ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

OPPORTUNISTIC DEXTERITY OR FLEXIBLE INTELLIGENCE?: CONTEMPLATING THE NATURE OF AMBIVALENCE INTRINSIC TO TRICKSTER ARCHETYPE FIGURES IN TRIBAL FOLKTALES OF JHARKHAND

M. Ramakrishnan 1![]()

![]() ,

Shalini Pallavi 2

,

Shalini Pallavi 2![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor of Folklore, Department of Anthropology & Tribal Studies, Central

University of Jharkhand, Cheri-Manatu, Ranchi

2 Research

Scholar, Department of Anthropology & Tribal Studies, Central University of

Jharkhand, Cheri-Manatu, Ranchi

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Trickster figures are absolutely universal and they

are creations of human collective unconsciousness. And advantageously as well

disadvantageously they are not defined (confined) by any single

characteristics as they are multifaceted entities, multiform beings and

polytropos, with the accumulation of different qualities/features (such as

‘astuteness’, ‘ambivalence’, ‘wit’, ‘clever’, ‘cunning’, ‘tricky’, ‘creative

falsehood’, ‘deceitful’ or ‘camouflage’, ‘clown’, ‘coward’, ‘cheat’,

‘humorous’, ‘brave’, etc.) and different forms (gods, demons, humans,

animals), depending on the nature and requirement of the narrative

programmes. Apart from being the fictional archfigures found in world

mythology, folkloric materials and popular culture, the everyday social life

of people is filled with the experiences of real tricksters, socially

recognized antics of persons who enjoy mixed attributes of cleverness (i.e.,

good and bad), complementary to the logical rationality and being part of the

periphery of their communities and not outside of the communities. Unlike

mythological tricksters who are gods, demons, spirits and other supernatural

beings, some of them are even known for having voracious appetites for food

and bodily pleasure apart from being shape-shifters, rebellious and supreme

boundary-crossers, their counterparts in folktales are simple,

comprehensible, deliberate violators of social rules and norms, and cultural

as well natural. A vast amount of trickster folktales is available in almost

all languages across India. However, this study picks a few folktales from

the tribal communities of Jharkhand, and the ‘tribal folktales’ is used as a

category, a unit for analysis or a semiosphere to investigate the nature and

interconnectedness of various elements associated with the trickster

folktales. Grouped under four themes based on the actions of the protagonists

or antagonists, this study proceeds to construct the nature and availability

of oxymoronic figures as fundamental interdependent elements of these tales.

This study reveals that the tribal tales have effectively utilized trickster

characters to project the concept of altruism, along with the reflection of

local culture and their critical interventions. It also highlights the facts

that the trickster figures in these tales bring together two opposite worlds

for different purposes through border-crossing which is a common phenomenon

as far as the tribal trickster folktales are concerned, and it also reflects

their worldview of coexistence attitude and perceiving them as an integral

part of the ecosystem. Further, this study implies an essential point that

the tricksters found in these tribal folktales perform as semiotic generators

who mediate between opposites to allow a kind of cultural articulation of

different cultural relationships, evaluate their contradictions and renew

their moral and ethical values which are essential for the constitution and

dissemination of their behaviour. Finally, this study promises to draw a

brief sketch of the nature of tricksters and their social function and also

unfolds the reason for the speculation that the tricksters are not enjoying

heroic admiration and esteem despite their marvellous and altruistic heroic

deeds. |

|||

|

Received 11 September 2023 Accepted 30 October 2023 Published 03 November 2023 Corresponding Author M.

Ramakrishnan, ilakkiyameen@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i2.2023.662 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Trickster, Trickery, Archetype, Problem-Solving,

Folk Humour, Conceptual Structure |

|||

With the help of the symbol of negation, thinking frees itself from the restrictions of repression” Freud (1950): 438–9

Since a boundary is a necessary part

of a semiosphere, a semiosphere needs “non-organized,” external surroundings;

and if the latter are absent, it constructs them itself. Culture creates not

only its own internal organization but also its own type of external

disorganization. Antiquity constructed its “barbarians,” and “consciousness”

constructed the “subconscious”

Juri Lotman (1989):48, cf. Gramigna

(2022):143.

Laughter has the remarkable power of

making an object come up close, of drawing it into a zone of crude contact

where one can finger it familiarly on all sides, turn it upside down, inside

out, peer at it from above and below, break open its external shell, look into

its center, doubt it, take it apart, dismember it, lay it bare and expose it,

examine it freely and experiment with it.... As it draws an object to itself

and makes it familiar, laughter delivers the object into the fearless hands of

investigative experiment-both scientific and artistic-and into the hands of

free experimental fantasy. Bakhtin

(1981):23

1. Introduction

When the

crow appears as a trickster figure in Sylvia Moore’s “A Trickster Tale about

Integrating Indigenous Knowledge in University-based Programs” (2012), it is

not an isolated event and uncommon happening, or at least an example of an

exception, since application of folklore is not a new phenomenon, rather it is

something that can be found everywhere and in all societies. However, from this

article, we understand how the ‘trickster space’ is becoming accessible by

turning the story inside out, and the archetype figure of the crow facilitates

the tricksters’ space where two different but conflicting traditions of world

views can come together for learning purposes. That is, the role of folktale,

or its elements, cannot be considered irrelevant, or the form is obsolete, but

its contemporary relevance for society is being constantly proved for various

reasons. Folktale is a simple and common narrative form within the oral

tradition and it is the base structure for all the modern and complex narrative

structures. It appears as a frozen form, but it is evolving and even absorbing

elements from the present. Further, as it is closer to thinking and spontaneous

in terms of its production, the formation of versions is an inherent quality of

folktale. However, it never misses in its objective of conveying its message to

the designated audience, who need not be children, which means, it has ample

scope that the adults and elderly can also learn from it. The conceptual

structure or concepts are being communicated or transmitted to the present

society for the purpose of future generations through narrativization which is

an essential process of the creation of folktales. Folktales have enormous

roles to play in the life of people of different ages, particularly, for example,

they contribute greatly to child development by stimulating and enhancing their

imaginative and cognitive skills. Folktale helps them to acquire a certain

amount of knowledge about various living and non-living objects and their

origins along with the learning of human values (such as honesty, respect,

love, friendship, helping, appreciation, etc.) and some abstract concepts.

While shaping their identity and making them realize their own position, the

folk tale helps them to practice problem-solving which will help them to

overcome future issues. So, it may be said that as much children are exposed to

folktales, that can make them more responsible and objective-oriented. The

sugar-coated, having enjoyable and amusing elements, simplicity of form as well

as linear storytelling or presentation, folktale fulfils its task of imbibing a

kind of knowledge system in the mind of children. Further, a vast amount of

vocabulary can be added to the children’s repertoire for future use and moral

and life lessons are taught to the children. Further, the children will be

exposed to sources of cultural information as well as various forms of

discourse.

