ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Motives of Lajja Gauri in Indian Art: A Study

Ramakant Jee 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Subrata Dey 2

,

Dr. Subrata Dey 2![]()

![]()

1 Research

Scholar, Department of Fine Arts, Tripura University, Suryamaninagar,

Tripura, India

2 Assistant

Professor, Department of Fine Arts, Tripura University, Suryamaninagar,

Tripura, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Art is the

expression of thoughts and feelings, which inspires

by the events around oneself, it takes support of various mediums to express ones feelings and emotions. The matriarchal nature of the

society in ancient times gives stability to our thinking. The reason must

have been that men would have been responsible for collecting the resources

for living in the society and in their absence it

would have been the responsibility of women to run the social system. Almost this tradition is more or less

maintained till today. Such traditions and conditions of contemporary

society are depicted through various mediums of art. In these mediums, it is

necessary to collect some important information regarding the marking of men

and women, some are marked according to the plot described in mythology and

some are independent. The detail study is discussed below with reference. |

|||

|

Received 02 April 2024 Accepted 17 June 2024 Published 30 June 2024 Corresponding Author Dr. Subrata Dey, subbiart@tripurauniv.ac.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.1068 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Assorted, Mother Goddess, Female, Symbols,

Morphological, Culture, Mixed Form, Civilization, Comparative |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The origin and development of art almost all over the

world is not only old, but also with the time of human being to develop.

Symbols found in places Bhimbetka, Raigad, Gadwal, Panchmarhi,

Mirjapur, etc.

in India are living examples of this. It is another matter that they

used to carve this exercise not from the point of view of art but for daily

planning. Most of the figures found seem to be of men figure, possibly hunting

must have been the responsibility of men, and this must have been the main

reason for their marking. But at some places men and women are depicted hunting

together. Over time this trend changed which can be clearly seen in the

artefacts from the Indus Civilization. Whether it is the terracotta idol of the

Mother Goddess or the bronze idol of the dancer, an increase in the depiction

of women can be seen. With the coming of the historical era, a lot of change is

seen in this trend. An abundance of female figures can be seen in Indian temple

architectures Gupta

(2011). But the marking of

assorted female figures is much less than that of men. In Indian art, apart

from Nagdevi

and Kamdhenu, another goddess has

been depicted in a mixed form, she is very important, who is known as Lajja Gauri, as different incarnations

of Lord Vishnu are depicted, similarly Lajja

Gauri is an embodiment of power. Fane

(1975)

Depiction of assorted figures has been an important part of sculpture, painting and architecture not only in India but across the world. In the Indian context, their basis is considered to be mythology and perhaps in other ancient civilizations its main basis would have been cultural belief. According to Indian mythology, there are ten avatars of Lord Vishnu, of which the first four and one other avatar (Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Hayagriva and Narasimha) are depicted as assorted figures. Ganesha is named Gajanan because he has the head of Gaj, that is, an elephant. Vishnu's vehicle Garuda is also depicted as an assorted figure. Lajja Gauri is the most prominent form of the mixed figure of goddesses, as well as Nagadevi and Kamdhenu have also been inscribed. In this article, we will try to know Lajja Gauri. Among the Asuras described in the Puranas, the marking of Mahishasura has also been depicted as an assorted figure. Just as gods and goddesses and demons have been inscribed, similarly some animal figures have also been given an assorted form in Indian art. Gajasimha, an assorted figure with the head of an elephant and the body of a lion, is abundantly depicted in the temples of South India. Pattanaik (2000)

The forms of Lajja Gauri should be seen as symbol of mother goddess. Symbols have been used extensively in Indian art, or rather; an important part of Indian art is dependent on symbols. Symbols are also classified into several categories such as religious, political, social etc. Mishra (2017). The morphological change of symbols adds to the charm of Indian art. Just as a flower has the potential to become a fruit, and a seed within a fruit has the potential to become a new tree. Metaphorical and interpretative properties are likewise referred to within symbols Singh (2014). The maximum expression of the image can be done by the symbol only. The symbol is the true embodiment of the abstract Agrawala (1966). Due to the absence of individual forms in the symbol, it can reveal all the forms of the image. The one who is least affected by the stance himself is the most representative of the image.

2. OBJECTIVES

1) To study, analysis and depictions of Motives of Lajja Gauri in Indian Art

2) To explore the aesthetic and symbolic importance of Lajja Gauri in Indian Art, and analyze their respective positions and the cultural components that connect them.

