ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Indigenous Knowledge for Sustainable Practices: Reflections on the folkloric forms of Teyyam and Tolu Bommalata

Anjali C 1![]()

![]() ,

Lingala Siva Deepti Reddy 2

,

Lingala Siva Deepti Reddy 2![]()

![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Wadiyar Centre for Architecture, Mysuru

2 Independent

Researcher, Bengaluru

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The inclusion

of culture as the fourth dimension of the sustainable development model

projected by UCLG (2010) affirmed that heritage, knowledge, creativity, and

aesthetics are essential grounds for developing a holistic vision towards

sustainability. Folklore as a significant aspect of human cognition, way of

life and world view not only demonstrates the complex layers of human

existence through generations but also paves the way for a sustainable future

through its cultural dimensions, social functions, and ecological lessons.

The current research examines how two unrelated folkloric forms from distinct

geographic regions emerge as exemplars of sustainable values embedded within

the community. Focusing on the ritualistic performance of Teyyam

from Kolathunadu and the folk-art form called Tolu

Bommalata from Nimmalakunta

region, it argues on the inextricable association of indigenous knowledge

systems with its natural and cultural landscape thereby demonstrating the

case of a sustainable model. A cultic practice prevalent in the cultural

region of Kolathunadu, Teyyam

advocates a strong association with the tribal culture of the land in terms

of its environmental, social, and cultural values. Tolu Bommalata of Nimmalakunta region,

renowned for its distinct cultural expression of storytelling and

entertainment is a living folk tradition of shadow puppetry that combines the

elements of performing as well as visual arts. The research

through a qualitative perspective focuses on ethnographic methods backed by

the documentation and analysis of the tangible aspects of folklore. Apart

from the reflections on the cultural plurality of Indian folklore and crafts,

the study reveals its co-existence with the landscape embodying the

environmental, social, and cultural values thereby demonstrating a

sustainable model in Indian folklore. |

|||

|

Received 29 June 2023 Accepted 16 November 2023 Published 21 November 2023 Corresponding Author Anjali C,

anc@wcfa.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i2CDSDAD.2023.570 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Folklore, Folk-Arts, Sustainability, Indigenous

Knowledge Systems, Cultural Landscape |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

This research entails an examination and interpretation of

the folk forms of Teyyam of Kolathunadu and Tolu Bommalata of

Nimmalakunta as exemplars of sustainable values embedded within the community.

The lens of inquiry adopted for research is the interrelationship between

folklore and its landscape. The concept of cultural landscape defined as a ‘combined

work of man and nature’ forms the theoretical framework of inquiry. Sauer (1941). UNESCO.

(n.d.) Cultural Landscape

defines the dynamic interface between the natural landscape and the evolving

human interventions on it with time. The notion of the Indian Cultural

Landscape (ICL) which is a recent academic discourse discusses the multiple

layers of physical and metaphysical meanings embodied in a landscape. Thakur (2012) Indian settlements

reveal the potential of Indian Cultural landscapes to expand UNESCO's

definition to incorporate its regional connotations encompassing intangible

entities like rituals, memories, folklore etc. Thakur

(2011) Within the conceptual

framework combining the disciplines of folklore studies and cultural landscape,

the paper argues on the inextricable association of indigenous knowledge

systems inherent in folk traditions with its natural and cultural landscape thereby

demonstrating the case of a sustainable model. A

cultic practice prevalent in the cultural region of Kolathunadu, Teyyam

advocate strong association with the tribal culture of the land in terms of its

environmental, social, and cultural values. An in-depth analysis of its

agrarian past, delineation of the interspersed layers of the geographical,

cultural, and political landscape, and the territorial markings manifested in

its sacred realm reveal the environmental associations of this folk ritual. The

magnificent visual pageantry of this folk ritual involves a diversity of skill

sets in its making. The procurement of material resources, intricacies of face painting, making of elaborate headgear,

costumes, attire, and accessories reflect the cultural plurality and indigenous

wisdom embodied in this cultic practice. Tolu Bommalata of Nimmalakunta region, renowned for its distinct

cultural expression of storytelling and entertainment is a living folk

tradition of shadow puppetry that combines the elements of performing as well

as visual arts. It is performed by the

members of the nomadic Charma Chitrakaar community. The diverse skills

and techniques of puppet craft, singing, performing traditional plays,

craft-specific tool making, manipulation of many puppets at a time to create

animation, creative use of light to form silhouettes and the use of traditional

musical instruments reflect the indigenous knowledge of this nomadic community

that constantly evolved in response to the changing environment. The close

links between this folk practice and its landscape are reflected in the

dependency of the craft community on the local resources for raw materials, and

the role of climate in crafting and preserving puppets, which on closer

examination reveals the practice of a sustainable value system among them.

2. Research Methods

An exploratory method was adopted for the inquiry within the qualitative domain and followed a spatial approach supported by the outcomes of the ethnographic survey. The methods and tools of inquiry included literature studies, case study research, semi-structured interviews with the craftsmen, performers, and experts and utilized several documentation and mapping techniques. The studies were delimited within selected parameters based on their significance, association with the landscape and pointers to sustainability. It attempted to examine the folkloric forms in the contemporary scenario and not delve into the historical connotations of it. The influence of historical events was considered for the inquiry even though not the major focus of the research. The field studies and analysis revealed significant similarities between the unrelated folkloric forms under examination. Analysis of the selected aspects like sustainability, traditional knowledge systems and interdependencies with landscape inherent in these folk practices opened up future directions and scope for further research in this multidisciplinary domain.

