ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF EARLY 20TH CENTURY ARCHITECTURE OF IMPERIAL CITY

Dr. Pankaj Chhabra 1![]() , Silia Grover 2

, Silia Grover 2![]()

![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of Architecture, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar,

Punjab, India

2 Assistant

Professor, Department of Architecture, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar,

India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Calcutta’s established role as India’s premier city from 1774 was increasingly questioned due to its climate and geographic location particularly in the context of British governance and control. By 1857, during the Mutiny, the limitations of Calcutta as the capital became evident, leading Viscount Canning to relocate the British administration to Allahabad. The debate over relocating the capital continued, culminating in 1911 with Hardinge’s proposal to move it to Delhi. This move was seen as a strategic and symbolic shift, with Delhi’s central location and historical significance making it an ideal choice to represent British imperial power. The decision to build a new capital in Delhi, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, was driven by the desire to create a city that embodied both the grandeur of British rule and the historical continuity of India's ancient capitals Jain (1991). Lutyens’ design, characterized by grand processional avenues, monumental plazas, and imposing facades, was intended to project a vision of peaceful dominance and dignified governance. The new city, initially called Imperial Delhi, aimed to reflect the achievements of British rule and serve as a backdrop befitting an empire of Rome’s magnitude. This paper examines the architectural and symbolic values embedded in Lutyens’ design for Imperial Delhi, focusing on its grandiose urban elements and their intended impact. It also explores how contemporary interventions have altered this historic urban landscape, reshaping the legacy of what was envisioned as a majestic symbol of British imperialism. Through this analysis, the paper seeks to understand the evolving significance of Delhi's architectural heritage and its transformation in the modern era. |

|||

|

Corresponding Author Dr. Pankaj Chhabra, ar.pankajchhabra@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.1643 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Neoclassical, Colonial, Modernism, Expressionism,

Imperial |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The choice of Delhi as the British capital was driven not by its commercial or agricultural benefits but by its political and strategic significance. The once-majestic Mughal grandeur had long since faded into decay like "withered leaves on a windless autumn day". The 1857 Mutiny brought this old era to a sudden end. After being neglected for over fifty years Delhi was suddenly made the capital of a vast subcontinent. With this transition, Delhi became the effective seat of a government wielding authority from Kashmir to Colombo and from Calcutta to Karachi. As noted by the Viceroy, Delhi retained a profound resonance in the minds of Hindus, tied to sacred legends older than recorded history and it promised immense satisfaction to Muslims by reinstating the Mughal capital’s former glory as the empire's seat. The British vision for Delhi, as outlined by Hardinge and his contemporaries was intended to usher in a transformative era for India.

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens alongside Herbert Baker was tasked with designing the new capital. Lutyens’ architectural approach characterized by broad, simplified forms inspired by Elizabethan and Jacobean styles or the restrained classicism of figures like Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren, marked a departure from the prevailing Victorian architecture Jain (2010). Baker who had previously criticized Bombay’s Victorian architecture as “a nightmare,” and who also found the High Victorian style in India chaotic and incongruous was aligned with Lutyens disdain for the Mughal buildings which he considered “piffle” and contemporary hybrid designs, which he deemed “half-caste. The British conception of New Delhi was as diverse as the individuals involved in its planning combining elements of urban magnificence with rural tranquility. The design ambitions sought to reflect “the power of western science, art, and civilization”, while simultaneously asserting British dominance over India’s historical monuments. Herbert Baker envisioned the British imprint on Delhi to endure for millennia, aspiring to establish an “Imperial Lutyens tradition” akin to the lasting legacy of Alexander the Great.

2. ISSUES OF AN APPROPRIATE ARCHITECTURAL STYLE

Controversy over the principle of competitive designs for Imperial Delhi was mild compared with the emotion that surrounded the issue of an appropriate architectural style- Indian or European – for the new capital. As early as June 1912, while still simply a member of the Town Planning Committee, Lutyens had observed that already “a fearful battle” was brewing over the question of style. Lutyens’s own outspoken opinions helped fan the flames of debate. His pronouncements about indigenous Indian architecture grew increasingly derogatory with time and exposure. The Mughal buildings scattered throughout north India he thought cumbersome, poorly constructed, and tiresome to the Western mind. Some of the detail he found attractive enough, but then he felt its beauty attributable to outside influences, possibly Italian.

