ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Neural Networks in Sound Classification for Art Students

Ayush Gandhi 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. A.C Santha Sheela 2

,

Dr. A.C Santha Sheela 2![]()

![]() , Lakshya Swarup 3

, Lakshya Swarup 3![]()

![]() , Ipsita Dash 4

, Ipsita Dash 4![]()

![]() , Swati Srivastava 5

, Swati Srivastava 5![]() , Dr.

Varsha Kiran Bhosale 6

, Dr.

Varsha Kiran Bhosale 6

1 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura,

Punjab, India

2 Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Sathyabama Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

3

Chitkara Centre for Research and Development,

Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

4

Assistant Professor, Centre

for Internet of Things, Institute of Technical Education and Research, Siksha

'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University) Bhubaneswar,

Odisha, India

5 Associate Professor, School of

Business Management, Noida International University, Uttar Pradesh, India

6 Associate Professor, Dynashree Institute of Engineering and Technology Sonavadi-Gajavadi, Satara, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Sound

classification has become an important element in contemporary creative

practice, in digital art, interactive installation, performance design and

multimedia storytelling. For art students, it not only equips a technological

basis but also a creative toolkit to design novel expressive modality through

neural network understanding of sound: his study of sound emotion mapping

hybrid neural network is equipped with CNN-based spectral extractor, LSTM

temporal mode and Transformer attention learning. Using datasets obtained

from RAVDESS, EMO-DB, and IEMOCAP, the model can promote high accuracy in the

categorical emotion recognition and high alignment in continuous valence

arousal prediction. The attention mechanism allows to improve the

interpretability by focusing on emotionally salient regions of time-frequency

representations. Results indicate that combining spatial, temporal, and

contextual representations facilitates robust and generalizable emotion

mapping to provide a reliable framework for affect-aware audio applications.

The proposed approach furthers the understanding of the interpretation of

expressive sound by neural networks and informs future works in the creative

computing and human-centered AI fields. |

|||

|

Received 18 January 2025 Accepted 13 April 2025 Published 10 December 2025 Corresponding Author Ayush

Gandhi, ayush.gandhi.orp@chitkara.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i1s.2025.6668 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Neural Networks, Sound Emotion Recognition, CNN–LSTM

Architecture, Transformer Attention, Valence–Arousal Mapping |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Sound has always been one of those materials that have been central in the artistic expression. With the growing transformation of the arts into the digital and interactive realm, machine listening is a vital question for perceiving the actual nature of what is being heard. Neural networks have changed the way that sound can be analyzed Mnasri et al. (2022), classed and integrated into creative systems. Art students are encouraged to learn how these models "listen" in order to create artworks that are intelligent, affective, and may even play with the world of sound: Suffice it to say that at the heart of neural sound classification is a simple concept: that machines learn patterns in sound much the way that an artist might learn patterns in color, movement, gesture or narrative tone Madhu and Suresh (2023). A neural network listens to the sound not as a continuous wave but as a structure that resembles a visual and is called mel-spectrogram, representing how the frequency energy changes over time. To a machine, this spectrogram appears as a colorful weaved cloth; to an artist, this looks like a hybrid painting of rhythm and texture İnik (2023). This representation forms the basis on which neural networks form an understanding of the sound categories like ambience, speech, emotion, texture or musical style. Modern neural sound classifiers usually consist of three processing stages Demir et al. (2020).

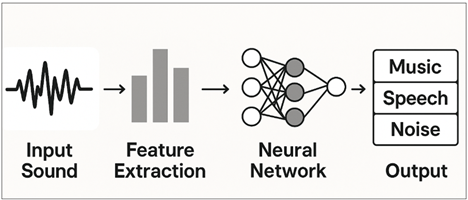

Figure 1

Figure 1 Sound Classification Workflow using Neural Network

Audio Pipeline

They are like image matching engines. From here, Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM) analyze the development of these textures, and representations of sound, and in turn the swell of sound, its decay, its pacing, its emotional momentum are all embedded--a dynamic representation can be seen in Figure 1. Transformer attention mechanisms bring the attention to the most important moments in the sound, and focus the network attention over emotional highs or subtle transitions used to provide emotional weight Ahmed et al. (2020). Together, these elements comprise a rich listening system which emulates both analytical and instinctive elements of human hearing. Not only the importance of neural sound classification, but its value to an art student is shown far beyond technical eloquence. An understanding of such systems attracts new forms of creative experimentation Sivaraman et al. (2021). A neural network should be able to classify the mood of a performer's voice and thus cause changes in the light or visual projections. It is able to detect environmental textures: wind, traffic, ocean waves; helping to drive generative compositions. Technological options enable the interactive artworks to grow in time, assigning expressive aspects to the dancer's breath or the articulation of the musician. As students learn to work with machine listeners they develop a greater understanding of sound as a matter that is not only mediated by human intuition, but algorithmic interpretation Dang (2022).

