ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Preliminary report on the painted Rock Shelters of Rajiv Gandhi Proudyogiki Vishwavidyalaya, Bhopal district

1 PhD

student, Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology, Panjab

University, Chandigarh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This paper

presents the findings from a preliminary exploration and documentation of the

rock shelters located at Rajiv Gandhi Proudyogiki

Vishwavidyalaya in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. The exploration led to the

documentation of three rock shelters painted with Mesolithic-period

paintings. Despite significant neglect and natural degradation, including

fading due to sun exposure, the remaining artworks offer invaluable insights

into the socio-economic and cultural aspects of prehistoric man. Mesolithic

tools discovered on the surface further corroborate the historical

significance of the site and help in the relative dating of the paintings and also help in understanding site utilization. The paper

also brings to light the immediate need for preservation and conservation of

the paintings. |

|||

|

Received 05 June 2024 Accepted 24 July 2024 Published 29 July 2024 Corresponding Author Ritika

Jain, ritikajain2592@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i2.2024.1431 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Rock Painting, Bhopal, Mesolithic, Microliths |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Rock art refers to the “paintings (pictographs) and the engravings (petroglyphs) done on the walls of rock shelters, open boulders and rock formations. The ‘additive process’ makes pictographs wherein wet paint or a dry pigment is added to the rock surface to depict motifs or figures and the ‘reductive process’ creates petroglyphs, where the desired motifs are fashioned out by removing particles from the rock surface by hammering, chiselling, engraving or etching” Chakravarty & Bednarik (1997). Rock art is the “earliest form of human visual expression. It throws light on the culture, society, religious and ritual beliefs, subsistence patterns, tools and implements, technological attainments, flora and fauna of the prehistoric man. Thus, rock art imageries dispense information that corroborates, augments and sometimes, provide new data that cannot be obtained from any other” archaeological source.

This paper is a result of the author’s preliminary

exploration of the rock shelters of the Rajiv Gandhi Proudyogiki

Vishwavidyalaya in district Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. A detailed documentation of

the rock paintings was carried out in the months of October – November 2023. Dr

V S Wakankar previously discovered seven shelters in

the Nayapura region, which, to my knowledge, includes

those within the grounds of the Rajiv Gandhi Proudyogiki

Vishwavidyalaya and the current settlement of Gondipura

Indian

Archaeology (1959-60). However, no data was

published related to his findings.

2. OBJECTIVE

Comprehensive documentation and exploration of the painted rock shelters of Bhopal district have been previously conducted, but the problem that persists is that the previous researchers have failed to publish their findings especially, photographic documentation is lacking. This ultimately leads to the shelters being forgotten, vandalized or eventually falling prone to environmental degradation and the resultant is the loss of a very rich and invaluable source of history that can never be retrieved. Therefore, the primary objective of this paper is to systematically record the data obtained from the comprehensive documentation of the rock shelters of the R.G.P.V campus, thereby bringing to light previously undocumented paintings and rock shelters for further study and analyses. This research aims to apply a multidisciplinary approach by studying the lithic assemblages found in and around the shelters within the gambit of the rock art, thereby, interpreting the paintings to understand the socio-economic and cultural aspects of prehistoric man. Lastly, the research aims to create awareness about the present state of the paintings and the immediate need for preservation and conservation.

3. SIGNIFICANCE

The significance of the research lies in the documentation and therefore preservation of the invaluable cultural heritage of our history that the rock paintings dispense. By creating a visual record of these prehistoric paintings, this paper is adding new data in the field of academia and in the process recording the information, in case the paintings are lost forever. By studying the themes of the paintings, this paper offers a deeper understanding about the symbolism and meanings behind the artwork and therefore understanding the social and cultural aspects of prehistoric man. Shrivastav & Guru (1989)

4. REVIEW OF LITERATURE

With the discovery of Bhimbetka in 1957 by V.S. Wakankar a new chapter in Indian rock art tradition was introduced. Following this, extensive documentation work was carried out in the districts of Raisen and Bhopal, assuming that more clusters of painted rock shelters would be discovered. Wakankar previously discovered seven shelters in the Nayapura region, which, to my knowledge, includes those within the grounds of the Rajiv Gandhi Proudyogiki Vishwavidyalaya and the current settlement of Gondipura Indian Archaeology (1959-60). However, he published no data in the form of the description of the shelters, their exact location and the photographs. Erwin Neumayer in his book ‘Lines on stone’ published one photograph from our study area, but again no information about the shelters and the paintings was provided Neumayer (1993). Recently Meenakshi Dubey Pathak briefly discussed the shelters in R.G.P.V in her book ‘Madhya Pradesh Rock Art and Tribal Art’. However, no detailed description of the shelters and photographs was added. Other than our study area, the rock shelters in Bhopal have been documented by various researchers in the last five decades. V S Wakankar has documented the sites of Dharampuri, Gupha Mandir, Manua Bhan Ki Tekri, Shahad Karad and Shyamla hills in Bhopal district Wakankar & Brooks (1976), Wakankar (2005). S K Tiwari, Rahman Ali and R K Sharma documented the sites of Firangi, Ganesh Ghati, Jamun Khoh, Diga Dig and Lal Ghati Ali & Sharma (1980), Tiwari & Misra (2011).