3. Literature Review

A systematic study and review of available literature generated a comprehensive overview of the existing scholarship on the two folklore forms and the sub-themes of inquiry. An exploratory understanding of folklore and the evolution of folkore studies were provided by the writings of Dundes (1965), p.2, Dorson (1972), Turner (1969) etc. and Indian scholars like Handoo (1989), Vidyarthi (1963) who contributed to the discipline of folkore studies in terms of theoretical propositions and relevant case studies. Kent Ryden’s essay was a significant point which redirected the line of thought towards the reciprocal relationship between folklore and landscape. Kent (1993). The concept of cultural landscape as prescribed by UNESCO. (n.d.) and other significant interpretations of cultural landscape Sauer (1925), Sauer (1941) and the term Indian cultural landscape were analysed to explore the possible association of cultural layers to landscape. Thakur (2012), Singh (2011), Sinha (2011), Sinha (2009) The Indian scholars who contributed considerably to the study of Teyyam as a folk form includes veteran folklore researchers like C M S Chandera, M V Vishnu Namboothiri, K K N Kurup, Raghavan Payyanad (1999), Y V Kannan, etc. The collection of Teyyam songs by Chirakkal T Balakrishnan Nair (1979), Namboothiri (1997), Namboothiri (1990), Namboothiri (1981) marked a momentous contribution to Teyyam studies. The significant attempts by Dr R C Karippath to document and analyse the variants, motifs, and performance spaces of Teyyam, forms imperative contributions to this academic scholarship. Karippathu (2012) A later group of scholars brought in a new line of thought in Teyyam scholarship including Vadakkiniyil (2014), Menon (1993), Komath (2013) etc. Also relevant are the contributions of foreign scholars Freeman (1991), Pereira (2020). The writings of M Nagabhushana Sharma which discuss the making of leather puppets, socio-cultural influence on the style of puppets and its patronage, Sharma (1985), Sharma (1990) that of Palkuruki Somanatha, and KL Kamat which deliberates on the existence of leather shadow puppetry tradition and patronage in history aided an exploratory understanding of this folk tradition. Somanatha (1200), Kamat (1999) B Rama Raju’s book discussed the influence of regional music and instruments, and other local folk art forms on the structure of Tolu Bommalata. Raju (1978) Sarita Sundar discusses the significance of comic relief characters in Tolu Bommalata and the pedagogical role of puppeteers in society. Sundar (2020) The scholarship of Babu Namboodiri K which analysed the stylistic similarities and differences between various shadow puppet traditions of south India also contributed to this study. K (2018) The review of literature analysed and identified the prevailing scholarly discourses, pioneers of the field, governing principles, frictions, and enduring tensions in the respective disciplines addressed by current research. It also revealed the lacunae in existing scholarship and proposed the need for an analytical understanding of folkloric forms in relationship with their landscape.

4. The Ritualistic Performance of Teyyam

Teyyam is a cultic practice of ritualistic possession prevalent in the cultural region of Kolathunadu. A cultural region spread between the Perumba and Valapattanam rivers in the northern part of the Indian state of Kerala, Kolathunadu is tucked between the western ghats in the east and the Arabian Sea in the west. Performed to appease the indigenous folk cults often for a good harvest in agriculture, wealth, prosperity and fertility, Teyyam festivals are organised in the sacred groves and front yards of domestic houses of the region. The close association of Teyyam with the geography, social, cultural, and economic life of the people of Kolathunadu can be deciphered from several aspects of its performance. Namboothiri (1990) The initial part of this research entails an investigation of the folk performance of Teyyam attempting to decode its strong ties with the geography and traditional knowledge systems of the region. The study is delimited to four parameters which can best represent these interdependencies. The first stage examines the role of land as a significant entity in Teyyam folklore. Further, it looks into the evolution of patronage and land rights in the Teyyam tradition which resulted in territorial delineations within the region, and later analyses the physical morphology of Teyyam forms which includes the attire, costumes and face painting in Teyyam.

4.1. Teyyam and its Interdependencies with the Land

Land – as a facilitator of production and as a sacred entity is considered a significant aspect of Teyyam. The spatial and temporal aspects of Teyyam exhibit sound associations with the agricultural practices of the region. The occasion of Teyyam performance can be seen closely corresponding with the agricultural cycle of Kolathunadu. The festivals of Teyyam are conducted between the lunar months of Tulam and Karkidakam which is parallel to the agricultural cycle of wetland paddy and swidden cultivation in the region. Similarly the sacred places of Teyyam performance in Kolathunadu, on close observation reveal their linkages to the agrarian landscape. Many sacred groves locally known as Kaavu were cultivated lands of paddy, garden crops, cash crops or sites of swidden agriculture. A few examples include Vayalile Kottam also known as Chirakutti Puthiya Kaavu at Keecheri, the shrine of Kunnathoorpadi etc. The close equivalence between the agricultural calendar and Teyyam calendar, and that of the territories of Teyyam performance validates the deep-rooted ties of Teyyam with the agrarian culture of Kolathunadu. There are Teyyam cults who indulge in agricultural activities and use agricultural tools in their performance. One such example is that of Arayi Karthika Chamundi considered to be the protector of agricultural lands who crosses the river in a canoe to meet the deity Kalichekon who is the protector deity of the cattle. During this visit, the deities are said to discuss the details of agricultural activities and the prosperity of land and cattle in the region. Valiyavalappil Chamundi is a Teyyam deity who initiates agricultural activity by sowing seeds in the paddy wetlands of Timiri.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Teyyam Deities Participating in Agricultural Activities. Teyyam Deity Valiyavalappil Chamundi Sows Seeds in the Field Celebrating the Onset of an Agricultural Season. Source Photograph

