ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Curating AI-Generated Artworks: Challenges and Solutions

Smitha S P 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Sunita Samanta 2

,

Dr. Sunita Samanta 2![]()

![]() , Shikha Gupta 3

, Shikha Gupta 3![]() , Manish Nagpal 4

, Manish Nagpal 4![]()

![]() , Prakriti Kapoor 5

, Prakriti Kapoor 5![]()

![]() , Ruchika 6

, Ruchika 6![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Computer Science and Engineering, Presidency University, Bangalore,

Karnataka, India

2 Department

of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Institute of Technical Education

and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be

University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

3 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida

international University, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

4 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

5 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura,

Punjab, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering (AI),

Noida Institute of Engineering and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh,

India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The fast

growth of artificial intelligence (AI) in the creative field has changed the

way curators do their jobs and brought up difficult psychological, moral, and

technical issues. Artworks created by algorithms, neural networks and

generative models that are created by AI challenge traditional concepts of

creation, ownership and aesthetic judgement. This essay examines how the

roles of managers are evolving as they work to link the actions of humanity

with those of machines. It considers the key issues raised when attempting to

organize AI art: challenges related to challenges of authenticity,

originality, ambiguous ownership and copyright, and the technology's black

box decision-making process. It's harder for curators

job due to ethical problems with data-bias and figuring out who wrote a

piece. On a functional level, it's difficult for managers to make sense of

and to put their stake in works that it's difficult to understand the

creative processes of systems that are not always clear. The paper talks about

new ways for humans and AI to work together in curating, ways to judge the

intellectual and stylistic value of something, and ways to include

algorithmic openness in the design of a show. It displays the best practices

and new ways of curating digital art through examples of big AI art shows and

attempts by institutions to set moral standards. |

|||

|

Received 22 January 2025 Accepted 17 April

2025 Published 10 December 2025 Corresponding Author Smitha S

P, smitha.sp@presidencyuniversity.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i1s.2025.6679 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI Art Curation, Generative Models, Authorship and

Ethics, Algorithmic Transparency, Human–AI Collaboration, Digital Aesthetics |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

When the artificial intelligence (AI) and the arts intersect it alters how we consider creation, authorship, and art's value. Artistic creation was previously considered an exclusive prerogative of human beings. Now we live in a time when algorithms, neural networks and machine learning models can make complicated, emotional, and sometimes uncertain works of art. AI systems have been capable of amazing things, from copying to creating brand new things and even inspiring, in everything from music and art to poems and theatre. While these changes make it easier for artists to express themselves, it also makes it extremely difficult to follow the rules that have been used for the collection, analysis and understanding of culture. In the past, it was the job of the curator to place human creation in its proper perspective. Now, the work of the curator must be an effort between human and nonhuman agents in the construction of meaning. AI-generated art isn't just a new medium, it's a reflection of the way technology can coauthor an artwork, how algorithms can be used to make beautiful art, and how data can be used to drive creativity. Generative adversarial networks (GANs), diffusion models and large-scale language-image systems such as DALL. E and Midjourney can create works of art that make it difficult to discern purpose and the computational process.

As more and more art institutions and public digital spaces employ these technologies, curators now have to work out how to interpret works of art created by complicated algorithms; how to navigate the ethical and legal questions of authorship; and get people engaged in the growing conversation around machine creativity Feuerriegel et al. (2024). Curating AI art is then not only an aesthetic job, it's also a job of knowing what is right and wrong and how to do it. Even though AI-made art is showing up more and more in galleries, online platforms and culture institutions, the rules for showing and judging it are still not well developed. Traditional works of art are often from clear artistic traditions and cultural settings.

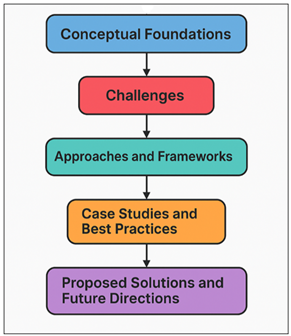

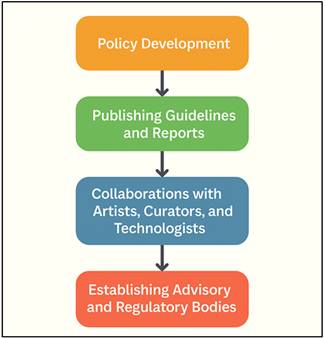

Figure 1

Figure 1 Process Framework for Curating AI-Generated Artworks

AI-generated works, on the other hand, are the result of huge data sets, coded parameters and random outcomes. A collaborative ethical transparent process between human curators and AI creativity is revealed in Figure 1. This creates a more difficult task in determining what something really means. Someone or something can be said to "create" an AI work of art. Who decides and arranges the end result? Is it the computer, the information, the system or a person? These kinds of questions challenge established ways of curating that uses human purpose to judge the importance of art.