This paper introduces the principles of neural network-based sound classification by considering the point of view of artistic practice, as a conceptual framework for hybrid CNN-LSTM-Transformer architectures Guzhov et al. (2021). By reduction of technical underpinnings and creative relevancy, the aim is to educate art students about how neural systems hear, interpret and classify sound. In doing so, this work is devoted to promoting the integration of computational listening into arts education in the 21st century so that the next generation of artists can create expressive, adaptive and emotionally intelligent sound-based works of art.

2. Background and Conceptual Foundations

Sound classification is located on the interface between the artistic perception and the computational analysis. To appreciate how the neural networks learn how to interpret audio, the art students must first be able to understand how humans perceive sound, and how they translate their perception into structured information. Artists are often intuitive classifiers of sound - categorizing a voice as anxious or at peace, for example, or describing a sound as metallic or soft, or picking up on emotional charge in a changing rhythm. Neural networks are a similar kind of task but are based on mathematics instead of intuition and learn to spot patterns using large collections of labeled audio Mulla et al. (2024). This section provides the conceptual background on how neural systems and human listeners are able to find common ground. In artistic contexts sound has a lot of symbolic, emotional and experiential meaning. Yet these symbolic and emotional characteristics are also characterized by quantifiable acoustic properties: distributions of tones - their frequencies, dynamics, harmonic composition, and temporal variations of tone amplitudes Triantafyllopoulos et al. (2021). Neural networks use these features that can be measured to categorize sound like emotion, texture, timbre, or scene. The first conceptual pillar is good as a time-frequency structure. Unlike the hearing human listener, machines need a visual-like representation in which both time and frequency are simultaneous. The mel-spectrogram, which is used so much in modern deep learning research and in the model uploaded of emotional audio, is a transformation of the raw waveforms into colorful patterns of color and intensity. High frequencies are stretched out vertically, low frequencies are concentrated near the bottom and temporal variations move horizontally. This Being becomes an equivalent of a chart of the behaviour of sounds. For art students, the mel-spectrogram is a starting point: it converts sound into a representational form that is very well suited to artistic perception, just as a dynamic abstract painting Eskimez (2022).

The second basic concept is recognition of pattern on sound. Neural networks are very good at finding recurring shapes and textures in spectrograms. In addition, CNNs capture low-level visual details by recognizing basic motives on the frequency bands linked to timbral patterns and/or expressive gestures Verbitskiy et al. (2022). Features learned from the surface of touch usually resemble calligraphic strokes or repeating fingerprints. LSTMs take this pattern recognition for more extended periods of time to make sense of how sound morphs or peaks or decays. They are able to capture the emotional flow of audio which is the way speech builds emotion or music builds to climax. We further incorporate an attention mechanism at the final stage, in order to select for the most informative part of the representation with the most expressive power Han (2020). This reflects the principle of artistic listening, whereby one's attention is expected to concentrate the most around meaningful sonic moments.

