ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Crafting Indian Markets: The art of Blurring the boundaries of publicness Case of Delhi

Dr. Pankaj Chhabra 2![]()

![]() ,

Simranpreet Kaur 1

,

Simranpreet Kaur 1![]()

![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of Planning and Architecture, Guru Nanak Dev University,

Amritsar, Punjab, India

2 Research

Scholar, Department of Planning and Architecture, Guru Nanak Dev University,

Amritsar, Punjab, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The urban landscape of India is crafted by bustling

markets that have long served as vibrant hubs of commerce, social

interaction, and cultural exchange. However, the dichotomy between public and

private ownership within these markets has become increasingly blurred, as

private shopkeepers and vendors encroach upon spaces originally designated

for community use. This research paper delves to explore the nuanced

dimensions of this phenomenon, shedding light on orchestrating transformation

of ostensibly public spaces into privatized domains and the ensuing impact on

the public realm. The central objective of this study is to initiate a

meaningful dialogue within the public domain regarding the ever-crafting

nature of public spaces in India, particularly in the context of

marketplaces. The encroachment by private entities poses critical questions

about the essence of publicness in these spaces, challenging traditional

notions and raising concerns about the equitable access and shared ownership

of urban areas. The paper employs a multi-disciplinary approach,

drawing on urban sociology, anthropology, and urban planning theories to

unravel the layers of complexities involved in the art of privatizing these

public spaces. Through an extensive review of literature, case studies, and

field observations, the paper aims to provide a comprehensive understanding

of the dynamics at play and the various stakeholders involved in this

process. Designing the newly-evolved socio-economic

system around these community spaces is the real

social art. Key thematic areas explored in this research include

the historical evolution of urban markets in India, the socio-economic

motivations driving private encroachments, the role of municipal authorities

in regulating public spaces, and the impact on the community's right to

access and enjoy these spaces. Additionally, the study delves into the legal

frameworks governing public spaces and the effectiveness of current

regulatory measures in curbing privatization tendencies,

but is restricted to examining the administrative changes and market

transformations in Delhi, and does not concentrate on socio-cultural changes,

which is a detailed area of focus on its own. By fostering a dialogue on the

publicness of public spaces, the research aims to stimulate awareness and

encourage civic engagement in crafting the future of urban landscapes with

delicate artistry. The findings of this study are expected to inform

policymakers, urban planners, and community leaders, offering insights into

potential interventions to reclaim and preserve public spaces for the

collective benefit of society. In conclusion, this research paper contributes to the

growing body of knowledge on urban dynamics in India and serves as a catalyst

for reimagining and revitalizing public spaces. The implications of this

study extend beyond academia, resonating with citizens, activists, and

policymakers alike, and public perceptions to ensure the preservation and

enhancement of the publicness of these vital urban spaces, as they

collectively strive to strike a balance between the imperatives of commerce

and the preservation of shared, inclusive urban spaces. |

|||

|

Received 19 March 2024 Accepted 02 June 2024 Published 07 June 2024 Corresponding Author Simranpreet

Kaur, ar.simranpreet@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.1030 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Indian Markets, Public Spaces, Publicness,

Privatization, Transformation |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background and Context

Indian markets have a rich and vibrant history deeply ingrained in the socio-cultural fabric of the nation. From ancient times, markets have served as pivotal nodes of economic activity, social interaction, and cultural exchange. The bustling bazaars of India, with their kaleidoscope of sights, sounds, and smells, epitomize the essence of public spaces, where people from diverse backgrounds come together to buy, sell, and engage in myriad interactions. The concept of publicness in Indian markets is deeply rooted in the idea of shared spaces where individuals from all walks of life converge, transcending boundaries of caste, class, and religion. These markets have traditionally been open and accessible to all, embodying principles of inclusivity, diversity, and communal ownership. They not only fulfil the basic needs of daily life but also serve as sites for socialization, cultural expression, and community cohesion.