Lutyens felt India had no real architecture: the buildings were just tents in stone and little more. Architecture that seemed to be “all pattern”, “veneered joinery”. The entire debate over architectural style distressed Lutyens as useless “tongue-wagging”. He did not believe there existed any great architectural tradition in India, but simply spurts by various mushroom dynasties, episodes with as little intellect in them, “as any other art nouveau”. As for the hybrid Eurasian style whose multiplicity of Saracenic domes surmounted the public buildings of Madras, he later roundly condemned “that particular form of vulgarity” that British rule had for its monument Irving & Grant (1984). But, as Lutyens recognized, the question was not simply one of taste, but also of high politics. The Viceroy was quite clear on this point: he felt it would be a “grave political blunder” to place a purely Western town on the Delhi Plain. The public in India, he claimed, was very emphatic that the capital’s principal buildings should have an Indian motif. He could not disregard this opinion, lest Indians justly complain he had ignored their tastes while asking them to underwrite the cost. Hardinge reminded his architects that it was not a solely British administration that was raising the new city, as when Calcutta was built, but a joint British-Indian administration. It must be their aim to achieve a style symbolic of twentieth-century India, a composite civilization both Hindu and Muslim, British and Indian. Year by year Indian influence and experience in the administration of government was increasing, making ever more necessary an architecture expressive of the new reciprocity between East and West.

The Viceroy’s projected compromise of Western architecture “imbued with a spirit of the East” was a solution which attracted a wide spectrum of adherents. Herbert Baker, some four months before his appointment to Delhi, in spite of his aversion about Hindu and Muslim architecture had called for a new style of architecture that would reflect the new civilization in India under British rule, “a blend of the best elements of East and West.” Rejecting Gothic and Mughal prototypes for both functional and symbolic reasons, he envisioned a style that would adapt to both a tropical climate and the requirements of the Government. Southern European classicism and the “nobler features” of Indian architecture could provide the necessary elements for such an alchemy: the dome, the colonnade and the arcade, the open court of audience, the deep portal arch or exedra, and formal site planning in the grand manner. Use of the column, Baker later told the Viceroy, was “the crux”. He assured Hardinge he would fully recognize Indian sentiment, but “balconies, oriels, turrets, and dome lets in picturesque confusion” would be unsuitable for a practical Secretariat building, and in Government House they would detract from the intended effect of “awe and Majesty”. Later, the introduction of Indian elements “met the requirements of Eastern sentiment”.

Lutyens urged his British colleagues to create their own patterns according to their needs, rather than hiring them to fit a slogan. This advice applied equally in India, where he discerned two ways to build: either to parade a building “in fancy dress” as at a costume ball, mixing dates and styles, or alternatively to “build as an Englishman dressed for the climate”, conscious only that the tailor was Indian and not English Lang et al (1997). The latter method was clearly his preference: to work within the Western classical tradition, but “unconscious of all but essentials.” He considered simple geometrical shapes the best, and the classical arch, based on the true circle, was fundamental to his conception of architecture in the Indian capital”.

3. EDWIN LANDSEER LUTYEN & HERBERT BAKER

Lutyens’s meticulously designed Viceregal Palace in New Delhi not only symbolized “the ideal and reality of British rule in India” but also achieved a harmonious blend of diverse architectural traditions, dictated by both political and climatic considerations. At Delhi, Mughal architectural elements were seamlessly integrated with the sculptural massing and refined proportions of European design. The Viceroy’s House, grand and imposing, was conceived on a scale reminiscent of Hadrian’s Villa or Shah Jahan’s Taj Mahal, in stark contrast to Lutyens’s more modest cottages and country houses in England.

The Viceroy’s residence presents a cohesive, grand, and harmonious design, reflecting an impersonal and abstract quality akin to the Escorial, which Lutyens admired in 1915. Unlike the vertical emphasis of High Victorian and British Indo-Saracenic architecture, the palace’s design emphasizes horizontal lines. However, it also incorporates the hard, precise edges, broad walls, and sculptural solidity reminiscent of High Victorian style. The building’s colors—buff and rhubarb-red sandstone—echo the hues of the nearby Shahjahanabad and are laid in horizontal bands, enhancing the impression of length Metcalf & Thomas (1989). A prominent red stone plinth, typical of nearby Muslim monuments, further underscores its horizontal orientation. Additionally, the chujja, a characteristic overhanging stone cornice found in Mughal architecture and Indo-Aryan temples from the eleventh century, acts as a crucial unifying feature in Lutyens’s design. (Figure 1) By 1929, as Lutyens’s monumental dome rose above the Viceroy’s House, it became the central visual focus of both the palace and the city. The dome not only dominated the skyline but also symbolized British authority, bridging the legacies of the Roman, Asokan, and Mughal empires with Britain’s own architectural and cultural heritage. (Figure 2)

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Rashtra Pati Bhawan, Delhi- An Edifice of Indo-Sarsenic Architecture |

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Rashtra Pati Bhawan, New Delhi- Fusion of Classical Forms to the

Indian embellishments |

Lutyen’s faithful adherence to these principles in early schemes for Raisina bunglows for Viceregal staff and main staff Bungalows exerted a potent influence over residential design everywhere in the new city. Herbert Baker’s Delhi representative later testified unequivocally to their powerful example. The principal evidence existed of course in scores of houses at Raisina, work by Lutyens’s disciples both in private practice and in the office of Robert Tor Russell, Chief Architect to the Government of India, where most official quarters at Imperial Delhi were designed. Although modest in extent, Lutyens’s contribution to housing at Raisina helped to define a style and set a standard that inspired residential architecture in the Indian Empire for a generation.

