ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Shivarapatna Stone Craft in Karnataka - Exploring the Transformative Role of Innovation in Traditional Handicraft and Cultural Identity

Tanima Chanda 1![]()

![]() ,

Aneesha Sharma 2

,

Aneesha Sharma 2![]()

![]()

1 PhD

Scholar, Department of Design, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, India

2 Head

of Department, Department of Design, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi,

India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Handicraft sector is one of the

most sustainable product sectors, because of the consumption of untreated raw

materials received unswervingly from the nature. In many developing countries

like India, there are a large number of livelihoods

depending on handicraft business with an anticipated 17.79 million artisans

associated with the sector in the year 2022. The previous

studies indicate the relation between the handicrafts and innovation is both

controversial and imperative. It is suggested that the sector must undergo

incremental innovation for growth and survival in the present times. On contrary there are studies which dispute, considering

cultural traditions as barriers to innovation. Innovation may be introduced

in the technologies aiding to create the craft. While bringing innovation

within the craft techniques and product creation might hinder its cultural

identity. Innovation being one of the prime keyword

of the 9th goal of the SDGs, the goal of this research is to study how

introducing innovation in cultural craft production affects the identity of

the traditional handicraft. For the findings, rapid ethnography was performed

for the exquisite Shivarapatna stone craft. The

craft uses ancient knowledge of Shilpashashtra to hand-craft the intricate Hindu idol statues from granite,

and the associated community and the craftsmen are situated in the Kolar

district of Karnataka, India. An experiment will be conducted to diversify

the stone made craft products to analyse the

outcome. The representational difference of the traditional craft products

and the innovative craft products are then compared and presented with

images. In addition to the comparative analysis,

methodology also focuses on the descriptive approach in the handicraft. |

|||

|

Received 29 June 2023 Accepted 02 May 2024 Published 07 May 2024 Corresponding Author Tanima

Chanda, tanimachanda97@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i2CDSDAD.2023.595 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Sustainable Goals, Cultural Identity, Traditional

Craft Production, Indian Handicraft Sector |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

During the 1900s a lot of artisans, craftsmen and artists lost their employability because of the rising industrialisation, mass manufacturing and globalisation. With the progressing years the internet and introduction to social media became a new sensation to the art and craft business, providing with the platform and reach to millions of people nationwide and worldwide Althizer (2021). In the book Artisan and Handicraft Entrepreneurs, the authors discuss the importance of preserving the knowledge, skill and the asset associated with the local craft production as value to cultural and national heritage. Hence the artisan community is encouraged towards accepting sustainable business practices saving their art form and to keep it flowing in the market Léo-Paul Dana (2022). The local traditional skill knowledge is an asset to the country and study suggests that connecting this skill knowledge with required technology offers to greater goals like sustaining livelihoods and achieving environmental sustainability Pandey et al. (2007), Dana (1999), Dana (2000).

Stone craft is one of the oldest in the world, which is known even to the prehistoric men. The craft is curated with pure hand skills associated to its making, where the learning skills of the craft knowledge is passed on in the family, generation-after-generation as part of the community’s tradition Etienne-Nugue (2009). This pure form of the stone craft knowledge is famously used to make sculpture in various part of the globe and many rich heritage sculptures of the material is mostly found in the south part of the India country in the form of engravings on the Temples Branfoot (2002). It is noted in studies that the teaching methods of these craft practices still follow the traditional method of teaching, which is “Guru-Sishya Parampara”, where the disciple is taught about the tools and techniques of the craft making with ‘hands on technique’, directly from the master craftsman himself Bocchi (2008).

2. Statement of Problem

Numerous illustrious

studies have examined the possibility of reviving a craft by inventing and

modernising its goods while retaining its distinctive characteristics. The goal

of the study is to experiment and analyse the product innovation and diversification

of the Shivarapatna stone craft in order to determine whether the values and

essence of the particular craft are being preserved through the modernization

of its creations, which is in line with SDG number 9—"Industry,

Innovation, and Infrastructure." In

order to achieve the aim of social and economic growth, it will also examine

changes in the employability scale of the skilled tradespeople. This study's

objective is to develop a sustainable economy by innovating traditional

handcraft.

3. Objective

The current study intends

to examine Shivarapatna stone craft and closely examine how traditional crafts

are made. Based on the definition provided by the Harvard business School Catherine Cote. (2022) the study will gather data on the contemporised

innovation to the current craft products to suit the market need, fulfilling

sustainable development goals for product innovation, and analyse the elements

of innovative products to the traditional-ancient form of the same.