Despite being understood as a source of

entertainment, the folktale form serves as a source of information for millions

and millions of unlettered people around the world who have orality as the

chief means of knowledge transference. Sarita Sahay mentions that “the

folktales of different regions represent the thoughts, ideas, mental states,

traditions, manners and customs and even wit and wisdom of the people of that

region”. The folk aesthetics can be best understood mainly from folktales and

folktales are good treasure for studying language use particularly the use of

figures of speech such as analogy, simile, metaphor and metonymy. Storytelling

is not a mechanical process and although it is extemporary, the socio-cultural

and economic condition of the storyteller is found subtly mentioned in the

story texts which can be studied for different purposes. It means that while

reflecting on the past the folktales have insight for the future as well as

they absorb and react to the present. The state of Jharkhand is undoubtedly

rich by being a treasure of folklore and other cultural creative expressions

which are the cumulative contribution of both tribal and non-tribal communities

living in the state whose linguistic and cultural plurality solicits

multidisciplinary studies. Apart from having an attractive and cascading

landscape, and sharing borders with West Bengal, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar

Chhattisgarh, and Odisha, the state of Jharkhand is having every element to

significantly enhance among its different linguistic and cultural groups a kind

of mutual interactiveness which ensures a harmonious atmosphere that promotes

reciprocal and coexistence attitude among the masses. However, as Jharkhand is

declared a tribal state for the development, promotion and preservation of

language, culture and folklife of both the major tribal communities such as

Santhals, Oraons, Mundas and Hos as well as minor tribes such as Asurs, Baigas,

Banjaras, Bathudis, Bedias, Binjhias, Birhors, Birjias, Cheros, Chick-Baraiks,

Gonds, Goraits, Karmalis, Kharwars, Khonds, Kisans, Koras, Korwas, Lohras,

Mahlis, Mal-Paharias, Parhaiyas, Sauria-Paharias, Savars, Bhumijs, Kols and

Kanwars, this article intends to highlight the cultural specificity in handling

universal concepts, ideas and notions. The tales selected for this study have

trickery as a major component or common motif and instead of moving on the line

of projecting the trickster merely as an archetypical figure, it is established

here that trickery as a complex phenomenon or technique is used for the

problem-solving purpose in these tales which is an important cognitive task

that requires the participation of multiple concepts and notions on the one

hand and not the commonsensical but logical framework of the whole issue on the

other hand. Some of the tribal folktales of Santhal and Oraon communities,

available in print Sarita Sahay (2013), Bompas (1909), Grignard (2017) have been found useful in this study.

Trickster tales are found almost in every

society and thus, a good number of studies can also be carried out, among them

many of the studies are experimental or test-oriented. Some of the studies are: Jarvey & Anne (2003) (“Teaching Trickster Tales: A Comparison of Instructional Approaches in

Composition”); Radin (1956) (The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology); Kraus (1999) (Folktale Themes and Activities for Children, Vol.2: Trickster and

Transformation Tales); C. Jung (1956) (“On the Psychology of the Trickster Figure”); Hyde (1998) (Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and Art); Derry (2014) (“Tricksters”); Terrell (1995) (From Anansi to Zomo: Trickster Tales in the

Classroom); Edmonds (1966). (Trickster Tales); Gleeson (1992). (Anansi); Mayo (1993). (Meet tricky coyote!); Yep (1993). (The Man Who Tricked a Ghost); Robinson (1982) (Raven the Trickster); Danišová (2022) (“Notes on the Trickster as a Literary Character in Archnarratives: A

Brief Initial Analysis”); Gregory (2022) "11 Trickster Gods From Around The World"); Obika & Eke (2014) (“Tortoise as a Choice for Trickster Hero: A Study of Igbo Folktales”);

Tsuj (2022) (The mouse deer as a trickster in Philippine folktales); Vajić (2017) ("The Trickster’s Transformation – from Africa to America"); Ricketts (1964). (The Structure and Religious Significance of

the Trickster – Transformer – Culture Hero in the Mythology of the North

American Indians); Roberts (1989) From trickster to badman: the Black folk hero in slavery and freedom); Robinson & Douglas (1976) (Coyote the Trickster: Legends of the North American Indians); Carroll (1984) (“The Trickster as Selfish-Buffoon and Culture Hero”); Hynes & William (1993) (Mythical Trickster Figures: Contours, Contexts, and Criticisms); Bassil-Morozow (2015) (The trickster and the system: Identity and agency in contemporary

society); Allan (2004) (The Trickster Shift: Humour and Irony in

Contemporary Native Art. – Tiina Wikström); works cited here; etc. From some of

the listed works, although the list is not exhaustive, one can find that they

have contributed to exploring the different dimensions of the nature of

trickster as well as trickery. Since trickery is a universal concept and

trickster figure is available in almost all culture, this study employs a

simple descriptive methodology to deal with the following issues: 1. The nature

of tricksters and their functions or performances in achieving goals and

objectives; 2. The tricksters around the world and their projection as

archetypical characters; 3. Tricksters and trickery in other media; 4. The

nature of trickery and tricksters in the tribal folktales of Jharkhand; and 5.

Discussion on the universal concepts and culture specificity. A conclusive

remark (“conclusion”) is carefully drafted to limelight the importance of oral

literature of the tribal communities in handling universal concepts.

2. Tricksters and Trickery

In Morphology of the Folktale (1968),

Vladimir Propp identifies thirty-one functions and the sixth one is defined as

trickery with designation (ŋ) – it refers to the attempts of the villain

to acquire the belongings (or take possession of the victim) of the victim by

any means of deceiving and there are examples cited from the Aarne-Thompson

Uther Index (ATU Index) such as disguised villain (162 – dragon takes the shape

of golden goat or 204 -handsome youth; 265 - a witch as an old lady or 258 – a

priest in goat’s hide or 189 – a thief as a beggar woman) and followed by

functions such as persuasion or proceeding to act or employing other means of

deception or coercion Propp (1968): 29-30. From the reference, it can be understood that the villain

performs the trickery in order to achieve the goal – whatever it may be the

forms/means or goals, world folktales are filled with trickster motifs.

However, the Semiotics and Language: An

Analytical Dictionary of Greimas and Courtés (1982), Bloomington: IUP offers a clear and specific meaning of trickster or

trickery in terms of deceiver and deception. The term trickster used in Native

American mythology is treated as corresponding to a deceiver who has the

potential to assume ‘several actantial roles on the veridiction plane’ by

passing off as somebody else in terms of either being or doing. Thematic roles

are done by the deceiver as per the specific semantic investments. However,

deception or trickery is treated as a discoursive figure having its place on

the axis of contradiction – a conjunction of non-being and non-seeming which is

associated with false or opposed to truth, and the same point that the sender’s

movement from truth to lie is mentioned in the separate entry on trickery Greimas and Courtés (1982): 67, 353.

Folklore,

through its mythology and religion, offers a comprehensive understanding of the

nature of trickster, though unrestricted and unconditioned for who can be or

who cannot be, that presents multidimensional features of it – gathered by the

consolidation of characteristics not only from oral and written literature but

also from other media representations. Interestingly, as a multidimensional

figure, it has emerged as somebody who cannot be either confined to any

conventional behaviour of obeying rules or treated as highly intelligent to

hide secrets or play tricks or elevated as an ultimate form of protester or

disrupter of authority. In fact, the trickster figure is highly flexible and

inclusive in nature, even though its anthropomorphic characteristics as seen in

many examples, in the sense that from God to spirit to man to animal - anyone

or anything can appear as a trickster as per the condition of the narrative

structure.

When trickster appears as a character “in

picaresque tales, carnivals, revels, magic rites of healing, man’s religious

fears and exaltations”, Carl Gustav Jung finds that the spirit “of the

trickster haunts the mythology [and folklore materials] of all ages” Jung (1972):140. As the nature of the trickster character is seen by him as an

archetype, “it is stereotypically associated with his name” Blocian (2020):227, and his conception is popularly known as “archetypal psychology”

or “archetypical” Hillman (2016), cf. Blocian (2020):227. The notion of archetype, like unconscious, is not a simple one,

but rather a complex one and it reflects a complex pattern which requires

understanding at anthropological, psychological and philosophical levels. Jung

might have reasons to draw inputs from disciplines apart from psychology for

the understanding of collective unconscious, archetype and self. Archetype

could be a result of collective imagination and ideas and thus it is a form of

action that has been assigned collectively not by self, but by collective

consciousness. For him, it may be having a close connection with instincts on

the one hand and having tension between themselves on the other hand.

