ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

The Etymology of Public Space- Exploring crafting community spaces

Dr. Pankaj Chhabra 1![]()

![]() ,

Amrita Shukla 2

,

Amrita Shukla 2![]()

![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of Architecture, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar,

Punjab, India

2 Associate

Professor, Architecture Department, GITAM School of Architecture, GITAM University,

A.P. India., Research Scholar, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The nature of

public space has changed over the time period. Its

role evolved and developed as per the requirement, context, and culture of

people. Public space development is an art of creating a connection between

the city and people. A city without public spaces creates a city without

culture and history. Public space directly contributes for socio, the

economic and environmental development of the city. Its traces can be found

from Agora’s in the Greek period to parks and squares in contemporary times.

Public spaces have been focal point of the city in past, but they lost their

attention during modern urban development.

It acts as a stage for translation of art and the drama of city life.

Different experts from various fields have introduced different terminologies

to explain the same and much work is done on the environmental and economic

dimensions of sustainability. In contrast, the social dimension is yet to be

explored. The public space directly contributes to

social sustainability thus, it’s essential to understand and integrate the

concept of public space in the present time. In developing countries, the

shortage of public space can be addressed by its effective utilization and

the city’s identity can be restored by developing an association between the

city and people through publicness criteria identified in the study. The

intent of the study is to provide a solution to fill the social gap created

during modernism and technological advancement by taking references from the

past. |

|||

|

Received 21 March 2024 Accepted 24 June 2024 Published 29 June 2024 Corresponding Author Dr.

Pankaj Chhabra, pankaj.arch@gndu.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.1038 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Public Space, Vernacular, Sustainability, Public

Realm, Urban Public Space |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The term

etymology was derived from the Greek word etymon which means "the literal

meaning of a word as according to its origin.". The Etymology of public

space in the paper can be defined as understanding the meaning of public space

from its origin and development. The Oxford English dictionary defines public

as an adjective “concerning all people or open to all.” Public space is

distinctly defined in varied literature. Public space is open to all common

people without ownership of individual or private organizations Madanipour (2015). It is also defined as a place with

free access, and opportunities for interaction Carmona (2010). It is a democratic space Pourjafar et al. (2018) with accessibility and inclusion as

major attributes Madanipour (2010). Public space is “space to which

normally people have unrestricted access and right of way”Atkinson (2003). Public space is always being built

due to socio-spatial connections Hatuka (2016).

Public spaces are one of the key factor in the formulation of a city and vital part of urban life Madanipour (2015). It acts as a stage for translation of art and the drama of city life. It helps in better connectivity, raising quality of life and property value, control over crime and catalyst for economic activity Mitchell & Staeheli (2009). The public spaces have their own distinct features such as associated history, cultural importance, revenue generation etc Spaces (2016). Three meanings are mentioned in the dictionary definitions of culture: the culmination of human effort, the process of progress, and the entirety of a way of life Madanipour (2016). The historic public places were integrated, functional part of city such as market place, streets, squares, plazas etc. and were not devised for recreational and relaxation purpose only Barnett (1995).

Public

spaces have evolved significantly over time, imitating the variation in the

social, cultural, and political structures and resulting into

different typology of public space. In ancient times, public spaces were evolved as a result of activity

such as shopping, religious ceremonies, or political activity. Few of the word

famous examples of ancient public spaces are the Greek agora, the Roman Forum,

and the Egyptian temple complexes. With the development of art and culture, its

impression was also found in the public space in the form of ornamentation and

decorations Moazzeni et al. (2023).

Major change in the trends of public space were identified after

industrial revolutions. The encroachment of factories and mills raised the

alarm for place for people to relax and interact. The

public space in form of parks and plaza were

intentionally planned for usage by public. Overall, the evolution of public

spaces reflects the changing needs and values of societies over time, with a

constant tension between functional efficiency and aesthetic expression.

2. Literature Study

It has

been observed that ancient public places are not intentionally planned but they

were evolved between the buildings and its surrounding

as per art, architecture and culture. The daily activities and regional culture

serve as a self-reinforcing strategy for engaging in public life. The people

and events are dispersed over both time and space, that there is practically

never a possibility for individual actions to coalesce into larger or more

significant sequences of occurrences Olwig (1989). Public place is recognized as a

place made by the public for the public. The conception of public place alters

with the time Ramlee et al. (2015). “Nothing happens because nothing

happens” is result of scenarios where there are fewer people and less events

happening in public areas Safiullah (2018). Whyte discovered three main

factors for successful public spaces: accessibility, comfort, and sociability.

