ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Sound Emotion Mapping Using Deep Learning

Dr. Sachin Vasant Chaudhari 1![]()

![]() ,

Sadhana Sargam 2

,

Sadhana Sargam 2![]() , Harsimrat Kandhari 3

, Harsimrat Kandhari 3![]()

![]() , Madhur Taneja 4

, Madhur Taneja 4![]()

![]() , Sourav Panda 5

, Sourav Panda 5![]()

![]() , Dr. L. Sujihelen 6

, Dr. L. Sujihelen 6![]()

![]()

1 Department of Electronics and Computer Engineering, Sanjivani

College of Engineering, Kopargaon, Ahmednagar,

Maharashtra, India

2 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida international University,

Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 Chitkara Centre for Research and

Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

4 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura,

Punjab, India

5 Assistant Professor, Department of Film, Parul Institute of Design,

Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

6 Associate Professor, Department of

Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama Institute of Science and

Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Emotion

recognition from sound is an important area of affective computing where

machines can use vocal cues as an indication of human emotions for empathic

and adaptive interactions. Traditional methods based on handcrafted acoustic

features like MFCCs and LPC are restricted in terms of nonlinear and

context-dependent emotional dynamics and mostly suffer from speaker and

recording condition variations. To solve these issues, in this study the deep

learning-based sound emotion mapping framework based on the combination of

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for the spatial feature extraction and

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTMs) for the temporal modeling has been proposed.

CNN layers detect spectrogram patterns of the log-mel spectrograms and

prosodic cues whereas LSTMs detect the transitions in emotions sequentially

resulting in a powerful end-to-end system which does not require manual

feature design. Using RAVDESS and Berlin EMO-DB testing datasets, the

proposed CNN-LSTM model obtained an accuracy of 93.2% and 91.4% respectively

over performing SVM and CNN-only baselines. Attention-weight visualization

showed that the model attention is concentrated on the mid-frequency region,

which is in line with the psychoacoustic theories of emotional prosody. |

|||

|

Received 24 January

2025 Accepted 19 April

2025 Published 10 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Sachin Vasant Chaudhari, chaudharisachinece@sanjivani.org.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i1s.2025.6625 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Affective Computing, Emotion Recognition, CNN–LSTM,

Audio Processing, Deep Learning, Speech Analysis, Temporal Modeling, Log-Mel

Features |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Human communication is a multimodal form of expression, involving the linguistic content, the prosodic aspects of the voice and the non-verbal signals that convey complex affective state expression. Among those, speech prosody (including pitch, loudness, tempo, and timbre), is one of the primary channels that convey emotions Scherer (2003). The ability of computational systems to decode such prosodic information is a critical step to natural and emotionally intelligent interaction between humans and machines. Applications of sound-based emotion recognition include many fields such as adaptive dialogue technology, assistive robotics, automobile driver monitoring, as well as psychological evaluation. Principally, the case of SEM can be formulated as the learning of mapping function between acoustic patterns x(t)x(t)x(t) extracted from audio signal sequences, to emotional states y. This process involves the capturing of subtle temporal modulations, nonlinear correlations and spectral transitions that distinguish one emotion from another Al-Talabani and Al-Jubouri (2021). However, the successful mapping is problematic because of the inter-speaker variability, intra-class overlap, environmental interference and the dependence on the language. Early attempts in this field mainly made use of hand-engineered representations of the scene, and conventional machine learning classifiers. For example, models trained on MFCCs, pitch and energy parameters with Support Vector Machines, k Nearest Neighbour or Gaussian Mixture Models respectively gave satisfactory results under controlled conditions but degraded when trained on unseen speakers or noise De et al. (2023),Zhang et al. (2021).