4. Research Methods and Methodology

The research methodology

involves the application of rapid ethnography to investigate the Shivarapatna

stone craft. An experimental phase is planned to diversify the products crafted

from stone, aiming to assess the resulting outcomes. The study will involve a

comparative analysis, wherein the representational disparities between

traditional and innovative craft products will be examined. In addition to the

comparative aspect, the methodology incorporates a descriptive approach Hegazy & Elbana (2022), specifically concentrating on the detailed

exploration of the handicraft.

5. Study Of Shivarapatna Stone Craft

5.1. Overview of Art and Craft in Karnataka, India

Karnataka is a region rich

in culture and history. The ancient sculptures and carvings from temples are

evidence of its rich cultural past, which has fascinated both rulers and

regular people for as long as anybody can remember. The wide variety of State

arts and crafts that now adorn former royal residences, opulent bungalows, and

even modest hutments speak to the artist's talent, aesthetic sense, and

decorative qualities. In Karnataka, many craft traditions have been passed down

from father to son, and this continuity has aided in maintaining a wide range

of handicrafts with very high levels of excellence Baral & William (n.d.). In the past, the nobility lavishly patronised the

State's artisans. To encourage craft families to continue producing handicrafts

and to assist them in marketing their products, the government has established

several agencies and design institutes in the modern era. This has assisted in

preserving several craft traditions so that its practitioners may serve both

the native populace and the numerous visitors that travel to Karnataka Ranjan & Ranjan (2014).

5.2. About Shivarapatna

The village of Shivarapatna

is a significant historical location in rural Karnataka, India. Many families in Shivarapatna devote the

majority of their time to carving life into stone; for some of them, it is the

end all and be all. According to local lore and tales, the art of stone carving

has a long history in the village that dates back at least a thousand years to

the Ganga Dynasty Uma (2016). At that time, a travelling stone carver introduced

the craft to the area, and the locals learned the trade from him. Since then,

the craft has been passed down through the generations to the current

Shivarapatna residents. The majority of the deities that artisans carve out of

granite slabs end up in temples all around India. On occasion, they receive

requests from other countries to produce specialised engineering models.

The artisans who built the

Belur, Hampi, and Hoskote temples are said to be the ancestors of

Shivarapatna's Shilpi’s (sculptors). As a result, the designs share a

common artisan aesthetic, making them distinct from one another.

5.3. Preparation of the Traditional Craft

Shivarapatna craftsmen

specialises in making hindu mythological stone idols and sculptures. To make

the labour for the craftspeople easier, the stone blocks are first divided into

tiny pieces. Paint is used to sketch the design that will be carved.

The carving process goes

like this: choosing the stone and making a sketch, rough dressing to remove

material to obtain the basic shape, smooth/flat dressing to define the details,

final polishing with water and emery paper after fitting, finishing with a

variety of carbarundam stones (chane kallu), and fitting the surface.

Black and grey granite,

which is readily accessible locally, is the stone used to create both people

and idols for temples. According to the traits of the deity or goddess, the

artist selects the stones for the idols. Since it is softer than the male stone,

the grey granite is known as "Stree

Shila" (Female Stone). The

black granite is referred to by the local artisans as "Purush Shila" (Male Stone) in their

native tongue.

Following the marking of

the outline, the pattern is carved out using a hammer and chisel to get the

desired form. The fundamental outside arrangement of engraving takes more than

a month to finish. Detailing takes about a month once the fundamental outline

is completed. The sculpture's surface roughness is then improved and smoothed

utilising a grinding machine on the previously carved surface. They even out

the uneven surface of the idol using sandpaper. The finished sculpture is

prepared for marketing once the finishing touches are applied Baral & William (n.d.).

A typical three-foot statue

must go through five steps of painting, polishing, cutting, carving, and

chiselling, taking around three months to finish. There is little room for

development or distraction due to the fierce rivalry. Because of the intense rivalry,

artisans sometimes charge well below market value in order to get an advantage

over their competitors and sell their goods Dokras (2022).

Sandstone with variable

grain density, size, and gripping is used by the artisans to manufacture

polishing tools. The carving requires little effort because the instruments'

ergonomic form fits their hand sizes.