Marcus and Francis claim the most important factor for successful space is its

ability to accommodate multiple need

In past,

several activities were conducted simultaneously in open area which resulted in

stay of public more than required time, indicating a sense of association or

placeness and evolution of context specific public place Hajela (2021). The intent of the study is to

identify the dimensions contribution for the evolution and utilization of

public place.

3. Evolution of Public Spaces

3.1. The scenario of public spaces round the globe:

The

public space that lay at the heart of the polis and functioned as the hub of

the town as well as a venue for political gatherings began with the Greek Agora

Li et al. (2022), Thombre & Kapshe (2020). It was therefore important from a

political, social, and economic perspective. It provided a location for both

official and informal public gatherings Dickenson (2015). Private residences originally

surrounded the Agora, but over time, stoas, porticoes, covered walkways,

temples, and sanctuaries were added. In the later periods of Greek culture,

outdoor theaters and gymnasiums were constructed as well.

3.1.2. The Roman Forums

During

the Roman Empire, the agora and acropolis functions in Greece were merged into

one "forum." It was a semi-enclosed, enclosed space available for

trade, social gatherings, political, religious, and sporting events. Like

Agora, the forum was a public space dominated by the general

public. Forums were rectangular in shape and had a 2 to 3 ratio. The

Forums were enclosed by porticoes. The basilicas, marketplaces, stores, and

temples that were housed in the forums produced a fusion of religious and civic

structures. It included public baths and a theater, among other significant

recreational amenities Activism Social (n.d.). It also functioned as the site of

curia and comitium, or city council and political sessions, respectively.

3.1.3. The Medieval marketplace

The

marketplaces were created in the eleventh century, and during medieval era it

became a prominent public space. The medieval markets were situated at the

intersection of prominent throughfaresActivism Social (n.d.). They were generally found in front

of the cathedral, and in the heart of the town. It was surrounded with workplace such as workshop, storage area, and place for

trade. It was a regular place for common people to interact with the visitors.

Culturally,

marketplaces were significant for the exchange of ideas and customs,

particularly in trade hubs that connected diverse regions. Markets often

coincided with festivals, attracting larger crowds and offering additional

entertainment. Despite their benefits, marketplaces faced challenges like

vendor competition, which sometimes led to conflicts, public health risks from

crowded conditions, and prevalent theft and fraud.

The

medieval marketplace was a multifaceted institution essential to the economic,

social, and cultural life of medieval towns. The marketplace was not only an

economic hub but also a dynamic public space where social, cultural, and

communal activities thrived, reflecting the complexity and vitality of medieval

urban life. It facilitated daily transactions, fostered community interactions,

and enabled cultural exchanges, reflecting the dynamic nature of medieval

society.

3.1.4. The Renaissance Plaza

The

Renaissance Plaza, used to be surrounded by the town hall, the cathedral, and

other important building Langstraat & Melik (2013). The plaza was the place for the

people to gather and have open-air celebrations. It was prominent

place for racial, religious, and political activities along with the plays and

other theatrical performance. The majority of it had

symmetrical shapes in its design. A cohesive facade on the buildings encircling

the Plaza and the squares highlighted the importance of harmony and balance in

architectural design. Furthermore, this design feature led to the development

of affluent residential neighborhoods around the squares, which opened the door

for a unique semi-public character Varna. (2011). New residential neighborhood

designers also began to favor this innovative way of controlling public access

to the plaza.

3.1.5. Public Space in Modern Era

There has

been a sharp shift into the modern era public space since the renaissance

plazas. Rapid mobility in cities shaped urban development and fostered a close

relationship between the surrounding construction area and open space. On the

other side, there were development of new typology of

public spaces for leisure and entertainment. In the 19th century modified and

new public space came into existence, they were modified space for buying like

shopping malls and arcades Varna. (2011).