Similarly, collective unconsciousness is understood by him not on a speculative

or philosophical level but as an empirical and “decentralized congeries

psychological process.” Jung (1939) cf. Blocian (2020):228-229. The collective unconsciousness, for him, does not have a

direct relationship with ego, because to exist, it must belong to the totality

of the individual, which assures that it is not the component of conscious ego,

which precisely, being present as a ‘sphere in the human psyche’ that makes ‘no

direct relationship with the ‘ego’’. This collective unconsciousness is

considered to be a “potential character”, and it is transcendental character

because it is a priori as well as functioning as a ready-made structure helping

and building human experience on the one hand and collecting ‘information of

the previous course of human development’ Blocian (2020):228-229. Therefore, from the Jungian perspective, the archetype can be

considered as a ‘form of action’ or activity and it is the result of

‘collective imagination and ideas’, and notably, as Jung considers, the human

mind is responsible for everything – not only for the creation of types of

cultures and different social orders and also certain activities – which help

us to understand that imagination is fundamental for guiding any collective

life. As we consider archetype is closely associated with the collective

unconscious, then it can be seen as having Janus-face that one is pointing at

the preconscious and prehistoric world of instinct and the other is potentially

anticipating the future – the past is drawn towards the instinctive of deciding

the future. The Jungian framework of archetypical interpretation of trickster

figures is insightful because there is some universality of patterns could be

defined with it, and it helps to look for a pattern of higher generality.

Indeed, the presence of archetypal figures and certain patterns of actions

indicate the universal foundation of human experience. And, interestingly, Jung

conceptualizes archetype as transcendental and as an unconscious structure, it

transcends beyond “human” (activities) to accommodate “foreign”, “divine” and

beyond “sensual grasp” that is, the collective unconscious being a “pre-human”

with phylogenetic substratum which is equated with the stereometric structure

for having certain unchanging geometric relations. Here, the universality of the

archetype is well connected with a larger framework which interlinks human

development on the evolutionary plot which is substantiated through the

literary examples found in myths and folktales. When compared to the

unconscious, conversely, for Jung, the history of consciousness, covers about

five thousand years, and thus, the myth may be understood as a narration of

unconscious structure and its archetypes, or ‘one of the ways of manifesting

the unconscious’, or in other words, it is a kind of “textbook of archetypes”

or it bridges “the history of culture with collective unconsciousness and

consciousness” Jung (1939) cf. Blocian (2020):231-232. While this bridge between unconscious, social imagination and

the history of culture seems to be the reflection of anthropological processes

or the development of life of species, at the intellectual level, it constructs

various forms of contradiction that exist in human society as a fundamental to

human relationship with the world. Further, in other words, both archetypes and

archetypal images are expressed through myth which makes a relation between

meanings and their relationship with the life of people in a particular

environment or environment of a particular community. Though Jung has treated

them as an archetype, ‘there is an interdependence between them’ and in this

context, Ilona Blocian writes that “myth is, therefore, a plot; the development

of meanings arises from intrapsychic structures, their transgression, mutual

coupling between them and the environment of a given community.” Blocian (2020):232 He quotes Jung that “In myths and fairy tales, as in dreams, the

psyche tells its own story, and an interplay of the archetypes is revealed in

its natural setting” (Carl Jung, CW: 217 cf. Blocian (2020):232).

Jung’s archetypal interpretation having both

philosophical and anthropological features helps us to visualize the essential

aspects of the trickster figure that indicates ‘the characteristics of a

specific experience’ having ‘importance for human life and survival’ Blocian (2020):233. Trickster figure, for Jung, compensates human requirements in

connection ‘with man’s relation to the sacrum’, and that requires that a person or

trickster figure must undergo a kind of change and ‘internal transformation’ as

well as ‘spiritual and moral development.’ However, the interesting aspect of

folkloristic materials is that the ‘motifs and their variants and sets of

meanings’ can be observed, and thus ‘individual dynamics of unconscious

processes and their symbolism’ can be studied using these materials which

provide a certain neutrality to view human life which is the combination of

good and evil Blocian (2020):232. In a similar line, the folklore materials in which the trickster

figure has a prominent place and has different combinations such as

‘spirituality and mental automatism, antithetic elements and harmony of good

and evil’ are useful for interpretation. Blocian (2020):232. As directed by Jung, ‘other forms of culture such as games,

carnivals, and religious rituals’ may also be paid attention to capture the

reflection of mental reality. (Carl Jung, CW: 260, cf. Blocian (2020):233). There are various archetypes that are outside, above, and below

the human level, for example, the archetype of spirit has occupied folklore

materials including fairy tales, legends and myths. The character of the

trickster figure is associated with the image of tension and it has also been

seen as having an atmosphere of enjoyment (for Winnebago Cycle). Archetypal

figures that appear in folktales can also be seen having their appearance in

mythology can help us to interpret the existence of multiple roles in multiple

contexts and it may understand the construction of reality with reference to

these characters, and also, this interpretation may explore the characteristics

of ‘individuation and process of spiritual, cognitive and moral development in connection

with the figure’. From the universal structure to a culturally specific

characteristic of any trickster can be argued because all the properties of a

trickster are considered culturally ordered – whether the property of ‘hiding

the truth’ or ‘overstepping the boundaries of the body’ (Klaus-Peter Koepping

1985) or ‘use of intelligence and wit or cleverness.’ Here some same (universal

topos) to cultural-specific reflection could be seen on a comparative scale.

The trickster figure is an example that

reflects the paradoxes of social life and it is manifested through masking

certain qualities of, for instance, violent urges and simultaneously projecting

other qualities for fulfilling the tasks, this ambivalence is not a new

phenomenon as it is the inherent property of rule of language. That is, even

the game of negativity is rule-governed and purposeful as far as the role of

tricksters is concerned in mythology, folkloric materials, written literature,

and manifestation in the deritualized and secularized forms. If literary satire

is considered ancient, then the trickster figure can also be treated as the

medium to reflect satirical elements with the intention of cleansing society of

its disparities. Further, the trickster figure in some folktales assumes the

role of a rebellious character and it moves to oppose the dominants or protest

against existing structures, limitations, boundaries and order, moreover, this

form or device is socially and ritually acknowledged. However, there are other

forms that fall within performing arts, where one could find trickster

figure-like devices being used, for example, the clown in the

Karagaattam or Kattiyankaran of Terukkootthu of Tamil Nadu, etc. In

addition, the duality of both intelligence and grotesque body images of these

tricksters is an interesting one and it helps them to reach the audience with

their wit and intelligence and helps the performance to move smoothly to the

next level through their timely intervention – which must be seen as an

inversion of order. In both performances, these characters are not called

tricksters, but they are actually performing the tasks of traditional

tricksters through their rhetoric and satirical, and the appearance and

presentation of themselves before the audience are viewed as highly

metaphorical, in the sense of their subversive nature which is sometimes

serious and sometimes laughable. The world they construct during their

performance seems to be a counter universe or in other words, a utopian

counter-world that is too far from the real world. It is apt to quote Enid

Welsford who says that “the fool is an unabashed glutton and coward and knave,

he is – as we say – a natural: we laugh at him and enjoy a pleasant

sense of superiority” Welsford (1935/1961):322, cf. Koepping (1985): 195) and she continues to say that “he winks at us and we are

delighted at the discovery that we also are gluttons and cowards and knaves.” Welsford (1935/1961):322, cf. Koepping (1985): 195). Through the pretension that the trickster is a fool naturally,

the narrative paradigm is accomplished or performance is achieved. This

ambivalent nature of the trickster makes the audience delightful by seeing

the stupidity of others as well as in the fools of themselves – which means

that the joke is the alter ego of the audience. The ambivalence and equivocal

nature of the trickster is already revealed by Levi-Strauss and as a mediator,

it maintains its duality while it mediates Lévi-Strauss (1967/ [1963): 223, cf. Koepping (1985): 198-199). If a trickster is seen as a rebel, because of having the

elements of ambivalence and ambiguity, and also by having antistructure, we

cannot say that all rebels are tricksters. Thus Klaus-Peter Koepping writes

that “Not all substantive traits, such as thieving or rebelliousness, are

carried through all cultural traditions or diverse genres through time, and

therefore not all jesters, fools, or picaros are tricksters, while the

trickster might have properties common to all.” Koepping (1985): 199). Even though the trickster figures across the globe share