However, over time, the landscape of Indian markets has undergone significant transformations, influenced by various socio-economic, political, and cultural factors. Rapid urbanization, globalization, and changing consumer preferences have led to the emergence of new market forms, characterized by modern retail outlets, shopping malls, and online platforms. In parallel, the traditional markets, often situated in the heart of cities and towns, have faced challenges stemming from encroachments, infrastructure deficiencies, and regulatory constraints.

The publicness of Indian markets, once taken for granted, has come under threat due to the encroachment of private interests into spaces originally designated for public use. Private shopkeepers, vendors, and commercial establishments have increasingly appropriated public spaces for their own benefit, blurring the boundaries between public and private realms. This phenomenon raises critical questions about the equitable access, shared ownership, and democratic governance of urban spaces, challenging the fundamental principles of publicness and urban citizenship.

In this context, understanding the dynamics of privatization in Indian markets becomes imperative. It involves unravelling the complex interplay of economic forces, institutional arrangements, and socio-cultural dynamics shaping the transformation of public spaces into privatized domains. Moreover, it requires a nuanced examination of the implications of such privatization for marginalized communities, informal sector workers, and the broader urban population.

As India

grapples with the challenges of urbanization, it is essential to critically

engage with the evolving nature of public spaces and reaffirm their role as

vital components of inclusive, sustainable, and democratic cities. By delving

into the historical evolution, socio-economic dynamics, and regulatory

frameworks governing Indian markets, we can gain insights into the complexities

of publicness and pave the way for meaningful interventions aimed at reclaiming

and revitalizing these crucial urban spaces for the collective benefit of

society.

1.2. Problem statement

Rapid urbanization, coupled with evolving consumer preferences, has led to a shift in the landscape of traditional marketplaces. Encroachment by private entities, including shopkeepers and commercial establishments, onto spaces originally designated for public use, has become a pervasive issue. This encroachment not only blurs the distinction between public and private realms but also undermines the fundamental principles of publicness, equity, and democratic governance in urban spaces. Moreover, the privatization of public markets raises concerns about access, inclusivity, and the preservation of cultural heritage. Marginalized communities and informal sector workers are disproportionately affected by these changes, facing challenges in livelihoods, access to space, and participation in economic activities. As Indian markets continue to undergo transformation, understanding and addressing the dynamics of encroachment and privatization emerge as critical imperatives for fostering inclusive, sustainable, and vibrant urban environments

1.3. Objectives of the study

The central

objective of this study is to initiate a meaningful dialogue within the public

domain regarding the evolving nature of public spaces in India, particularly in

the context of marketplaces in Delhi. The encroachment by private entities

poses critical questions about the essence of publicness in these spaces,

challenging traditional notions and raising concerns about equitable access and

shared ownership of urban areas. The methodology focuses on generic data

analysis on shift in pattern of urban markets and their challenges to more

specific legal framework and regulations, and its impact on the community. The

study also involves case study of Delhi’s oldest market Chandni Chowk and its

transformation in the year 2021.

2. Historical evolution of urban markets in Delhi

2.1. Origin and significance and shift in pattern over time

The

historical evolution of Indian markets is deeply rooted in the country's rich

cultural and economic history, spanning thousands of years. Ancient India was

renowned for its bustling marketplaces, where goods from across the

subcontinent and beyond were traded. The Harappan civilization, for instance,

boasted well-organized market centres in cities like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa,

showcasing the early roots of commerce in the region Kenoyer (1998).

During the

medieval period, Indian markets flourished under various dynasties and empires,

such as the Mauryas, Guptas, and Mughals. These

rulers patronized trade and commerce, leading to the establishment of vibrant

market towns and bazaars across the subcontinent. The Grand Trunk Road, for

instance, facilitated trade between different regions, fostering the growth of

markets along its route.

Colonial rule

brought significant changes to Indian markets, with the British East India

Company exerting control over trade and commerce. The Company established

trading posts and monopolies, reshaping traditional market networks and

integrating India into the global economy Roy & Mandal (2002). Colonial-era cities like Calcutta

(Kolkata) and Bombay (Mumbai) saw the emergence of new marketplaces catering to

British colonial interests.