2. Conceptual Foundations

1) Definition

of AI-generated artworks

AI-generated artworks are creative works which are made entirely or partly by computer programs which use mathematical models to copy, improve or rethink human creation. On the traditional digital art, the artist works directly with the digital tools. AI art, on the other hand, is that which originates from programs that produce material independently of information and trends that they have learned Kshetri (2024). By analysing large quantities of data and generating new combinations of shapes, colours, and concepts, neural networks, generative algorithms and other AI-based systems can be employed to create drawings, music, poems, and multimedia pieces. It is because of this that AI-gen art occupies a special place between human will and machine action. The artist or coder determines the parameters, datasets and models, and the algorithm searches for potential changes to be made within these limits. Often, the results are so surprising even to the people who made them. What is unique about art generated with AI is that it is rethinking creation as an evolving process between humans and computers Amoozadeh et al. (2024). The beauty of a piece of art is often not just in the picture or arrangement itself, but in the system, training data and artistic process that went into making it. So, art created by AI brings up the question of who created it, what it means and how it should be understood. As a result, they are questioning the notion that art is solely made by humans, adopting an interest instead in data, algorithms and human selection in conjunction.

2) Overview

of generative models and creative algorithms

Generative models and creative algorithms are the technologies that make AI generated art possible. The goal of these computers is to find the patterns in the current data and then to make new results that are similar to those or build up the patterns they found. Generic Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variation Autoencoders (VAEs) and the diffusion models are some of the better known methods. GANs work by letting two neural networks to work with one another in a dynamic way, generator makes data and discriminator checks to see if it is real Allen et al. (2024). The results have the ability to be creative like a person. Newer and more powerful diffusion models utilize learnt denoising processes to transform random noise into pictures in order and over and over again. This allows them to come up with very detailed and creative graphical results. Creative algorithms can be used to write, make music, and videos as well as visual art.

3) The

role of human curators in AI-driven creativity

This means knowing about how numbers are put together and how biases can affect the results of creative processes and how generative processes relate to the goals of art. Curators are the mediator between machines and people to make each other better understood Michel-Villarreal et al. (2023). They discuss the relationship between the human coder, the AI model and the end piece of art, placing that in the context of broader discussions on creativity, innovation and digital ethics Sarkis-Onofre et al. (2021). They also are very important for openness because they reveal the mathematical processes which are typically hidden behind the "black boxes" of AI systems. This level of openness allows trust building and critical thinking of the viewers. In addition to which meaning the art should be depicted with, managers also choose how people should experience and think about their art. Table 1 presents some significant studies, exhibitions, frameworks and institutional contributions. They decide how dynamic, immersive, and math works are displayed that make people think about the ways people and machines can work together.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work on AI-Generated Art and Curation |