Figure

1

|

Figure 1 Shivarapatna Traditional Stone Craft Tools and Making Process (Image 1-8) |

5.4. Further technical Details of the craft making

When working with Hard

granite, the craftsperson first examines the natural pattern present in the

stone they have chosen. After that, the shaping is done very meticulously with

a chisel and hammers. In order to prevent heat production, water is sprayed frequently.

By rubbing it with sandpaper or a file, the stone is made smoother.

A stone slab has dimensions

for the created figure marked on it. By using a hammer, extra edges are

eliminated from the slab. On large slabs of stone that have been sliced vertically

into smaller slabs, sketchy designs have been done. With the use of a saw, the

object is removed from the slab. Using a hammer and a chisel, this slab is now

shaped into the appropriate shape. A sharp chisel is used for delicate carving.

To further polish, use a hammer and chisel. The stone is chemically prepared

and then left in boiling water for a whole night prior to cutting. The stone's

surface becomes whiter and smoother as a result. With sand or particles of

carborundum, polishing is done for the ultimate finishing. Many of the carved

objects have been painted. Others have fittings made of brass, seeing glasses,

etc.

The stone carver draws a

preliminary outline of the sculpture on the stone block before beginning to

carve the image. The artisans often mist the stone with water while they work

because the friction created by the continual removal of waste material causes

the tools to heat up. Finishing can be done in a variety of methods, such as

using sandpaper, multani-mitti, clay, oil, or cloth.

On a piece of soft or hard

stone that has previously been precisely cut to size, an outline is created.

After the shape's outline has been cut out, the final figure is revealed by

trimming away the extraneous pieces. While this is accomplished with softer

stones by chiselling the superfluous material out of the tougher stones. A

sharp flat-edged iron tool is used to scrape out the same in order to do

this.

5.5. Workspace

The artist separates his

workspace into 2 areas: sculpture area and showcase place in the backyard

On one side, there are raw

materials, artisans at work, tools in use, and views of both finished and

unfinished constructions. One the other, despite the backyard's limited size,

the artist had effectively displayed his sculptures there for guests to view

and buy. Craftsmen combine their modern and traditional work in this way to

show that they are able to meet a variety of changing needs.

Figure

2

|

Figure 2 Artisans Workspace (Image 1-3) |

5.6. Traditional Details of the Craft

The craft making uses the

detailed knowledge of the ancient iconometry Shilpshashtra, Manasara (as mentioned in the vedas), which is ‘navatala’ or ‘dasatala’ (where tala

means palm of hand) for every scale and detailing of the traditional figures of

the handmade sculptures Acharya (1956). The idol figures are made in nine and ten-head scale

and the postures picked specific to the gratitude of the god and the goddess.

In the guidelines of the Shashtras it is mentioned that the sculpture height

(heads) are based on the ranking of importance of the gods and the humans,

where the most important are the tallest G. Siromoney

(1980). Previously the idols used to have a slightly curved

posture and now they all stand upright. They have unique style of sculpting:

male deities with robust busts and slender waists and female deities with broad

shoulders and lots of ornamentation. The natural color of the stones are also

used as the distinguish between the genders of the sculptures. There are a lot

more details that can be visually experienced in the craft, like the different

mudras, facial expressions following a specific grid, symmetry and details of

the postures with the ornamentation, completing the idol and following of the

rituals before finally drawing eyes of the idol (which is said to be adding

life to the figures) Siromoney & Govindaraju (1980). The craftsmen are well versed with the technical

details of the shashtra, and the learning is passed on within generations

through hands-on learning technique by the eldest male member of the family.

Since working with stones is a robust job, only males in the family are

involved in its creations, While the womens may/may not help in drawing the

details on the stones before the precision work. The idols are created

following strict customs and rituals, following with Vishwakarma puja, and the

work place is kept unconditionally sacred.

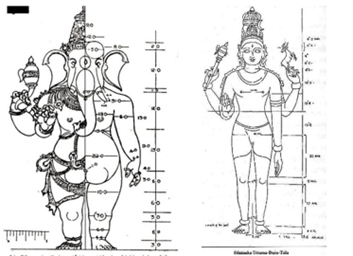

Figure

3

|

Figure 3 Shilpashastra Measurement Guidelines to Head Divisions of Sculptures |

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Uttama Dasatala and Nine Other Talas – by Shilpi Shri Siddalinga Swamy |

Figure

5

|

Figure 5 One Tala Comprises of Twelve Angulas- Shilpashastric Measurements Rao (2012) |

5.7. Significant developments and innovations in the craft over

the years

In the past, hindu

religious sculptures, temple columns and idols were created. These days,

secular sculptures and portraits are carved by sculptors. Additionally, the

themes change in accordance with market need. In addition to creating idols,

artisans also create temple pillars, entrances, and other products based on

consumer demand. For the creation of life-size sculptures of saints and

politicians, craftspeople have adapted to new types of raw materials, such as

reinforced plastic. They produce metal casting procedures at their built-in

foundries in addition to creating stone sculptures to fulfil market demands.