3.2. The scenario of public spaces in Indian cities

In the

past, public areas in Indian cities were thriving hubs of social, commercial,

and cultural activity. As said by Sharon Zukin “Public spaces are window in

city’s soul.” The public spaces included crowded marketplaces, courtyards in

temples, and town squares where people congregated for religious ceremonies,

festivals, public gatherings, and trade. These kinds of places encouraged a

sense of community and promoted interaction amongst people from various social

classes. They were frequently embellished with elaborate architecture and works

of public art that reflected the area's rich cultural legacy. In addition to

being essential to daily existence, these areas were also vital to the social

and cultural cohesiveness of ancient Indian cities.

3.2.1. Ghats

Ghats are

an example of an approach of settlement at place where

interaction between land and water happens along the banks of the river. It was

created to access the varying water levels in different seasons Varma (2011). Ghats are vibrant public space

with amalgamation of daily activities, religious rituals, commercial trade,

celebration, cremation, cultural activities, and communal norms around the

ecology.

Ghats of

Varanasi are outstanding example of interaction

between the natural and urban elements. Varanasi ghats are thin silver line of

public space between dense city and the river Ganga Sinha (2020).

3.2.2. Chaupars and chowks

Chaupals are integral public space of city from ancient time. The

square formed after intersection of roads is known as

chaupars. These are gathering and social interaction place for public built

around water distribution system and supported by other ancillary activities of

everyday life in adjoining surrounding.

On

special occasions, the badi chaupar in Jaipur is used for public gathering. They are three times wider than road width. It has underground aqueducts and street-level

drinking water sources. Chaupar now contains some of the largest bazaars,

including Kishanpole Bazar and Gangauri Bazar. These markets are in harmony

with the city's important temples and Havelis. The Chaupar's 100 × 100 m

footprint allowed for four-way automobile traffic in addition to supporting

substantial pedestrian activity.

A tree by

the chowk encourages interaction while providing a sense of security and

comfort. People living there are encouraged to feel safe by seeing people

chatting and interacting with one another in their free time at the main chowks

of the town or location. As they serve as the neighborhood's "eyes on the

street," it lowers the likelihood of crime Gupta et al. (2019).Manek Chowk in Ahmedabad is an good and live example of public space Shukla & Navratra (2017).

3.2.3. Streets and Pols

Historically,

streets have served as the focal point of towns and cities. Mobility, trade,

and social contact have historically been the three principal uses of streets.

The street, which is typically defined as a public area with residences,

businesses, and other structures on one or both sides, serves social and

economic purposes that are essential for urban life Warah (2013). Instead of being a function of the

economy, streets in ancient towns were the product of a vision of civilization.

The

residential lanes of Ahmedabad's walled city were known as "pols," and they frequently came to closed-off areas

known as "chowks," which were heavily used for both social

interaction and business. The street itself served as a gathering place for the

neighborhood because the houses surrounding the street had steps facing the

street called "otlas" where people could sit and observe street life.

3.2.4. Indian Bazar

Most of

the general public used bazaars as gathering place and adorn the same on festivals and event. In old days, these areas had a highly organic and dynamic

quality. When designing public areas, the combination of formal and informal

settings was given careful consideration. They are important commercial

and cultural spaces and promote quality of life within cities Congress Indian History (2018).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Ancient Public Space, its Function, and Characteristics |

|||

|

Public Space |

Purpose/Function |

Location |

Characteristics |

|

Agora |

Market, political, social |

Ancient Greek city-states |

Central gathering place; symbol of democracy and

civic pride; near important civic and religious buildings |

|

Forum |

Market, political, legal, social, athletic |

Ancient Roman cities |

Central square; symbol of Roman power and

civilization; near political and religious buildings. |

|

Medieval Market |

Commerce, culture, social |

European medieval towns |

Bustling, vibrant space; important center of

commerce, culture, and social life; located in town square. |

|

Plaza |

Social, cultural, political, entertainment |

European cities |

Public square or open space; gathering place for

social, cultural, and political events; may be used for public markets or

entertainment. |

|

Ghats |

Religious, ritual |

Indian cities and towns |

Series of steps leading down to body of water;

important religious site; used for bathing and other religious activities. |

|

Chaupars and Chowk |

Social, cultural, religious |

Indian cities and towns |

Small public squares or intersections; gathering

places for social, cultural, and religious events; surrounded by shops and

vendors. |

|

Street and Pols |

Commerce, culture, social |

Indian cities and towns |

Narrow, winding lanes; important social and cultural

spaces; lined with small shops and vendors. |

|

Indian Bazaar |

Commerce, culture, social |

Indian cities and towns |

Vibrant marketplaces; important centers of commerce

and culture; noisy, colorful, and crowded; vendors sell a wide variety of

goods and food. |

The study

from literature review can be summarized in matrix as following.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Categorization of Ancient Public Space Based on Function. |