|||

|

Focus Area |

Methodology |

Key Findings |

Relevance to Curation |

|

Generative Adversarial Art |

AI trained to create novel artworks autonomously |

Demonstrated machine creativity beyond style

imitation |

Challenges notions of authorship and originality |

|

AI art installation Dari et al. (2024) |

GANs used for real-time portrait generation |

Explored continuous creativity and randomness |

Influences live curation and generative displays |

|

Ethical critique of datasets |

Visual analysis of image databases |

Exposed surveillance bias in AI datasets |

Promoted transparency and ethical curation |

|

AI and culture Chan and Lee (2023) |

Interactive exhibits |

Integrated art, science, and philosophy of AI |

Established interdisciplinary curatorial model |

|

AI artwork commercialization |

GAN-generated portrait |

First AI artwork sold at auction ($432,500) |

Highlighted market and valuation challenges |

|

Artistic–technical collaboration |

Research residencies |

Promoted co-creation among artists and coders |

Model for interdisciplinary curation |

|

Ethical AI design Hamed et al. (2024) |

Case studies and exhibitions |

Proposed guidelines for responsible AI display |

Informed museum-level curatorial standards |

|

Responsible innovation |

Collaborative research |

Merged AI development with art ethics |

Framework for fair and explainable curation |

|

Policy and governance Kaebnick et al. (2023) |

Multi-stakeholder approach |

Introduced principles for human-centric AI |

Adaptable to curatorial governance models |

|

Creative democratization |

Interactive AI interface |

Enabled accessible AI art creation |

Supports participatory and digital curation |

|

Co-creation via GANs |

Web-based remixing |

Encouraged communal authorship |

Expands online and public engagement in AI art |

3. Challenges in Curating AI-Generated Artworks

1) Authenticity

and originality concerns

One of the most difficult aspects of collecting AI-made art is determining what constitutes a computer product as real and unique. Traditional ways of judging art are dependent on the artist's personal vision, artistic purpose, and personal involvement which are all things AI systems can't do. Because AI models learn from vast numbers of existing works, the patterns, styles, or arrangements created by AI models are often merely imitations or parodies of pre-existing ones. This causes people to have anxiety about derivation and repetition Malik et al. (2023). It's difficult to determine the originality of AI art in which the arbitrary process of creation relies not on ideas, but on data collected previously. Also, AI-generated art challenges traditional ideas of validity, which have traditionally put a lot of weight on the artist's mark and skill. In the case of AI art, the "hand of the artist" is replaced by computers, which makes it difficult to discern the difference between being an author and automated. So, there is a need for curators to rethink as to what a real creative act is, whether it's writing an algorithm or organising data or selecting how to display the result for aesthetic reasons Johnson (2023). This doubt also alters the way the viewer perceives things. People may wonder if this AI art has any kind of emotional depth, or if it is simply copying the creativity of humans. In this way, realism in AI art isn't so much having a unique style as it is being upfront with the process and the intentions of the artist.

2) Copyright

and intellectual property issues

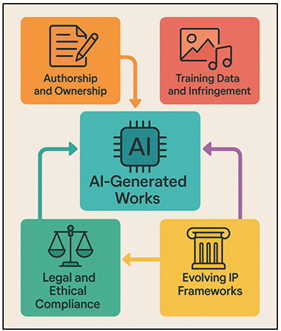

Copyright and intellectual property (IP) conflicts make it hard to collect works of art made by AI. In traditional art, the creators can be pinpointed down as human beings. But with AI art, it's more difficult to say who made it given that it was made by coders, data coaches, users, and the AI system itself. The current rules of copyright are mostly anthropocentric, which means they only recognise writing by humans. As such, AI-generated works will very often fall into legal murky areas, making it difficult for artists and institutions to have a good understanding of what the rules are for business use, copying, and display rights. The samples which are used to train generative models are another controversial topic.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Framework for Managing Copyright and Intellectual Property in AI Art

A lot of times, these files contain protected materials such as photos, designs and artworks that have been stolen from the internet without the creators permission. Figure 2 shows the process of copyright management, attribution of copyright ownership and ethical protection. Because of this, A.I. generated products could potentially copyright content without the intent of doing so, and this could lead managers and venues to potentially get into legal trouble. It's very hard to figure out where AI artworks come from when algorithms work like "black boxes" which makes it hard to find inspirations or sources. In order to handle these intellectual property issues in a managerial role, you must be aware of the law and mindful of social issues Shambharkar et al. (2025). They have to check usage rights, talk to lawyers and make sure that works on display abide by copyright rights and fair use rules. Also, institutions are beginning to advocate for new intellectual property regulations that recognise the fact that people and AI systems can collaborate to produce works.

3) Technical

challenges in understanding AI systems and outputs

This lack of clarity, which is often called the "black box" problem, makes it very hard for editors to understand, analyse and show AI artworks in a useful way. The technological issues include not only the comprehension aspect but also the organizational aspect of the show. For AI art to be exhibited, it may require special hardware or software settings, or constant data connections. All of these things require people who are artists, programmers and engineers to work together across disciplines. This is because unlike printed pieces, algorithmic installations/interactive works do not have a straightforward process of showing, as they require frequent updating, problem-fixing, and computer resource management. Also, managers have to cope with the fact that dynamic systems are difficult to forecast. Because the results of AI can change from one version to the next, the decision of which version it should display and how to frame its change is simultaneously a philosophical and technical decision.