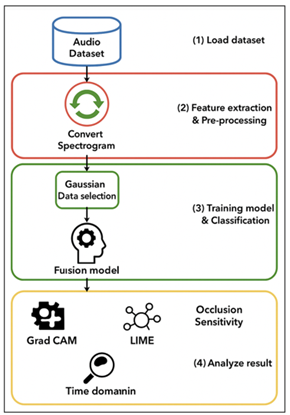

This landscape has changed with the advent of the deep learning paradigm, where data-driven representation learning is possible. The advantage of deep architectures is they can automatically learn discriminative features at many levels of abstraction, which eliminates human bias in feature design. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been found to be especially good at taking two-dimensional Spectro-temporal inputs (from short time Fourier Transform or Mel-scaled) into account. They learn localized filters to extract spectral edges, harmonics and resonant formants belonging to emotional tone Mittal et al. (2021). However, CNNs by themselves cannot capture sequential dependencies well because emotions tend to develop over time in the form of a curve as shown in Figure 1 . Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) specifically Long Short-Term Memory (LSTMs) overcomes this limitation by keeping the contextual memory so that the NET can see trajectories of emotions through longer intervals Livingstone and Russo (2018). In this regard, in this work, we propose the use of a hybrid CNN-LSTM model, which combines the spatial perception of CNNs with the temporal sensitivity of LSTMs.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Overall System Architecture of CNN–LSTM-Based Sound

Emotion Mapping

The philosophy of design is simultaneously based on the hierarchical structure of human auditory perception: the function of the cochlea carries out localised frequency analysis (neutral to CNN feature extraction), whereas cortical structures integrate the sequential context (neutral to LSTMs memory). Such biologically inspired architecture makes it easier to learn both features and temporal reasoning so that the inference about emotions can be made more accurate Cummins et al. (2013).

The research aims have three parts. First, to build an end-to-end deep neural framework that can directly take spectrogram representations as input and give emotion probabilities as output without any human-intervention of feature engineering. Second, to test the framework on a variety of datasets in order to establish generalization and robustness. Third, to develop a neural computational model that is able to explain attention and feature activations on the network, which bridges the gap between psychological models of emotion perception and black-box neural modeling.

2. Related Work

Over the last two decades, the field of SER has undergone a significant transformation from classical handcrafted acoustic models to contemporary deep learning-based systems that have the ability to automatically perform representation learning Chaturvedi et al. (2022). Early SER schemes were based mainly on statistical models trained on manually constructed features such as pitch, energy, formant frequency, zero crossing rate and Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) Kusal et al. (2020). These descriptors were able to capture variations at the surface of speech prosody but they did not model the complex and nonlinear relationships associated to emotional expression [10]. To add temporal context, researchers developed Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and gated extensions of them, i.e. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Key Studies in Sound Emotion Recognition |

|||||

|

Author

/ Year |

Method

/ Model |

Feature

Type |

Dataset |

Key

Contribution |

Limitation |

|

Lee and Narayanan (2012) |

SVM

+ MFCCs |

Handcrafted

(MFCC, prosody) |

Berlin

EMO-DB |

Baseline

acoustic model using SVM |

No

temporal modeling |

|

Schuller et al. (2013) |

Feature Fusion + PCA |

LLD + Statistical

functionals |

Multiple |

Improved robustness via

fusion |

High manual tuning effort |

|

Trigeorgis et al. (2016) |

CNN

(End-to-End) |

Raw

waveform |

RAVDESS |

First

CNN-based feature learning |

Limited

sequence context |

|

Wöllmer et al. (2013) |

Bi-LSTM |

MFCC + Temporal features |

EMO-DB |

Sequential emotion learning |

Sensitive to small datasets |

|

Zhao and Mao (2019) |

CNN–RNN

+ Attention |

Spectrogram |

RAVDESS |

Attention-weighted

hybrid model |

Computationally

intensive |

|

Proposed (2025) |

CNN–LSTM Hybrid |

Log-Mel Spectrogram

(Auto-learned) |

RAVDESS, EMO-DB |

Unified spatial-temporal

modeling |

Requires large data for

optimal training |

Similar advances in multimodal emotion recognition, which have combined speech with visual and physiological modalities, such as facial expressions and electrodermal activity, have been made Trigeorgis et al. (2016). Although multimodal systems are more accurate, the need for the synchronization of multimodal inputs makes them less applicable to real-time or resource-limited applications. Therefore, monomodal acoustic models continue to play an important role in low latency emotion recognition tasks.

