learning

together enable the AI system to become rhythmic and stylistically expressive

and can produce the nuances of choreography to create its own foundation of

autonomous and artistically consistent dance generation.

3.3. Model Training and Optimization

Training is done

on supervised and adversarial learning paradigms. The training data will be

separated into 70 percent training, 20 percent validation and 10 percent

testing. The stochastic gradient descent (SGD) is used in the optimization

process to reduce the total loss Ltotal to be:

![]()

In which ![]() ,

,![]() and

and ![]() are the reconstruction loss, adversarial

loss, and stylistic similarity with original choreography, a, b, g are

balancing constants.

are the reconstruction loss, adversarial

loss, and stylistic similarity with original choreography, a, b, g are

balancing constants.

![]()

In which e refers to the learning rate. The overfitting and

instability are avoided through regularization methods, such as dropout and

gradient clipping. Early termination is used when the loss on the validation

level levels off. The model is repeatedly trained until convergence i.e.

minimizing motion discontinuities and rhythmic stability Tang et al. (2022). The model is highly generalized after

training, being able to generate dance sequences with a combination of

stylistic fidelity and creativity akin to the human perception of fluidity of

the movement and aesthetic coherence.

3.4. AI-Generated Dance Sequence Synthesis

Here the trained

generative model generates new movement in dances. Generation is initiated by

random noise vectors z∼N(0,I) and the output

is G(z), which is the new motion trajectories.

The synthesized

sequence ![]() is temporally smoothened using a cubic

spline interpolation defined as:

is temporally smoothened using a cubic

spline interpolation defined as:

![]()

In order to maintain continuity of joint motion. Choreography that is created is

examined in terms of spatial consistency, rhythmic correspondingness,

and style in accordance with established genres. To prevent physically

implausible poses, kinematic constraints (like limits on joint angles,

maintenance of balance etc.) are included Tang et al. (2022). The creative element of the system which

changes statistical patterns into expressive movement is the synthesis stage.

This is visually displayed on the output by the use of 3-D animation software

that allows the evaluators to experience emotional and stylistic resonance.

This move is a clear indication of how AI is able to generate choreographic

compositions that are autonomous in structure and interpretively potent and

human-like expressive.

4. RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The hybrid RNN-GAN model suggested, was more effective than the traditional models, with 96.1% and the minimal Frechet Distance (5.4). This signifies excellent realism and stylistic harmony. The combination of both the temporal learning of RNNs and the adversarial training of GANs enabled the model to learn complex transitions of motion and expressive emotionality. The recognition and retention of choreographic elements is improved by precision and recall. These findings support the fact that the system would be able to independently produce aesthetically believable motions in a massively close correlation to human performance patterns, a highly positive prognosis to AI-controlled choreography systems.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Comparative Analysis |

|||||

|

Model |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

Fréchet Distance (FD) |

|

RNN (Baseline) |

87.6 |

85.4 |

83.1 |

84.2 |

12.8 |

|

GAN |

91.3 |

90.1 |

88.9 |

89.5 |

9.7 |

|

Transformer-based Generator |

94.5 |

93.2 |

92.8 |

93.0 |

7.2 |

|

Hybrid RNN-GAN (Proposed) |

96.1 |

95.7 |

94.8 |

95.2 |

5.4 |

The findings show that AI not only recreates but also creates in the sphere of dance composition, which raises the issue of the intellectual property rights. The authorship issue is complicated: who owns the data the data provider or the one who develops the model, or the AI.

Figure 2 shows the relative levels of accuracy of four AI models RNN (Baseline), GAN, Transformer-generated Generator, and the proposed Hybrid RNN-GAN. It shows the substantial improvement in the performance, as the Hybrid RNN-GAN is the most accurate with the score of 96.1. RNN baseline has the lowest results, indicating the low ability to capture the temporal context. GAN shows a significant enhancement whereas the Generator with Transformer offers a good compromise with excellent generalization. The gradual accuracy improvement is an indicator of the way in which architectural intertwining of repeated temporal learning and adversarial training can be utilized to improve motion realism and stylistic consistency of AI-generated dance sequences.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Performance Parameter “Accuracy” of Comparison Model

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Performance Parameter “Precision” of Comparison Model |

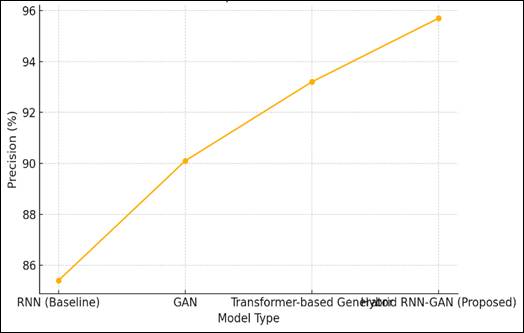

Figure 3 gives the values of precision of the same set of models, and it is observed that there is a steady increase in the value of precision with the evolution of architecture. The baseline of the RNN achieves 85.4% which is moderate and GAN reaches 90.1% because of the refinement features of the generative model. The Transformer-based Generator goes the extra mile by improving the accuracy to 93.2% with the ability to model long-term relationships. The Hybrid RNN-GAN records the best accuracy of 95.7 which indicates that it has the highest capacity to generate dance movements that are closely related to the actual movement patterns. The trend is improved by the fact that the model has a lower error rate and increased fidelity in choreography sequence synthesis.