4. Approaches and Frameworks for Curation

4.1. Human–AI collaborative curation models

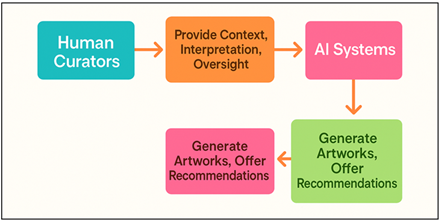

Human-AI joint curation is a newly conceived framework for planning art exhibitions, based on the idea that the human editors' semantic interpretation and the AI's computational power can be combined effectively in planning the optimal displays. This model doesn't view AI as simply a medium for creation of art. It considers it as a partner in the decision making for curators. AI can help with things like looking for patterns in art, guessing how interested an audience will be or finding themes that run through huge art collections.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Framework of Human–AI Collaborative Curation

A human editor, on the other hand, provides valuable background knowledge, emotional awareness and moral course. Figure 3 illustrates the combination of human curators and AI systems in curation. The combination of machine and people can create a flexible system with the precision of machines and the intuition of people. In these types of joint models, AI systems could suggest artworks based on the visual or conceptual similarity, create information, or model the show plans based on the expectation of how visitors will move through the space. Then, the curators can make these ideas better so that they align with artistic stories, institutional purposes, or cultural objectives.

4.2. Criteria for evaluating aesthetic and conceptual value

In order for us to decide the artistic and intellectual value of works that are produced by AI, we have to re-evaluate the criteria that we usually use to assess art. Other traditional criteria such as originality, skill and emotional expression should be modified in order to consider a level of artificial construction, process transparency, and human-machine collaboration. AI art is often a statistical mishmash, not necessarily an emotional experience. This means directors must consider visual or physical attractiveness of the outcome as well as intellectual meaning of the process. Aesthetic evaluation can comprise structural, novelty, and creativity of the AI system. Conceptually, managers ought to consider how well the work questions the relationship between the technology and the mind, and if there's important new information regarding a data culture, authorship, or perception. Often, the value of AI art is not in itself a piece of art but in making people consider the essence of what it means to create. Transparency and interpretability are becoming very important in the evaluation process.

4.3. Integration of algorithmic transparency in exhibition design

1) LIME

LIME's approach to making algorithms more clear is to make models that are easier for humans to understand that show how AI systems make decisions. When creating a show, LIME can be used to see how various elements of an artwork - color, structure, shape etc. - interact. Side by side examples displayed by curators can also demonstrate how slight changes to the AI's input can produce enormous effects on its artwork. By decoding the meaning of the local decision boundaries, viewers of the film see how algorithmic thinking operates rather than just the results of algorithmic thinking. Adding LIME visualization to the experience of shows transforms them into learning experiences, allowing guests to realize why each object was created or to support curators' narratives about how we can make sense of things, who made things, and how humans and machines can collaborate.

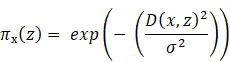

Approximate the complex model f(x) locally with a simple interpretable model g(x),

![]()

Assign weights to samples near the instance x₀ using a proximity function,

Minimize loss to make g faithful to f,

![]()

Using visuals and audience interaction technologies, LIME illustrates what features contribute, by showing how small changes to the input change the output of the system. This facilitates the understanding of the model's local reasoning in a transparent way to the audiences and bridges the gap between computational logic and human understanding.

2) SHAP

Based on the concept of cooperative games, SHAP provides us with a mathematical means to interpret the contribution of each input to the final decision of an AI model. In AI art shows, SHAP can be used to make heatmaps or feature-importance plots which show which parts of the information had the most impact on the end piece of art. They can use these visual clues to discuss the objectives of the algorithm, such as how it takes things into account such as structure, colour schemes or style references. By displaying SHAP analyses, exhibits instill openness and moral sensibility by illustrating how creative decisions are made through the use of quantifiable model reasoning. This gives credibility to people and opens a critical discussion about data bias and computer interpretation.

Represent the model prediction as a sum of feature contributions,

![]()

Compute each feature’s contribution using the Shapley value formula,

![]()

Visualize importance of the features, for interpretability purposes, you may need to visualize the importance of different features.

SHAP also shows how much each attribute (such as tone, contrast, element of the dataset) contributes to the final artistic output of the AI. These calculated contributions can be used by curators to create a visual "importance map", which can be used to communicate to audiences how the thinker places emphasis on specific, artistic features or aesthetics.