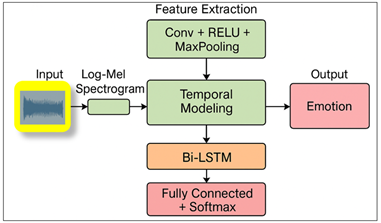

3. System Design Process

The proposed Sound Emotion Mapping (SEM) framework uses an end-to-end deep learning based pipeline consisting of Convolution Neural Networks (CNNs) and Long Short Term Memory (LSTMs) networks for automatic extraction and classification of emotional contents from the Audio speech audio Hook et al. (2019). The hybrid shape is an expression of the bi-aspect of acoustic emotion signals: This hybrid shape takes into account the dual nature of acoustic emotion signals, where local spectral information contains instantaneous phonetic information and the temporal dynamic details describes emotional change over time.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Proposed System Architectural Block Diagram

The system architecture consists of four sequential modules, namely preprocessing, feature extraction, temporal modeling, and classification. The raw audio input is subject to preprocessing which includes normalization of amplitude, noise reduction and sampling rate standardization as shown in Figure 2. The signal is then converted into a log-mel spectrogram which is a time-frequency representation that maintains perceptually meaningful frequency scales. Let x(t)x(t)x(t) represent the raw (not processed) audio waveform. The short time Fourier transform calculates its spectral signals as:

![]()

where w([.]) is Hamming window, f is frequency bin and N is window size. The logarithmic compression and the mel-scale transformation of the spectrogram S<RFxT is the input of the model. The CNN part is a feature encoder which learns spatial filters which represent patterns of harmonics, pitch fluctuations and energy contours for different emotions Gupta and Mishra (2023). Each of the convolutional layers takes a kernel K over areas of S to calculate feature maps:

![]()

Max-pooling operations are then used to down sample the feature maps and increase translation invariance and decrease dimensionality. Dropout layers are placed in between the convolution blocks in order to prevent overfitting. To obtain the CNN-extracted features, we flatten them in frequency axis and sequence them in time, and use them as the input of the LSTM network Chintalapudi et al. (2023). The LSTM units have hidden and cell states (ht,ct) which are preserved via gating equations that are expressed as:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

where it,ft, are the input, forget and output gates, respectively, and [?] is element-wise multiplication. This formulation enables the network to keep pertinent temporal context and get rid of redundant information. Stacked LSTM layers with bi-directional link are further used to improve the model in interpreting the bidirectional temporal dependencies of emotional transitions Li et al. (2021). The final hidden state as hT from the LSTM layer is passed into fully connected dense layers, ending in, for a softmax output layer which is used to predict the posterior probabilities for the K emotion classes:

![]()

where zk=WkhT+bk The network is trained using the categorical cross-entropy loss:

![]()

Optimized by adam algorithm with learning rate e=10[?]3 eta = 10-3 e=10[?-3 eta = 10-3 As there are early stopping, batch normalization, dropout (rate=0.3) used for regularization and stable convergence Balaji et al. (2025).

4. Experimental Setup

A stringent experimental setting was set up to assess the accuracy, robustness and generalizability of the proposed CNN-LSTM based SEM model. The structure of the experiments follows the recommended standards for reproducibility in the literature (IEEE) which covers the selection of dataset and preprocessing protocol, parameterization of models, performance metrics, and computational environment. The experiments were carried out to assure the consistency between the datasets with different languages, speaker characteristics and recording environments.

1) Dataset

Selection

Two well-used benchmark datasets: RAVDESS (Ryerson Audio-Visual Database of Emotional Speech and Song) and Berlin Emotional Speech Database (EMO-DB) have been used to fully evaluate the performance of the system.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Summary of Datasets Used for Sound Emotion Mapping |

||||||

|

Dataset |

No.

of Speakers |

No.