5. METHODOLOGY

· The rock shelters were located in the forested area of the R.G.P.V campus and a detailed exploration was carried out to locate the painted rock shelters. This exploration led to the discovery of three shelters and detailed documentation was carried out.

·

A Nikon D3200 DSLR

camera was used for photo documentation and digital preservation. These

photographs were later processed using D-Stretch software to enhance the

paintings so that the faint or nearly invisible images are visible again and also to study the superimpositions.

·

An IFRAO

(International Federation of Rock Art Organizations) card was used to ensure a

systematic and uniform method for documentation of rock paintings that will

help in providing a consistent scale reference and ensuring that the colours in

the rock art are accurately represented.

·

A spatial

documentation of the rock shelters has been done using GPS.

·

A number of surface finds of lithic artefacts was collected from in and

around the vicinity of the shelters to understand site utilization and relative

chronology.

6. TOPOGRAPHY

Bhopal District is “situated in the

floodplain of the Betwa river. This floodplain is majorly drained by perennial

rivers such as the Parbati, Kolans, Kerwa, Halali and Kaliasot. The

floodplain is surrounded by a continuous chain of sandstone hills, primarily

composed of pink-red sandstones from the Vindhyan series. These are covered

with a thin layer of the Deccan trap rocks and subsequently covered with Black

cotton soil. The topography is largely made up of these two rock formations and

their accompanying rock types such as flint, quartz, agate, chalcedony,

limestone etc. These hills resemble cuestas and are composed of sedimentary

rocks featuring overhangs and shelters. Rainfall has eroded the softer rocks

under the tough overhanging, resulting in natural rock shelters. Out of the

thirty-one sandstone hills encircling the Betwa source region, Shankar Tiwari’s

explorations identified only eleven hills with rock paintings, while four hills

had no rock shelters. The remaining sixteen hills have been left unexplored and hence termed as terra incognita” Tiwari

(1984). The shelters of Rajiv Gandhi Proudyogiki

Vishwavidyalaya are the northern most part of these sandstone hills.

7. AREA OF STUDY

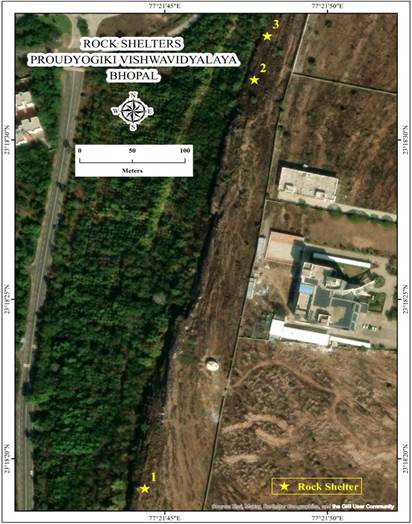

The shelters are currently present inside the campus of the Rajiv Gandhi Proudyogiki Vishwavidyalaya (23° 18' 53.2"N 77° 21' 43.1"E) which is situated in nagar nigam Gandhinagar, tehsil Huzur, district Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. It is 11 km north west of Bhopal and lies on the Ayodhya bypass road.

The rock shelters are in close proximity to the shelters of Gondipura, Manua Bhan ki Tekri and Gufa mandir. The rock shelters form part of a broader and richer concentration of rock art that spreads across the Betwa flood plains in the present day districts of Bhopal and Raisen in Madhya Pradesh.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Map of Research Area |

8. DESCRIPTION OF THE SHELTERS

A total of three shelters were located in the campus. The description of the paintings is given below:

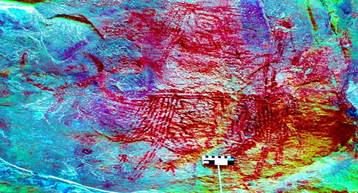

Rock Shelter 1 (23° 18' 19.0692''

N 77° 21' 44.388'' E)

This shelter has a big bison depicted in red, though the front portion

is now very faint (Figure 2). The bison is

painted in outline and decorated with geometric patterns; vertical lines at the

front and back of its body and a square portion in the middle filled with

intricate patterns. The painting was drawn using a thin brush. On the basis of

stylistic variations the bison and other animal can be

dated to the Mesolithic period. Above the bison, another animal painted in red

is depicted in a similar fashion, with an intricate design. However

the animals head has completely chipped off, making it difficult to identify

the animal, but it could be another bovid. To the left the shelter contains a

big intricate pattern, that is difficult to discern and might be part of

another animals body. Additionally, there is a red doe

and a smaller doe depicted under it (Figure 3). The painting is

done in flat wash. The does can also be stylistically dated to the Mesolithic

period.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Painting of a Bison.