3. Methodology

This research report is based on visual observation. Additionally, it draws inspiration from Hindu and Buddhist mythology and philosophy. The data required for this research has been gathered from two primary sources: primary and secondary sources. Primary research involves gathering data by conducting interviews, questionnaires, or observations specifically focused on Lajja Gauri, including its symbolism, cultural practices, and creative depictions. The secondary data were acquired through an examination of pertinent published books and journal articles available in the library. The literature review on Lajja Gauri examines important topics, perspectives, and academic discussions. The study's approach mostly relies on descriptive and analytical research methodologies.

4. Explanation

Keeping Lajja Gauri as the focal point of this article, we will take the discussion forward. Lajja Gauri is basically kept as an important symbol of good luck, fertility and reproduction. Bolon (1997)

By the way, in different parts of India (Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh), there is variation in the appearance of Lajja Gauri, but the recognition is the same. These idols can be divided into four classes (1. Utnapada pot, 2. Without arms and lotus-faced, 3. Lotus-faced with arms, 4. Anthropomorphic)

The construction period of this figure is being estimated from the second to the eleventh century, in which the initial construction of the seventh century is considered to be the most complete. In relation to Indian craft science, T.A. Gopinath Rao and J.N.Banerjee have compiled an explanation on the basis of mythological texts, but Lajja Gauri's formal explanation could not be obtained from anywhere. Symbols in Indian art are depicted in an interpretive manner. But the journey from the symbolic to the explanatory there is a long gap in between. To understand the relation between these two, “F. D.K. Boss" has spoken of 'morphological similarity' or 'similarity explanation'. (Boss-1960) As some scholars say, this figure is an evolved form of Srivatsa.

The allegorical interpretation of Lajja Gauri has been associated with many more figures (lotus, pitcher, frog and Srivatsa). Some of which will be discussed here.

· Lotus

Lotus is seen as a symbol of culture in Indian art. This lotus is always oriented towards the sunlight, hence it is considered a symbol of a worshiper of light (Singh, 2014). Because of the origin of Brahma from the lotus, the lotus is also considered a symbol of Brahma. It is also a symbol of creation. Brahma and Maa(Lajja Gauri) are considered identical as both are seen as the creators of the universe.

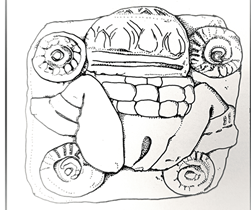

Lotus is depicted with the most important role in Lajja Gauri figure. In the initial phase, the upper part of the waist with the Uttanapada Asana is designated as Stupika shape on which the lotus shape is engraved (Figure 1). Here the stupa can be a symbol of the womb and the lotus can be seen in many ways depending on the Indian mythological belief. Lotus has been engraved in different ways mixed with this figure. The lotus, however, is seen as Lakshmi, and as it blooms and closes with sun light, it is seen as the light and the sun. But the full development of the bud of the lotus flower, withering and turning into a fruit shows the continuity of the universe. The place of lotus is ubiquitous in Indian iconography, poetry and literature (Varanasi- 2018).

· Potor Bhadrakalsha

According to the Vedic culture, Poornaghata or Bhadrakalasha was seen as the best auspicious symbol Agrawala (1966). In the Indian tradition, an urn filled with water is denoted as Srishti. In Hindu tradition, it is very necessary to have Kalash in any worship. The Kalash is filled with water, in which some flowers, coin and a betel nut are put, and a mango sprig is placed on top of it. This was probably the place of lotus. On top of the sprig a small vessel filled with some rice, and fruit or lamp was placed on the top. This tradition is the gift of Vedic culture; perhaps later it would have been established in the form of Lajja Gauri. Sankalia (1960)

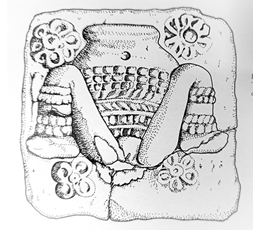

In this seated figure in the Uttanapada posture, the pitcher is represented as a part above the waist. Whose upper part is shown as a fully developed lotus? (Figure 2) In Indian culture, the pitcher is given as a symbol of good luck to the girl at the time of marriage, along with farewell. The pitcher is seen as a symbol of the world and also as the body of a living being. Another figure in this series representing the Uttanapada posture with only the pitcher in the form of a square strip. A four-leaf flower has been made under its right leg and a five-leaf flower under the left leg, which is made of seven leaves above the right knee and eight leaves above the left knee. This should be considered a symbol of continuous growth. Sinha (2010)