To maintain the intimacy of

touch with the raw material, the artisan builds his own polishing tools to

match various sculpting demands. Sandstone with variable grain density, size,

and gripping is used by the artisans to manufacture polishing tools. With this

they can readily access nooks and deep recesses. In contrast to sandstone,

external materials like sandpaper must be treated carefully and have a short

shelf life. The carving requires little effort because the instruments'

ergonomic form fits their hand sizes. A typical three-foot statue must go

through five steps of painting, polishing, cutting, carving, and chiselling,

taking around three months to finish.

Because of the intense

rivalry, artisans sometimes charge well below market value in order to get an

advantage over their competitors and sell their goods. Today, the freshly

constructed temples or the older ones in need of restoration continue to be the

primary clients, and the stone gods, according to the sculptors, can withstand

the test of time effectively. The metal artisans, known as Sthapati, are

skilled in the Shilpa-shastra, which

is outlined in the Vedas. Traditionally, they were goldsmiths, but they shifted

their field of expertise in response to changing demands of the period.

The idols now all stand

straight instead of their former slightly curled position. They each have

distinctive sculpting styles, with feminine goddesses having broad shoulders

and heavy ornamentation and male deities having strong busts and narrow waists.

According to one of the craftsmen surveyed, good sculptors may earn decent per

month, but this is greatly influenced by seasonal demand and individual orders.

Shilpi Gramme for the village was recently declared by the Karnataka State

Handicrafts Development Corporation Ltd. The Shilpi Gramme will have a training

facility and serve as a venue for sculptors to display their works. It is

intended to inspire the next generation to uphold the family legacy of becoming

sculptors or shilpkars.

6. Product development (experiment)

The Harvard Business school

defines product innovation as the development in the product with improvement

to the present product to serve greater human needs Cote (2022). Also it is the need of the hour for the artisans to

process innovation in the craft production to sustain their livlihood Guha et al. (2022).

It was observed that even

till today, the craftsmen follow the guidelines of shastras, following each

details from drawing till completion of the idol crafting. But with changing

times, the demand of the specific traditional sculptures have seemingly reduced

and the need to produce innovative products of market requirement can be seen

as the need of the hour.

Figure

6

|

Figure 6 Shilpshastra Texts Followed by the Artisans for Idol Crafting (images 1-5) |

For the study, a few

innovative contemporary products were designed to be crafted by the craftsmen

based on the current market requirements (resembling the regular orders they

receive from the current consumers);

1) Simple dhoop stand

2) Plant pot holder

3) Human Sculpture (their personal assigned project)

Key observations:

Object 1 and 2; It was

observed that the considered measurements were according to the universal

standard forms of measurements and not according to the Shilpashastric units.

The tools and materials followed were same as that of the craft, but the significance

of the followed ritualistic procedures for creating the work changed

drastically. The colors of the stones didn’t play role to identify object

gender, there was no rituals before completion of the work, the scale of angulas and talas didn’t play any significant role, neither did the silhoutte

of the output made any resemblence to the traditional Shivarapatna product.

Object 1:

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Preparation of Object 1- Dhoop Stand (Images 1-4) |

Object 2:

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Preparation Of Object 2- Planter Pot Holder (Image 1-7) |

Object 3:

The third object was a

custom order for the craftsmen. On further enquiry it was found that the figure

is of height 5 feets 8 inches approx. and a picture of the same was provided to

the artisan for sculpting the figure on granite rock. For the particular, the

artisan mentioned- because of practising the craft form since so many years and

with his generational learning, it was not necessary for him to follow any

particular unit of measurement as mentioned in Shilpashastra or any

international standard units. He used his muscle memory to craft the

masterpiece with his hands. The tools and techniques in its making were same as

that of idols. There were no followed rituals observed in making of the statue Figure 9.

Figure

9

|

Figure 9 Custom Made Human Figure |

It is observed that the final forms of the developed innovative products are absolute unique and displays no resemblance to the traditional form of the craft. If the below images (Figure 10) are considered, we may observe significant change in the formation of the shoulder blades in both the figures, which clearly implies the changed source of product preparation methods and measurements respectively.