|||||||

|

S. No |

Public space |

Festival/

cultural |

Political

identity/ meeting |

Commercial

activity/ trade |

Religious

purpose |

Athletic |

Socializing |

|

1 |

Agora |

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

o

|

·

|

|

2 |

Forums |

o |

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

3 |

Market |

o |

o

|

·

|

o

|

o |

·

|

|

4 |

Plaza |

·

|

·

|

o |

·

|

o

|

·

|

|

5 |

Ghats |

·

|

o |

·

|

·

|

o

|

·

|

|

6 |

Chaupal and

chowks |

o

|

·

|

·

|

o

|

o

|

·

|

|

7 |

Street and pols |

·

|

o |

·

|

o

|

o

|

·

|

|

8 |

Bazar |

·

|

·

|

·

|

o

|

o

|

·

|

The

matrix provides clear interpretation about multi functionality, socio-cultural

and economic aspects of public space. Along with socialization, there were

secondary activities associated with the space such as festival celebration,

cultural and political procession, trading, athletics etc.

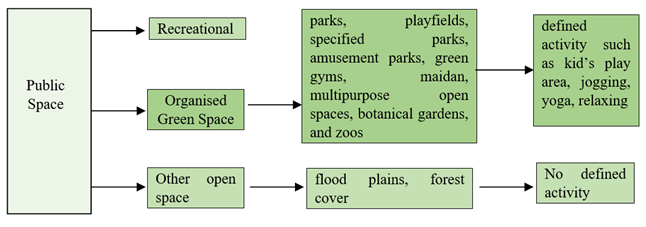

3.3. Contemporary classification of public spaces

Open

spaces are classified into following three categories

by city development plan i-e: Recreational space, organised green space and

other open spaces. As per URDPFI, there is no defined definition for

recreational space where as organised green space is categorised as parks,

playfields, specified parks, amusement parks, green gyms, maidan, multipurpose

open spaces, botanical gardens, zoos, and traffic parks and vacant lands/open

spaces including flood plains, forest cover, etc. in plain areas are listed under

other open spaces Gujar et al. (2022), Ministry of Urban Development

(n.d.).

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Contemporary Classification of Public Spaces |

3.4. Culture and public space

Since

ancient time, the city has expanded naturally and

refined on its own. The existing road system, around which the public space was

organized, played a significant role Siláči & Vitková (2017). It should be noted that cities

vary greatly from one another in terms of scale, planning pattern, social

norms, and cultural traditions Hatuka (2016). Thus characteristics of public

areas vary by province and culture Pietro

Garau (2015). Public places are crucial for practicing

human rights, especially for the exercise of cultural rights. Social life act as nuclei of public spaces. The built environment and

public are closely related Hajela (2021).

Festivals

and events have a long history of being taking place

in public areas of cities. Traces are found in the ghats of Varanasi, chaupals

of Jaipur, religious precincts of Ujjain and Madurai, or in the streets of

Nagpur. In recent years, this trend has become more prevalent. Festivals and

events are used by cities to advance economic development goals,

and promote social cohesion and cultural involvement Union European. (2020).

Over ages, development takes place at all level

of cultural code i-e from macro to micro practices. However, the pattern of use

of public places has undergone a significant change due to the rapid

urbanization and the influence of modern culture. Previously, public places

were well-maintained by various community organizations, which have gradually

begun to crumble, and quickly degrading. Since municipalities are ineffective

at preserving them, unplanned parking and several activities are constantly

intruding on them Pietro

Garau (2015).

Public place provides opportunity for cultural exchange whereas

culture encourages usage of public place. Both are strongly associated and are in separable.

Public

space is now more frequently used for alternate, pleasure activities rather

than for its original, utilitarian function. The dynamics makes it more

important than ever for spaces that are relevant, anticipated, and offer a

place for people to unwind, mingle, and participate in urban life Gehl & Matan (2009).