similarities and functional commonalities – appear as clever, intelligent,

fools, with wit and satirical elements, as rebellious, cunning, ambiguous,

enlightened subjects to accept or reject any social structure, as

transcendental, as transgressors, as transformers, as breakers of taboos and

social norms – the cultural context in which they appear cannot be ignored,

which ensures its universal and culture-specific outlook. As revealed by Jung,

this universal archetype falls under the unconscious but slips into the

conscious mind with the mediation of myth and symbol. The significant role of

trickster tales, as exposed by Jung, is understood from their move to liberate

mankind from frozen structure, that is, they help us to escape from social

protocol and are seen as having no commitment to any group. Since they are

‘liminal’, ‘pre-social’, ‘pure and unhindered’, therefore, the structures of

the human world are falsified by the tricksters with their powerful primal

energy. In many of the examples found across the globe, one can find that the

tricksters are curing people by extending a healing touch to those who are

wounded by mental trauma. Considering their indispensable occupations in

literature and spiritual life, the trickster figures are much broader than we

assume, and a glance at them will help us in comprehending their global

manifestations.

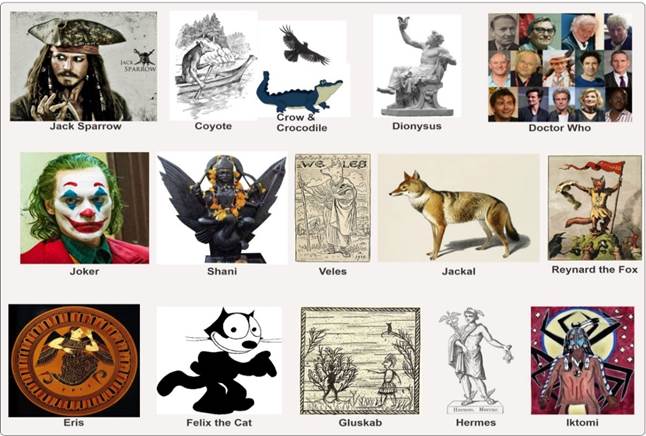

3. Trickster Gods in World Mythology and Folkloric Materials, etc.

There are

archetype figures such as gods (popularly known as “gods of mischief” or “gods

of deception”), mythological figures, and human and animal characters in the

world's literary materials consisting of myths, folklore, and modern

literature. The characters, irrespective of their ontological differences, are

completing their task or purpose with the use of cunning and trickery.

Similarly, it is a regular trope in both mythology and folklore and in some

cases, the figures take different roles of heroic deeds or villainous in

nature, that is, their manifestations are unpredictable, extremely intelligent,

or pretend to be foolish and otherwise potentially dangerous. From the gender

perspective, in most cases, these trickster figures are almost male characters

or genderless animals, and their epistemological nature makes them deviants –

from the conventional framework and normal rules. This brief account will

clarify the ontological and epistemological nature of the tricksters around the

globe: Loki a trickster god is described in Norse mythology for its very

capricious behaviour and also for doing everything with tricks. His parents are

Fárbauti and Laufey (seen as a goddess), and he is the brother of Helblindi and Býleistr. He is married (to Sigyn) and has children. Loki has

varied relationships with other gods – it assists other gods on one occasion

and displays its malicious attitudes towards them on other occasions. Being a

shape shifter Loki appears in the form of a salmon, a fly, a mare, and an

elderly woman. Loki can be found in the folklore of Scandinavia and Denmark

folklore as well as in modern literature. The British actor Tom Hiddleston has

appeared in the Loki character in Marvel movies. People find similarities between

Loki’s “trickery” and Christianity’s Lucifer (the fallen angel). The

thirteenth-century textbook, The Prose

Edda, is considered as a major source for most of the tales of Loki.

(2023). Eris is the Greek goddess of discord and

strife and it is also known as goddess Discordia. And she is known for bringing

about problems wherever she visits. Though she is an ever-present goddess,

sometimes she is sent by others. She seems to cause havoc among gods and men,

she does not play any major roles in stories, that is, she is little known for

her family, her life and adventures. According to the Greek poet Hesiod, the

goddess Eris is the mother of thirteen sons and some of their names reflect the

personification of certain concepts like ‘Forgetfulness’, ‘Starvation’,

‘Manslaughter’, 'Disputes', and ‘Oaths’, and the later, i.e., ‘Oaths’ is

considered as unfortunate son of Eris because, according to the poet, it is

understood that those who are taking oaths without thinking can cause more

problems than anything. The interesting aspect of Eris is that she pits people

against each other, that is, without interfering in their bet or dispute, she

lets the loser carry out atrocities out of their anger. Similarly, according to

another tale, the apple owned by Eris was presented to the woman as a prize for

being chosen as the most beautiful person in Paris, and Eris initiated a Trojan

war due to which many poor people lost their lives – the trouble started with

the clever little prize. There are more tales that present this deceptive

goddess as ‘Strife.’ Monkey King (“Sun Wunkong”) is the Chinese

trickster god who is known for having the magical power to transform into any

animal or object, even a fake version of himself, he is born from a special

stone and with the acquired magical ability, strength and intelligence which

helped him to have immortality to even fight with the god of gods. Wisakedjak

is considered as the crane spirit found in the Central American tales and it is

attributed to Coyote in some tales. This trickster god is known for doing

pranks on jealous or greedy people and it also gives clever punishments to bad

people. There was an old man who had the duty of rising up and bringing down

the fire sun and he had two children – a boy and a girl. One day he was tired

and he felt that it was time to leave. He wanted to know who would take care of

the heavy duty. Both of them had an argument and wanted to take the duty. While

they were arguing, they forgot to raise the sun. The worried people on the

earth looked for the sun, and to end the argument and answer the pleas of the

people, Wisakedjak asked the boy to take over it, and then he created the moon

and asked the girl to look after it. Due to their unwillingness to work

together, they were punished by the Wisakedjak by which both brother and sister

cannot be together and can meet once in a year when both the sun and moon

appear in day time. Anansi, the African spider is considered the

trickster or God of mischief, and originated in African folklore, it could be

found in different forms in American and Caribbean mythology due to the slave

trade. Anansi is known for both – playing tricks and being tricked, and thus,

in most cases, his pranks lead to getting punished by the victims as a matter

of revenge Gregory

(2022). Iktómi (also alternatively known as Ikto/

Ictinike/ Inktomi/ Unktome/ Unktomi) is considered a trickster spirit in Lakota

mythology and it is in spider form and seen as a cultural hero for the people.

Having origin roots in the wisdom god, Ksa, Iktómi is known for having the

quality of shape shifting and he even takes human form. Iktomi

(2023).

Hermes is

another deity known for its ability to move swiftly between divine and mortal

worlds and it belongs to ancient Greek mythology and is considered as the

herald of gods as well as the psychopomp who helps to move the soul to their

respective place (“soul guide”). This “divine trickster” is assigned with the

function and larger responsibilities of protecting human heralds, orators.

travellers, thieves, merchants, etc. Hermes

(2023). Huehuecóyotl (= very old or old coyote) is the

pre-Columbian god found in Aztec mythology and associated with music, song,

dance and mischief, and the patron of uninhibited sexuality. Being a benign

prankster, he plays tricks with both other gods and humans, but most of the

tricks fall on him or put him in trouble. It maintains its duality as good and

bad and thus being considered as balanced, that is, it plays tricks against the

gods and camaraderie with humans Huēhuecoyōtl.

(2023). Susanoo-no-Mikoto who appears as a multifaceted

deity in Japanese mythology is known for having dichotomous characteristics of

good and bad. There are stories that portray him differently, for example, as a

wild and impetuous god with sea and storms; as a heroic figure by killing a

monstrous snake; and as a local deity associated with agricultural activities.