3. Neural Network Architecture for Sound Classification

Designing a Neural Network that can classify sound for artistic uses requires the understanding of how various computational layers work together to understand audio similarly to how a human would listen to it. The functional concept is quite simple, underpinning the whole process is a complex math, but the idea is quite straightforward: each layer of the neural network picks up different type of meaning of the sound. Drawing on the hybrid CNN-LSTM-Transformer approach for emotional sound mapping at the cutting edge of modern technology, the following section elaborates upon the architecture in a way that is accessible to students in the arts today and which specifies the contribution of each component to the creative possibilities Orken et al. (2022). The architecture starts with audio pre-processing, in which the sound in the raw format is approximated into mel-spectrogram, which is a graphical representation of how the energy at each frequency behaves over time. This transformation is necessary since then neural networks for image processing can analyze sound as if it were a textured surface that moves about. For those students who are already familiar with the visual composition, the mel-spectrogram is an intuitive connector in terms of how students can understand how machines perceive sound patterns in a structured image-like representation. Once the sound is represented in a visual way, model goes in the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) phase. CNNs are like super sensitive pattern recognisers which scan the spectrogram in order to find tiny yet significant details Adusumalli et al. (2025). They respond to such features as sharp transients, smooth gradients, harmonic clusters and rhythmic textures. In terms of artistic impression, CNNs interpret the "brushstrokes" of the sound and capture its local visual patterns and convert them into feature maps Sultana et al. (2025). These maps are the foundations of machine listening, and are maps of the textures and colors of the soundscape.

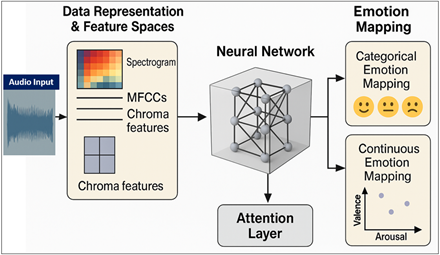

Figure 2

Figure 2 Neural Network for Sound Emotion Mapping

From here the architecture enters the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network which is specialized for understanding the time. Similar to how a musician or performer can feel a sense of movement through time, they learn how to sense emotional arcs, rhythmic pacing, dynamic flow, and the like. For instance, a rising pitch contour can be interpreted by the LSTM as indicating a tense movement, a drawing out of a tone as indicating a soothing movement. In artistic installations or creative AI tools this temporal sensibility can enable the system to interact in a dynamic way with any kind of live performance or sound inputs, as shown in Figure 2. The next layer then introduces Transformer based attention mechanisms, which provide the model with a sort of attention or selective listening capability. Attention computes the relative weight of different elements of the sound to focus on based on which part of the sound is most important in determining the classification - the higher the weight, the more emotionally rich or expressively significant the moment was. This is similar to the way humans tend to concentrate on interesting sonic information - a sudden breath, a coruscating guitar note, or a sudden change of tone. Other, more socially pleasurable applications also result; in creative applications, attention layers enable neural systems to yield more subtle and expressive responses, making the neural interpretation a more appropriate match to the aesthetic accent.

The combined features from CNNs, LSTms and attention mechanisms are passed through dense projection layers to come up with the final classification. These outputs can be specific to emotional categories, sound textures, environmental tags or artistic labels set by the student/designer. What makes this architecture especially powerful is that it is flexible, in that the same structure can be used to classify artistic emotions in spoken word, identify textures in field recordings or distinguish gestures in experimental sound performances.

4. Proposed Neural Acoustic Pattern Extractor (NAPE)

The proposed Sound Emotion Mapping Neural Network architecture has been designed in a way that it learns the emotional cues directly from the raw audio and maps them to a categorical and continuous affective representation. This neural network combines multiple deep learning elements that include feature space transformations, CNT and LSTM neural encoder - a combination, a transformer-based attention mechanism, and finally, the latent emotion projection module to come up with reliable and interpretable emotion outputs. Their central goal is to use a combination of strengths of spatial representation, temporal representation and contextual representation to increase accuracy, generalization across speakers and environments, and sensitivity to the subtle differences in emotional variation occurring in the speech and other types of acoustic signals.

Step -1] Inputs and Front-End: Preprocess audio

Raw waveform x(t)) sampled at fs. Frame with window w(⋅)(length L, hop H):

![]()

The pipeline starts by transforming the raw audio signals into Mel-Spectrograms which are used to get a perceptually synchronized time-frequency representation.

![]()

![]()

Step -2] STFT and magnitude spectrogram

![]()

Mel projection (filter bank Hm(k) =1..M):

![]()

Log compression and normalization:

![]()

Step -3] CNN Feature Extractor

![]()

![]()

with 2-D convolution ∗, ReLU ϕ, batch-norm BN, and (optional) pooling over frequency. Flatten along frequency to get a frame sequence

![]()

To learn the representation further, the log-mel energy is also processed by the model, allowing the model to better compress the dynamic range and be noise resilient.