by Mr Prasoon Kiran |

The interrelationship between Teyyam and its geography is also reflected in the interpretation of the region’s undulated terrain associating it with the physiographic zones called Tinai-s as mentioned in the Sangam[1] anthology of ancient Tamil literature. Gurukkal (1989), Ganesh (1997) The heavily undulated topography of the region can be related to the Sangam concept of five unique ecozones known as ‘aintinai’. This includes the long coastal belt called neital tinai, the forested hills and their slopes known as kurinji tinai, marutham tinai which encompass the fertile paddy wetlands, palai tinai which is the parched zone, and the lateritic table lands and pastoral belts called the mullai tinai. The undulated terrain called for the evolution of various cults specific to varying topographies. This can be validated by the strong presence of ancient fertility cults like Kattumedantha, Kurathi, Kankalan, and hunter cults like Muthappan and Wayanattu Kulavan in the eastern highlands, and the sacred centres of canoe cults like Kurumba Bhagavathy, Aryapoonkanni and Ayiti Bhagavathy dispersed along the western coastal belt. Even though there are a group of deities which can be associated with specific geographies of the land, today they can be seen worshipped across the terrain. This phenomenon can be linked to the potential of Teyyam deities to transmigrate territories and traverse across the landscape. There are divine characters in Teyyam mythologies like Ayiti Bhagavathy and Aryapoonkanni who have crossed the 'seven seas’ to reach this land and those divinities who navigated the eastern mountainous region to the plains as a part of cultural and economic exchanges of the region. The movement of deities across the landscape can be linked with the voyages of the social groups who worshipped these deities. Such voyages might have happened as part of military marches and seasonal job seeking which ratifies the close relationship of Teyyam tradition with its geography. Freeman (1991)

4.2. Territorial Delineations of Teyyam Performance

The ritualistic territory of Teyyam performance was delineated within the geography of Kolathunadu and was marked by the assignment of land rights called Cherujanmam. Cherujanmam refers to the sacred territory demarcated by natural boundaries, delineated and assigned to the Teyyam performers and their lineage defining their territory of performance and remuneration. These delineations demanded the performer to be aware of all the events and particulars of his village and kept him rooted in his homeland. The inheritors of cherujanmam rights were expected to render their ritualistic occupational services in the prescribed jurisdiction. Compensations for the service were often received in the form of agricultural products from these lands. Every occupational group including carpenters, oil mongers, blacksmiths, goldsmiths, bell metal workers, toddy tappers, potters, farmers, astrologers, drummers, and other temple servants received such land grants along with their customary titles from the feudal landlords, chieftains or the royalty. Karippathu (2012) Only the entitled social groups were allowed to deliver their services within the jurisdiction and they were not permitted to violate the boundaries of assigned geography. This also meant that they were only allowed to receive their remuneration from the production lands within these boundaries. This practice of land grants mirrored a sustainable traditional land use system in which land was a shared entity commonly held by a community or a group. Each privilege holder operated in a specific part without infringing on another's area.

Many Teyyam performances illustrate the exemplary case of sustainable land management systems which prevailed among the indigenous folk of the region. Teyyam forms known as Nadoditeyyam-s and Veedoditeyyam-s visiting the households of the village during the monsoon months are examples. Such travelling Teyyam deities like Adi, Vedan, and Galinchan visit the households to ward off the evil and epidemics from the villages of north Kerala. These Teyyam deities blessed the villagers and received agricultural products and food grains as honorariums. The rainy monsoon months in Kerala were considered to be a period of famine and poverty and also an off-season for the regular Teyyam performances. The performers managed their day-to-day needs with the remuneration received in the form of food grains and agricultural products from their designated village territories. Thus, Teyyam within the cherujanmam boundaries acted as a balancing entity which took care of the well-being of the communities within its sacred geography.

4.3. Physical Morphology of teyyam: Costumes and Attire

As discussed in the previous section each Teyyam group can be seen fervently associated with its geography. These associations to a great extent shaped and got shaped by the physical morphology of Teyyam forms which includes its attire, costumes, elaborate headgear, and the properties used during the performance. A Teyyam performed in a paddy field or a sacred forest had its own unique morphological identity in terms of the costumes, properties, and form when compared to the one performed in a temple or a domestic house. The landscape became an enduring presence in the Teyyam liturgies, attire, costumes, properties, material offerings and benedictions. For instance, the canoe cults concomitant with the littoral belt of the region exhibited several types of association with marine geography. The headgear of the canoe goddess Ayiti Bhagavathy is designed to represent the hoisted sail of a marine vessel, whereas its lower cloth is representative of the fluttering waves of an ocean. Anilkumar (2021)