Post-independence,

India witnessed rapid urbanization and economic development, leading to the

transformation of traditional markets. Delhi, as India's capital and a major

urban center, experienced significant changes in its

market landscape. The advent of modern retail formats, such as shopping malls

and supermarkets, alongside the persistence of traditional bazaars like Chandni

Chowk and Sarojini Nagar, reflects the complex evolution of markets in the city

Varman & Khare (2017).

Overall, the

evolution of markets in Delhi mirrors the broader trajectory of Indian markets,

showcasing a blend of tradition and modernity. While traditional bazaars

continue to thrive, modern retail formats have also become integral to the

city's commercial landscape, highlighting the resilience and adaptability of

India's marketplaces in the face of changing times.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 A Hustling

Day in Chandni Chowk Market Source Google

Images |

3. Socio-Economic Motivations Driving private encroachments

3.1. Challenges faced by traditional vendors v/s Economic incentives in private entities and its impact on overall livelihood

The

socio-economic motivations driving private encroachments in Indian markets are

multifaceted, with both traditional vendors and private entities navigating a

complex landscape shaped by various factors.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Crafts

Bazaar in Dilli Haat INA Source Google

Images |

For

traditional vendors, the challenges are manifold. Firstly, rapid urbanization

and changing consumer preferences pose significant hurdles. As cities expand

and modernize, traditional vendors often find themselves marginalized or

displaced due to infrastructural developments or zoning regulations,

Additionally, competition from modern retail formats and e-commerce platforms

further exacerbates their economic challenges, as they struggle to compete with

larger businesses in terms of pricing, marketing, and product diversity Roy & Mandal (2002). Furthermore, lack of access to formal

credit, limited bargaining power, and vulnerability to exploitation by

middlemen and authorities compound their difficulties Hashmi (n.d.).

On the other

hand, private entities are motivated by various economic incentives to encroach

upon public spaces in Indian markets. Firstly, the high profitability potential

of prime locations in bustling marketplaces drives private businesses to seek

control over these spaces Varman & Khare (2017). By establishing

their presence in prominent market areas, private entities can attract a larger

customer base and capitalize on the foot traffic generated by these locations.

Moreover, lax enforcement of regulations and corruption within municipal authorities

often incentivize private businesses to encroach upon public spaces with

impunity, knowing that legal consequences are minimal. Additionally, the

informal nature of many Indian markets, characterized by weak property rights and regulatory

oversight, provides fertile ground for private encroachments Chakraborty (2023).

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Handicraft

Market Inside Red Fort Post Interventions Source Google

Images |

Therefore,

the socio-economic motivations driving private encroachments in Indian markets

are deeply intertwined with the challenges faced by traditional vendors and the

economic incentives available to private entities. Addressing these issues

requires a holistic approach that considers the needs and rights of all

stakeholders involved while striving to maintain the vibrancy and inclusivity

of public spaces in urban marketplaces.

4. Role of Local/ Municipal Authorities in Regulating Public Spaces

4.1. Legal framework governing public spaces: analysis of laws and regulations

In the Indian

context, the role of local municipal authorities in regulating public spaces,

particularly in cities like Delhi, is crucial for maintaining order, ensuring

public safety, and preserving the integrity of urban spaces. The legal

framework governing public spaces in India encompasses various laws,

regulations, and policies at the national, state, and local levels.

The primary

legislation governing urban planning and development in India is the Town and

Country Planning Act, which empowers municipal bodies to regulate land use,

zoning, and construction activities within their jurisdictions TCPO. (2020). The context of public spaces,

municipal authorities are responsible for enforcing regulations related to

encroachments, unauthorized constructions, and street vending. The Delhi

Municipal Corporation Act grants powers to municipal bodies in Delhi to

regulate street vending activities, issue licenses, and designate vending zones

(Government of NCT of Delhi, 1957). However, enforcement of these regulations

often faces challenges due to factors such as limited resources, corruption,

and political interference Bhowmik (2003).