Step -4] LSTM Temporal Encoder (sequence dynamics)

For time t=1…...T

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Step -5] Flatten to sequence: ![]()

Step -6] Transformer: ![]()

Add positional encoding P and form U=H+P, For multi-head h=1..H

![]()

![]()

![]()

Step -7] Temporal attention pooling: ![]()

Use EMA, Layer Norm and Feed Forward normalization FLN:

![]()

Temporal pooling with learned attention weights αt.

![]()

Step -8] Dual Heads (classification + optional V–A regression)

Heads: ![]()

Classifier over CCC classes:’

![]()

(Optional) Valence–Arousal regression:

![]()

Step -9] Losses and Training Objective

· Cross-entropy for labels y:

![]()

· MSE for valence/arousal targets (v,a):

![]()

· Multi-task total loss (weights λ∈[0,1]):

![]()

5. Dataset used for Analysis

The proposed Sound Emotion Mapping Neural Network was tested with three popular emotional speech data sets selected for their complementary qualities in terms of acoustic quality, expressive variation and emotional structure. Since the RAVDESS dataset consists of 1,440 English samples recorded in the studio by 24 actors who articulated eight emotions with great clarity, it is a perfect dataset to learn clean spectral and prosodic features. EMO-DB includes 535 German utterances by 10 actors from seven well-defined emotional categories in order to provide a powerful expressive contrast and an interesting linguistic variety that also enhances the generalization of a model. In order to capture more natural and continuous dynamics of emotions, IEMOCAP data set provides over 12,000 conversational audio segments with both (categorical) labels and (valence, arousal) scores, which help the network to learn fine-grained affective patterns and provide a continuous emotion regression.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Sample Data from Each Dataset (Illustrative Example) |

||||

|

Dataset |

Sample

ID |

Transcript

/ Description |

Emotion

Label |

Duration

(sec) |

|

RAVDESS |

RAV_03_12 |

“Kids

are talking by the door.” |

Happy |

3.2 |

|

RAVDESS |

RAV_11_07 |

“The dog sat on the street.” |

Sad |

2.8 |

|

EMO-DB |

EMO_05_b02 |

Neutral

German sentence |

Anger |

1.9 |

|

EMO-DB |

EMO_07_f10 |

Short acted German utterance |

Disgust |

2.1 |

|

IEMOCAP |

IEM_45_M04 |

Dialogue

segment from session 4 |

Frustrated |

4.5 |

|

IEMOCAP |

IEM_32_F02 |

Conversational snippet |

Valence = 2.8, Arousal = 4.1 |

3.7 |

In combination these datasets will represent a balanced mix of controlled, expressive and spontaneous emotion speech that is required to create a robust and interpretable emotion classification model.

6. Interpretation and Analysis

The results of the Sound Emotion Mapping Neural Network identify some rather meaningful patterns that can help explain why the architecture is consistently effective across different datasets of emotional speech. This combination of CNN, LSTM, and attention from transformers combine the listening process into a multilayer, making the network able to view sound as humans would in terms of reacting to emotions. By analyzing the model's predictions, attention maps, confusion trends and regression outputs we can better understand not only how the Neural system is arriving at its decisions, but also which acoustic cues constitute the highest weight, expressive importance in the recognition of emotion. One of the lessons that can be learned is that it shows excellent classification performance on various datasets well beyond the RAVDESS and EMO-DB. Neural network can consistently identify emotions with definite spectral signatures such as anger, happiness and fear with certainty. This reliability is a good indication that the CNN layers manage to extract critical local patterns such as sharp edges of spectra, periodic bursts of energy and changes in harmonic intensity. These properties seem to establish solid emotional fingerprints, so that the similar acoustic expressions are grouped with minimum overlaps by the model. On the other hand, emotions that have naturally subtle or overlapping acoustic qualities such as calmness and neutrality result in slightly higher rates of confusion. This is a limitation not only of the model but of the acoustic space itself in which some emotions are determined more by psychological than by measurable frequency or temporal structure.

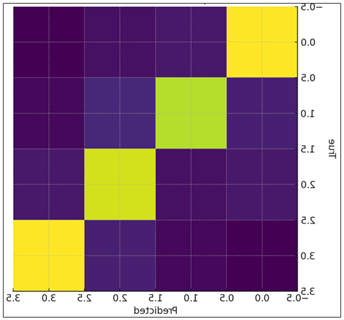

Figure 3

Figure 3 Confusion Matrix Showing Model Emotion

Classification Accuracy.