Lutyen’s monumental grouping of cruciform structures displayed a pervasive classical vocabulary, skillfully adapted to Indian tradition and weather. On the other hand, Herbert Baker, unlike Lutyens, felt that English classical architecture should be adopted in order fearlessly to “put the stamp of British sovereignty” on the subcontinent of India. Inspite of this, Baker grafted on Chajjas, Chattris and Jalis in much same way as Lutyens did for the Viceroy’s palace. The two vast secretariat buildings at dominating hill top position was meant to impress Indians and indeed to inspire a sense of reverence in all who approached. Such a piazza sacra, Baker felt, reflected the spirit of Indian tradition as found at “all the palaces and big tombs and mosques”, which were raised upon a natural plateau or manmade plinth. As at Viceroy’s House, indigenous architectural forms in the Secretariats were a response to practical climatic needs as well as to the requirements of political symbolism. Baker employed the characteristic Indian features of the open canopied chattri, an ancient royal emblem: the widely overhanging stone chujja, which protected walls and windows from driving rain and midday sun; and the intricately carved stone and marble jaali, which admitted air but not noontime sun. Unlike Lutyens, he also used the nashiman or recessed porch, a re-entrant vaulted portal that distinguishes many Mughal buildings (Figure 3). Baker rejected the “prettinesses” of much Indian ornament, however, preferring “a simplicity which subordinates details of design to a big conception”.

Figure 3

|

Figure

3 North Block, Delhi- An Example

of Political Symbolism |

The Secretariats represented the Grand Manner as Baker defined it: a careful avoidance of pilasters and engaged columns, with wall surfaces kept simple, shadows deep, and lines fluid. Remarkable pavilions crowned every wing, their huge colonnades and dark voids enhancing the impression of sculpted strength. Baker’s Council house at New Delhi likewise reflected the march of constitutional progress.

4. INFLUENCE OF ARCHITECTURE OF LUTYENS AND BAKER

On the parallel lines, R.T. Russel, Chief Architect to the Government of India, and his office prepared the detailed design for Connaught Place along lines which Nicholls had advocated before leaving Delhi in 1917. Airy stuccoed colonnades, punctuated by Palladian archways, afforded protection to shoppers from sun and rain alike, and the elegant, understated classicism. It is one of the major and late classical architectural statements in India (Figure 4). Teen Murti Bhawan design was also in close spirit to Lutyen’s work.Despite all these buildings, Lutyen’s work in Delhi remains the supreme example of twentieth century classical work in India, both in urban design and in architecture.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Connaught Place Delhi- Fusion of Classical Architecture |

5. INFLUENCE OF INTERNATIONAL MODERNISM

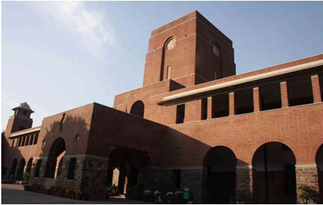

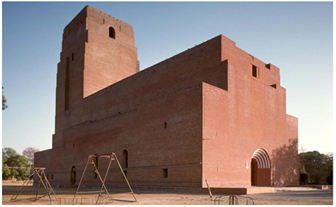

Against this Architectural backdrop, two British architects Walter Sykes George (1881-1962) and Authur Gordon Shoosmith (1888-1974), who had come out to help Lutyens in the design of New Delhi produced buildings radically different from those of major architectural practices. George’s design for St. Stephen’s College, Delhi (1938) is far removed from neo-classical with brick and a stone base. A modified classicism that hinted at the influence of International Modernism can be seen in these works. The simplicity of facades and massing show a dramatic departure from the Contemporaneous work in India (Figure 5). The same observation holds true for Shoosmith’s St. Martin’s Garrison Church (1928-31) in the Delhi cantonment. It was pure European expressionism (Figure 6). It was not, however, until the Indian Architects first came home studying in the United States of America during the 1940’s that such Architecture established more than a toehold in India.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 St. Stephen’s College, Delhi- Simplicity of Facades and Massing Shows

Dramatic Departure from Neo-Classical |

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Shoosmith’s St. Martin’s Garrison

Church-Pure European Expressionism |

International Modernism, born of the rationalist spirit of continental Europe, was the core of avant-garde international architectural practice from 1920 to 1960.It has remained the basis for much subsequent work that has started changing the historic urban fabric of this imperial dream.