For example,

the unauthorized occupation of pavements and open spaces by street vendors has

long been a contentious issue, leading to conflicts between vendors, residents,

and authorities. Similarly, the proliferation of illegal encroachments in

markets like Chandni Chowk and Karol Bagh underscores the challenges faced by

municipal authorities in enforcing regulations and maintaining order (NDMC).

4.2. Enforcement Mechanism: municipal policies and interventions

In recent

years, efforts have been made to streamline regulations and improve enforcement

mechanisms. The Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of

Street Vending) Act, 2014, aims to protect the rights of street vendors while

regulating their activities in a manner that ensures public order and safety

(Government of India, 2014). Additionally, initiatives such as the Delhi Street

Vendors Policy and the Smart Cities Mission seek to address the challenges of

informal urbanization and improve the management of public spaces in Delhi

(Delhi Government, 2019).

However, good

governance and top-down approach are proven strategies for on-ground

challenges. Best example of the same was seen in the year 2022 in the very same

region during G20 events. Initially these approaches might seem harsh, but

considering the complexity of the system, they proved to be the best solution

in illegal encroachments, enforcing regulations and control. Ideally a balanced

step by local Deputy Commissioners (DC) from time-to-time is the key to resolve

this scenario.

While

municipal authorities play a critical role in regulating public spaces in

Indian cities like Delhi, challenges remain in effectively enforcing

regulations and balancing competing interests. Addressing these challenges

requires a coordinated approach involving stakeholders from government, civil

society, and the private sector, aimed at promoting inclusive and sustainable

urban development while upholding the rule of law and public welfare.

5. Impact on community’s right to access and enjoy public spaces

The impact of

privatizing markets on the community's right to access and enjoy public spaces

is multidimensional, encompassing social implications, marginalization of

certain groups, and community responses.

5.1. Social implications of privatization

Privatizing

markets often results in a shift in the social dynamics of public spaces.

Traditionally, markets have served as vibrant hubs of social interaction, where

people from diverse backgrounds come together to buy, sell, and engage in

cultural exchange. However, privatization can lead to the commercialization of

these spaces, where profit-driven interests take precedence over community

needs and social functions Varman & Khare (2017). One significant social implication of

privatizing markets is the restriction or control of access to these spaces.

When private entities take ownership or lease public markets, they may impose

entry fees, membership requirements, or restrictive policies that limit who can

enter and use the space. This can exclude marginalized groups, such as

low-income residents or informal vendors, who rely on public markets for their

livelihoods and social interactions Lintelo (2017).

Furthermore,

privatization can contribute to the homogenization of public spaces. Private

developers or businesses may prioritize standardized designs and commercial

interests, resulting in the loss of unique cultural elements and local

character that define public markets Hashmi (n.d.). This can erode the sense of place and

belonging that communities associate with their local markets, leading to a

decline in social cohesion and collective identity.

Figure 4

![Diagram of sense of place proposed by Punter and Montgomery [1].](https://www.granthaalayahpublication.org/journals-html-galley/77_ShodhKosh_1030_files/image017.jpg)

|

Figure 4 Sense of Place Diagram Proposed by Punter and Montgomery Source Research

paper by Dian Kartika Santoso |

5.2. Exclusionary behaviour and marginalization

The

privatization of markets often exacerbates existing inequalities and marginalizes

vulnerable groups within society. Traditional vendors, street hawkers, and

informal traders, who depend on public markets for their livelihoods, are

particularly susceptible to displacement and exclusion Mishra et al. (2023). As private entities assert control

over public spaces, these marginalized groups may face eviction, harassment, or

restrictions on their activities, leading to economic hardship and social

marginalization.