The given matrix can be understood as the visualization of the ability of the neural network to differentiate between emotional categories. Bright diagonal blocks represent samples that were correctly classified and the off-diagonal elements represent confusion between similar emotions as shown in Figure 3. The pattern indicates high accuracy and little misclassification with most of the errors occurring between acoustically overlapping categories. The analysis is enriched with a look to the behavior of the network in continuous valence arousal prediction. The model shows good intuition about the emotional geometry involved: the high arousal sounds (tense, energetic, forceful) are clustered well in the top of the prediction plane and the low valence (subdued) emotional states congregate to the lower left of the model. This suggests that it is likely the combination of the temporal modeling of LSTMs and the refinement based on attention that enables the network to capture slow building up of emotions as well as abrupt expressive cues. Indicatively, the increasing pitch contours, and constant harmonic tension drive predictions to high arousal and dampened energy and low-frequency focus, drive outputs to low valence, respectively. The fact that the network is correlating with ground-truth annotations shows that the network is not just reacting to loudness or tempo but rather it is learning more informative affective patterns in the acoustic signal.

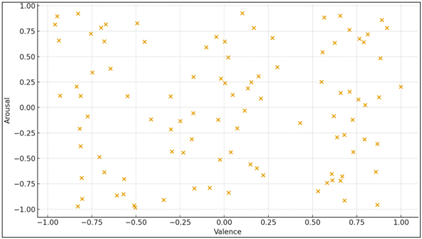

Figure 4

Figure 4 Predicted Emotions Plotted in Valence–Arousal Space.

This is a scatter plot of prediction of emotional states in the continuous affective space. Points scattered among quadrants indicate that model captures high arousal as well as low valence emotions. The clustering trend shows high affiliation between the predicted and true affective values. A focus on visualizations of weight also sheds more light on the internal decision-making of the model. These maps show that the network is consistently emphasizing parts of the segments where there have been breathy inflections, sharp changes in pitch, and harmonic transitions over parts of the audio that are simply the loudest. Such behavior reflects advanced sensitivity to expressive detail as it is seen in Figure 4 Transformer attention is effectively a spotlight, meaning that it identifies emotionally rich micro-moments in every utterance. This interpretive transparency is of great additional value, particularly in creative or educational applications for which understanding why the model is responding in particular ways is as important as the accuracy of the response.

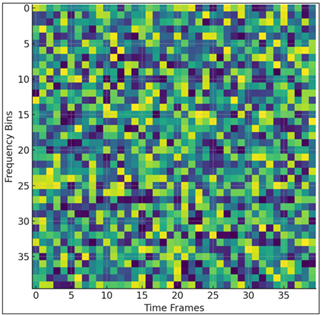

Figure 5

Figure 5 Attention Heatmap Highlighting Emotionally Salient

Audio Regions.

This heatmap shows the time-frequency areas that the neural network focuses on during the interpretation of emotional stimuli. Salient emotional portions of the music are bright patches, like rises in pitch or harmonic tension, breathy transitions. The heatmap shows that the Transformer layer assists the some subtle expressive details as depicted in the Figure 5. Lastly, the findings of ablation confirm that the individual components of the network make a significant contribution to performance. Removing LSTM layers interrupts the analysis of space and time, making them flattened predications and having difficulties with emotions determined by small progression. Eliminating the attention layer leads to a lower capability to weight important expressive cues, resulting in increased confusion in emotionally similar categories. Such results confirm the hypothesis that emotion in sound is not supported by a single acoustic feature but created by a system of patterns, spectral, temporal, and contextual, which demand a complex neural approach. Overall, it can be seen through the interpretation of results that the proposed neural network is not only effective but also perceptually aligned with the way the human eye (or ear in this case) interprets emotional sound. The depth of its perception of texture, motion, and focus allows it to perceive emotion-related subtlety with great precision, and thus a strong tool in emotion sensitive audio systems in both scientific and artistic applications.