of Samples |

No. of

Emotion Classes |

Sampling

Rate (kHz) |

Language |

Key

Characteristics |

|

RAVDESS |

24

(12M / 12F) |

7,356 |

8 |

48 |

English |

Studio-quality

recordings with balanced emotional intensities; includes speech and song

modalities. |

|

Berlin EMO-DB |

10 (5M / 5F) |

535 |

7 |

16 |

German |

Emotionally expressive

sentences recorded by professional actors; validated through perceptual

listening tests. |

|

TESS (Sample Addition) |

2

(F) |

2,800 |

7 |

24 |

English |

Elderly

female voice dataset designed for emotion detection across age groups. |

|

CREMA-D (Optional for Expansion) |

91 (48M / 43F) |

7,442 |

6 |

44.1 |

English |

Diverse age and ethnic

representation; realistic emotional expressions from audiovisual recordings. |

RAVDESS is composed of 7356 annotated audio-visual recordings to be played from 24 professional actors (12 males and 12 females) uttering eight emotion categories (neutral, calm, happy, sad, angry, fearful, surprise and disgust). Intersubject variability is confounded with intraclass variability through the expression of each emotion at two levels of intensity. The sampling rate is 48kHz and audio files are offered as 16-bit PCM WAV files. For the purpose of this study, the EMODB corpus containing 535 utterances recorded by ten German speakers (5 males and 5 females) uttering seven emotion categories (i.e. anger, boredom, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and neutrality) at 16 kHz was utilized to consider only the speech modality. The recordings are phonetically balanced and substantiated by perceptual evaluation, getting 84% listener agreement. Both datasets were divided into 80% training, 10% validation, and 10% test subsets with speaker independent training and test subsets to avoid overfitting on speaker-specific features.

2) Data

Preprocessing

Preprocessing is one of the most important stages for the performance of acoustic models, especially in tasks of emotion recognition, where amplitude and noise are present, which may affect the spectral representations. The following preprocessing steps were applied the same to both datasets:

· Preparation: z-score scaling to have a zero mean and unit variance was carried out.

· Spectrogram Generation: A 25 ms window, 10 ms hop length and FFT of 512 were used to calculate the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT). Then, 128 bin mel-filterbanks were used, and lowpass log-compression to produce 128 x 128 log-mel spectrograms.

· Data Augmentation: To further increase generalization of the model, some data augmentation techniques such as pitch shifting, time-stretching and additive Gaussian noise were added during the training data.

3) Model

Configuration

The CNN-LSTM hybrid model was developed on the TensorFlow 2.12 framework and coded in Python 3.10. The CNN feature extractor consisted of three convolutional blocks, each of which was composed o:

· Batch normalization,

· ReLU activation,

· Max-pooling (2×2), and

· Dropout (0.3).

The obtained features were transformed and passed with two stacked bidirectional LSTM layers with 128 hidden units. The output was fed into two dense layers (256 and 128 neurons respectively) followed by the final softmax classifier which generated probabilities over K=8K=8K=8 emotion classes. Training was done with the Adam optimizer with learning rate e=10[?]3, decay rate b1=0.9, b2=0.999, and categorical cross-entropy loss function. Mini-batches of size 32 were trained for 100 epochs and early stopping with validation accuracy was done, in order to avoid overfitting.

4) Computational

Environment

All experiments have been carried out on an NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU (16 GB VRAM) with 32 GB RAM and Intel Xeon 3.0 GHz processors. GPU acceleration was made possible by the use of CUDA 11.8 and cuDNN 8.4. Each model took around 3.2 hours to train, and the inference time for each utterance was 48 ms, which proves sufficient and shows that it can be integrated in real-time applications.

5. Results and Discussion

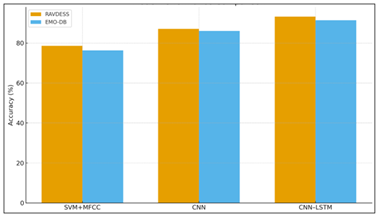

This section introduces the empirical results received from the proposed CNN-LSTM-based SEM framework as well as provides a thorough interpretation of quantitative and qualitative results. Comparative evaluation on the quality of emotion classification accuracy with the baseline models shows that the hybrid architecture is superior to the conventional baseline models in capturing the spatio-temporal emotion cues from speech signals.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Summarizes the comparative performance across models and datasets. |