Enhanced Using D-Stretch Source Photo by Author |

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Painting of a Doe. Enhanced Using D-Stretch Source Photo by

Author |

Rock shelter 2 (23° 18' 31.8888''

N 77° 21' 47.754'' E)

This shelter contains three very sketchy animals painted in red. The

animal in the middle bears affinity to a bison. It is followed by an animal

that is now worn out and therefore difficult to identify. The bison is facing

an animal that seems to attacking it and looks

ferocious. Again the animal is not easy to identify,

given the chipped off surface of the shelter wall. All three animals are decorated with

geometric designs on the body and can be stylistically placed in the Mesolithic

period. To the right of this composition we have two

dancing figures painted in black (Figure 4). The head of the

both the figures are now defaced. According to

Neumayer, women during the Mesolithic period were drawn full bodied Neumayer (1993) and based on this the figure with the chevron pattern drawn on the body could

be a woman. These figures are also assigned to the Mesolithic period. A portion

of the shelter wall on the right, is heavily superimposed with various layers

painted in red. The upper most layer shows a rhinocerous

adorned with geometric patterns (Figure 5). Below it, an outlined animal, likely a deer,

is depicted in red (Figure 5). A few stick shaped human figures are depicted to the right of the

deer, but it’s difficult to say what activity they are indulging In. The layers

below them cannot be discerned but a few geometric patterns are visible, but no

concrete figure can be identified. This most striking image of the shelter is a

very interesting dancing scene with several figures depicted in red (Figure 6). The figures are

shown schematically with their arms spread and their heads thrown back, as if

in a trance. One figure is wearing an animal mask and the figure next to is

shown wearing a long tunic. The figures are depicted in a circular fashion and

may have been dancing around an object or fire, but its

difficult to tell because the figures in front of them are now completely

faded. One of the human figures is wearing a long cloak and the others are

wearing loincloths. This scene perhaps is a depiction of a ceremonial scene

with shamans. This scene is reminiscent of another painting from Bhimbetka

which V S Wakankar termed as “wizard’s dance” Wakankar & Brooks (1976). This scene can be

stylistically dated to the Mesolithic period. Above this scene is a big boar?

with geometric patterns that is being attacked by a hunter holding a spear (Figure 7). The human figure

is stick shaped in stark contrast to the animal who is naturalistically drawn.

This is superimposed on earlier figures.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Painting of Two Dancing Human Figures. Enhanced using D-Stretch Source Photo by

Author |

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Painting of a Rhinoceros, A Deer and Stick Shaped Humans. Enhanced using D-Stretch Source Photo by

Author |

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Dancing Scene. Enhanced using D-Stretch Source Photo by Author |

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Painting

of a Boar Being Attacked. Enhanced Using D-Stretch Source Photo by

Author |

Rock shelter 3 (23° 18' 33.2604'' N 77° 21' 48.15'' E)

This shelter has a handprint

painted in red. The shelter has a very unique painting

of a stick shaped woman with breasts shown as lines, bending down. It is a rare

picture as stick shaped woman aren’t common depictions. The shelter has a

similar stick shaped woman with breasts and a loin cloth, shown bending but

with a later period bovid depicted under her (Figure 8). The bovid is painted in outline. A later period human is also

superimposed over this picture. This shelter also has a palm print in red (Figure 9).

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 A Stick

Shaped Woman with Breasts. Reconstructed And Original Source Photo by Author |

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 A Palmprint.

Enhanced Using D-Stretch Source Photo by Author |

9. TOOL ASSEMBLAGE

A large

number of finished and unfinished

microliths were found scattered in and around the shelters. The tools were

fashioned out of chalcedony and consisted of blades, borers, scrapers,

triangles and trapeze (Figure 10). Both non-geometric and geometric microliths were found, inferring

that the site was occupied long enough to see technological advancement in the

tool technology and also for the skill of prehistoric

man to develop. The evidence of tools in the various stages of manufacturing

show that the tools were manufactured in the shelters and some shelters may

have been factory sites where the tools were fabricated. The evidence of tools

on the surface is a very important indicator of the rich archaeological

significance of the site and excavations in the future can help us to

understand the importance of this site.

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Mesolithic Tools Source Photo by

Author |

10. CHRONOLOGY OF THE PAINTINGS

The chronology of Indian rock

art has not been established by an absolute method of dating, unlike the rock

paintings of Australia and Europe, which are now securely dated by using AMS

(Accelerator Mass Spectrometer) dating through pigment analysis. Therefore,

rock art researchers in India are still relying on the study of thematic

content, superimpositions, and style of rock paintings in order to establish a

relative chronology Wakankar (2005), Neumayer (1993), Pandey

(1993). The exception to this, are some of the Historic period paintings that

are associated with dated inscriptions to whom some absolute dates can be

assigned.