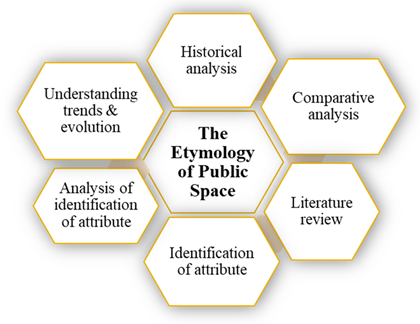

4. Methodology

The

methodology adopted for the study is historical analysis and comparative

analysis technique. It will help to identify the characteristics associated

with ancient public space. The Historical analysis is conducted by study of

historical records, like photographs, and written content to find the foot print of the transformation of public spaces over time.

The comparative analysis is conducted by analyzing public space of different

typology, time period and geographical location to

understand the progression of public space Siláči & Vitková (2017). The above said analysis helps in

identifying the trend and gradual evolution of public space over the time.

Extensive

literature study is conducted from different journals, books and website to

understand the setting and activities carried out in historical public space.

The identified attributes are than categorized under broad parameters based on

similarity of properties Praliya & Garg (2019). From the study conducted it could

be identified that public places from the past have different activities in

terms of necessary activity and optional activity along with opportunities to

socialize, supported by visual and physical accessibility and safety by

presence of people.

The

historical analysis provides insights into the changes in public spaces,

revealing how they have evolved to meet the needs of their users. The

comparative analysis allows for the assessment of public spaces across

different eras and regions, highlighting the similarities and differences in

their development. This dual approach not only identifies the trends in public

space evolution but also uncovers the factors driving these changes.

The study

reveals that ancient public spaces facilitated a variety of activities,

categorized as necessary and optional activities, and provided opportunities

for socialization. These spaces were characterized by their visual and physical

accessibility and the safety provided by the presence of people. By

understanding these attributes, the study sheds light on the essential

components that have historically contributed to the functionality and appeal

of public spaces. This comprehensive methodology thus provides a robust

framework for analyzing and understanding the evolution of public spaces over

time.

Figure

2

|

Figure 2 Methodology Chart |

5. Discussion and result

Ancient

public spaces were integrated component of the ancient

societies. It providing a platform for public to associate, interact, business, and engage in

cultural and political activities. The public spaces served as nuclei for

community life, bringing people together and developing sense of belongingness.

It invited people from diverse background, age group,

ethnicity, class to interact and exchange idea. Ancient public space clearly

outlines the characteristics for inclusive public space.

Public

spaces also played an important role in promoting civic engagement and participation.

They were often used for political gatherings, where citizens could voice their

opinions and participate in decision-making processes. This helped to create a

more democratic and participatory society, where people felt empowered and

engaged in the political process.

However,

ancient public spaces also had their weaknesses. For example, they were often

designed to cater to the needs and interests of a particular group, such as the

ruling elite or the dominant cultural group. This could lead to exclusion and

marginalization of certain groups, particularly those who were not represented

in the decision-making process.

Another

weakness was the potential for public spaces to become sites of conflict and

violence. Because they were often used for political gatherings and

demonstrations, they could be a target for those who sought to disrupt or

challenge the status quo. This could lead to tensions and conflicts that could

spill over into the broader society.

Overall,

the strengths and weaknesses of ancient public spaces depended on how they were

designed, managed, and used. When designed with inclusivity and democratic

participation in mind, they could be a powerful force for social cohesion and

civic engagement. However, when they were exclusive or became the site of

conflict and violence, they could undermine social harmony and democratic

participation.

Ancient

public places were often located at the center of a city or town,

and were easily accessible to the public. They were designed to

accommodate large gatherings of people for various purposes such as religious

ceremonies, political assemblies, markets, entertainment events and often had

symbolic value, representing the power and prestige of the ruling class or a

particular religious institution. Ancient public open spaces were sometimes

designed with symbolic elements that reflected the values and beliefs of the

society. For example, the ancient Greeks often used statues and monuments to

honor their gods, heroes, and important historical figures. They were also

equipped with infrastructure such as seating and water sources. Ancient public

open spaces served a variety of purposes and were designed with different

approaches depending on the culture and time period.

However, they often reflected the values and priorities of the society that

built and used them, and they continue to influence urban design and planning

today.