The use of agricultural products in Teyyam costumes hints at its association with the landscape. The headgear and adornments of Teyyam use locally sourced wooden planks, bamboo splices, coconut fronds and local plant species like Ixora, Ocimum etc. Ornaments are made in intricate wooden shapes covered with coloured cloth and paper. Beards are woven in jute, breasts carved from wood, coconut shells, or moulded out of bronze, and the masks are made of areca nut leaf sheaths and plantain stem. The sacred weapons, properties and gadgets used for Teyyam are symbolic of the swidden agriculture practices, hunting and gathering traditions and maritime voyages. Several products used in exercising the rituals, material offerings and benedictions were found to be direct derivatives of the idiosyncrasies of associated landscape and varied according to the deities. For instance, Bhagavathy cults offer turmeric while the cults associated with sorcery and exorcism distribute the sacred ash, and the hero gods handed raw rice to the devotees as their blessings. Apart from adornments, the attire and costumes helped establish a superhuman scale for the Teyyam forms which elevated it from the rest of the participants in the performance. Karippathu (2012) The huge headgear designed for its strength, structural stability and resilience to wind movement often highlighted the ‘formal’ presentation of a Teyyam deity. Further to the association between materials and the region, can be observed that each deity can be linked with one or more natural or geographical elements in the region. These geographical associations are often established through the myths, ritualistic offerings, or properties used in the performance. For instance, the fertility goddess Panchuruli is said to have taken its abode in a Banyan tree, the deity of Gulikan is related to Plumeria, hunter cults like Muthappan and Wayanattu Kulavan are associated with the hills, and the hero cult of Kathivanoor Veeran is invocated to the performance space descending from the mountain passes of the western ghats.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Mother

Goddess Deity Performed in a Sacred Grove with its Elaborate Headgear Shaped from

Natural Materials and Local Craft. Source Author |

The association of Teyyam forms with the Tinai-s were not only mirrored in the performance but also appeared as an incessant presence in Teyyam liturgies as material offerings, properties, gadgets, and spaces of performance. The festival markets organised as a part of the Teyyam festivals often acted as local exchange centres for the diverse agricultural and craft products from the contiguous subsistence zones. People from the coastal belt used to bring clay pots and vessels, dry fish etc. and those from the highlands made it with hill products like spices, honey, and various craft products of bamboo. Kalasa Chantha; the famous festival market organized in connection with the Teyyam festival at Mannampurath Kaavu and the festival market at Kannapuram Karankaavu are contemporary models of such erstwhile festival markets. They are celebrated congregations of the local population from surrounding neighbourhoods where rural produce, local agricultural resources, and craft products of the region are exchanged.

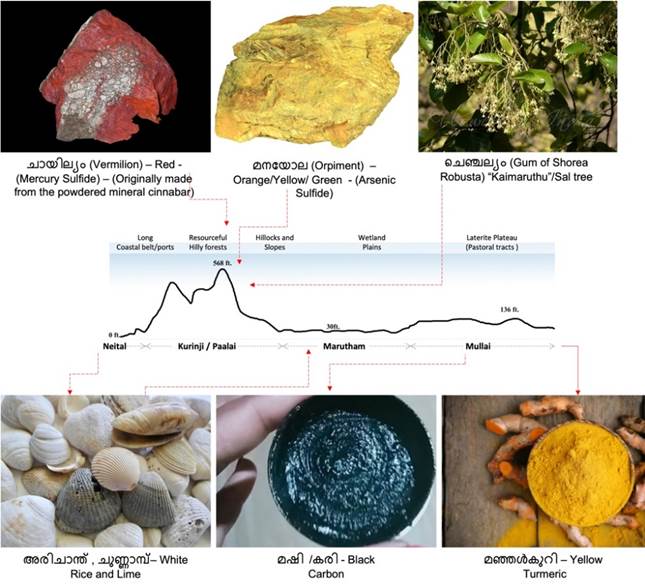

4.4. Art of Intricacies: Face painting

Face painting is one of the most intricate and complex art and crafts in the entire Teyyam attire. It takes hours-long effort to paint the face of a Teyyam performer. The elaborate face-painting styles of teyyam entail a mixture of indigenous herbs and oils sourced from different parts of the landscape, utilizing the indigenous knowledge system of the craftsmen and artists. The major ingredients of face painting in Teyyam include materials like chayilyam (vermillion), manayola, chenjalyam (orpiment), arichandu (rice paste), chunnambu (lime), mashi (black carbon), manjal (turmeric) etc. A closer examination of these materials reveals that their sources are beautifully distributed within the landscape. (Ref Fig 03) Each material can be seen as derived from specific geographical zones in the region. For instance, Chunam or lime from the coastal belts, turmeric from the garden lands and vermillion from the lateritic plains.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Indicative Mapping of the Sourcing of Raw Materials for Face Painting from the Local Landscape Source Author |

Apart from the materials and techniques used, the painting style exercised for each Teyyam form strongly reflected the overtones of its geography. There exist more than forty varieties of face painting styles in Teyyam closely related to the landscape, its flora and fauna. Karippathu (2012) Some of the face painting styles observed in Teyyam deities include Maankannu (eyes of a dear), Narikkurchezhuth (picturizes a tiger), Praakkezuth (dove), Korangirutham (a sitting monkey), Nagamthaannezuth (serpent) etc. Along with face painting other parts of Teyyam attire like Mekkezhuth (body painting), thalachamayam (head adornments), maarchamayam (breast adornments), Kaichamayam, Kaalchamayam (hand and foot adornments), Arachamayam (waist adornments), and thirumudi (headgear) also signifies its association with the landscape. Thus, each teyyam can be seen carrying the essence of landscape in its soul and body. An exploratory study and analysis of face painting styles in Teyyam very strongly suggests that the indigenous knowledge systems stood very close to the biological consciousness of a community.