On the basis

of style, superimposition and theme,

the paintings of this rock shelter have been assigned into the Mesolithic

period.

·

Phase 1- Mesolithic Period

The animals are drawn in outline

in the typical Mesolithic period style of paintings Wakankar (2005), Neumayer (1993) of the Raisen and Bhopal districts, featuring

geometric and intricate patterns decorating their bodies. The human figures are

reduced to stick shaped figures and are in contrast to

the animals who are drawn naturalistically. The overall theme and style of the

paintings show uniformity with the rock paintings of other shelters in the

Bhopal and Raisen district, implying that they belong

to one common artistic tradition.

11. INTERPRETATION OF THE

PAINTINGS

The paintings offer insights into the socio-economic and

cultural beliefs of the cave dwellers. The animals represented include boars,

does, bovids and one rhinoceros. Reflecting the ecological environment of the

Mesolithic period. We get two dancing scenes from this site. The most important

image is the dancing scene of the shamans in shelter number 2. It indicates that the site was used for

magico-ritualistic practices and that the Mesolithic people performed ceremonies. Right next to the dancers, there is a hunting

scene depicting a boar being attacked. The hunting scene is superimposed over

earlier paintings. This means that this particular part

of the shelter was being painted over again and again and therefore has

ritualistic meaning attached to it. The hunting scene and the ceremonial dance

could possibly be part of the same composition and be a representation of the

hunting magic ritual in order to get success in the

hunt. According to Wakankar and Brooks, “In hundreds of paintings men armed with barbed

harpoons, spears, or bows and arrows attack, surround, or dance about an

evidently doomed animal. These paintings may, of course, simply record the

events of a successful hunt. But if an inference can be drawn from reports of

recently primitive societies, the pictures may represent ceremonial magic

before the hunt, invoking a successful outcome” Wakankar & Brooks (1976).

Another important observation

was the lack of Historic period paintings from the site. This could mean that

either we have lost the Historic period paintings or that the site was

abandoned after the Mesolithic period. The evidence of microliths from the surface

corroborates that the site was occupied during the Mesolithic period.

12. PRESENT STATE OF THE SHELTERS

The shelters have been exposed to prolonged mining activities, likely causing the destruction of numerous shelters overtime, thereby, prompting a possibility that this site may have been a very rich repository of rock art. Other than this, the paintings are exposed to direct sunlight, causing them to fade. Additionally, the walls are chipping and facing other natural threats. As a result, the shelters fail to provide a complete picture of the comprehensive view of the rich rock art that must have existed during the Prehistoric period.

13. CONCLUSION

The present research thus, provides a thorough documentation of the rock shelters and the paintings that are assigned to the Mesolithic period. The microliths found from the surface further corroborate the occupation of the shelters during the Mesolithic period and also give information about the tool technology and skills of prehistoric man. Paintings reflecting some sort of ritualistic activities tell us about the beliefs of early man. The animals depicted give us insight into the ecological environment of Mesolithic times. And lastly it raises the need for urgent preservation and conservation of the paintings in order to safeguard a rich source of prehistoric period.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ali, R., & Sharma, R.K. (1980). Archaeology of Bhopal Region. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.

Chakravarty, K.K., & Bednarik, R.G. (1997). Indian Rock Art and its Global Context. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidas Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Indian Archaeology (1959-60). A Review. Archeological Survey of India.

Neumayer, E. (1993). Lines on Stone: The Prehistoric Rock Art of India. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors.

Pandey, S.K. (1993). Indian Rock Art. New Delhi: Aryan Publication.

Shrivastav, P.N., & Guru, S.D. (1989). Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteers: Sehore and Bhopal. Directorate of Gazetteers, Dept. of Culture Madhya Pradesh.

Tiwari, P., & Misra, O. P. (2011). Rock Art of the S-Belt in Central India (Based on the Discoveries of late Prof. Shankar Tiwari). New Delhi: Bookwell Publications.

Tiwari, S. (1984). Twenty-Five Years of Rock Painting Exploration in the Betwa Source Region- A Repraisal. In Chakravarty, K. K. (Ed.), Rock Art Of India: Paintings and Engravings, 228-38. New Delhi: Arnold Heineman.

Wakankar, V.S. (2005). Painted Rock Shelters of India. Bhopal: Directorate of Archaeology, Archives and Museums, Govt. of Madhya Pradesh.

Wakankar, V.S., & Brooks, R.R.R. (1976). Stone Age Painting in India. U.S.A: Yale- Cambridge University.

14. Letter of Authentication

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.