His destructive nature gets him in trouble and he regains it by displaying

heroic deeds (Susanoo-no-Mikoto 2023). Veles (“Volos”) is the major god

in Slavic paganism, and having a spear as a weapon, Perum (thunder god) as its

opponent and also having similarities with Odin, Loki and Hermes, the Veles is

associated with ‘earth, waters, livestock, forests, underworld, music, magic,

trickery, cattle, peasants, and wealth.’ The Veles is known for giving disease

as a way of punishing the oath-breakers Veles.

(2023). Bamapana in Yolngu mythology is considered a

trickster god who is known for causing discord. Interestingly, he often breaks

the taboos by indulging in incest, and thus he is both obscene and profane Bamapana.

(2022). Devil in Christianity is seen as the opponent of

the God and it made an attempt to be equal to God for which it made rebellious

acts against the former. Before God created the material world, he was an angel

expelled from heaven for his constant opposition to God. Considered as the

personification of evil, the devil is seen as an interior realm in opposition

to God. It disseminates its agenda in a tricky way and therefore, it is even

treated as a metaphorical form for reflecting the human inclination for sin Devil

in Christianity. (2023). Dionysus is the Greek God and it is

considered as the God of wine, ritual madness, fertility, and religious

ecstasy. It is seen as the trickster god simply because of shape-shifting as

well as taking other identities. As he is a thorough ambiguous person particularly

in his androgynous form, it is difficult to predict his actions (thus,

associated with theatre and actors). Importantly, he is a liberator (Dionysus

Eleutherios) and he frees people from their self-conscious fear and is

involved in subverting the oppressive restraints of the dominants Dionysus.

(2023). Raven in world folklore and literature is

considered both with positive and negative attributes – loss and ill omen on

the one hand and prophecy and insight on the other hand (- a symbol of “life”

and “death”). It is treated as a mediator or psychopomp that operates between

the material world and the world of spirits. While Greek mythology associates

ravens with the god of prophecy (Apollo), the Roman narrative mentions that

Marcus Valerius Corvus had a raven in his helmet to distract his enemies’

attention during his combat with Gaul. Undoubtedly, there are ancient religious

texts around the world that have references to ravens, for example, the raven

was the very first bird found to be mentioned in the Hebrew Bible that was

released from the arc during the great flood to know whether water was receded,

ravens were used by Jesus, raven is seen as “an example of God’s gracious

provision for all His creatures” Ravens

(2023), the Italian church monk, St. Benedict was saved

by a rave by taking away the bread poisoned by jealous monks, for the German

Emperor Frederick Barbarossa will wake up from sleep to restore Germany to its

ancient greatness if the ravens cease to fly around the mountains, in the story

of Cain and Abel found the Qur’an, Cain learned from a raven the way to bury

his murdered brother, Shani, the Hindu deity is depicted as he is mounted on a

giant raven/crow, the national bird of Bhutan, the hat of the Gonpo guardian

deity Jarodonchen (Mahakala) is adorned with the raven, in the mythology of

indigenous people of North American Pacific Northwest the raven is considered

both the creator of the world as well as trickster god, for example, in Tlingit

culture, the raven in Siberian mythology treats it as a fertile

ancestor-shaman- and trickster Ravens

(2023). As per Hindu mythology, Krishna is a major deity

for preserving and protecting the world. Having a multifaceted personality,

Krishna is also known for being a trickster. To quote Lee W. Bailey who says

that "[a]s a deity of humor, he teased the milkmaids, who adored him, even

stealing their clothes when they were swimming. One moonlit night Krishna

fulfilled the milkmaids’ yearning for union with him, dancing with and

delighting them, which sounds a bit like ancient Greek Dionysian religion"

Bailey

(2014): 1001-1004. Similarly, Narada (Muni) is considered

as a trickster in Hindu mythology, and known for rejecting the life of

sensuality, he often revolts against his father Brahma. His wise and humorous

built-up, being associated with gods, a wandering musician and Vishnu’s devout

follower, Narada is a prominent character who is a sage and the god’s messenger

and has unrestricted access to all the Lokas. There are many stories in Vedic

literature that portray Narada as a trickster Ghosh

(2023), Madhavan

(2019).

4. Tricksters in world Folklore

Apart from

the trickster gods and godly figures, there are stereotypical characters that

are associated with trickery, and there are mere instances in some of the

folklore and in others the characters are meant for that of trickery. Here are

a few examples for the second category, that is, the characters as tricksters.

The Australian Kookaburra is a small bird that comes under the subfamily of

Kingfisher and it is known for human laughing (filled with half cry and

half laugh). There is a popular folktale (“The Kookaburra's Laugh”) that tells

how it got the human laughing or how his laugh finally landed on him: one day

Kenny was hungry and was looking for a juicy giant Australian earthworm.

Meanwhile, another Kookaburra, Kylie was about to devour her own earthworm.

Kenny wanted to grab the earthworm from Kylie by charm and trick and as thinks

himself quite clever, told Kylie about the Billabong where huge juicy

earthworms were available in plenty. She kept the present earthworm secretly in

a hole under the tree. While they were flying to the Billabong, Kenny returned

to eat the earthworm secretly kept by Kylie. However, when he flew to join back

with Kylie at the Billabong, he was shocked to see Kylie having a feast on

juicy earthworms. Missing the feast, Kenny made a strange and distinctive

sound, a hallmark of the Australian bush Taylor

(2018). Pixie (“Pixy”) is the dwarf fairy in

British folklore having a magical power and wearing green dresses. The elf is

known for doing mischievous activities including frightening people, blowing

candles etc. The term pixie-led or pixilated is derived from its pranks but

also refers to someone who lost his familiar road or in an extended form

or the state of bewilderment or confusion. (Anna Eliza Bray, the British

novelist is known for discussing at length in her The Borders of the Tamar

and Tavy (1837)) Britannica (2019). Brownie is an ugly creature in Scottish

folklore known for doing tricks and doing household activities and

mischievously disarranging things at home. Coyote is portrayed

differently as a trickster, creator, magician, glutton, etc., in the folklore

of indigenous people of Western Native America, particularly, in the Great

Basin and California. In many of the folktales, the coyote is involved in

transgressive activities, particularly crossing normative social boundaries

that lead to social and physical chaos to be resolved at the end of the tales,

and its tricks, for example, with porcupine over buffalo meat, with the revenge

of the porcupine, finally resulted in coyote is being tricked Britannica (2019). However, there is also an example that shows the

coyote is a noble trickster when it takes water from the frog people because

all the water cannot be helped by one person Trickster (2023). Found in Abenaki folklore, Azaban (also

Azban or Asban) is a raccoon-type animal character considered as a low-level

trickster spirit, and associated with foolish or mischievous activities, it is

neither dangerous nor malevolent. One tale presents how the Azaban lost its

balance and fell into the waterfall. According to the tale as mentioned by Landau

(1996): 9, Azaban once happened to see a waterfall and

amazed by its noise, thought that it could produce even a louder sound. In

its attempt to shout louder and louder, it lost its balance and fell in to end

its own life (cf. Azeban. (2023). Thai folklore has a

trickster as an anti-monarch and as a subvert known as Sri Thanonchai

which is understood to have an intellectual rivalry with others including King

Ayutthaya who used to harass the peasants with harsh laws and taxes. With his

tricks that are sinister and sadistic in nature, he constantly opposed the

orders of the monarch and escaped from executions on many occasions by proving

innocence through wordplay or interpretation Sri Thanonchai. (2022). Ti Malice as a

trickster character occupies a prominent place in Haitian folklore, and he is

identified as smart and guileful. It is always associated with Uncle Bouki who

is hardworking but greedy. Having origins in African folklore, the two

characters are seen as the split of the Anansi of Ghana folklore Ti Malice & Bouki (2023).