5. The Shadow Puppetry of Tolu Bommalata

Tolu Bommalata of Nimmalakunta, a living folk art tradition of shadow puppetry is significant for its distinct cultural expression of storytelling and entertainment. The cultural region of Nimmalakunta includes the settlements of Dharmavaram, Chennakesavapuram and Nimmalakunta. It is performed by members of the nomadic community of Charma Chitrakaar-s[2] whose roots can be traced back to the present-day southern part of Maharashtra and Goa. This can be substantiated by the fact that they converse in the Aare dialect[3] within the group and their surnames like Rekhandar, Dalavai, Sindhe, Vanarch, Ataka, and Kanday/ Khande correspond to the surnames of the 96 Kuli Marathas[4]. They travelled in troupes, carrying a portable stage made of bamboo poles and a white cloth screen, and stayed in villages from ten days to a month depending on the length of the performances. Usually performed in the temple precincts, chavadi[5]-s or demarcated open spaces within or in the outskirts of settlements. The animation of puppets is complimented by singing, ventriloquism and the use of the traditional orchestra. The chief puppeteers are known as Kathakudu[6] has a deep knowledge of epics like Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavatam, and narrates these stories in the background of performance. The second part of this research inquiries about the significance of the folkloric form of Tolu Bommalata in terms of its interdependencies with the geography, indigenous knowledge systems and the sustainable practices inherent in it. The folk form was analysed concerning selected parameters like art and techniques of puppet making, sociocultural influences, pedagogical and contemporary significance etc. The diverse skills and techniques inherent to this craft reflect the indigenous knowledge of this nomadic community that constantly evolved in response to the changing environment.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 The Character Representation of Arjuna from Nimmalakunta

Puppetry Depicting the Dynamics of Light Achieved Through the Craft of

Punching. Source Author |

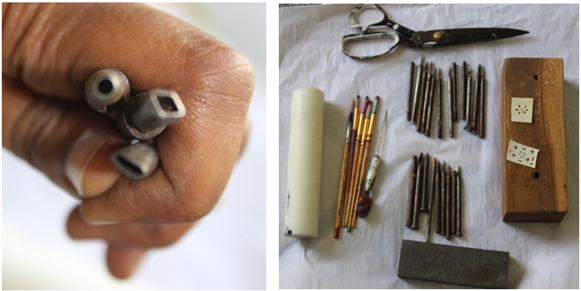

5.1. The Art of Making Puppets: Leather Making, Colours and Tools

Tolu Bommalata is a combination of elements of visual arts and performing arts. It involves two main stages in its making; leather puppet making and storytelling. Traditionally, the hides from deer and goats were used to make puppets of the divine and evil characters respectively, which contrasts with their ancestors who used buffalo skin for all the puppets. Goat and sheep rearing is a predominant occupation in surrounding villages, making it easy to source such local materials. The easy colour absorption properties and stiffness of the male hide made it preferable for the making of leather. There is no tanning involved in this process. The hide is immersed in boiling water, and hair is removed by scraping with sharp knives and dried for two days directly under the sun, by uniformly stretching it in all the corners so that it is thinned to the point of translucence. Being in a semi-arid region has proven advantageous to be able to prepare leather for most of the year as continuous rainfall could have hindered the process.

An outline of the figure is drawn as a free-hand sketch or traced from the previous puppets using Ari (Awl) and the leather is cut along the outline using a chisel. Each characteristic detail is neatly represented which helps in easy identification of characters by the audience. Figures are placed on a Panarayi[7] and perforations of different sizes and shapes are punched with the use of metal punching mould and Gootam[8].These perforations give an illuminated effect to the puppet when placed against light during the performance. The usage of a simple material like leather requires a few unsophisticated tools, but the imaginative skills of the artisans transform it into a complex aesthetic art form.

Figure

5

|

Figure 5 Tools Used for Leather Puppetry Making in Nimmalakunta Source Photograph by Author, Courtesy of Mr Kanday Anjanappa |

Examination of the treasure of antique puppets made by the indigenous groups reveals that traditionally red and black were the only colours used to paint the puppets. As they started migrating, the artisans extracted pigments from natural sources found in the diverse landscapes they traversed. The settlers at Nimmalakunta region painted the puppets with Red (Madhuka flowers) for Hanuman, Pink (fruits of Naga Jemudu, Brahma Jemudu) for the costumes, Green (bacchalaku) for trees, fruits and birds, Blue (neeli leaves) for Krishna and Rama, Yellow (turmeric) for jewellery, karkatashringi (vibrance) and black (from the soot of kerosene lamp mixed with neem gum and water) for demons, outlines, and hair.[9] With these basic colours produced in a long-drawn process by the puppeteers themselves, more shades were created like orange for Sita, violet for costumes and flowers, brown for other characters etc. This contributed to the evolution of the Nimmalakunta style of multi-coloured puppets. The close links of this folk culture with its landscape which is evident by its dependency on local flora and fauna for procurement of leather and dye-making demonstrates the prevalence of a sustainable value system.