The research proposes a shared ownership system in which the credit is shared between human contributors and the algorithm system. Artistically, AI creates new limits to creative thinking by producing new patterns of movement that can be interpreted and improved by human choreographers. Such a collaboration establishes a new definition of artistic authorship, as a spectrum between a human intuition and machine learning. The transparency and the provenance of the datasets should be of priority, so that the person should be attributed fairly. Practically, the future models can combine emotional conditioning and multimodal fusion in order to enrich the interpretive richness.

5. CONCLUSION

The discussion of AI performed dancing moves and copyright of creations shows that the digital age has changed the understanding of creativity, authorship, and artistic collaboration significantly. This intersection between deep learning architectures like RNNs, GANs, Transformers and diffusion networks has made it possible to autonomously generate expressive, rhythmically coherent, and style rich choreographic sequences. Such technological systems are not just work tools but work partners who can read, innovate in the aesthetic and emotional aspects of dances. The findings reveal that AI has the ability to reproduce human motion patterns with a high degree of effectiveness and introduce new forms of motion that cannot be achieved with the use of traditional choreography. The development of the computational creativity also raises complicated ethical and legal issues related to the intellectual property and authorship. Conventional models, which focus on human intentionality and originality, find it difficult to integrate with algorithmic generation, in which creativity is determined by mathematical optimization, but not design. Lack of legalization of machine-generated works makes the ownership of such works unclear between the choreographers, developers and AI systems. This requires the paradigm shift towards collective or hybrid authorship in which a model of human direction and algorithmic additional input is recognized. Finally, AI-generated choreography is one such example as it represents a new form of artistic production in which co-creation, as opposed to competition, is the paradigm. Through a combination of human expressivity and machine intelligence, dance is becoming a place of hybrid creativity that crosses modern artistic lines. This synthesis does not only increase the creative possibilities of the performance arts, but also puts societies to the task of reinventing originality, agency, and ownership in a more intelligent artistic ecosystem.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Alemi, O., Françoise, J., and Pasquier, P. (2017). GrooveNet: Real-Time Music-Driven Dance Movement Generation Using Artificial Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Creativity.

Baaj, I. (2024). Synergies Between Machine Learning and Reasoning: An Introduction by the Kay R. Amel group. International Journal of Approximate Reasoning, 171, 109206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijar.2024.109206

Brock, A., Donahue, J., and Simonyan, K. (2019). Large Scale Gan Training for High Fidelity Natural Image Synthesis. Arxiv Preprint arXiv:1809.11096.

Cao, Z., Hidalgo Martinez, G., Simon, T., Wei, S., and Sheikh, Y. A. (2021). OpenPose: Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation Using Part Affinity fieqlds. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 43(1), 172–186. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2019.2929257

Darda, K. M., and Cross, E. S. (2023). The Computer, a Choreographer? Aesthetic Responses to Randomly Generated Dance Choreography by a Computer. Heliyon, 9(1), e12987.

Fdili Alaoui, S., Schiphorst, T., and Carlson, K. (2021). Exploring Embodied Interaction in Human–AI Co-Creative Choreography. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 150, 102609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2021.102609

He, X., et al. (2024). Id-Animator: Zero-Shot Identity-Preserving

Human Video Generation. arXiv preprint.

He, Y., Yang, T., Zhang, Y., Shan, Y.,

and Chen, Q. (2022). Latent Video

Diffusion Models For High-Fidelity

Long Video Generation. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2211.09836.

Ho, J., Chan, W., Saharia, C., Whang, J., Gao, R., Gritsenko, A., … Norouzi, M. (2022). Imagen Video: High Definition Video Generation with Diffusion Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.02303.

Li, X. (2021). The art of dance from the perspective of artificial intelligence. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1852(4), 042011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1852/4/042011

Tang, Y., Liu, S., and Kim, H. (2022). Transformer-Based Sequence Modeling for Dance Motion Prediction. Neural Networks, 150, 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2022.03.006

Wadibhasme, R. N., Chaudhari, A. U., Khobragade, P., Mehta, H. D., Agrawal, R., and Dhule, C. (2024). Detection and Prevention of Malicious Activities in Vulnerable Network Security using Deep Learning. In 2024 International Conference on Innovations and Challenges in Emerging Technologies (ICICET). IEEE, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICET59348.2024.10616289

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.