Additionally, the

privatization of markets can deepen socio-economic disparities within

communities. As public spaces become commodified and cater to wealthier

consumers, access to affordable goods and services may be restricted for

low-income residents Mishra et al. (2023). This can exacerbate poverty and

exclusion, perpetuating cycles of inequality and marginalization.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Infographic

Representing Marginalization Concept Source Shuttestock Images |

5.3. Community responses

Communities

affected by the privatization of markets often mobilize and resist these

transformations through collective action and advocacy. Grassroots movements,

community organizations, and civil society groups may campaign for the

protection of public spaces, the rights of marginalized vendors, and the

preservation of cultural heritage Roy & Mandal (2002). These efforts aim to reclaim public

spaces as inclusive and democratic environments that serve the needs of all

members of the community.

Community

responses to privatization may include protests, demonstrations, and legal

challenges aimed at challenging the encroachment of private interests on public

spaces Bhowmik (2003). In some cases, communities have

successfully lobbied for policy changes or municipal interventions to protect

public markets and ensure equitable access for all residents Roy & Mandal (2002).

Narratively, the privatization of markets can have profound social implications, including the restriction of access, marginalization of vulnerable groups, and erosion of community cohesion. Recognizing the importance of public spaces as inclusive and democratic environments, it is essential to promote policies and practices that safeguard their accessibility, diversity, and social functions for the collective benefit of society.

6. Case Study: Delhi

Encroachers

of varying sizes and forms are plentiful. Some individuals encroach on small

portions of public land, sometimes as minuscule as 10-15sqm. However, larger

groups comprising 30-40 or more people simultaneously seize substantial tracts

of public land. This pattern of land usurpation is most evident in city

markets, undermining the intended public nature of these spaces.

These

encroachers are often represented by traders’ associations, and this practice

is widespread across Delhi, spanning from Khari Baoli,

Chandni Chowk, and Sadar Bazar to the upscale neighbourhoods such as Greater

Kailash and even the esteemed Khan Market.

Originally,

the market areas like Chandni Chowk, Chawri bazaar

and Khari Baoli were designed with shopfronts

featuring small platforms and no awnings. However, with the introduction of

railways in the mid-1860s and the availability of steel girders, the residences

above these markets expanded their narrow balconies into terraces supported by

cast-iron pillars creating shaded pathways on ground floor.

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Encroachment

of Footpath in Khari Baoli Market of Delhi Source Author |

Soon, the

sidewalks became too congested for pedestrians, forcing them to walk on roads.

Over time, landmarks like the Jain Mandir, Gauri Shankar Mandir, and Gurdwara

Sis Ganj Sahib at the entrance of Chandni Chowk market lost their unobstructed

pathways. Recently, the Delhi High Court intervened, instructing the Municipal

Corporation of Delhi (MCD) to clear the encroachments during the G20 and U20

events in Delhi. This clearance effort initially showed results, improving

traffic and pedestrian movement for a brief period. However, the situation has

reverted to its usual crowded state with encroachments. Similar issues persist

in markets like Chawri, Bazar Sitaram, and Khari Baoli. Corridors in all markets built in New Delhi from the

1920s to the early 1960s, such as Connaught Place, Sarojini Nagar, Shankar

Market, Bhagat Singh Market, Khan Market, and others, have faced similar

challenges.

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Pedestrian lanes of Sadar Bazaar Source Google Images |

Except for

Connaught Place, all the new markets developed in New Delhi followed the

longstanding practice of shopkeepers encroaching upon spaces intended for

public convenience. The extent of encroachment varies across markets, with

places like Shankar Market and Bhagat Singh Market showing lesser degrees of

encroachment compared to markets such as Khan Market, various Kailash markets,

South Extension, Hauz Khas, Green Park, and numerous others. In Connaught

Circus and Shankar Market, some corridor space remains unclaimed, whereas in

other markets, virtually none is left untouched.

Example, Khan

Market was established in 1951 and for a few years thereafter, there existed a

covered veranda—a corridor—that shielded shoppers from the sun. However, today,

there's no trace of it. By the mid-1960s, most of the corridor had been

occupied by shopkeepers who displayed their merchandise outside their shops,

gradually erecting temporary structures that became permanent, thus eliminating

the corridor altogether. It's believed that the authorities kept their eyes

absorbed systematically flouting the regulations in these markets, especially

Khan market.