3) Grad-CAM

Grad-CAM makes visual explanations by drawing attention to the parts of a picture which have the most impact on an AI model's choice. When choosing AI-made art, one can overlay attention heatmaps on the final picture to see where the algorithm "paid attention" while it was creating the art. Grad-CAM-based exhibitions further render transparent the perceptual reasoning behind neural networks so as to help people understand how computers "see" and understand art. These heatmaps are inserted directly by curators and allow users to toggle between original and activation mapped experiences. This approach is both artistic and technological, making algorithmic opacity into visual statements and enhancing the transparency of curators and the participation of the public in the creative process of AI.

5. Case Studies and Best Practices

1) Notable

AI art exhibitions and curatorial approaches

Over the past decade, numerous shows have featured works of art made by AI, and each had a differing strategy for getting audiences interested in machine craftsmanship. One of the first important events was the exhibition "Unhuman, Art in the Age of AI" (2017). It examined the concept of how computers alter identity in art and the way in which art should be judged. The organisers emphasised process-openness - by showing both the pictures, which are generated, as well as code, which runs them. This caused people to think about the way in which humans and machines can work together. The 2019 show "Training Humans" at Fondazione Prada, put together by Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen, also took a close look at the datasets that are used by AI systems, demonstrating the effect of bias and monitoring on creative outputs. "AI, More Than Human" Barbican Centre (2019) shifted the focus of the exhibition by bringing into view the psychological and societal impacts of AI. The exhibition was a mixture of works of art, science artefacts and interactive pieces, demonstrating that AI art can come from a lot of different fields.

2) Institutional

efforts to define standards and ethical guidelines

As AI art continues to become more popular, cultural institutions are beginning to become more aware of the need to decide on standards and moral rules for how AI art should be curated and shown. Well-known museums, study centres and culture groups are taking the lead in ensuring that the creation of AI is accountable, open, and for everyone. For example, the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) and Tate Modern have already initiated study projects on investigating the ethics of using machine learning in art. Issues related to data source, authorship credit, and algorithmic bias are some of the topics the projects cover. In the same way, the European Commission's Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI (2019) and the Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence (2021) of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) are frameworks which emphasise human oversight, fairness and cultural diversity. Figure 4 illustrates the emergence of institutional responses including ethical normative and regulatory mechanisms. More and more art institutions and curators are implementing these principles.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Institutional Roadmap for Establishing AI Art Ethics

and Regulations

These standards encourage transparency in the methods used for image recognition, the require commas before "and invitations" , permission before using training data, and representation of all peoples.

6. Proposed Solutions and Future Directions

1) Development

of ethical and legal frameworks

New and intelligent models will have to evolve intellectual property rights in a way that makes it fair and transparent for human makers and AI systems to collaborate to make things. Such frameworks should also emphasize data ethics, that is, ensuring that the datasets used to train AI models are acquired legally, with permission, and with cultural sensitivity in mind. To consider the larger social and environmental impacts of AI technologies, ethical rules must address issues such as bias, inclusion and longevity. Institutions should make editorial rules of behaviour that require algorithms and data sources to be made public. This would enable people to make more informed readings.

2) Interdisciplinary

collaboration between artists, curators, and technologists

The future of art created by AI depends on a new collaboration between artists, managers, and scientists. Each group has something else to offer, artists generate ideas and creative visions, organisers contextualise and explicate works, and engineers develop and refine the formulae on whose basis creative work can be done. Interdisciplinary relationships unite these fields and allow people to get to know both the artist and technical aspects of AI art in total. Collaborative projects provide opportunities for people to join forces and create tools that prioritize ethics, openness and transparency. When artists and organisers work with engineers they can have an effect on algorithmic design, making sure that creative systems are in line with artistic purpose and cultural values. These partnerships also increase the editor's technical skills, for instance, learning how to use datasets, how to train models, and their limitations, which enhances the accuracy of their interpretations. Institutions can facilitate this by creating study programs, internships and courses that connect people across disciplines.

3) Use

of explainable AI to enhance curatorial understanding

Explainable AI (XAI) is a necessary move in the right direction for managers who wish to adequately understand and demonstrate works created by AI. Most of the time, traditional AI systems are black boxes that deliver results, but do not explain the reasons behind their occurrence. The goal of XAI is to ensure that these processes are transparent by giving people an insight into how the computer makes certain creative decisions. This capacity to analyse enhances both the technical awareness of a manager and his moral accountability. With the use of XAI tools, curators are able to see how decisions are made, how data is related, and how features affect generative models.