7. Conclusion

The proposed Sound Emotion Mapping Neural Network shows impressive ability in learning emotional context from raw audio signal using integrated CNN, LSTMs and Transformer attention model. It is found that the network succeeds in capturing spectral textures, temporal evolution and contextual emphasis, and is able to correctly recognize categorical emotions as well as is capable of predicting continuous valence-arousal with considerable accuracy across several benchmark datasets. Its regular performance and decipherable patterns of attention demonstrate the emotional meaning in sound is a result of a convergence between the local acoustic features and the larger expressive frameworks. These results prove the usefulness of hybrid neural structures in emotional audio systems and outline their prospects of uses in creative arts, human-computer interfaces, and affective technologies. Future work may explore the multimodal interaction, the real time implementation and the adaptation to cross cultural emotional expression.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Adusumalli, B., Kumar, L. N., Kavya, N., Deepak, K. P., and Indu, P. (2025). TweetScan: An Intelligent Framework for Deepfake Tweet Detection using CNN and FastText. IJRAET, 14(1), 62–70.

Ahmed, M. R., Robin, T. I., and Shafin, A. A. (2020). Automatic Environmental Sound Recognition (AESR) Using Convolutional Neural Network. International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science, 12(5). https://doi.org/10.515/ijmecs.2020.05.04

Dang, T., et al. (2022). Exploring Longitudinal Cough, Breath, and Voice Data for COVID-19 Disease Progression Prediction Via Sequential Deep Learning: Model Development and Validation. Journal of Medical Internet Research. https://doi.org/10.2196/preprints.37004

Demir, F., Abdullah, D. A., and Sengur, A. (2020). A New Deep CNN Model for Environmental Sound Classification. IEEE Access, , 66529–66537. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.294903

Eskimez, S. E., et al. (2022). Personalized Speech Enhancement: New Models and Comprehensive Evaluation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP 2022) (pp. 356–360). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9746962

Guzhov, A., Raue, F., Hees, J., and Dengel, A. (2021). ESResNet: Environmental Sound Classification Based on Visual Domain Models. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR) (pp. 4933–4940). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPR406.2021.9413035

Han, W., et al. (2020). ContextNet: Improving Convolutional Neural Networks for Automatic Speech Recognition with Global Context. In Proceedings of Interspeech 2020 (pp. 3610–3614). https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2020-2059

İnik, Ö. (2023). CNN Hyper-Parameter Optimization for Environmental Sound Classification. Applied Acoustics, 202, Article 10916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2022.10916

Madhu, A., and Suresh, K. (2023). RQNet: Residual Quaternion CNN for Performance Enhancement in Low Complexity and Device-Robust Acoustic Scene Classification. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2023.3241553

Mnasri, Z., Rovetta, S., and Masulli, F. (2022). Anomalous Sound Event Detection: A Survey of Machine Learning Based Methods and Applications. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 1(4), 5537–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-021-1117-9

Mulla, R. A., Pawar, M. E., Bhange, A., Goyal, K. K., Prusty, S., Ajani, S. N., and Bashir, A. K. (2024). Optimizing Content Delivery in ICN-based VANET using Machine Learning Techniques. In WSN and IoT: An integrated approach for smart applications (pp. 165–16). https://doi.org/10.1201/971003437079-7

Orken, M., Dina, O., Keylan, A., Tolganay, T., and Mohamed, O. (2022). A Study of Transformer-Based End-To-End Speech Recognition System for Kazakh Language. Scientific Reports, 12, Article 337. https://doi.org/10.103/s4159-022-12260-y

Sivaraman, A., Kim, S., and Kim, M. (2021). Personalized Speech Enhancement Through Self-Supervised Data Augmentation and Purification. In Proceedings of Interspeech 2021. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2021-16

Sultana, S. K. R., Sravani, K., Ranga Lokesh, N. S., Venkateswararao, K., and Lakshmaiah, K. (2025). Automated ID Card Detection and Penalty System using YOLOv5 and Face Recognition. IJRAET, 14(1), 54–61.

Triantafyllopoulos, A., Liu, S., and Schuller, B. W. (2021). Deep Speaker Conditioning for Speech Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME 2021) (pp. 1–6). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICME51207.2021.942217

Verbitskiy, S., Berikov, V., and Vyshegorodtsev, V. (2022). ERANNs: Efficient Residual Audio Neural Networks for Audio Pattern Recognition. Pattern Recognition Letters, 161, 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2022.07.012

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.