Another distinctive feature of Nimmalakunta puppets is that they include multiple intricate and articulated joints with threads on the neck, shoulders, elbows, waist, knees and ankles, which allows the manipulation of puppets with dexterity and sensitivity. During the performance, the puppets are held erect by the grip of a split bamboo stick that extends an extra few inches for the puppeteer to hold and manipulate them. The scale of the puppets which was related to the patronage and the crowd gathered in those times, went up to 10 feet in height having around 13 movable joints thus making them the biggest shadow puppets being crafted in the subcontinent. Interesting rituals are followed to breathe life into a puppet when it is first commissioned to the performance. Thereafter it acquires the status to remain in the Ganiyam[10] where other live puppets are kept. Sharma (1990) Torn puppets are considered unusable and taken to the riverside for final rituals and are respectfully immersed in the river.

5.2. Socio-cultural Influences on the Craft of Puppetry

Late 18th century and early 19th

century inscriptions from Guduru in Warangal and Panugallu

reveal that these puppet troupes might have settled in the areas around Hindupur under the Nayaka rulers crossing the

borders of Karnataka, especially Bellary. Sharma (1990) They travelled on

bullock carts from one village to the other for almost nine months in a year

and returned to their homelands during monsoons. The regional arts and culture

of these new landscapes they traversed, influenced the style of painting,

especially Lepakshi temple murals[11]

and kalamkari textile paintings[12].

This new style with free-flowing lines with a contrasting background brought

three-dimensionality to the figures, decorative borders of the edges, and faces

in profile except for Ravana. Local saree draping styles, rich textile

patterns, hairstyles and exquisite jewellery would have emerged later which

explains the stylistic transformation from Chamdhyacha

Bahulya[13]

which is known for the Mughal-style puppets with beards, and moustaches for

kings and gods wearing baggy pants to a stylized Nimmalakunta

style of Tolu Bommalata. Stylistic

similarities with Thogalu Gombeyata, shadow puppetry of north Karnataka

reinforces the reciprocity between practices. The narration of stories related

to puppetry is entirely contained in the oral traditions of the region. As

Nomads, they were well-versed in Marathi, Kannada and Telugu and

used lyrics from local mythological compositions for storytelling. This

included local texts like Telugu Ranganatha Ramayana, Kavayitri Molla Ramayanam,

Janapada kathalu and Panchatantra

kathalu.[14]

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Stylistic Differences Between the Puppets Made in the Early20th Century and Present-Day Source Author |

A total number of 60 to 80 puppets are required for a performance which also includes figures of trees, birds, chariots, arrows, Vishnu chakra etc. for creating an appropriate setting apart from the mythological characters. The screen where the puppets are projected for the audience to view is slightly tilted forward for the puppets to rest during the play. Lights are placed at a distance from the screen at regular intervals and the puppets are pressed against the screen to appear as a silhouette. Regional instruments like Mridangam, Pavada[15], Gajje, Harmonium and Thalam are used in the performance. According to Sharma, storytelling in Tolu Bommalata has strong connections with local theatre forms like Andhra Yakshagana, Burrakathalu, and street plays where music brings dramatic effect to the play. Sharma (1990) The classical ragas are rendered by the puppeteers in a folk style. Following the saying ‘Adi nata, Antya Surati’[16] The puppet show starts with the breaking of a coconut and an invocation of Ganesha in Nata Raga and Mangalam at the end in Surati. Choric singing between two sets of narrations and climaxing in a tirmanam (‘ta dhai tah’) are inherent like in other regional theatre forms. The comic characters Kethikadu, Bangarakka and Juttu Poligadu are introduced after the preliminaries and in between the narration. They engage with the crowd by narrating crucial plot points in a story, lauding the heroes or kings, and through dance, jokes and quarrels. These puppets were shown to have an explicit sexual nature, short, exaggerated features, and dark figures wearing skimpy clothes. Often the puppeteers were ranked in the society based on the innovations in the puppets of these jesters as it is these characters that make the folk traditions distinct and unique.

5.3. Patronage, Pedagogical Significance and Contemporary Relevance

As storytellers of epics, the community of puppeteers enjoyed significant social status under the patronage of various rulers in history. Due to their itinerant and wandering nature of work, they assumed responsible roles and delivered crucial duties thereby assisting the royalty and chieftains during political instabilities. Through the creative framing of mythological narratives and appropriation of local tales, they served the ruling class to propagate political ideas, communicate crucial messages etc. For instance, the puppeteer community in Maharashtra who were identified as Thakar-s and Gandholi-s, used to march along with the Maratha army during Sivaji's expansion towards the south. They often worked as spies and helped the army in planning and executing their political strategies. Sharma (1990) Further known as Killekyatas during the Vijayanagara they worked for the royalty to help them propagate the good deeds of the rulers among the local population, and as Aare Kapus they worked under the patronage of the local chieftains and landlords in the present-day Andhra and Telangana region.[17] Certain ghatam or episodes are also performed during festivals, death ceremonies and weddings, often to ward off evil spirits and to invoke the rain gods in times of drought in the region.