7. Conclusion

This is a turning point in the history of creative practice with the introduction of AI-generated art; this is what makes it necessary to reformulate the concept of an artist, reality, and the role of the curator. Since the computer has increasingly engaged itself in the creation of visual and conceptual works, managing them has to negotiate a complex world, in which human and machine intelligence merge. This revolution questions the traditional ideas about what creative is and needs new models to reconcile creativity with morals, openness and critical thinking. It has come to light that the assembly of AI art does not solely pertain to the exhibition of algorithm-driven pieces of art, but also a question of the interpretation of relations between information, technology, culture, and meaning. The problem of authorship, copyright and social responsibility shows how valuable the creation of full-fledged legal and administrative frameworks, which acknowledge the possibilities of co-creation of humans and AI are, is. Technological and market problems, equally, indicate that managers need to know how to work effectively with programmers, ethicists, and artists. To make people understand the possibility of machine creativity, future formulas of curating should adopt AI to be made known, transparency of algorithms, and learning-by-doing. Therefore, the managers organize the shows where individuals can discuss and critically evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of the AI systems.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Allen, J. W., Earp, B. D., Koplin, J., and Wilkinson, D. (2024). Consent-GPT: Is it Ethical to Delegate Procedural Consent to Conversational AI? Journal of Medical Ethics, 50, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme-2023-109347

Amoozadeh, M., Daniels, D., Nam, D., Kumar, A., Chen, S., Hilton, M., Srinivasa Ragavan, S., and Alipour, M. A. (2024). Trust in generative AI among students: An exploratory study. In Proceedings of the 55th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE 2024) (Vol. 1, 67–73). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3626252.3630842

Chan, C. K. Y., and Lee, K. K. (2023). The AI Generation Gap: Are Gen Z Students More Interested in Adopting Generative AI Such as ChatGPT in Teaching and Learning than Their Gen X and Millennial Generation Teachers? (arXiv:2305.02878). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-023-00269-3

Dari, S. S., Dhabliya, D., Dhablia, A., Dingankar, S., Pasha, M. J., and Ajani, S. N. (2024). Securing Micro Transactions in the Internet of Things with Cryptography Primitives. Journal of Discrete Mathematical Sciences and Cryptography, 27(2), 753–762. https://doi.org/10.47974/JDMSC-1925

Feuerriegel, S., Hartmann, J., Janiesch, C., and Zschech, P. (2024). Generative AI. Business and Information Systems Engineering, 66, 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-023-00834-7

Hamed, A. A., Zachara-Szymanska, M., and Wu, X. (2024). Safeguarding Authenticity for Mitigating the Harms of Generative AI: Issues, Research Agenda, and Policies for Detection, Fact-Checking, and Ethical AI. iScience, 27, Article 108782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.108782

Johnson, W. L. (2023). How to Harness Generative AI to Accelerate Human Learning. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-023-00367-w

Kaebnick, G. E., Magnus, D. C., Kao, A., Hosseini, M., Resnik, D., Dubljević, V., Rentmeester, C., Gordijn, B., and Cherry, M. J. (2023). Editors’ Statement on the Responsible Use of Generative AI Technologies in Scholarly Journal Publishing. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 26, 499–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-023-10176-6

Kshetri, N. (2024). Economics of artificial intelligence governance. Computer, 57, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2024.3357951

Malik, T., Hughes, L., Dwivedi, Y. K., and Dettmer, S. (2023). Exploring the Transformative Impact of Generative AI on Higher Education. In Proceedings of the Conference on e-Business, e-Services and e-Society (69–77). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-50040-4_6

Michel-Villarreal, R., Vilalta-Perdomo, E., Salinas-Navarro, D. E., Thierry-Aguilera, R., and Gerardou, F. S. (2023). Challenges and Opportunities of generative AI for Higher Education as Explained by ChatGPT. Education Sciences, 13, Article 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090856

Sarkis-Onofre, R., Catalá-López, F., Aromataris, E., and Lockwood, C. (2021). How to Properly Use the Prisma Statement. Systematic Reviews, 10, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01671-z

Shambharkar, S., Thakare, K., Takkamore, S., Padole, R., and Chaure, K. (2025, May). Detection of DDoS Attack in Cloud Computing Using Machine Learning Algorithm. International Journal of Electrical and Electronics and Computer Science (IJEECS), 14(1), 239–242.

Zhou, M., Abhishek, V., Derdenger, T., Kim, J., and Srinivasan, K. (2024). Bias in generative AI (arXiv:2403.02726). arXiv.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.