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Product Innovation (left) vs the Traditional Craft Product (right) |

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, while numerous studies emphasize the contribution of past knowledge to future innovations Massis et al. (2016), it is essential to acknowledge the potential drawbacks associated with introducing contemporary innovations into ancient knowledge systems, as it may compromise cultural identity. The analysis of the Shivarapatna stone craft serves as a case in point, revealing a significant deterioration in the cultural significance of products due to introduced innovations. The implementation of a product diversification strategy led to noticeable changes in the approach and aesthetic of the products, despite the continued use of unchanged raw materials, tools, techniques, and craftsmen. In light of the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 9 focused on product innovation, this study raises questions about the suitability of product diversification and innovation as a means to preserve traditional crafts, their associated knowledge, and cultural identity. Further scrutiny is required to assess whether this approach aligns with the overarching goal of sustaining traditional practices and their cultural heritage.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Acharya, P. K. (1956). Indian Architechture According to Manasara-Shilpashastra. New Delhi: Archeological Survey of India, Govt. of India, The Oxford University Press.

Althizer, K. E. (2021). ‘Meet Your Maker: the Women Who Create Etsy’. Department of Anthropology, California State University, Long Beach.

Baral, B., & William, A. (n.d.). D'Source.in. Retrieved From 2023, June 07. Shivarapatna Stone Crafts, The Craft of Stone Carved Sculptures and Idols (last accessed on 31 Jan 2024):

Bocchi, S. (2008). Exploring the Stone-Carving Traditions of India.

Branfoot, C. (2002). 'Expanding Form': The Architectural Sculpture of the South Indian Temple, ca. 1500-1700. Artibus Asiae Publishers 62(2), 189-245. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250266

Catherine Cote. (2022, Mar 24). Harvard Business School. Retrieved From 2023, May 28.

Cote, C. (2022, March 24). Harvard Business School Online. Retrieved From 2023, June 10.

Dana, L. (2000). Creating Entrepreneurs in India. Journal of Small Bus Management, 38(1), 86–91.

Dana, L. P. (1999). Preserving Culture Through Small Business: Government Support for Artisans and Craftsmen in Greece. The Journal of Small Bus Management, 37(1), 90-92.

Dokras, D. U. (2022). How a Temple is Built in Pictures----The Craft of Stone Carved Sculptures and Idols. INAC, 19.

Etienne-Nugue, J. (2009). Tell me About Crafts. France: UNESCO Publishing.

G. Siromoney, M. B. (1980). An Iconometric Study of Pallava Sculptures. Kalakshetra Quarterly, 3(2), 7-15.

Guha, S., Mandal, A., & Dhar, P. (Jan 2022). Stone Carving in India and the Need for Process Innovation. In L.-P. Dana, V. Ramadani, R. Palalic, & A. Salamzadeh, Artisan and Handicraft Entrepreneurs, 149-159. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82303-0_9

Hegazy, S., & Elbana, W. (2022). Innovative Visions to Revive Folk Crafts in Support of Sustainable Development Goals. Information Sciences Letters- An international journal, Lett. 11(5), 1445-1457. http://dx.doi.org/10.18576/isl/1105013

Léo-Paul Dana, V. R. (2022). Artisan and Handicraft Entrepreneurs. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82303-0

Massis, A. D., Frattini, F., Kotler, J., & Wright, A. M. (2016). Innovation Through Tradition: Lessons from Innovative Family Businesses and Directions for Future Research. Academy of Management Perspectives, 30(1), 93-116.

Pandey, N., Garg, A. K., Malhotra, R., & Pandey, D. N. (2007). Linking Local Knowledge to Global Markets: Livelihoods Improvement Through Woodcarving in India. World Dev, 1-9.

Ranjan, A., & Ranjan, M. P. (2014). Handmade in India: Crafts of India. 70 Lebuh Acheh 10200 Penang, Malaysia.

Rao, S. (2012). Sreenivasaraos.Com. Retrieved From 2023, June 10. Temple Architecture – Devalaya Vastu – Part Eight (8 of 9).

Siromoney, & Govindaraju, B. A. (1980). An Application of Component Analysis to the Study of South Indian Sculptures. Computers and the Humanities 14(1), 29-37.

Uma, P. (2016). Hands that Create Gods. Deccan Herald.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2023. All Rights Reserved.