Anansi as a spider character has

its origin in Akan folklore and is associated with the stories of gods, wisdom

and trickery. The Anansi is also known for its ability to outsmart and defeat

even its dominant opponents by using cleverness, and Anansi is often described

as a protagonist due to its inherent ability to transform his weakness into

virtues Anansi. (2023). Gwydion is a multidimensional

character and it appears as a trickster, hero and magician in Welsh folklore Gwydion.

(2023). Being a popular trickster character from

Brazilian folklore, Saci is known for smoking a pipe and wearing a magical cap

so that he can appear and disappear according to his wish. This one-legged

black incorrigible prankster is seen as annoying, dangerous and malicious being

for people albeit he grants wishes to those who can grab his magical cap or

trap him. There are variants of him such as ‘Saci-pererê (black as coal),

Saci-trique (bi-racial and more benign), and Saci-saçurá (with red eyes)’ Saci

(2023). Br’er (Brother) Rabbit is an interesting

trickster character that originated in African-American folklore. Rather than

using brawn, it employs wits to succeed and it provokes authority figures and

bends social mores if necessary. It is seen as the representation of the

enslaved Africans who used their wits to overcome adversities as well as

revenge on their adversaries – thus emerging as a folk hero Br'er

Rabbit. (2023). Curupira, literally meaning “covered in blisters”

in Tupi language, is the mythological creature found in the Tupi-Guarani myths,

and these myths are popular in some of the regions of Paraguay, Brazil and

Argentina. It gets its name due to red or orange hairs that cover the whole

body, and it resembles a man or dwarf with legs turned backwards which creates

confusion for hunters and travellers. It also produces a high-pitched whistling

sound to scare and drive the poachers and hunters to madness. It attacks those

who try to take more than they need from the forest and the people who attempt

to hunt animals that are giving care to their offspring Curupira.

(2023). Kitsune are foxes that can be found in Japanese

folklore and they are known for possessing paranormal abilities that can help

them to be wiser when they grow older. They have the ability of shape-shifting

to human form, and their examples in yōkai folklore, but they are being

seen as having duality in nature – tricksters as well as faithful guardians,

friends and lovers Kitsune.

(2023). Tikoloshe is a dwarf-like water spirit in Zulu

folklore (mythology), and it is portrayed as mischievous and tricksterous by

its ability to become invisible by drinking water and eating stones. Though it

is the least harmful figure, it scares children, and on some occasions causes

illness or even death to others. However, a pastor can banish the Tikoloshe

from that area. To keep the Tikoloshe away at night to escape from its

mischievous behaviour or its curse, as legend reveals that people keep few bricks

under each leg of their bed, that is, they have to sleep in an elevated

position Tikoloshe. (2023). Zomo the Rabbit is a Nigerian

folktale-based trickster figure and it is also known for being mischievous in

nature, full of slapstick, as a triumphant hero with attractive colour

portrayal for enticing children Zomo

the Rabbit. (2023). Jackals and foxes are found to be popular

tricksters in Indian folktales including the Panchatantra, and in some

tales, these characters are replaced with Brahmin characters. Indeed, there are

examples in which one could see that the protagonist characters do the role of

tricksters as per the narrative paradigm, and here tricks are used by the wise

characters in order to escape from the antagonists – in a story of the jackal

and the rooster, the jackal’s attempt to grab the rooster in a tricky way is

thwarted by wisely playing a trick.

5. Tricksters in popular culture

The

trickster characters are popular among people outside the mythology and

folklore, and they can be found in different media like animation, comics,

movies, television serials, and literary writings. Though appears as human, the

Doctor (Who) is an adventurous extraterrestrial character of Time

Lord in the British science fiction television series broadcast by BBC between

1963 and 1989. Interestingly, it was considered as popular culture in Britain

and other parts of the world, because it emerged as a cult for many

generations. The character is mostly seen as a situation-inverter, or as a

trick-player, or as a bricoleur, or as ambiguous – depending on the

incarnations. Since its inception, thirteen actors have done the different

characters. That is, being seldom a straightforward hero, this lead character

is known for relying not on martial prowess but on wiliness and rhetorical

skill, which is a type of anti-heroism attributed to this character. We learnt

that “The transition from one actor to another is written into the plot of the

series with the concept of regeneration into a new incarnation,

a plot device in which a Time Lord "transforms" into a new

body when the current one is too badly harmed to heal normally. Each actor's

portrayal is distinct, but all represent stages in the life of the same

character, and together, they form a single lifetime with a single narrative”

(Doctor Who 1963). Bart Simpson is a fictional character from The Simpsons, an American animated

television series. Configured as an eight-year-old child, Brat is popularly

known for his mischievous, adventurous, rebellious behaviour and always had

disrespect for authority. Due to the protagonist's portrayal with mischievous

traits, Brat is treated as a bad character by his parents during the first two

sessions, and the role is taken over by his father and the family is projected

as a whole, despite Brat is still holding the breakout character Bart

Simpson. (2023). Bill Cipher is another popular trickster

character in the Gravity Falls animated series telecast by Disney

channels, this demon character is projected as having a resemblance to the

one-eyed triangle and it is known for having different supernatural abilities

for troubling humans. In the series, this powerful inter-dimensional dream

character is the main antagonist and though it has a snappy sense of humour, it

is known for impatience that makes it lose its temper Gravity

Falls characters (2023). Bugs Bunny (appeared in 140 animated films

between 1940 and 1964) is a rabbit trickster and it is considered as similar to

the trickster archetype character of Brer Rabbit. Leon Schlesinger Productions

at Warner Bros created the Bugs Bunny cartoon character in the late 1930s, and

it had a role in the short films, Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies.

It is an anthropomorphic character with a flippant and insouciant personality,

and due to its popularity, it became the American cultural icon and official

mascot of Warner Bros Bugs

(2023). Richard Adam’s debut novel Watership Down

(1972 by Rex Collings Ltd, London) has a group of rabbits in their natural

settings, but they are anthropomorphized with their own cultural settings

consisting of language, culture, folklore and mythology. While the manuscript

was originally rejected by many publishers, Collings accepted it and later it

appeared in animated feature films and animated children's series. Escaping

from destruction, a few rabbits make their effort to build their new home and

in the process, they face perils and temptations. Here, El-ahrairah, the Prince

of Rabbits is portrayed as the rabbits’ trickster folk hero Watership Down. (2023). Hokey Wolf is a cartoon character and it

is a canine trickster who is known for doing scams on his victims. It

appears in the animated television series and it was made by Hanna-Barbera as

part of Huckleberry Hound Show. Being adventurous and making tricky

attempts to get into a simple life, the Hokey Wolf is always found accompanied

by his son who is young, a sidekick and diminutive. Hokey

Wolf. (2023). Jack Sparrow is an interesting but notorious

pirate captain character from the film series Pirates of the Caribbean

produced by Walt Disney, and he uses its wit and deceit to achieve goals. As a

fictional character, Captain Jack Sparrow dissolves any dispute not by force

but by verbal means Jack

Sparrow. (2023). James Jesse and Axel Walker are two tricksters

and supervillainous characters in the DC comics and they first appeared in The

Flash (1960). Among them, the former is seen as a practical joker and con

man who always indulges in damaging his enemies like the flash. The latter is

the teenager but he becomes a new trickster by stealing all the gadgets and

shoes (Trickster (DC Comics) 2023). Felix the Cat is the fictional character

that is popularly known as the ‘transgressor of boundaries’ in the literal

sense. The Felix the Cat was created by Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer in 1919

during the silent film era, this anthropomorphic cat having a big grim, black

body and white eyes became a well-known and well-recognized cartoon character

in film history. Further, it is the only animal character fully realized in the

animation sector of American film history. Gerald Jinx "Jerry" Mouse

is a famous fictional character that has an appearance in the series of Tom

and Jerry produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’. The Tom and Jerry duo

combination is the creation of William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, and the Jerry