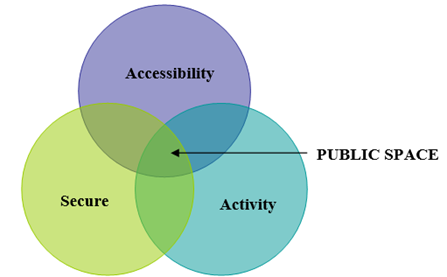

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Attributes Identified from Ancient Public Space for Successful Public Space |

6. Conclusion

Public

places often played an important role in the cultural life of ancient

societies. They were venues for festivals, games, and religious ceremonies, and

they also served as centers for education and intellectual discourse

Today,

many ancient public spaces continue to serve as important cultural and

historical landmarks, attracting visitors from around the world who come to

learn about the people and civilizations of the past.

Ancient

public places were often designed to serve multiple functions.

Public

places were important for fostering social cohesion and community identity.

They provided a space where people could come together to share experiences,

exchange ideas, and build relationships with others.

Social

interaction:

Ancient public spaces were designed to encourage social interaction and

exchange of ideas. People gathered there to buy and sell goods, discuss

politics and religion, and participate in cultural events. Today, we can use

this knowledge to design public spaces that foster social interaction and

community building.

Urban

design: Ancient

public spaces were often designed with a clear purpose and function. For

example, marketplaces were designed for commerce, while forums were designed

for public discourse. Today, we can use this knowledge to design public spaces

that are purposeful and serve the needs of the community.

Sustainability: Ancient public spaces were often

built to last and were designed with natural materials and methods that were

environmentally sustainable. Today, we can learn from these practices to create

public spaces that are environmentally sustainable and resilient.

Cultural

identity: Ancient

public spaces were often a reflection of the cultural identity and values of

the community. Today, we can use this knowledge to design public spaces that

reflect and celebrate the diversity of cultures and communities.

The

role of public art:

Many ancient public spaces featured sculptures, paintings, and other works of

art. These pieces were often used to convey important messages or to celebrate

cultural achievements.

The

importance of community: Ancient public spaces were central gathering places for people to meet,

socialize, and exchange goods and ideas. These spaces fostered a sense of

community and belonging, which is still important today.

Finally,

ancient public spaces can teach us about the importance of public participation

in governance. Many ancient societies held public meetings and debates in these

spaces, providing a forum for citizens to voice their opinions and influence

political decision-making. This is a valuable lesson that we can apply to our

own democratic systems today, as we work to create more inclusive and

participatory forms of governance.

Overall, learning from ancient public spaces can provide valuable insights into how to create public spaces that are socially, culturally, and environmentally sustainable, and that serve the needs of the community.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Activism Social (n.d.). 'What Happened to

Public Space? A Quick Guide Through Europe 's History

The Beginning: The Greek Agora'.

Atkinson, R. (2003). 'Domestication by Cappuccino or a Revenge on Management of Public Spaces'.

Barnett, J. (1995). 'Urban

Places, Planning for the Use of Design Guide'. International Encyclopedia of

the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 16031-16035.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/04464-8

Carmona, M. (2010). Contemporary Public Space, Part Two:

Classification. Journal of Urban Design, 15(2), 157-73.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13574801003638111

Congress Indian History (2018). 'Bazar as a Contesting Public Space: Its Differeing Perceptions and Usage at Colonial

Cuttack Author (s): pramod kr. Mohanty Source:

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress , Vol . 68, PartOne (200), 1029-1040

Published by: Indian Histor'. 68(2007): 1029-40.

Dickenson, C. (2015).

'Looking at Ancient Public Space. The Greek Agora in Hellenistic and Roman

Times'. Groniek, 46(198), 85-95.

Gehl, J., & Matan, A. (2009). 'Two Perspectives on Public Spaces'. Building Research &

Information, 37(1), 106-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613210802519293

Gujar, S., Deshmukh, A., & Gupta, R. (2022). 'Review of Open Space Rules and Regulations and Identification of Specificities for Plot-Level Open Spaces to Facilitate Sustainable Development: An Indian Case'. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 1084(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1084/1/012073

Gupta, S., Sehgal, V., Rao, P., & Abdul, A. P. J. (2019). Analysing Chowk as an Urban Public Space a Case of Lucknow. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 4(6), 595-623.

Hajela, P. (2021). Dimensions of Public Spaces in Indian Market Places: Feeling through Human Senses, 11.

Hatuka, T. (2016). 'A Companion'. In Protest Culture, A Companion, ed. and Joachim Scharloth Kathrin Fahlenbrach, Martin Klimke. New York: Berghahn Books.