Khan Market

has recently gained recognition as one of the most valuable pieces of real

estate globally, but it has long attracted an affluent clientele. Surrounded by

the residences of some of Delhi's wealthiest inhabitants in areas like Golf

Links, Prithviraj Road, Aurangzeb Road, Mansingh Road, and others, as well as

influential figures in what used to be Man Nagar and Shan Nagar, Humayun Road,

Shahjahan Road, and Lodi Estate quarters occupied by senior bureaucrats,

parliamentarians, and high-ranking military personnel, Khan Market has always

been a hub for the elite. Given its prestigious clientele and constant upkeep,

including regular cleaning and maintenance, it's implausible that municipal

authorities and law enforcement could have overlooked encroachments in such a

prominent market frequented by senior diplomats, politicians, and top-tier

administrators.

Nevertheless,

not only were corridors encroached upon, but the market's first floor,

originally designated for residential use only, was gradually and blatantly

converted into commercial spaces. This transformation occurred without the

implementation of fire safety measures, without obtaining necessary permissions

for land use conversion, and without adhering to the extensive bureaucratic

procedures required for establishing eateries or other commercial ventures

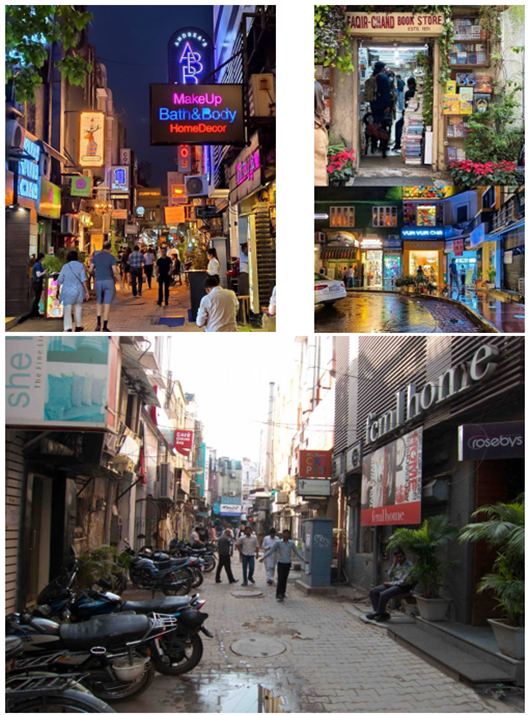

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Khan Market in Present Day Source Google Images

for 1 and 2, Author for Image 3 |

It is

suspected that this transformation occurred with the active involvement of

municipal authorities, given that this market is not an isolated case but

rather reflective of a widespread trend across the city. Similar phenomena have

been observed throughout Delhi. For instance, the South Extension market,

initially a single-story rectangular market divided by the Ring Road, has

significantly expanded over time, absorbing numerous residential properties

that now house exclusive showrooms for international brands or upscale jewellers.

This pattern repeats across almost all markets in the city.

This trend

could be described as a massive-scale encroachment or the emergence of a new

form of public space utilization in public areas. While population growth and

the increasing demand for shops and commercial spaces are contributing factors,

the primary cause of this chaos is the complete absence of comprehensive

planning to accommodate the needs of an ever-expanding city that is straining

at its seams.

7. Conclusion: Reimagining public spaces

7.1. Strategies and recommendations for policy makers and planners

In the wake

of privatization and encroachment of public spaces in Indian markets,

reimagining these vital urban landscapes becomes imperative. Recognizing the

multifaceted challenges posed by the transformation of public spaces into

privatized domains, it is essential to adopt a holistic approach that promotes

inclusivity, community participation, and sustainable urban development. As we

envision the future of Indian markets, policymakers, planners, and community

stakeholders must collaborate to devise innovative strategies and

recommendations that prioritize the publicness of these crucial urban spaces.

One key

strategy for reimagining public spaces post-transformation is the promotion of

mixed-use development. By integrating commercial, residential, and recreational

functions within market areas, planners can create vibrant, multifunctional

spaces that cater to diverse needs and preferences. Mixed-use developments

encourage pedestrian activity, foster social interaction, and contribute to the

vitality of urban neighbourhoods, thereby enhancing the publicness of

marketplaces.