The occupational groups of puppeteers received land grants from their patrons as remuneration for the delivery of such services. Land grants known as devunimanyalu in the local parlance originally allocated to the temples were re-granted to the puppeteer community. They were allowed to enjoy the produce from these non-transactional agricultural lands if they settled in these villages or else the remunerations took the form of gold, silver, grains and cattle. The performers were also entitled to receive a goat from each herdsman in the village. Thus, the land grants played an inevitable role in keeping the members of these craft troupes rooted in their region. Since three generations when the community of puppeteers started to settle in the Nimmalakunta region, they have always tried to accommodate in their performance the themes of contemporary relevance to help the ruling class propagate their ideologies. Even today they continue to carry forward such practices diligently in terms of social awareness, propagation of government policies and schemes and social consciousness initiatives by NGOs and local bodies. In the contemporary scenario, the physical territory of such traditional performances has undergone a substantial shift wherein the social objectives remain rooted in the context.

6. Results and Findings

The research which explored two distinctive folk genres to comprehend the sustainable value systems encoded in them revealed the significance of studying the folk forms in relation to their landscape. Although the two folk forms are distinctive in terms of their associated geographies the territorial and nomadic dimensions exhibited striking similarities in the way they were entwined with the context and the process through which they evolved into distinctive styles of cultural expression. Both the folk forms exhibit the potential to transmigrate territories and traverse across the landscape. The interdependencies of the community with the varying landforms of the Kolathunadu region resulted in the evolution of diverse cults in teyyam. These territorial markings of Teyyam also correspond to its social, cultural and religious realms. In the case of Tolu Bommalata, the nomadic nature of the community gave it a transboundary dimension wherein the regional traditions were seamlessly exchanged and propagated. It allowed the puppeteer community to explore beyond the delineated region and bring innovations in the craft while staying rooted in context. This resulted in the evolution of the distinctive style of Nimmalakunta Shadow Puppetry. The analysis distilled from these instances ascertains the reciprocal relationship of folkloric forms with the Indian cultural landscape wherein both prove to be evolving with time continuously shaping and getting shaped by each other.

Apart from the geographical significance, these folk forms can also be seen emerging as repositories of knowledge and exemplars of indigenous wisdom in terms of the visual and performing arts, crafts, skillsets, oral traditions, and local mythology inherent in them. They reflected a deep sense of ecological awareness and the manifestation of sustainable practices in every aspect of it right from the procurement of raw materials from the immediate vicinity, indigenous methods of colour extraction from local flora, fauna and minerals, systems of land use, scheduling of performances aligning with the seasons and agricultural cycles etc. Diverse skill sets associated with the making and staging of these folklores and in-depth comprehension and interpretation of local mythologies reflected the indigenous knowledge systems transmitted through generations. Validated by relevant case examples discussed in the paper they emerge as exemplars of sustainable practices inherent in the traditional communities.

All the parameters with respect to which they were studied and analysed proved the inextricable association of Teyyam and Tolu Bommalata with its landscape. The use of local materials, socio-cultural influences, patronage, and the control system established through land grants was found common in the folk practice of Teyyam and Tolu Bommalata which in turn stemmed from its strong interdependence on the landscape. Social inclusion and consistent patronage are factors that played a significant role in keeping the performing communities rooted in the land. Both the folklore forms have designated spaces for performances often related to the agricultural and ritualistic landscape of the region. The system of land grants and traditional systems of land management illustrated through Teyyam, proved ‘land’ to be a significant entity associated with the folk practice. The storytelling and performances in Tolu Bommalata are very much rooted in the context and often played social and pedagogical roles throughout its evolution.

The cultic practice of Teyyam and the storytelling art of Tolu Bommalata though distinct in their historical and cultural evolution, craft, associated social formations, presentation, and performance embodied a significant unifying identity in terms of demonstrating a sustainable value system inherent in the traditional communities. However, it is unfortunate that in the process of conserving and continuing these folk traditions in the contemporary scenario, only the tangible values are recognised whereas the intangible dimensions of the folklore are irreplaceably neglected and lost. Hence the need of the hour is to develop and put in place a holistic approach which looks into the complex, intertwined layers of community, landscape, memory and folklore which ultimately contributes to a sustainable value system. The comprehension of interdependencies between two folkloric forms and its strong association with the landscape emphasise this need which defines the further scope of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Anilkumar, V. (2021). Ekarnna Mala Pole Padarnna Valli Pole. Trivandrum: Chintha Publishers.

Dorson, R. M. (1972). Folklore and Folklife An Introduction. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Dundes, A. (1965). What is Folklore ? In A. Dundes (Ed.), The Study of Folklore, 1-3. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs.

Freeman, J. R. (1991). Purity and Violence: Sacred Power in the Teyyam Worship of Malabar. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

Ganesh, K. (1997). Keralathinte Innalekal. Thiruvananthapuram: Department of Cultural Publications Government of Kerala.

Gurukkal, R. (1989). Forms of Production and Forces of Change in Ancient Tamil Society. Studies in History, 5(2), 159-175. https://doi.org/10.1177/025764308900500201.

Handoo, J. (1989). Folklore: An Introduction. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages.

K, B. N. (2018). Our Traditional Leather Shadow Puppeteers - Leather Shadow Puppeteers in South India. Saradhi.

Kamat, K. (1999). Leather Puppets of India.

Karippathu, D. R. (2012). Theyya Prapancham. Kannur: Kairali Books.