Langstraat, F., & Melik, R. V. (2013). 'Challenging the

"End of Public Space": A Comparative Analysis of Publicness in

British and Dutch Urban Spaces'. Journal of Urban Design, 18(3), 429-48.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2013.800451

Li, J., Dang, A., & Song, Y. (2022). Defining the Ideal Public

Space: A Perspective from the Publicness. Journal of Urban Management, 11(4),

479-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2022.08.005.

Madanipour, A. (2003). Public and

Private Spaces of the City. Routledge.

Madanipour,

A. (2010). Whose Public Space? International Case Studies in Edited by

Whose Public Space? (1st Ed). Oxon: Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203860946

Madanipour, A. (2016). 'Cultural Pluralism, Tolerance,

and Public Space'. Space and Pluralism: Can Contemporary Cities be Places of

Tolerance?, 35-54. https://doi.org/10.1515/9789633861264-004

Madanipour,

A., & Newcastle Tyne. (2015). 24 International Encyclopedia

of Social & Behavioral Sciences Urban Design and Public Space. (2nd Ed).

Elsevier. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.74049-9

Ministry of Urban Development (n.d.). 1 Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation (Urdpfi) Guidelines. http://moud.gov.in

Mitchell, D., & Staeheli, L. A. (2009). 'Public Space

Module 6'. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 511-16.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044910-4.00990-1

Moazzeni, A., Villalobos, M. H., & Eskandar, A. A. (2023). 'Sustaining Historic Cities: An Approach Using the Ideas of Landscape and Place'. ISVS-Journal of International Society for the Study of Vernacular Settlements, 10(1), 320-32.

Olwig,

K. R. (1989). 8 Landscape Journal Life Between Buildings: Using Public

Space. https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.8.1.54

Pietro Garau (2015). William Fernando Camargo. 2015. Global Public Space Toolkit: From Global Principles to Local Policies and Practice. (1st Ed).

Pourjafar, M. R., Zangir, M. S., Moghadam, S. N. M., & Farhani,

R. (2018). 'Is there any Room for Public? Democratic Evaluation of

Publicness of Public Places'. Journal of Urban and Environmental Engineering,

12(1), 26-39. https://doi.org/10.4090/juee.2018.v12n1.26-39

Praliya, S., & Garg, P. (2019). 'Public Space Quality Evaluation: Prerequisite for Public Space Management'. The Journal of Public Space 4(4/1), 93-126. https://doi.org/10.32891/jps.v4i1.667

Ramlee, M., Omar, D., Yunus, R. M., & Samadi, Z. (2015).

Revitalisation of Urban Public Space- A Review'. Procedia-Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 360-367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.187

Safiullah (2018). 'Beyond a Channel for Movement;

Inquest of Street Layerings in Urban Realm'. International Journal of Creative

Research Thoughts, IJCRT, 6(2), 369-73.

Shukla, A., & Navratra, N.D. (2017). Streets as Public Spaces: A Case Study of Manek Chowk. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology, 8(5).

Siláči, I., & Vitková, L. (2017). 'Public Spaces as

the Reflection of Society and Its Culture'. IOP Conference Series: Materials

Science and Engineering, 245(4). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/245/4/042009

Sinha,

A. (2020). 'Ghats on the Ganga in Varanasi: The

Making of Vernacular Landscape'. Heritage Conservation in Postcolonial India

(Figure 3), 221-34.

Spaces (2016). The Charter of Public. Charter of Public Space. Public Programme, United Nations Settlements, Human Nations, United Settlements, Human.

Thombre, L., & Kapshe, C. (2020). 'Conviviality as a Spatial Planning Goal for Public Open Spaces'. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE), 8(5), 4382-87. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.E7038.018520

Union European. (2020). Public Spaces: Culture and Integration in Europe.

Varma, A. (2011). 'Vishram Ghat, Mathura, India: A Conservation Model for Ghat Restoration in India'.

64.

Varna. (2011). 'Assesing the Publicness of Public Places:

Towards a New Model Department of Urban Studies'.

Warah, R. (2013). Streets as Public Space and Driver of Urban Prosperity. First. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

Zagroba,

M., Szczepańska, A., & Senetra, A. (2020). Analysis and

Evaluation of Historical Public Spaces in Small Towns in the Polish Region of

Warmia. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(20), 1-20.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.