Furthermore,

policymakers can incentivize the adaptive reuse of existing infrastructure and

vacant spaces within markets. By repurposing underutilized buildings and land

parcels, cities can revitalize neglected areas and create new opportunities for

community engagement and economic activity Mehrotra (2018) Adaptive reuse projects can include

initiatives such as pop-up markets, cultural festivals, and art installations,

which activate public spaces and celebrate local identity and heritage Chakraborty (2023)

In addition

to physical interventions, policymakers can leverage technology to enhance the

accessibility and inclusivity of public spaces in Indian markets. Digital

platforms and mobile applications can provide real-time information on market

events, promotions, and amenities, empowering residents to navigate and engage

with their local markets more effectively Varman & Khare (2017). Moreover, smart infrastructure and

sensor technologies can optimize the management of public spaces, improving

safety, efficiency, and sustainability Roy & Mandal (2002).

7.2. Community led initiatives/ participatory planning

Community-led

initiatives also play a crucial role in reimagining public spaces and fostering

a sense of ownership and belonging among residents. Participatory planning

processes, community design workshops, and grassroots organizing efforts enable

local stakeholders to voice their concerns, aspirations, and ideas for

improving their neighbourhoods Lintelo (2017). By empowering communities to actively

participate in the decision-making process, cities can co-create public spaces

that reflect the diverse needs, values, and identities of their inhabitants Mehrotra (2018).

Moreover,

policymakers can support community-led initiatives through funding, technical

assistance, and capacity-building programs. By investing in local

organizations, cooperatives, and social enterprises, cities can catalyse

bottom-up approaches to urban development and promote social innovation and

entrepreneurship in Indian markets Lintelo (2017). Collaborative partnerships between

government agencies, civil society groups, and private sector actors can

harness the collective expertise and resources needed to address complex urban

challenges and build resilient, inclusive, and vibrant communities. Sengupta (2008)

In conclusion, we may infer that reimagining public spaces post-transformation requires a comprehensive and collaborative approach that embraces innovation, inclusivity, and community empowerment. By implementing strategies such as mixed-use development, adaptive reuse, technology integration, and community-led initiatives, policymakers and planners can create dynamic and inclusive urban environments that prioritize the publicness of Indian markets. As we navigate the complexities of urbanization and globalization, it is essential to preserve and enhance the social, cultural, and economic significance of public spaces as shared assets that enrich the lives of all residents.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bhowmik, S. (2003, January). National Policy for Street Vendors. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(16), 1543-1546.

Chakraborty, A. (2023). A Voyager of Life, Searching its Own Meaning!.

Hashmi, S. (n.d.). Rampant Encroachment in Markets is Pushing Out Pedestrians. The Wire.

Kenoyer, J. M. (1998). Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

Lintelo, D. J. (2017). Enrolling a Goddess for Delhi’s Street Vendors: The Micro-Politics of Policy Implementation Shaping Urban (in)Formality. Geoforum, 84, 77-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.06.005

Mehrotra, R. (2018). Inclusive Public Spaces for Informal Livelihoods. Cities Alliance (UNOPS). WIEGO Limited.

Mishra, A., Linge, A. A., Kakde, B.B., & Dhawad, V. (2023). Identification of the Problems and Prospects of Street Vendors, 40, 285-295.

Roy, R., & Mandal, K. (2002, July). Attractiveness of the Indian Market in Comparison to Chinese Market: A Critical Analysis, 6(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0971890720020205

Sengupta, A. (2008). Emergence of Modern Indian Retail: An Historical Perspective. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 36, 689-700. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09590550810890939

TCPO. (2020). Town and Country Planning Organization.

Varman, R., & Khare, A. (2017). Subalterns, Empowerment and the Failed Imagination of Markets. Journal of Marketing Management, 33, 1593-1602. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2017.1403138

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.