character is doing always the role of the protagonist against the antagonist or

its rival Tom Cat. These two characters are not always projected as enemies,

but they have to be teamed up for the occasion Jerry

Mouse. (2023). The Joker is conceptualized as a supervillain and

having the trickster characteristics it is seen as a chaotic counterpart to

Batman. It is created by Bill Finger, Bob Kane, and Jerry Robinson in

1940 for DC Comics. This character is loaded with energy and enthusiasm to

perform all gags and pranks, thus making the character inscrutable and

unpredictable. Another fictional character The Pink Panther featured in

animated series was created by Blake Edwards, Hawley Pratt and Friz Freleng and

designed by Hawley Pratt. We could also find its appearance in the opening or

closing credit lines of some featured films. One of its series The Pink

Phink won the Academy Award under the Best Animated Short Film in

1964. Pink Panther is constructed to play the role of opposite to the Little

Man. Pink Panther is also available in comics and other segments of popular

culture. Its multidimensional utility is amazing and for example, it is very

much associated with charity activities such as it is prominent with few

organizations dedicated to cancer awareness and support. Particularly, it is a

mascot of the Child Cancer Foundation of New Zealand. For Jerry Beck, Pink

Panther is “the last great Hollywood cartoon character” with its own clever new

style Pink

Panther (2023). Similarly, Zoe is another fictional (girl)

character who is considered the embodiment of mischievous behaviour and is also

known for having a powerful imagination and change. Further, Yun-Harla is a

trickster goddess and it belongs to the Yuuzhan Vong religion in the New Jedi

Order series. Woody Woodpecker is another trickster character known for having

a simple version of the trickster. This anthropomorphic character first found

its appearance in the theatrical short films of the Walter Lantz Studio between

1940 and 1972 Woody

Woodpecker (2023). T. Ryder Smith, an American actor had frequent

appearance and neat performed the role of a trickster in the horror film Brainscan. (2023). The film is directed by John Flynn

and it was written by Brian Owens and Andrew Kevin Walker Brainscan. (2023). All these three categories of

examples (Trickster gods in world Mythology, Tricksters in world Folklore,

Tricksters in popular culture), though the lists are not exhaustive, present a

clear picture of the nature of the archetypal character, and with this outline,

we proceed to pay attention to the tribal folktales of Jharkhand.

6. Tribal Folktales of Jharkhand known for trickery and tricksters

The examples are drawn from secondary sources, particularly those that

are available in print, as such the courtesy and acknowledgement are given as

references or bibliographical information, and therefore, no claim is made by

the author on the collection, transcription, and documentation and or

reproduction of these tales. The abstracts of these tales are presented without

any order that are presented in abstracts:

1)

The Wise Jackal (Sarahay (2013): 158. Folktales of Munda): Once a tiger with blurred vision fell into a well when

it was on hunting. A bhisti (water

carrier) came to the well with his goat-skin bag for drawing water, and the

tiger convinced him to save it by giving him a false promise of being grateful

to him forever. The persuaded bhisti

dropped the bag into the well and the awaited tiger got into the bag. When the bhisti pulled him up, the tiger came out

of the well. Forgoing its promise, the tiger wanted to eat the bhisti. The scared and frightened bhisti wanted to get a fair decision

from a third person. He consulted a mango tree which justified the act of the

tiger by citing the unthankful act of a man who gets fruits, shades and fuel

wood from mango trees still he cuts the tree in return. By now a jackal was

passing and the disappointed bhisti

wanted its decision. After carefully listening to the story, the jackal

pretended as if it couldn’t understand how the tiger got into the goat-skin

bag. Fooled by the trick of the Jackal, the tiger got into the bag. Wasting no

time, the jackal fastened the bag and the bhisti killed the tiger at once.

2)

Crocodile and the Jackal (Sarahay (2013): 228-229. Folktales of Santal): When a jackal was

drinking water in a river, a crocodile caught its leg tightly and shouted “hum,

hum” in happiness. Realizing what is happening, the trickster jackal asks the

crocodile to say “yes, yes” then only he can be eaten. When the crocodile opened

its mouth to say “yes, yes”, the jackal freed its leg and ran away. The angry

crocodile vowed to teach him, but the Jackal asked the crocodile to come to the

field the next day to meet him. When the crocodile reached the field the next

day and was shivering, he asked the jackal how he kept himself warm. Telling

that he sits on the heap of hay for warmth, the jackal cunningly asks the

crocodile to do the same. When the crocodile was lying on the heap of hay, the

jackal silently set it on fire which killed the crocodile.

3)

The Helpful Wolf (Sarahay (2013): 180-181. Folktales of Munda): In a village, the king

had a loyal and protective dog that used to take care of his poultry from

jackals. One fine day, when the dog became old and weak, a jackal managed to

steal chicken which made the king throw the dog out of his house. The old dog

went to the forest where he met a wolf. He thought that the wolf might kill

him, but seeing his condition the wolf felt pity for him and decided to help

him with a tricky plan. The next day, the wolf took Rani’s child to the forest.

Not finding the child in the cradle, Rani was desperately searching for it. As

per the plan, barking loudly, the dog got the attention of Raja and Rani and

they followed the dog to the forest where the dog made a mock fight with the

wolf and rescued the baby. So, the Raja got the baby and he welcomed the dog

and was taken care of forever.

4)

The Frog and the Fish (Sarahay (2013): 179-180. Folktales of Munda): When a young Munda woodcutter was

sharpening his axe, a fish from a nearby pond stung his feet. The irritated man

uprooted the Bel sapling. The angry mother tree shed all its fruits upon a cock

which became angry and dug an ant hill which was beneath the tree. The ants

that lost their house bit the snake lying there. Now the snake bit the boar who

uprooted a tree where a bat was sleeping. The bat to hide itself entered into

the elephant’s ear. The angry elephant uprooted many trees and one tree fell on

the potteries of a woman. The angry woman enquired about the elephant, but he

narrated how he was disturbed by the bat and that was the reason for the chaos.

Interestingly, one after another blamed the next one and claimed their

innocence. Now the fish felt ashamed of its deed, and all the animals decided

to punish the fish for the chaos and destruction. The elephant drank all

the water in the pond, but the frog caught the fish and put it in a pot of

boiling water. However, with the intention of helping the fish, the frog drank

the water to cook fast. While drinking it took the fish and secretly kept it in

his mouth to be transferred to the pond later. When asked, the frog admitted

that it might have swallowed the fish while drinking. Understanding its

negligence, all the animals beat him for his mistake, and the wound became the

marks on his body.

5)

The Boy named Son-in-Law (Sarahay (2013): 196. Folktales of Oraon): In a village, there lived an old blind woman with her

grandson who used to wear two silver bangles, a necklace and earrings. Two

passer-by cheats saw the boy and decided to grab the ornaments. Pretending that

they were the distant relatives of her husband, the two cheats stayed overnight

and made the boy accompany them the next day. On the way, the cheats misbehaved

with the boy and loaded him with heavy luggage. The cheats had some work

somewhere, so they left the boy with the luggage and they warned him not to

open the bamboo box containing a poisonous snake. The boy opened the box and

found delicious parched rice and sweets which he ate as a meal. When the cheats

returned, the boy told them the snake escaped from the box, and they quickly

understood that the boy was clever. Then, the cheats sent the boy to sell his

two bangles to the village oil man who was extracting oil, and the boy trickily

sold both the cheats and escaped with the money. On his return, he saw an old

woman with her granddaughter who wanted his help to cross the river. Introduced

himself as a son-in-law, he promised to help them cross the river one by one

but wanted to carry the old woman second. After reaching the young girl, he

decided to run away with her leaving the old woman other side of the river.

When she shouted his name, people around there misunderstood what he was doing

right. He married her, brought her grandmother, and lived happily ever after.