· Frog

We find a unique sculpture of Lajja Gauri dating back to the 2nd century in the Victoria and Albert Museum in Mathura Bolon (1997). This figure made of terracotta is so small that it comes in the palm (Figure 5). Its specialty is that the figure has been engraved on it from both the sides. On one side, the full statue of Lajja Gauri is seen, which is depicted in Uttanpad posture with both hands raised upwards. In this engraving with a face, the eyes and nose are clear but the mouth is not visible. The part below the waist of this figure of Lajja Gauri has been armed, but there is a lack of clothes in other figures, on the other side a figure of a frog is engraved with two raised eyes clearly visible. The arms and legs are jointly depicted for both sides in this figure. This figure has been compared to Heact, a goddess from Egypt. Who has the head of a frog and the body of a woman? The similarity is not only morphological, but it is believed that the goddess is worshiped for fertility in Egypt.

· Srivatsa

The tradition of marking symbols has been going on since ancient times, their transformation into idols is the result of religious movement. Srivatsa is also one of the auspicious symbols which were visualized in idols or were included in 'statue-signs' Agrawala (1966). Srivatsa was a popular symbol (Figure 4), which literally means son of Sri; this is also mentioned by Bollon. It was made to sit in the lap of Mother Goddess as a child. It is a rough figure with no clear head, feet, hands Agrawala (1966). This symbol has special recognition in all Indian religions. This symbol has been inscribed on the chest in the making of idols of Jain Tirthankaras, Gautama Buddha and Vishnu (Elements of Hindu iconography). It is considered a symbol of human and vegetative fertility. A multi-figure ardhachipatra made of stone depicting a lotus-headed goddess from Peddamudiyam (Figure 8) is attested as Srivatsa. On the basis of morphological similarity, it is seen as Lajja Gauri. Lajja Gauri can be compared with Sri in the six forms of Gauri Bolon (1997).

The association of Srivatsa with Lajja Gauri is seen on the basis of symbolic interpretation, as well as the similarity exists in the conjunction of both. The adumbration of the Srivatsa is similar to that of Lajja Gauri, whereupon it is said that in the Srivatsa is the appearance of Lakshmi or the Srivatsa is the symbol of Lakshmi Bolon (1997). But the statement of Vasudev Saran Agarwal is different from this, as mentioned above. Banerji (1998)

5. The Aesthetic and

significance of Lajja Gauri in Indian Art

The depiction of Lajja Gauri typically includes the amplification of reproductive symbols like as breasts, hips, and vulva. The exaggerated features serve as symbols of prosperity, vigor, and the potent creative force of reproduction. The focus on these physical characteristics in art aims to elicit a feeling of admiration and respect for the creative power embodied by Lajja Gauri. Tantric art and folklore traditions often depict Lajja Gauri with sensual and passionate imagery. These aesthetics represent concepts of energy, vitality, and the combination of masculine and feminine forces in the act of creation. Such imagery's visual allure lies in its ability to elicit innate instincts, intense emotions, and the unrefined vitality of fertility ceremonies and traditions. Lajja Gauri, while depicted with sexual images, is also closely associated with humility and shyness. This juxtaposition in art generates an enigmatic and captivating ambiance, encouraging reflection on the dichotomy between human nature and celestial forces. The juxtaposition of modesty and fertility symbolism in the artistic portrayal enhances the depth of meaning and encourages viewers to delve into profound philosophical and spiritual topics.

The aesthetics of Lajja Gauri in Indian art are closely connected to the reasons and symbolism associated with this deity. The use of exaggerated fertility symbols, sensual imagery, allegorical depictions, and ritualistic elements communicates themes of energy, abundance, divine unity, and the holiness of creation in Lajja Gauri art. The aesthetic components of Lajja Gauri art augment its visual impact and spiritual significance, encouraging spectators to reflect upon the profound connotations and enigmas surrounding fertility, life force, and the cosmic arrangement. Berkson (2009)