Later on, In the first two decades of independence saw

1) The widespread dissemination of those earlier changes

2) The founding of many new Institutions as a result of political Independence

3) Mammoth new Housing programs

It was in this context that Modernist Architecture took off in India. In the short run, it resulted in little change in the nature of architecture because most major Indian architects of the period were either educated by Claude Batley at the Sir J.J. School of Architecture in Mumbai or worked with him in Gregson, Batley and King (GBK), considered as Indian Post-graduate design school from 1920s-1950s and beyond Lang (2000). It was not simply the established private firms, but most of the PWD’s Architectural work of period was an amalgam of the work they had produced during 1930s and the images of modern buildings. The Indian-headed firms were also following similar lines of tentative modernist design in their work. Similar ambiguities pervade the architecture of the Public Works Departments. They faced the problems of how to develop the Mall area of New Delhi that fit in with the architecture of Luytens and Baker without being the same Mitter (1994).

Many of the buildings that align or are adjacent to the Mall today, such as the Supreme Court (1952), Vigyan Bhavan (1962), Krishi Bhavan (1957), Udyog Bhavan (1957), and Rail Bhavan (1962) used Elements of the Indian architectural heritage combined with simplicity of Modernist forms Tillotson (1989). Deolalikar designed the supreme court in an Indo-British style. It is topped by a dome following a precedent set by Lutyens in the design of Viceroy’s palace. It has Chattris that stand in strong contrast to those in the design of Lutyens or Baker and those, for instance, at Fatehpur Sikri (Figure 7).

The Vigyan Bhavan (1955) designed by R.I. Gehlote of the CPWD contain elements of Hindu and Mughal Architecture but its massing and simplicity of form following modernist principles give the building an overall modern air despite its revivalist components (Figure 8).

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Supreme Court, Delhi-An Example of Indo-British Style |

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Vigyan Bhawan, New Delhi-Modern with Revivalist Roots |

So, there is always conflict between Political Ideologies and Rationalist thoughts, that put Indian architects into dilemma about which Architectural path to follow. In the early days of post-independence euphoria, it was Bauhaus rationalism that captured the hearts of many architects. Bauhaus paradigms were soon infiltrated by other ideas, some home - grown, some imported. Another contemporary work, Intercontinental (now Oberoi) Hotel (1958) in New Delhi by Durga Bajpai and Piloo Mody is clearly in the international style promulgated by Gropius. (Figure 9).

The Bauhaus influence also ran through Habib Rahman’s PWD work in New Delhi until the end of 1950s. These buildings include Dak Tar Bhavan (1954) (Figure 10), the Auditor and General Controller’s office (1958) (Figure 11), The Indiraprastha Bhavan (1965), The World Health Organization building (1963), the Curzon Road Hostel (1967), the multistory flats at Ramakrishnapuram (1965) and Patel Bhavan (1972-3). All these works were direct repetition of Bauhaus thinking, which has changed the historic urban landscape of this Imperial dream.

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 Oberoi Hotel, Delhi- Reflection of International Style Propagated

by Gropius |

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Dak Tar Bhavan, Delhi- Inspired from Bauhaus Architectural Style |

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 Auditor and General Controller’s Office-Repetition of Bauhaus

Thinking |

6. CONCLUSION

The city that Lord Hardinge envisioned in 1912 was meant to testify to “the ideal and fact of British rule in India.” The Viceroy had intended the new capital to express peaceful British authority over a composite European and Asian civilization. The undeviating geometry of the city plan had appeared symbolic of Britain’s efforts to impose order and unity on the subcontinent, while the monumental scale of the avenues and principal buildings had implied a permanence that challenged time itself. As the domes and towers fashioned by Lutyens and Baker rose on Raisina Hill, bright against the sky above city and plain, they had seemed to proclaim the success of British discipline and power. But, by the time the architectural work had escaped the demands of its clients ‘for domes’, the work of the first generation of Indian modernists was beginning to make an impact on the Indian scene and the revivalist ideas of the modern Indian architectural movement were already beginning to be forgotten. Despite of variations from the central themes of International Modernism, it was the work of Gropius and the International Style that exerted the strongest influence on Architecture in India and in Delhi from 1930 onwards and until the impact of Le-Corbusier began to be felt on a widespread basis in the 1960s .Reinforced concrete structures and flat concrete roofs, large glass windows in horizontal bands, even when inappropriate climatically, became the hallmark of a modern building everywhere in India, and so in Delhi. It is not surprising that Indian architects have turned to the experiences of others in addressing their own problems. The architecture of the British was politically unacceptable even if it’s slow three centuries-long adaption to regional climates of India was grudgingly admired. In contrast to what Batley offered, the modernists of the first generation sought a complete break from the past and a new vision for the future.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Jain A.K. (2010),

“LUTYENS DELHI”, Bookwell, New Delhi.

Lang, Jon (2000),

“A Concise History of Modern Architecture in India”, Permanent Black, Delhi.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.