6)

The Revenge of a Jackal (Sarahay (2013): 200-201. Folktales of Oraon): One day a jackal killed a

kid and when it was about to eat crows with restless sounds alerted the

villagers who beat the jackal and took away the corpse. The jackal waited for

the occasion to take revenge on the crows. Once there was a cyclonic storm with

torrential rain, and on the pretext of providing safety, the jackal invited all

the crows to its den and killed them and devoured them. But the crow he tied to

his tail for breakfast, escaped by wounding the tail by pricking it. Now he

approached a potter claiming to be the messenger of the king and managed to get

a pot. The jackal met a boy who was grazing goats and citing his father, the

jackal wanted a goat in exchange for a pot of ghee. Later the boy realized that

he was cheated as the pot was filled with sand. Now other jackals saw the

jackal with the fatty goat and they became jealous. While the jackal was away

other jackals ate the goat and left the skin. Disappointed jackals made a drum

out of the goat hide and lured the other jackals to take revenge on them. With

the promise of showing the place to find drums, he trickily made the other

jackals jump into the river and kill themselves.

7)

The Running Dog (Sarahay (2013): 200. Folktales of Oraon): A jackal and a dog were good friends. One day, the dog

invited the jackal for dinner, and as he had cooked fowl, both had a sumptuous

meal. In return, the jackal invited the dog trickily with two conditions: must

come moving not running and must reach at sunset. But the dog attempted several

times but his efforts went in vain. By the time, the jackal finished the meal

and offered the leftover bones to the dog.

8)

Budhna Oraon (Sarahay (2013): 203-205. Folktales of Oraon): Budhna Oraon was a potter who had a beautiful wife with

whom the King had an affair. With the intention of eliminating Budhna, the King

ordered him to bring twenty-four heads of jackals, if he failed, he would be

killed. The unfrightened Budhna made a tricky plan and caught twenty-four

jackals, but one escaped; so, he carried only twenty-three heads to the King.

As the King didn’t agree, he made another tricky plan to trap one more jackal.

Earlier, in the name of the storm he brought the jackals to his trap, but this

time he succeeded by applying honey over his body and pretending to be dead and

killed a jackal. Again, the King ordered him to bring him milk of tigress. With

his tricky plan, he managed to get some tigress milk. Again, the King was

disappointed with Budhna. Budhna’s wife had installed an idol and prayed for

turning Budhna blind. Once he realized her plan, trickily he acted as blind and

waited to catch his wife red-handed with the visiting King. When the King appeared,

he managed to kill both of them. While he buried his wife’s body, the King’s

body was thrown in the neighbour’s field. Fearing that he might have mistakenly

killed the King, he consulted Budhna and dumped the body in the buffalo herd.

With the same fear, the milkman consulted Budhna and dumped the body in the

well of a Brahmin. When the Brahmin prepared a pyre for doing the last rites

for the King, Budhna trickily spoke like the spirit of the King. As everyone

believed, they agreed to the demand of Budhna who became wealthy and had a

luxurious life thereafter.

9)

A New Pair of Shoes (Sarahay (2013): 207-208. Folktales of Oraon): In a village, there were two cheats who were friends. As

no one believed them, they left for another kingdom where the King had died the

previous night. The cheats found the opportunity to cheat the king’s sons but

waited for the burial. They dug a pit next to the king’s grave and one cheat

concealed himself in it. The other met the king’s sons and told them that he

had come to ask for the fifty coins borrowed by the king. When the sons wanted

proof, he took them to the grave to get confirmation from the King’s spirit.

When the sons heard the voice of confirmation from pit assuming it was their

father’s, they returned the coins in a bundle. Now this cheat decided to escape

with the coins silently and he left the place leaving his friend in the pit.

After waiting for a while, the other cheat managed to come out of the pit

and decided to teach him a lesson. So, he quickly bought a pair of shoes and

took a shortcut to go ahead of his friend. Now he put one piece of shoes ahead

of his friend who did not pick it up. Now he went further and put on another

piece of shoes and hid himself. On seeing the second piece, he secretly kept

his bundle in the bush and rushed to get the first piece of shoes. Now the

second cheat took the bundle and ran away.

10) The Trick of a Father (Sarahay (2013): 221. Folktales of Santal): There was a farmer whose

sons were lazy, dull and worthless. He became old and severely ill, and he

called his sons to tell them about some gold that he secretly kept in the field

for use after his death. That made sons happy and secure about their future as

they were not interested in hard work. Now the farmer died of his illness and

the sons went to the field and dug some of the parts, but in vain. They didn’t

find any gold even after digging the whole field, and they understood that what

their father told them was a lie (trick). Since now the whole field was dug,

the mother advised them to sow something, and they did. The crop gave good

yielding and their granary was full. They got good money and understood what

their father said.

11) The Younger Brother (Sarahay (2013): 227-228. Folktales of Santal): Once there were seven brothers and the six elder

brothers were jealous of their seventh brother. While sharing the property the

last was given nothing except a goat and still the seventh brother was happy.

One day, when he was away in the field, the elder brothers killed his goat and

left only the skin. Disappointed and shattered by this, he went to the forest

with the skin and as night fell fearing thieves he sat on a tree. After a

while, a group of thieves came and started sharing and distributing their booty

among them. Finding this opportunity, he dropped the skin which made the

thieves run helter-shelter. The boy climbed down and escaped with the money.

Next, the brothers burnt down his hut and gave him a sack of ash. The boy went

to the same tree with the sack of ash and waited quietly. When midnight fell, a

group of thieves gathered and started discussing their share. The boy dropped

the ash and was scared of ghosts, the thieves ran away leaving all their

belongings which were brought home by the boy. Then the boy told his brothers

that he sold his ashes and got huge money. Now, they burnt down their house and

tried to sell the ashes, but they were ridiculed by everyone. The boy trickily

took revenge on them and then married and lived happily.

12) The Cunning Jackal (Sarahay (2013): 243. Folktales of Santal: Once there lived a jackal who played tricks on everyone,

and thus, everyone wanted to take revenge on him. Once he wanted a companion

for a boat ride in the river, and he did a trick to get the attention of a

crane and took it along with him by falsely promising to show a place with

plenty of fish. When they were in the middle of the way, the crane became

restless which made the jackal laugh. The irritated crane pricked a hole and

the water entered the boat. The panicked jackal cried for help and a crocodile

that appeared suddenly wanted to eat the jackal. But the jackal told the

crocodile that there was no enjoyment in eating thin jackal, but he could help

him to reach the shore so that he could show an elephant that was killed by

him. Once the crocodile helped to reach the shore, the jackal asked him to

wait. The crocodile realized it was tricked. By this time, a tiger bounced on

the jackal, but it told the tiger not to eat the thin jackal but fatty

crocodile would be appropriate. The jackal asked the tiger to get some water to

boil the crocodile, and the tiger turned to fetch water, and the

jackal climbed on a tree. The jackal called the crane and tiger fools and

laughed loudly. Irritated crane and tiger pushed the tree and the jackal fell

down. Though the jackal begged for his life, he was beaten up badly.

13) The Bread Tree (Bompas (1909), Tale No. 9):

A boy lived with his mother, and he used to get two breads every day while

going for grazing cattle. One day, he ate one piece of bread and left the

remaining on a rock. The boy saw a bread-tree on the next day, and since then

he used to take bread from it. One day, when he was on the tree, the

Rakshashi (witch) trickily caught him in her bag and escaped. On the way, he

came out of the bag and somehow with the villagers' help, he managed to escape.

The next day, again the old woman managed to bring him home and she asked her

daughter to prepare the meal. The boy asked the girl how she would kill him.

And she told him that she would pound his head in the dhenki. As

trickily pretended that he couldn’t understand, she tried to demonstrate it.

Grabbing the opportunity, he killed her and subsequently, he killed the old

woman too. He took all her property and lived happily ever after.

14) The Protean Old Man (Grignard (2017): 32-34): A childless couple started a poultry farm, and it

became huge in no time. The man wanted to play tricks on his wife. He asked her

to prepare good meat so that they could feed the owl in the mahua tree. He put a condition that she