6. Conclusion

Within the context of modern Hinduism, Lajja Gauri is a goddess who is still relevant and alive despite the fact that she is steeped in old traditions. The research studies denotes that the worship of Lajja Gauri has adapted to modern sensibilities and analysis her role in resolving concerns like as fertility, childbirth, and women's empowerment in current culture. Specifically, the research focuses on the methods in which Lajja Gauri addresses these topics. In conclusion, the study of Lajja Gauri provides a fascinating peek into the intricately woven fabric of Hindu culture and mythology. Religious traditions are characterized by their dynamic aspect, which is highlighted by the symbolism, rituals, and evolving relevance of the god. By gaining knowledge of Lajja Gauri within the framework of its historical and cultural context, we are able to get significant insights on the intricate relationship that exists between mythology, symbolism, and the actual experience of religion. The sacred figure of Lajja Gauri has many mysterious composite figures as described by the scholars and authors. These figures are found in Indian subcontinent, specifically in Deccan. In study we can observe that from local village to royal temple in urban areas we can find mother goddess. The development of her figure from abstract to anthropomorphic form has come long way in the Indian subcontinent.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Nagarjunakonda (a), Guntur District, Andhra, Archacological Museum, Nagarjunakonda, 2 x 2 Inches, Terra-Cotta, Third- Fourth Century Courtesy Form of the

Goddess Lajja Gauri in Indian Art |

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Ter, Osmanabad

District, Maharashtra, Ter Museum 785, Size?,

Terra-Cotta, Third-Fourth Century Courtesy Form of the Goddess Lajja Gauri in

Indian |

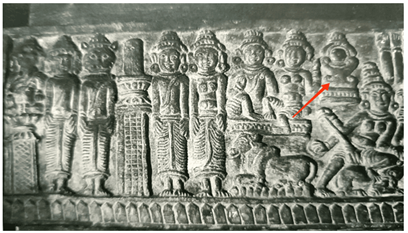

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Karlapalem, Gamtur

District, Andhra, Victoria Jubiler Museum,

Vijayawada, 19 x 10 Inches, Stone, Third- Fourth Century Courtesy Form of the

Goddess Lajja Gauri in Indian Art |

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Mathura, Mathura

District, Uttar Pradesh, Victoria and Albert Museum 177, Height 35 Inches,

Terra-Cotta, Second Century Courtesy Form of the

Goddess Lajja Gauri in Indian Art |

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Sri Lanka, Srivatsa, British

Museum 1898. Bronze, Height 5.5 Inches,1000 B.C. Courtesy Form of the Goddess

Lajja Gauri in Indian Art |

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Enadi, Tanjore District, Tamil Nadu,

Government Museum, Madras 39/35, Bronze, 2 x 1½ Inches, Ninth Century Courtesy https://www.sanatan.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2019/06/Srivatsa.jpg |

Figure 7

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Peddamudiyam, Cuddapah District, Andhra Pradesh,

Government Museum, Madras 17, 10 X 16½ Inches, Stone, Fourth Century Courtesy Form of the

Goddess Lajja Gauri in Indian Art. |

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Agrawala, V.S. (1966). Bhartiy Kala. Prithvi Prkasan, B 1/122, Dumrawn Kothi, Assi, Varanashi-5.

Banerji, R. D. (1998). Eastern Indian School of Medieval Sculpture. Archaeological Survey of India.

Berkson, C. (2009). Indian Sculpture: Towards the Rebirth of Aesthetics. Abhinav Publications.

Bolon, C.R. (1997). Form of the Goddess Lajja Gauri in Indian Art, Motilal banarsidass,41 U.A. Bungalow Road, Jawahar Nagar, Delhi 110007.

Fane, H. (1975). The Female Element in Indian Culture. Asian Folklore Studies, 34, 1, 51-112. https://doi.org/10.2307/1177740

Gupta, S. P. (2011). The Roots of Indian Art. Delhi B. R. Publishing Corporation, Delhi- 110052.

Mishra, D. (2017). Emergence and Development of Symbols in Indian Art (Bhartiya Kala me Prtikon ka Udbhav Yvam Vikash). State Institute of Education, Allahabad.

Pattanaik, D. (2000). The Goddess in India, The Five Faces of the Eternal Feminine. Rochester, Vermount: Inner Traditions International.

Sankalia, H.D. (1960). The Nude Goddess or 'Shameless Woman' in Western Asia. India, and South Eastern Asia. ArtibusAsiae, 23, 111-23. https://doi.org/10.2307/3248072

Singh, K. K. (2014). Bhartiya Kala or Prtik, Artistic Narration, Vol.VI, 12.

Sinha, G. (2010). Voices of Change 20 Artist, New Delhi: Marg Publication, Delhi.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.