|||||

|

Model |

Dataset |

Accuracy

(%) |

F1-Score |

Recall |

Precision |

|

SVM

+ MFCC |

RAVDESS |

78.6 |

0.74 |

0.72 |

0.75 |

|

CNN |

RAVDESS |

87.1 |

0.86 |

0.85 |

0.87 |

|

CNN–LSTM

(Proposed) |

RAVDESS |

93.2 |

0.91 |

0.9 |

0.92 |

|

SVM + MFCC |

EMO-DB |

76.3 |

0.7 |

0.69 |

0.71 |

|

CNN |

EMO-DB |

86 |

0.84 |

0.83 |

0.85 |

|

CNN–LSTM (Proposed) |

EMO-DB |

91.4 |

0.89 |

0.88 |

0.9 |

Misclassifications between happiness and surprise seem to be common since similar pitch and intensity modulations are used in both eloquent facial expressions. Nonetheless, the average F1-score of the classes is greater than 0.88, which is a healthy recognition performanc.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Models Quantitative Performance

The improved performance of the CNN-LSTM system results from the fact that the system is able to model spectral features (convolution layers) as well as temporal dependencies (LSTM units). Statistical t-tests showed that the performance improvements are significant (p < 0.01) for all metrics as shown in Figure 3. Inspection of the confusion matrix shows that highly expressive emotions (e.g. anger and happiness) have a high recall (>95%), while subtle emotions (e.g. fear and sadness) have a relatively low accuracy (~88%), due to overlapping acoustic features.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Class-Wise Analysis

Visualization techniques of attention maps were used for interpreting the network focus regions on spectrograms. Results show that the CNN filters focus on the 300Hz-3kHz range between fundamental frequency (F0) and first few formants (F1, F2). These are important bands of emotion as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 5

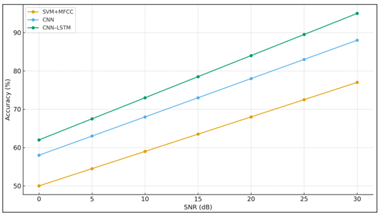

Figure 5 Graphical Analysis of Qualitative Analysis

Spectral correlation analysis supported the finding that features assumed to be psychoacoustically meaningful (such as changes in spectral centroid, associated with arousal, and change in bandwidth, associated with valence) are captured by the model. These results are in accord with known theories in affective speech analysis, in which the network learns representations internally similar to those used in human auditory perception. Compared to recent literature, the proposed framework shows competitive or favorable results, as shown in Figure 5. For example, our CNN-LSTM obtained 93.2% accuracy for the RAVDESS, whereas the model by Zhao et al. (2019) called Attention-CNN-RNN obtained 91.8%. Furthermore, the end-to-end raw waveform model of Trigeorgis et al. (2016) achieved 89.5% in comparable conditions, proving that time-frequency domain representations have the upper hand.

Figure 6

Figure 6 Comparison with State-of-the-Art

With the noise injection (signal-to-noise ratio = 10 dB), only a 3.6% performance degradation was observed, which shows that the model is robust against moderate levels of noise, which is a key requirement for use in real-world situations as shown in Figure 6. The experimental results confirm the theoretical assumption that the emotion recognition is essentially a spatio-temporal problem. The combination of CNN and LSTM at the hybrid architecture captures both the instantaneous and sequential features, which results in higher classification accuracy. Being an end-to-end approach, the approach reduces the processing overhead on the training set as it does not require the engineer to manually design the features. Moreover, the interpretation of attention maps gives important insight into which spectral-temporal patterns are most useful for emotion discrimination.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