Kent, C. R. (1993). Folklore and the Sense of Place. In Mapping the Invisible Landscape: Folklore, Writing, and the Sense of Place, 53-96. University of Iowa Press: University of Iowa Press.

Komath, R. (2013). Political Economy of the Theyyam - A Study of the Time-Space Homology; Unpublished PhD Thesis. Kottayam: Mahatma Gandhi University.

Menon, D. M. (1993). The Moral Community of Teyyattam: Popular Culture in Late Colonial Malabar. Studies in History, 9(2), 188-217.

Nair, C. T. (1979). Keralabasha Ganangal Part 1 (Malayalam). Thrissur: Kerala Sahitya Akademi.

Namboothiri, M. V. (1981). Thottampattukal. Kottayam: Sahithya Pravarthaka Co-Operative Society Ltd.

Namboothiri, M. V. (1990). Thottam Pattukal Oru Padanam (Malayalam). Kerala Sahitya Akademi.

Namboothiri, M. V. (1997). Kathivanoor Veeran Thottam Oru Veerapuravrutham. Chintha Publications.

Payyanad, R. (1999). Evolution of Folklore Studies. In R. Payyanad (Ed.), Ideology Politics and Folklore, 21-43. Payyanur: Folklore Fellows of Malabar (Trust).

Pereira, F. (2020). A Post-Colonial Instance in Globalized North Malabar: Is Teyyam an "Art Form"? Asian Anthropology, 1-16.

Raju, B. (1978). Folklore of Andhra Pradesh. National Book Trust.

Sauer, C. O. (1925). The Morphology of Landscape (Reprint ed.). University of California Press.

Sauer, C. O. (1941). Foreword to Historical Geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 31(1), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.2307/2560961.

Sharma, M. (1985). Tolu Bommalata - The Shadow Puppet Theatre of Andhra Pradesh. Sangeet Natak Akademi.

Sharma, M. N. (1990). The Shadow Puppet Theatre of Andhra Pradesh. Journal of Sangeet Natak Akademi, 15-28.

Singh, R. P. (2011). Heritagescapes and Cultural Landscapes. Gurgaon: Shubhi Publications.

Sinha, A. (2009). Natural Heritage and Cultural Landscapes Understanding Indic Values. Journal of the Development and Research Organisation for Nature, Arts and Heritage, 4(1), 23-28.

Sinha, A. (2011). Landscapes in India: Forms and Meanings. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.

Somanatha, P. (1200). Panditharadhya Charitamu.

Sundar, S. (2020). Comic Relief, Tholu Bommalata.

Thakur, N. (2011). Indian Cultural Landscapes : Religious Pluralism, Tolerance and Ground Reality. (V. Kawathekar, Ed.), Journal of SPA New Dimensions in Research of Environments for Living "The Sacred" (3), 67-72.

Thakur, N. (2012). The Indian Cultural Landscape : Protecting and Managing the Physical to the Metaphysical Values. In K. Taylor, & J. L. Lennon (Eds.), Managing Cultural Landscapes, 154-172. New York: Routledge.

Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Antistructure.

UNESCO. (n.d.). United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Retrieved From 2018, March 07.

Vadakkiniyil, D. (2014). Anushtanam Kaalam Samoo ham (Malayalam). Kottayam: Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society Ltd.

Vidyarthi, L. (1963). The Maler: A Study in Nature-Man Spirit Complex of a Hill Tribe in Bihar. Calcutta: Bookland Private Ltd.

[1] Sangam

literature includes ancient Tamil literature dating back to the 3rd century BCE

which categorized Tamil poems based on the contextual landscape in which they

are set in. They include two major groups of

texts: Eṭṭuttokai (The Eight Anthologies) and Pattuppāṭṭu

(The Ten Idylls). Refer to Rajan Gurukkal,2010, Social Formations of Early

South India, Oxford University Press for more details.

[2] Charma Chitrakars is a

recently derived term to connote the community of all traditional artists who

work with leather

[3] Aare dialect is a mix of

Marathi and Konkani

[4] Maratha

caste is composed of 96 sub-clans amalgamating different communities called 96

Kuli Marathas.

[5]

Chavadi is the local name for a village meeting place, often a court or a

visitor's lodging place.

[6] Chief

puppeteer

[7] A stone is also used for

sharpening the hand tools and smoothening the leather.

[8] A wooden or metal peg or

a hand hammer

[9] This information was gathered from

unstructured interviews and discussions conducted with the traditional

craftsman of the puppeteer community at Nimmalakunta; Mr. Kanday Anjanappa.

[10]

Bamboo storage box with perforations used to store and transport the puppets.

[11]

Vijayanagara-style mural paintings were executed on the Veerabhadra temple

walls at Lepakshi in the 16th Century.

[12]Kalamkari

textile paintings refer to the Srikalahasthi style ritualistic temple scroll

paintings on textiles depicting narrations of epics.

[13]

Leather shadow puppetry of Pinguli in Maharashtra is practised by the Thakar

community.

[14]They

are the local

folk stories of ancient and medieval kings and local heroes or the local

interpretation of the Puranas and epics.

[15] Pavada: a hollow bone of

a goat, which produces a sound resembling a shankam /conch shell.

[16] This is a popular saying

which can be translated as “The beginning in Nata raga and the ending in Surati

raga”

[17] Kapu is the name of the Telugu agricultural

community who also worked as military chieftains.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2023. All Rights Reserved.