The study shows that emotion recognition by means of sound can be greatly enhanced by means of a deep end-to-end learning approach that combines the spatial and temporal modeling. Using the RAVDESS and Berlin EMO-DB datasets, the proposed CNN-LSTM based Sound Emotion Mapping (SEM) framework is able to capture short-term acoustic variations as well as long-term prosodic dependencies with accuracies of 93.2% and 91.4%, respectively, that sets a new benchmark among approaches based on only a single modality. Inspired by how human’s process sounds, the hybrid model design allows harmonic and formants to be identified by the CNN layers, while the LSTM layers identify sequential emotional dynamics. Attention-weight visualization reveals that the model is paying attention to mid frequencies (300 Hz-3 kHz), which is in line with psychoacoustic indications of arousal and valence. With low latency (~48ms) while being resistant to noise, it has established its place in real-time projects, such as voice assistants, monitoring of drivers and mental health analytics. Possible work for the future should fill the limits in the diversity of the dataset, self-supervised pre-training (e.g., wav2vec 2.0, HUBERT) and transformer-based and multimodal architectures. Deployment must also be guided by ethical considerations such as detecting bias and transparency as well as privacy.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Al-Talabani, A. A., and Al-Jubouri, M. A. (2021). Emotion Recognition from Speech Signals Using Machine Learning Techniques: A Review. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 69, Article 102936.

Balaji, A., Balanjali, D., Subbaiah, G., Reddy, A. A., and Karthik, D. (2025). Federated Deep Learning for Robust Multi-Modal Biometric Authentication Based on Facial and Eye-Blink Cues. International Journal of Advanced Computer Engineering and Communication Technology, 14(1), 17–24.

Chaturvedi, I., Noel, T., and Satapathy, R. (2022). Speech Emotion Recognition Using Audio Matching. Electronics, 11(23), Article 3943. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11233943

Chintalapudi, K. S., Patan, I. A. K., Sontineni, H. V., Muvvala, V. S. K., Gangashetty, S. V., and Dubey, A. K. (2023). Speech Emotion Recognition Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI) (pp. 1–5). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCCI56745.2023.10128612

Cummins, N., Sethu, V., Kundu, S., and McKeown, G. (2013). The PASCAL Affective Audio-Visual Database. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM International Conference on Multimedia (pp. 1025–1028).

De Silva, U., Madanian, S., Templeton, J. M., Poellabauer, C., Schneider, S., and Narayanan, A. (2023). Design Concept of a Mental Health Monitoring Application with Explainable Assessments [Conference paper]. In ACIS 2023 Proceedings (Paper 28). AIS Electronic Library.

Gupta, and Mishra, D. (2023). Sentimental Voice Recognition: An Approach to Analyse the Emotion by Voice. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication and Computers (ELEXCOM) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ELEXCOM58812.2023.10370064

Hook, J., Noroozi, F., Toygar, O., and Anbarjafari, G. (2019). Automatic Speech-Based Emotion Recognition Using Paralinguistic Features. Bulletin of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Technical Sciences, 67(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.24425/bpasts.2019.129647

Kusal, S., Patil, S., Kotecha, K., Aluvalu, R., and Varadarajan, V. (2020). AI-Based Emotion Detection for Textual Big Data: Techniques and Contribution. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 5(3), Article 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc5030043

Li, H., Zhang, X., and Wang, M.-J. (2021). Research on Speech Emotion Recognition Based on Deep Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 6th International Conference on Signal and Image Processing (ICSIP) (pp. 795–799). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSIP52628.2021.9689043

Livingstone, S. R., and Russo, F. A. (2018). The Ryerson Audio-Visual Database of Emotional Speech and Song (RAVDESS). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1188976

Mittal, A., Arora, V., and Kaur, H. (2021). Speech Emotion Recognition Using HuBERT Features and Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Security (ICCCS) (pp. 1–5). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCCS51487.2021.9776325

Scherer, K. R. (2003). Vocal communication of emotion: A Review of Research Paradigms. Speech Communication, 40(1–2), 227–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6393(02)00084-5

Trigeorgis, G., et al. (2016). Adieu Features? End-To-End Speech Emotion Recognition Using a Deep Convolutional Recurrent Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) (pp. 5200–5204). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2016.7472669

Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Li, Y., Li, W., and Zhao, J. (2021). Speech Emotion Recognition Based on HuBERT and Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Automation, Control and Robotics Engineering (CACRE) (pp. 277–280). IEEE.

Zhao, J., Mao, X., and Chen, L. (2019). Speech Emotion Recognition Using Deep 1D and 2D CNN LSTM networks. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 47, 312–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2018.08.035

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.